The 2020 celebrations of the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution inspired us to ask the question: what did Isabella Stewart Gardner think of a woman’s right to vote? There are no inklings in her surviving correspondence, which is limited, because she asked her friends to destroy her letters. Indeed, one of her favorite French sayings was Pense Moult, Parle Peu, Ecris Rien [Think Much, Speak Little, Write Nothing]—it’s even on a tile in her bathroom.

![Pense Moult, Parle Peu, Ecris Rien [Think Much, Speak Little, Write Nothing] Tile from Isabella’s bathroom in her living quarters on the fourth floor of the Museum](https://www.gardnermuseum.org/sites/default/files/styles/portrait_large/public/2020-10/Tile_Pense_Moult_Unknown_800x948.jpg)

Tile from Isabella’s bathroom in her living quarters on the fourth floor of the Museum

With little in writing, we must look for clues in what Isabella did leave behind—her public museum—where her installations combining art, literature, and ephemera from her contemporaries can be enjoyed, and interpreted, today.

The Blue Room showing Anders Zorn’s Omnibus, the Okakura Case, and the Berenson Case, where memorabilia related to Julia Ward Howe is displayed

Photo: Sean Dungan

One woman Isabella chose to memorialize in her museum was abolitionist and social reform advocate Julia Ward Howe (1819–1910). Julia and Isabella became fast friends when they met shortly after Isabella moved to Boston in 1860. Although Julia was twenty-one years older, the two had a lot in common. Both women were originally from New York, and Julia probably helped introduce Isabella—newly married into the prominent Gardner family—to the nuances of Boston society. They also sadly both lost young children in the early 1860s, and their shared grief surely bonded them.

H.F. Warren (American, active 1860–1865), Julia Ward Howe, about 1865

Isabella displayed this photograph in the Berenson Case, in the Blue Room

When Isabella and her husband Jack moved to 152 Beacon Street in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood, Julia and her family became their neighbors—Julia’s house, a block away from the Gardners’, is now a stop on the Boston Women’s Suffrage Trail. Proximity, a shared love of music, and support for each other's social causes further strengthened their friendship.

