As part of the interpretation process for the exhibition Titian: Women, Myth & Power, the Gardner Museum worked with six collaborators who brought their individual perspectives to this exhibition. Each person chose a different Titian painting, crafted a response, and recorded their contribution. Those audio recordings are available both in the exhibition gallery and online. One of our authors, art historian and author Jill Burke, expands on her response below.

Titian (Italian, about 1488–1576), Venus and Adonis, about 1553–1554. Oil on canvas, 186 x 207 cm (73 1/4 x 81 1/2 in.)

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid (P000422) © Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. See it in the special exhibition “Titian: Women, Myth & Power,” August 12, 2021 - January 2, 2022.

I know not to what destiny he is destined

I fear that he is wounded by that wild boar.

I know it—my blood is on its lips

And it seems my heavy heart foretells this.

Alas, my beautiful Adonis lies there languid,

and Death has sown death in his eyes

and now white gillyflowers cover his face

and these bitter tears that I shed

mean that I now cannot see the blood,

but it seems to my eyes just dust.

This excerpt from a sonnet (and I’m afraid this translation can’t reproduce the painstakingly rendered rhythm and rhyme of the Italian original) reminds us that the story of Venus and Adonis has the terrible loss of a loved one at its heart. The north Italian poet, Lucchesia Sbarra (1576–1662), wrote these words in the first decade of the seventeenth century to mourn the death of her son, Giovanni Battista. Sbarra speaks with the voice of Venus, who attempts to prevent her beloved Actaeon from leaving her side to go hunting, as she knows he will die. The last lines change the red blood shed by Actaeon—which in the myth are transformed into red anemones—into white gillyflowers, to represent her son’s pale face. These flowers, now better known as stocks, were commonly cultivated in Renaissance Italy for their scent. They were also (would Sbarra have known this?) used as an herbal remedy in cases of stillbirth.

