Titian: Women, Myth & Power Gallery Guide

Tiziano Vecellio, called Titian, transformed Western art. Employed by the Holy Roman Emperor, several princes, two popes, and the city of Venice, he forged a peerless international reputation as Europe’s leading portraitist and master of mythological subjects. Titian was as much a legend in the Gilded Age as he was in his own time. In 1896, Isabella Stewart Gardner bought the Rape of Europa, which became the most famous Renaissance artwork in America.

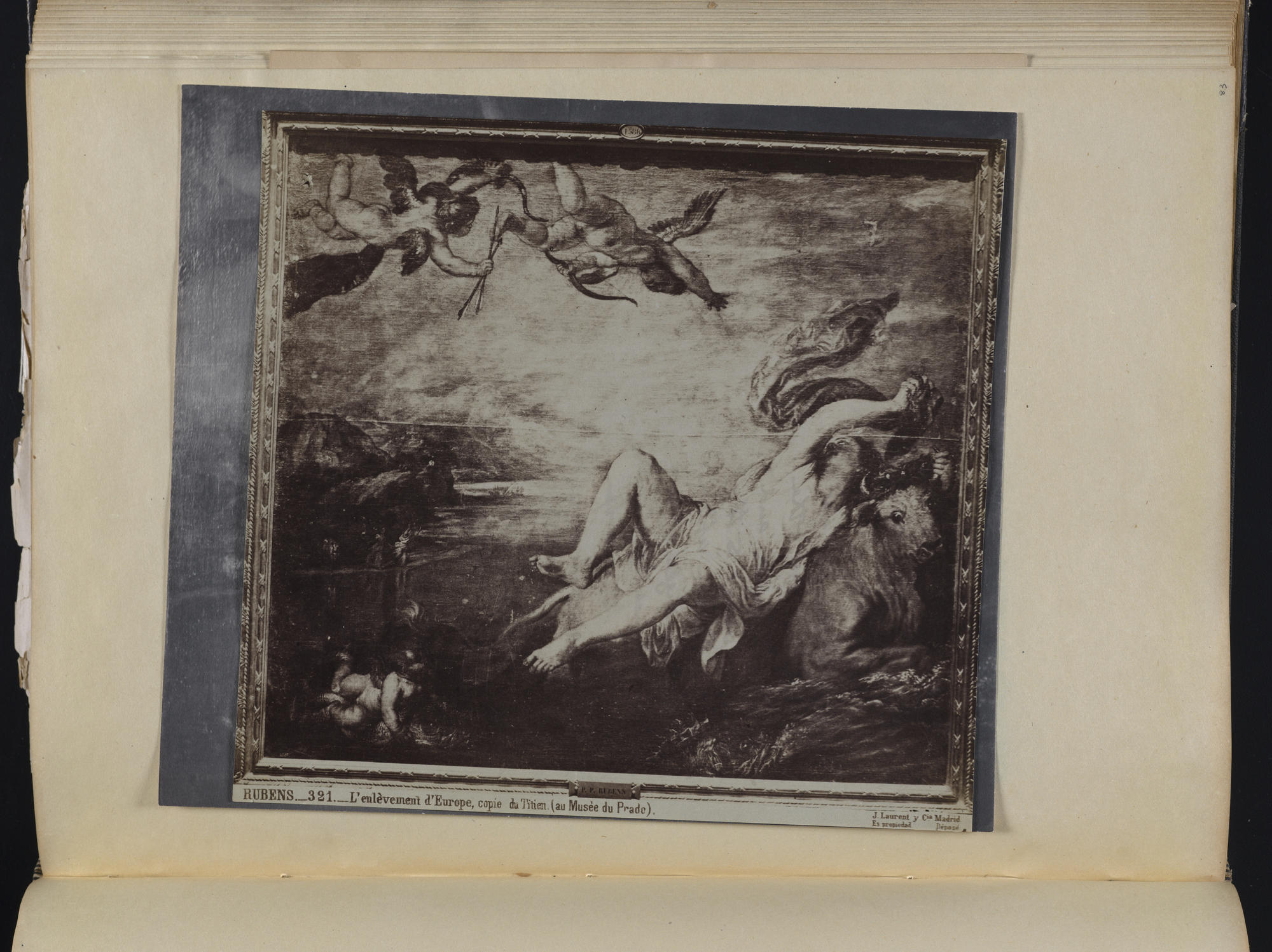

This exhibition brings together Europa with her five companions, reuniting a legendary series of six mythological paintings called the “poesie,” painted poetries, commissioned by King Philip II of Spain. Titian created them for Philip between 1551 and 1562, responding to ancient Roman myths, above all through the poetry of Ovid, in majestic color and with unprecedented originality. Titian’s relationship with Philip was the most productive of his career, and its artistic legacy endures. Inspired by his work, painters of subsequent centuries—including Peter Paul Rubens and Diego Velázquez—transformed Titian into an icon and shaped the future of painting in his wake.