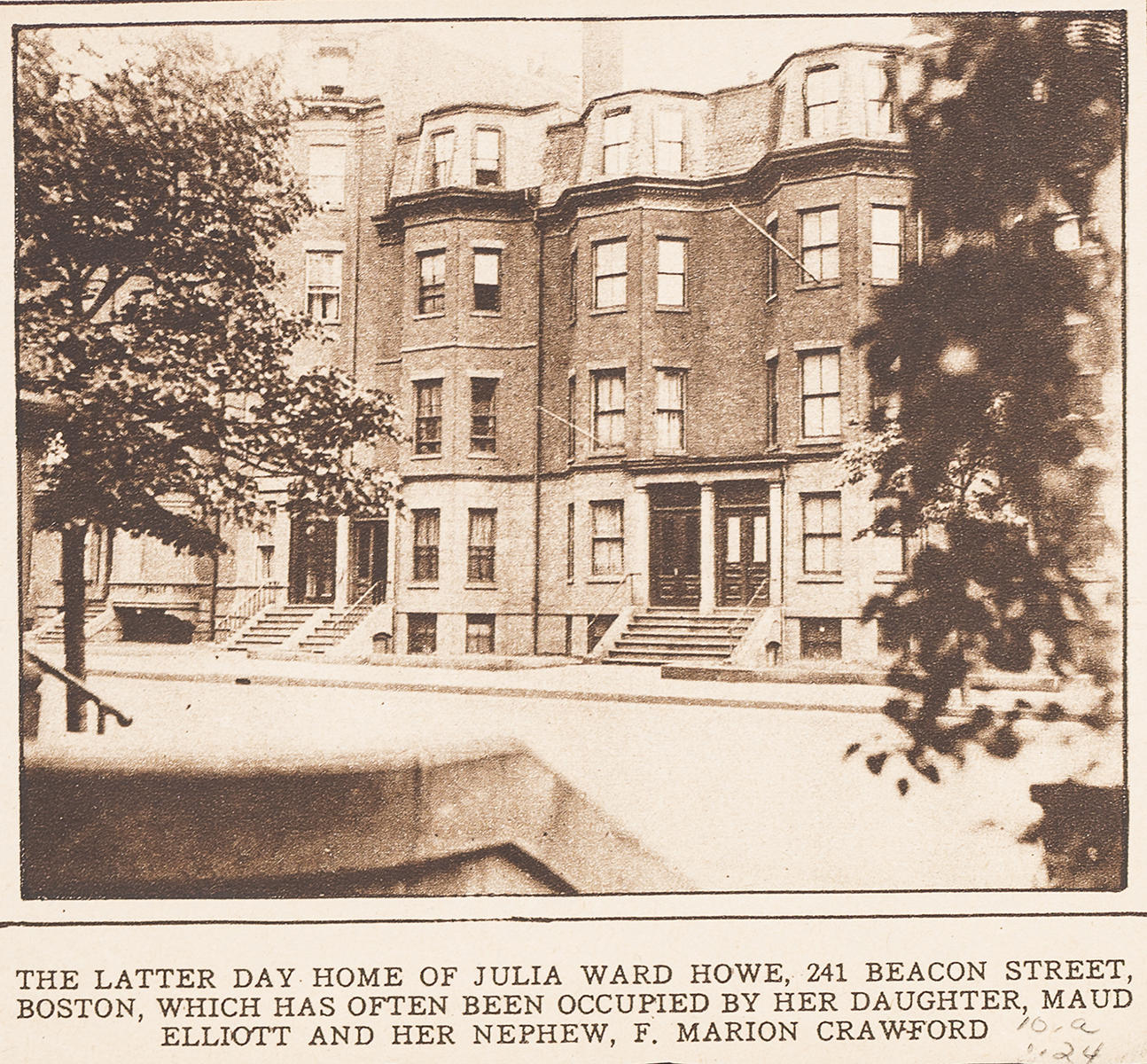

“The Latter Day Home of Julia Ward Howe, 241 Beacon Street, Boston…,” early 20th century

Clipped from a newspaper by Isabella and kept in a book of Julia Ward’s poetry, Passion Flowers, in the Blue Room

A published poet, Julia is best known for writing the pro-Union Civil War anthem, the Battle Hymn of the Republic in 1861. Her fame from the popular song gave Julia a platform on which to champion the political and social issues she passionately supported, including women’s suffrage.