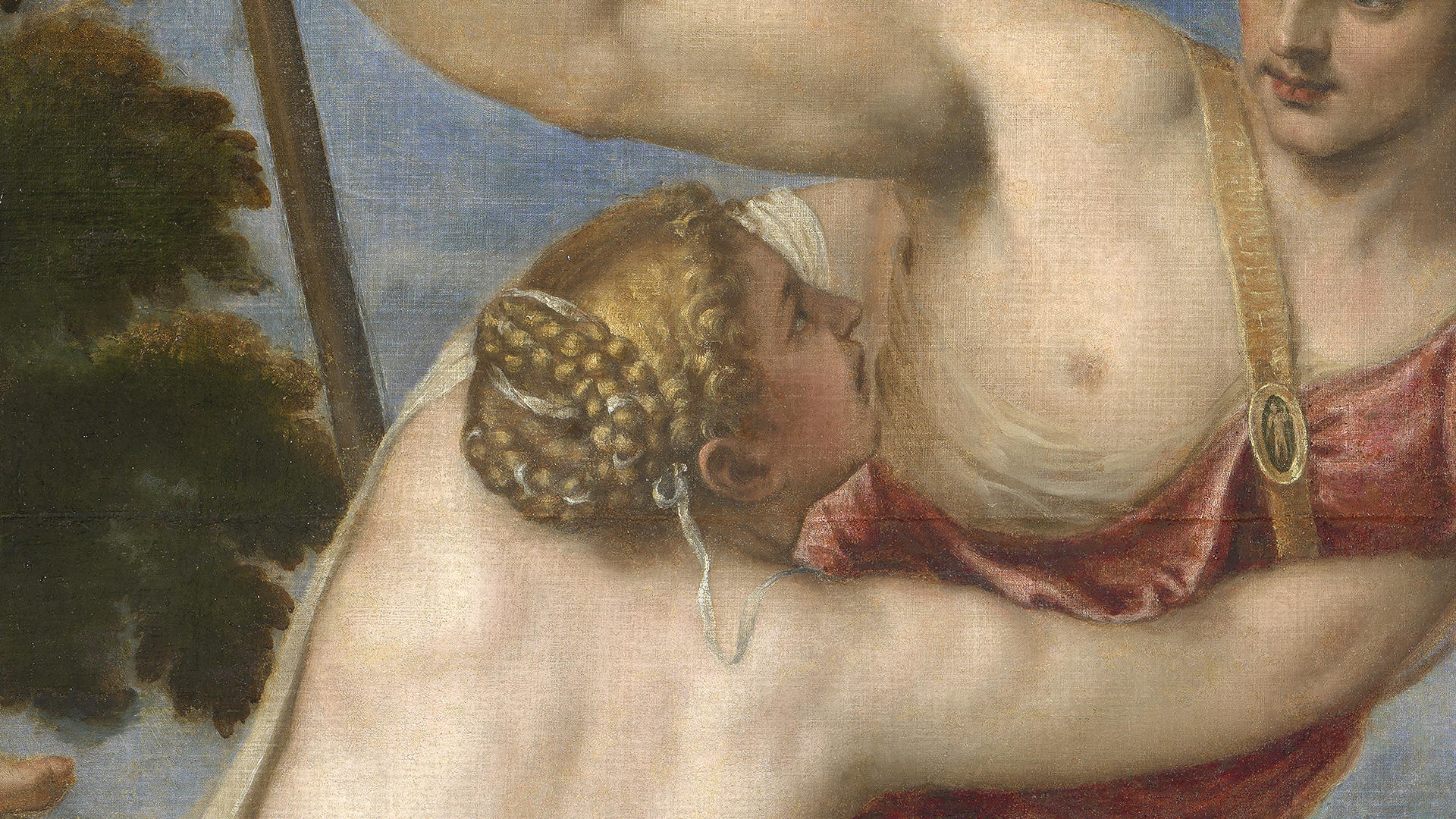

The most famous commentary on Titian’s painting of the same subject is by a male writer, Lodovico Dolce, whose enthusiastic encomium to Venus’s buttocks is much repeated in the art historical literature: ‘I swear to you that you won’t find any man so mean of vision and judgement that he won’t believe Venus to be alive; no one so cooled by age, or so tough of temperament, that on seeing her wouldn’t feel their bodies heating up, melting and their blood stirring in their veins’. It’s not surprising that many interpretations of the Venus and Adonis, and the poesie in general, focus on the sensuousness of Titian’s female figures. Like all good artworks, though, Titian’s works are multifaceted, and Sbarra’s poem can perhaps prompt viewers to notice different aspects of the painting. Venus clings to Adonis, and gazes up at him. A single white ribbon has come loose from her tightly braided hair, and dangles on her shoulder. In a society where women never went outside of the house with their hair unadorned, loose and dishevelled hair signified grief and mourning.

Titian (Italian, about 1488–1576), Venus and Adonis, about 1553–1554, detail showing Venus’s hair

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid (P000422) © Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Although this nod to Venus’s feelings may be understated, Titian increasingly paid more attention to the female victims he portrayed through this series of paintings. In Diana and Calisto, Callisto, forcibly held down by two of Diana’s nymphs has her pregnancy revealed by a third—who by raising her clothing, casts her wretched companion’s face into shadow. Callisto’s hair is loose and messy, her face tilted upwards as if in supplication, her eyes reddened. Most famously in The Rape of Europa, Europa, her face twisted away from us in shadow, struggles on the bull, limbs flailing. The red cloth she grasps seems to be a metaphor for her panic, a hopeless distress signal flapping in the wind.

