In the United States, Mother’s Day—a holiday dedicated to celebrating mothers and maternal bonds—dates to the beginning of the 1900s. Advocates—including Isabella Stewart Gardner’s close friend Julia Ward Howe—had argued for its creation for decades when President Woodrow Wilson finally made the celebration official across the nation in 1914. We do not know what Isabella thought of the holiday when it was established, but we do know she had a long and complex relationship with motherhood—just like many other women.

Isabella’s own experience with becoming a mother started shortly after she and John Lowell Gardner Jr. married in April 1860. After a honeymoon in Washington, D.C., they moved to Boston and started setting up their home in the Back Bay. During this period, we know that the couple struggled with pregnancy loss. Burial records related to the Gardner family tomb at Mount Auburn Cemetery show that Jack Gardner paid for a plot for a stillborn infant who died on September 10, 1860—exactly five months after his and Isabella’s wedding.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

For a nineteenth-century woman, childbearing was a primary responsibility and life goal. Not only was pregnancy loss a personal tragedy but it could be considered a social failing in this era. It is unclear if Isabella became pregnant again during the next two years of her and Jack’s marriage, but there are no records of other births. However, on June 18, 1863, after years of trying, Isabella gave birth to their son: John “Jackie” Lowell Gardner III.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.009945)

The Museum and its Archives have several images of Jackie. One particularly touching photograph shows Isabella posing with her son. In contrast to the other images of her from her early life, in which she appears stiff and awkwardly posed, this image feels candid. A very youthful Isabella—she was only twenty-three and looked even younger—nuzzles her chin and nose behind the shoulder and ear of her son. Jackie stares straight at the camera, perhaps unaware of how clearly she cherishes him.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC1986.1.3)

John Adams Whipple (American, 1822–1891), Isabella Stewart Gardner and her son, John L. “Jackie” Gardner III, 1864. Albumen on paper, 10.1 x 6 cm (4 x 2 3/8 in.)

Tragically for his parents, Jackie died not long after the photo was taken. He had probably contracted a childhood cold that developed into fatal pneumonia; he passed away on March 15, 1865, just a few months shy of his second birthday. Isabella was bereft at the loss of her son.

Losing Jackie marked a decisive shift in Isabella’s life. She likely became pregnant one more time after her son’s death but suffered another miscarriage. After this loss, doctors appear to have made it clear to the Gardners that it would be impossible for them to have children. As a result, Isabella fell into a deep depression. The proposed remedy for this depression—to travel abroad—would ultimately set Gardner on a new path toward a passion for art and the creation of her exceptional museum. A memento from this first trip—a Hanseatic Beaker from Norway—sits in front of an emotional image of Christ carrying the cross in the Titian Room.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The Titian Room, showing the silver beaker purchased by Isabella and Jack Gardner in Norway on their trip following Jackie’s death, in front of the painting Christ Carrying the Cross, by the