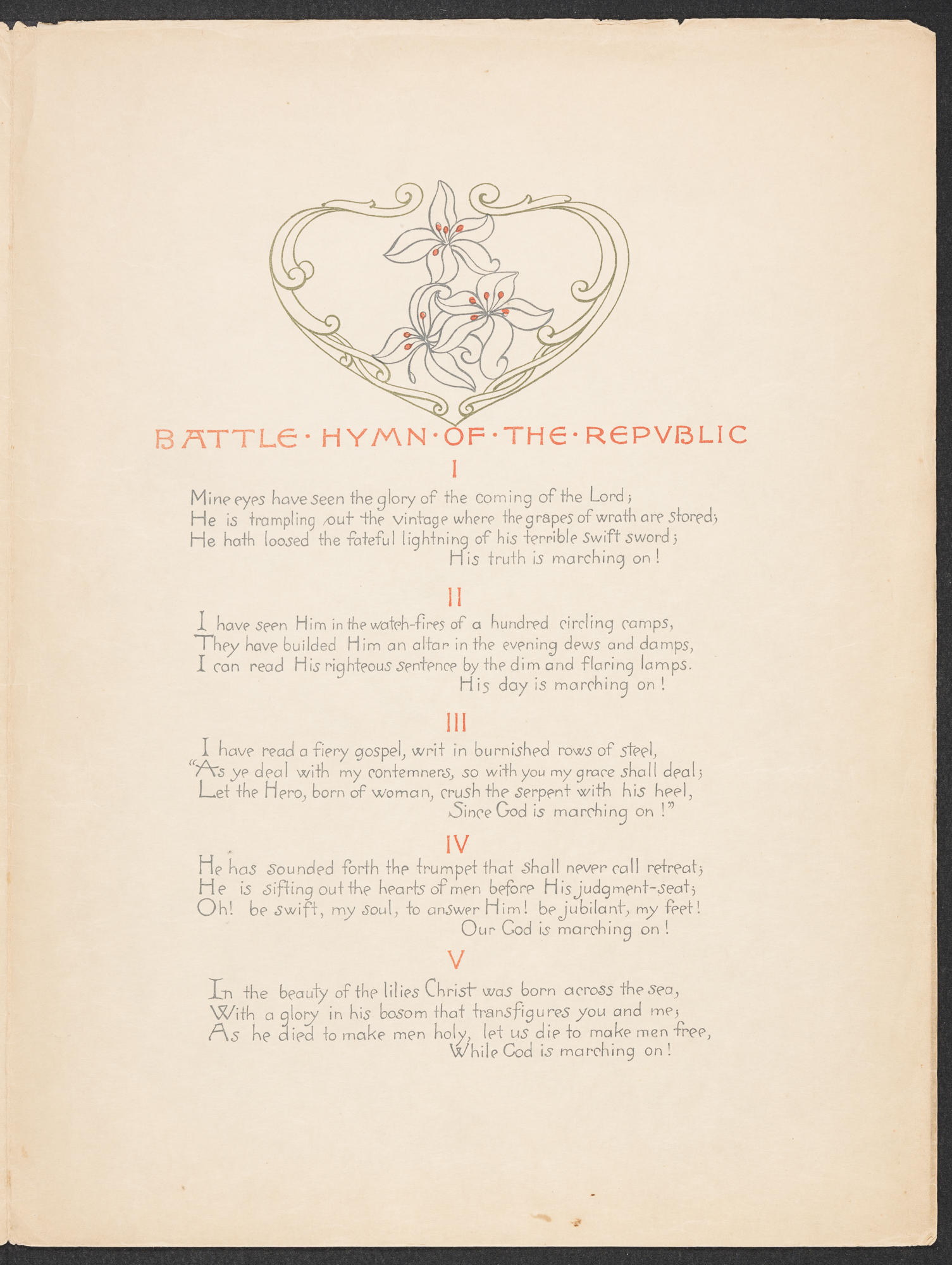

Julia Ward Howe (American, 1819–1910), Battle Hymn of the Republic, 27 May 1889

Published by the New England Women’s Club. Isabella kept this copy in the Vatichino, her personal treasure trove

In 1868, Julia was a founder and the first President of the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA), the first political organization with a goal of securing women’s suffrage. A year after the regional body was formed, she helped organize the national group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), with female and male representatives from twenty-one states. The organization differed from the National Woman Suffrage Association by prioritizing the passing of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution giving Black men—but not women—the right to vote. Many of the members, including Julia, were also active in the abolitionist movement and believed that adding women to the amendment would lead to its defeat. After the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870, the AWSA focused solely on securing the right to vote for women.

“Woman Will Dominate the World, and the Man of the Future Will Follow and Not Lead Her. Remarkable Prophecy by Julia Ward Howe…,” Boston Sunday Post, 10 June 1900

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library

Julia didn’t merely lend her famous name to the cause. She worked with the NEWSA to organize bazaars to raise money and awareness. One of the largest was held at the Boston Music Hall, now the Orpheum Theater, for ten days in December of 1871. The event offered entertainment, and vendors sold everything from knitted blankets to baked goods. She also put her literary skills to good use as a contributor and editor to the women’s right periodical the Woman’s Journal, founded by her friends, the suffragist Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell.

Suffragist Margaret Foley distributing the Woman's Journal in Boston, 1913

Photo: Buck, Courtesy of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000378/

Julia argued for her ideals at the annual women’s suffrage hearings at the Massachusetts State House. When one of the men at a hearing argued against women’s suffrage by stating that most women were indifferent or opposed to it, Julia offered that the suffragists and their opponents may be equal in number, but not in wisdom.*

She [Julia Ward Howe] never wearied of presenting the arguments for suffrage; she often suffered vexation of spirit in refuting those brought against it, but she never refused the battle.

For over 40 years, Julia fought the battle for women’s suffrage, almost half of her long life. She died ten years before the 19th amendment was ratified. On the day of her funeral, the people of Boston hung their flags at half-mast throughout the city, and one hundred thousand school children sang the Battle Hymn of the Republic in her honor. Her casket arrived in Boston by train from her Rhode Island home. Isabella met her deceased friend at the station to accompany her to Mount Auburn Cemetery.†

Isabella lived to see the 19th amendment ratified in Massachusetts in 1919 and 35 other states by 1920, although she was in poor health after suffering her first stroke. There is no direct evidence of Isabella’s interest in the suffrage movement or voting herself, but she did choose to memorialize her dear friend—and her accomplishments—in her museum.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

The Berenson Case in the Blue Room, 2019. Isabella dedicated a display case in the Museum to Bernard Berenson.