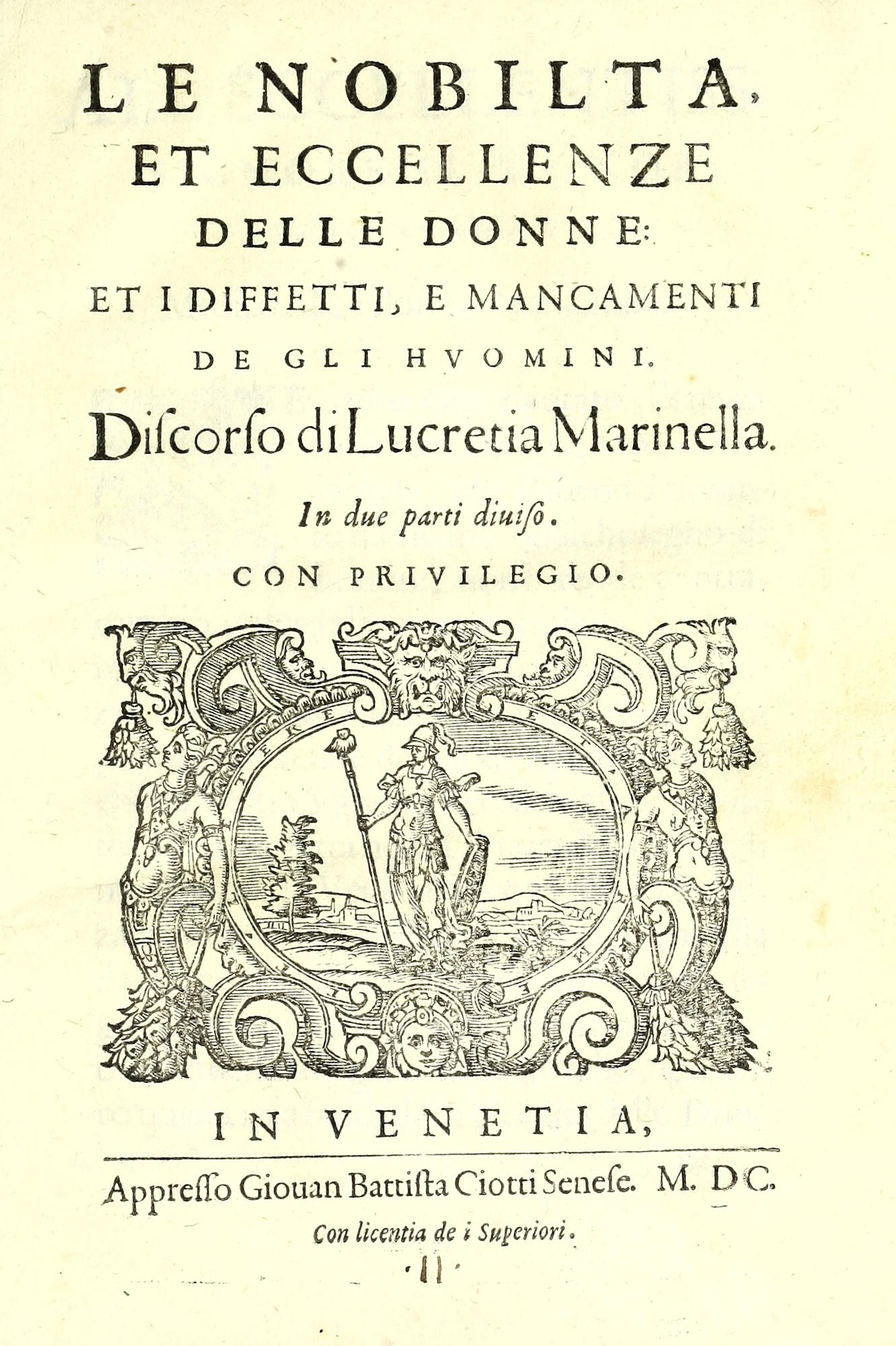

The psychological complexity of his female figures is generally related to Titian’s particular artistic intelligence and emotional acuity—and so it should be. It is also worth saying, however, that he was living in an era where women were increasingly having their voices heard, and arguing that, with the right education, they could be equal to men—an intellectual movement that has been termed ‘Renaissance feminism’. The sixteenth century, particularly in Venice and the small states of Northern Italy, saw a blossoming of women writers who published poetry, plays, and even philosophical dialogues. This perhaps reached its peak in 1600, when two treatises on the merits of women were published—Lucrezia Marinella’s The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men and Moderata Fonte’s The Worth of Women.

Lucrezia Marinella (Venetian, 1571–1653), The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men (title page), 1600.

Getty Research Institute, accessed through archive.org

The sixteenth century was also a time where there were many female rulers and regents, women such as Margaret of Austria, Isabella d’Este, and Mary I of England, the wife of Titian’s patron, Philip II—who would have seen the Venus and Adonis during its brief sojourn in London in 1554. Perhaps Titian’s increased attention to his female characters reflects these broader changes? At any rate, almost five hundred years’ later, it is important to recognize that attending to the words of Renaissance women, like Lucchesia Sbarra, can allow us to see these paintings in a new, sometimes unexpected, light.

*If you would like to find out more about Renaissance women writers, the wonderful ‘Other Voice in Early Modern Europe’ series from Chicago University Press presents and translates many texts by female authors. My account of Lucchesia Sbarra is indebted to the work of Virginia Cox, particularly her translation of some of her poems in Lyric Poetry by Women of the Italian Renaissance and her discussion of women’s writing in The Prodigious Muse: Women’s Writing in Counter-Reformation Italy.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Titian’s <em>Perseus and Andromeda</em> by Johnette Marie Ellis

Attend a Program on September 30, 2021

With Jill Burke, Jenni Sorkin, Mary Reid Kelley, and Patrick Kelley

Buy the Book

Titian’s <em>Rape of Europa</em>