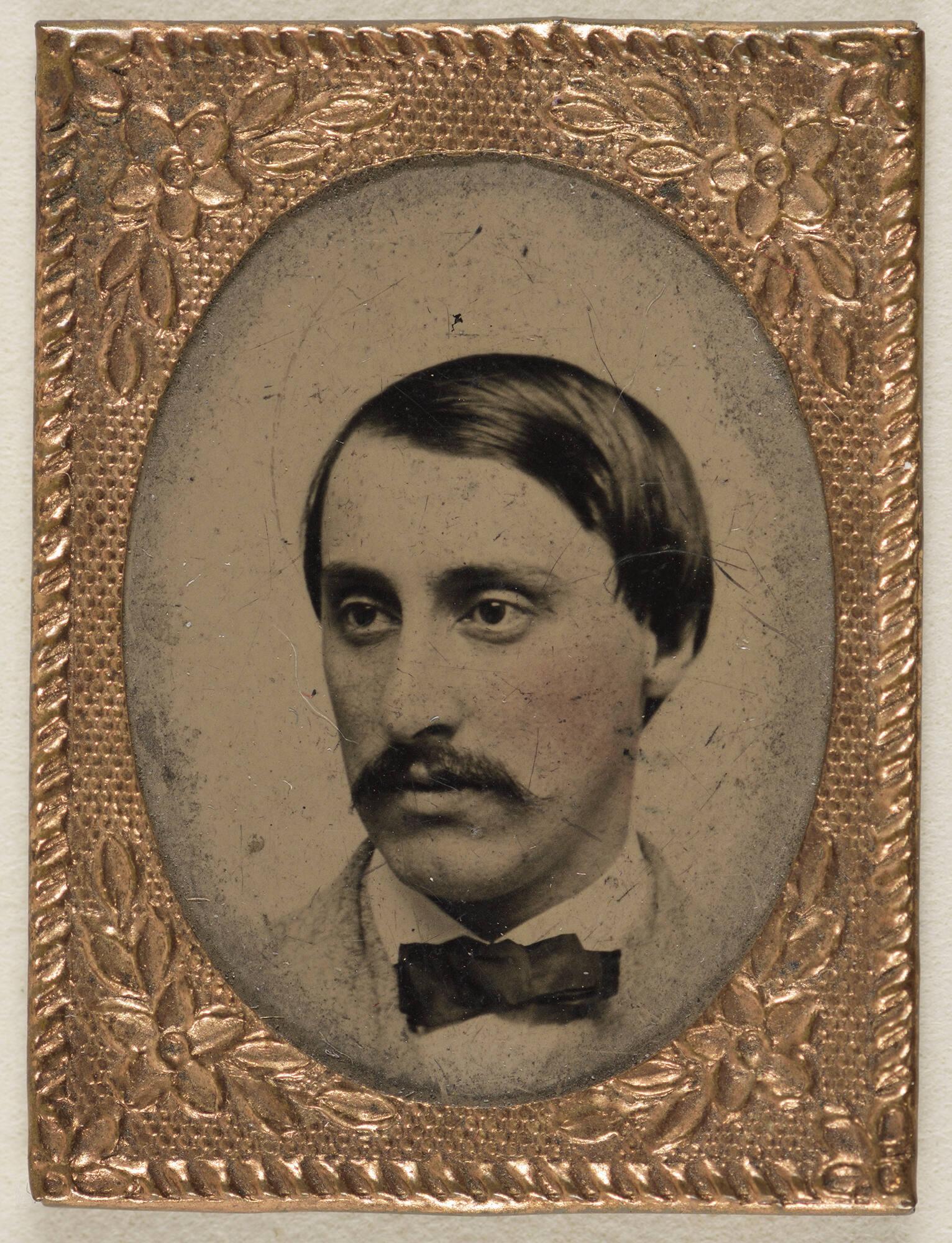

In addition to channeling her considerable energy into the Museum, Gardner went on to be a doting aunt and maternal figure to her orphaned nephews, whom Isabella and Jack adopted after the death of Jack’s brother Joseph in 1875. Joseph Jr. was 14 years old, William Amory 11, and Augustus 9; in many ways, Isabella shaped their lives and interests.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.007616)

Allen & Rowell (active Boston, 1870s-1890s), William Amory Gardner, Joseph Peabody Gardner, and Augustus Peabody Gardner, about 1876. Albumen print

Nonetheless, as her first biographer Morris Carter noted decades later: “For many years the anniversary of Jackie’s death was spent in seclusion,” and in later life, “she never mentioned her child.” In a case in the Little Salon that is often closed, Gardner created what seems to be a private shrine to Jackie and familial loss. A miniature of him appears between pictures of young Jack and Isabella. A photograph of Joseph Peabody Gardner Jr.—one of Gardner’s nephews who took his own life in 1886 at age twenty-five—is also part of this personal memorial.

So, on this Mother’s Day, we consider what the holiday means for those who, like Isabella Stewart Gardner, may have a complex relationship with motherhood. Those for whom it was not all happy memories; for whom it was impossible to become the kind of mother they initially envisioned. She, like many people, may have felt mixed emotions first when Mother’s Day was created, and later when it rolled around each year.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Who’s Laughing in the Gothic Room

Gift at the Gardner

Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life

Read More on the Blog

Greece with William Amory Gardner