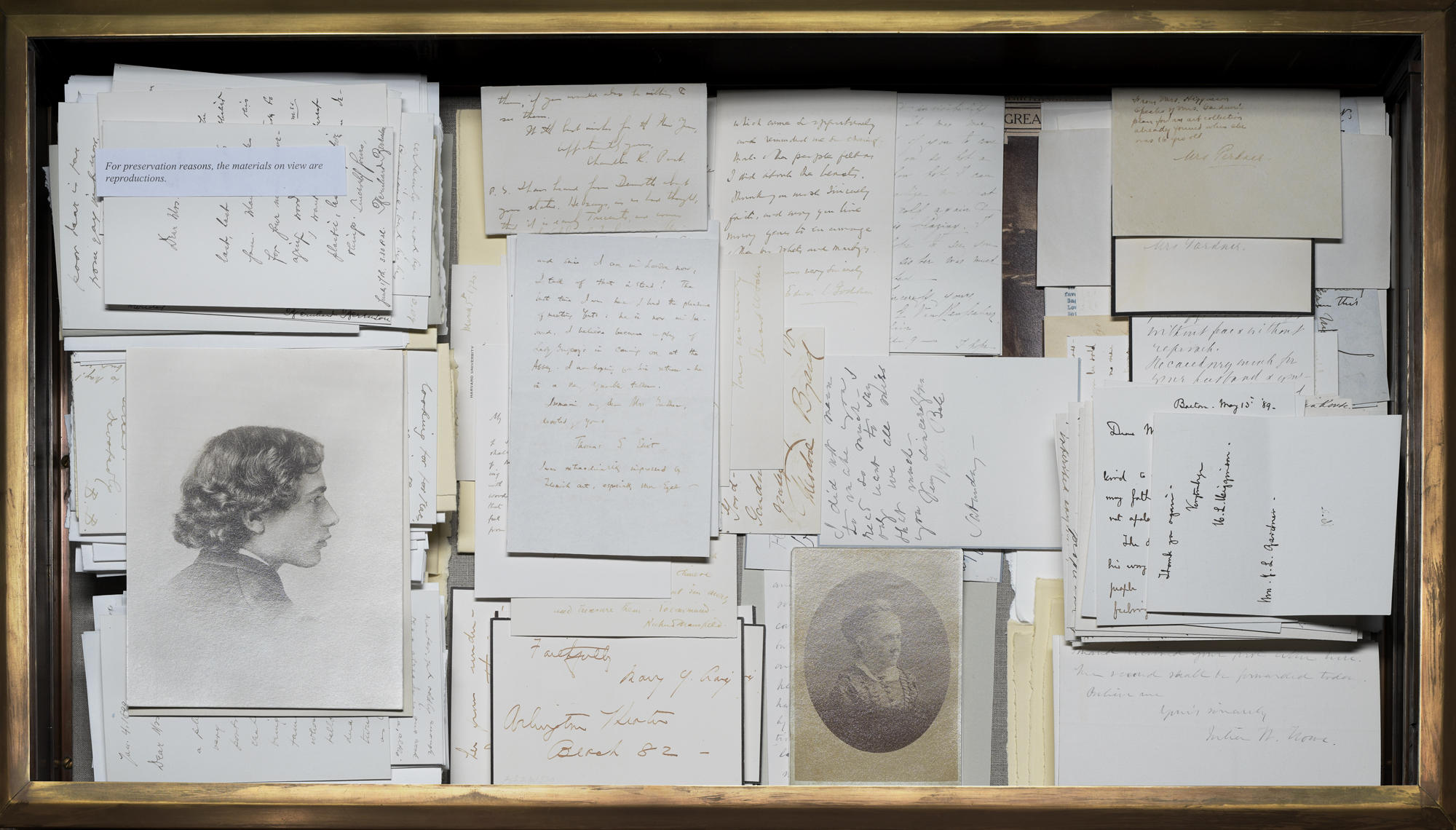

In the Blue Room, Isabella displayed Julia’s letters and photographs in the Berenson Case and her volumes of poetry in a bookcase, where visitors can continue to be inspired by her long fight for equal rights.

Explore the Collection

Julia Ward Howe (American, 1819–1910), Battle Hymn of the Republic, 27 May 1889

Learn about the Cases

Fifteen Hidden Cases

Explore the Collection

Aimé Dupont (Belgium, 1842 - 1900, New York), Ethel Smyth, 1903

*Laura E. Richards and Maude Howe Elliott. Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910), Volume I (Boston, 1915; reprint Atlanta, 1990), p. 367.

†“City and State Honor the Dead: Julia Ward Howe at Rest in Mt Auburn. Throng at Funeral Service In Church of the Disciples. Moving Tribute at Bier by Dr Samuel A. Eliot.” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Boston, Mass, 21 Oct 1910: 1.