We invite you to consider Titian’s poesie from multiple perspectives, then and now. Portraits of Philip and his older wife, Queen Mary Tudor, help us to imagine their points of view. Scholars and artists share personal insights into individual paintings with audio stops. Newly commissioned responses by the contemporary artists Barbara Kruger (Body Language on the Anne H. Fitzpatrick Façade) and Mary Reid and Patrick Kelley (The Rape of Europa in the Fenway Gallery) engage with questions of power, agency, and sexuality as relevant today as they were in the Renaissance. Together they help us to reconsider Titian for a new era.

Titian: Women, Myth & Power explores themes of sexual assault and violence.

Click here for additional resources

Acquiring Europa

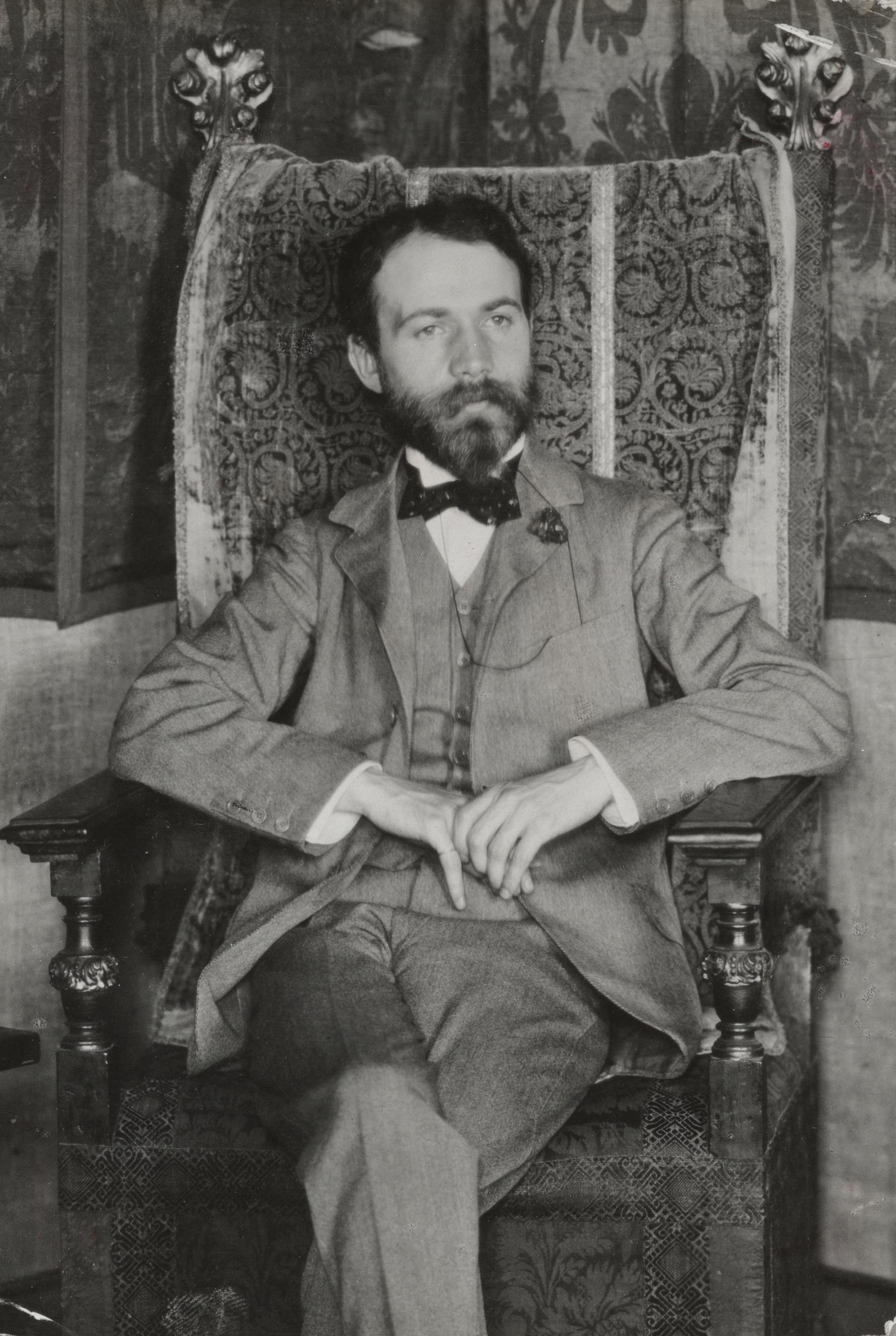

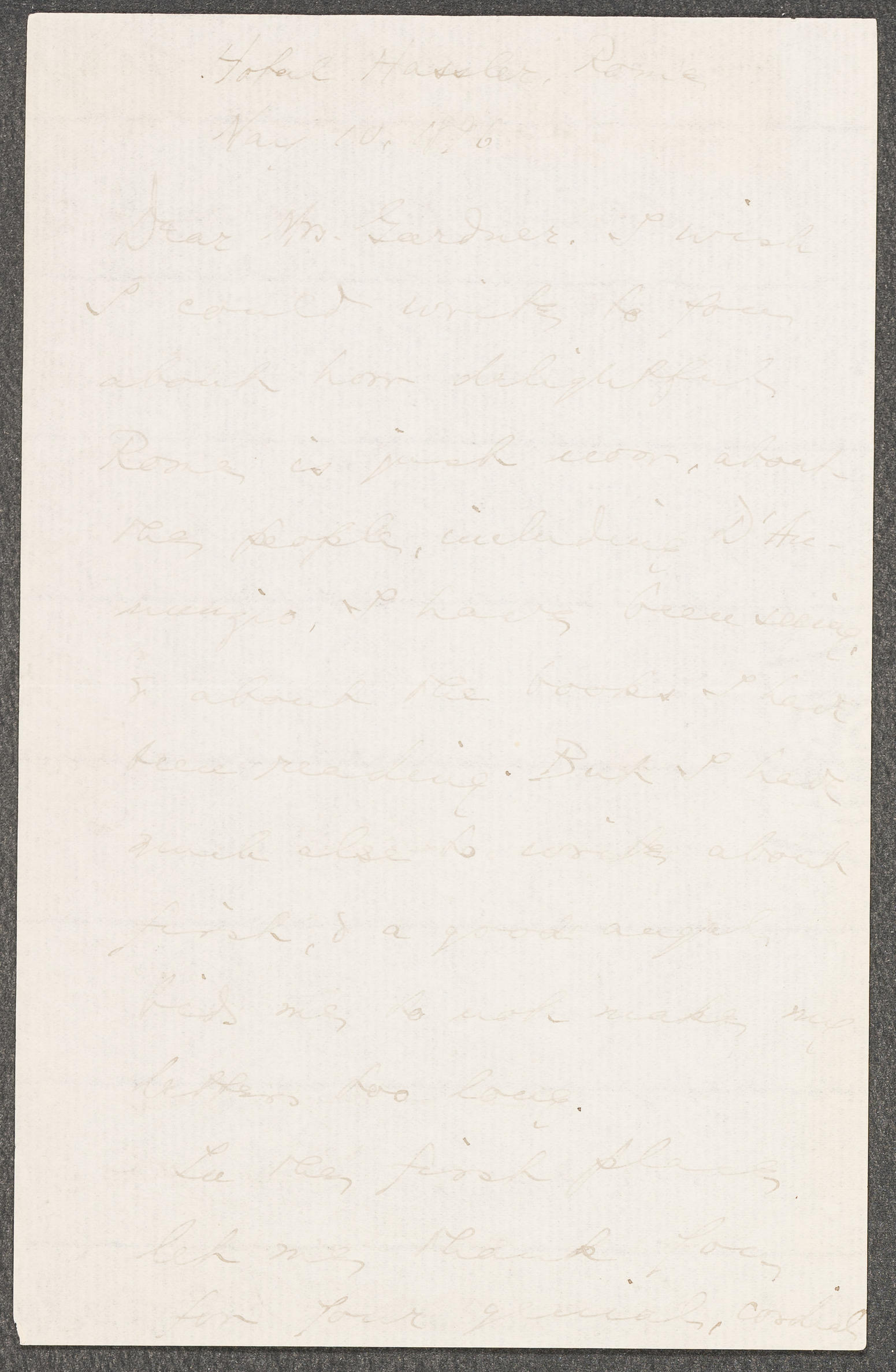

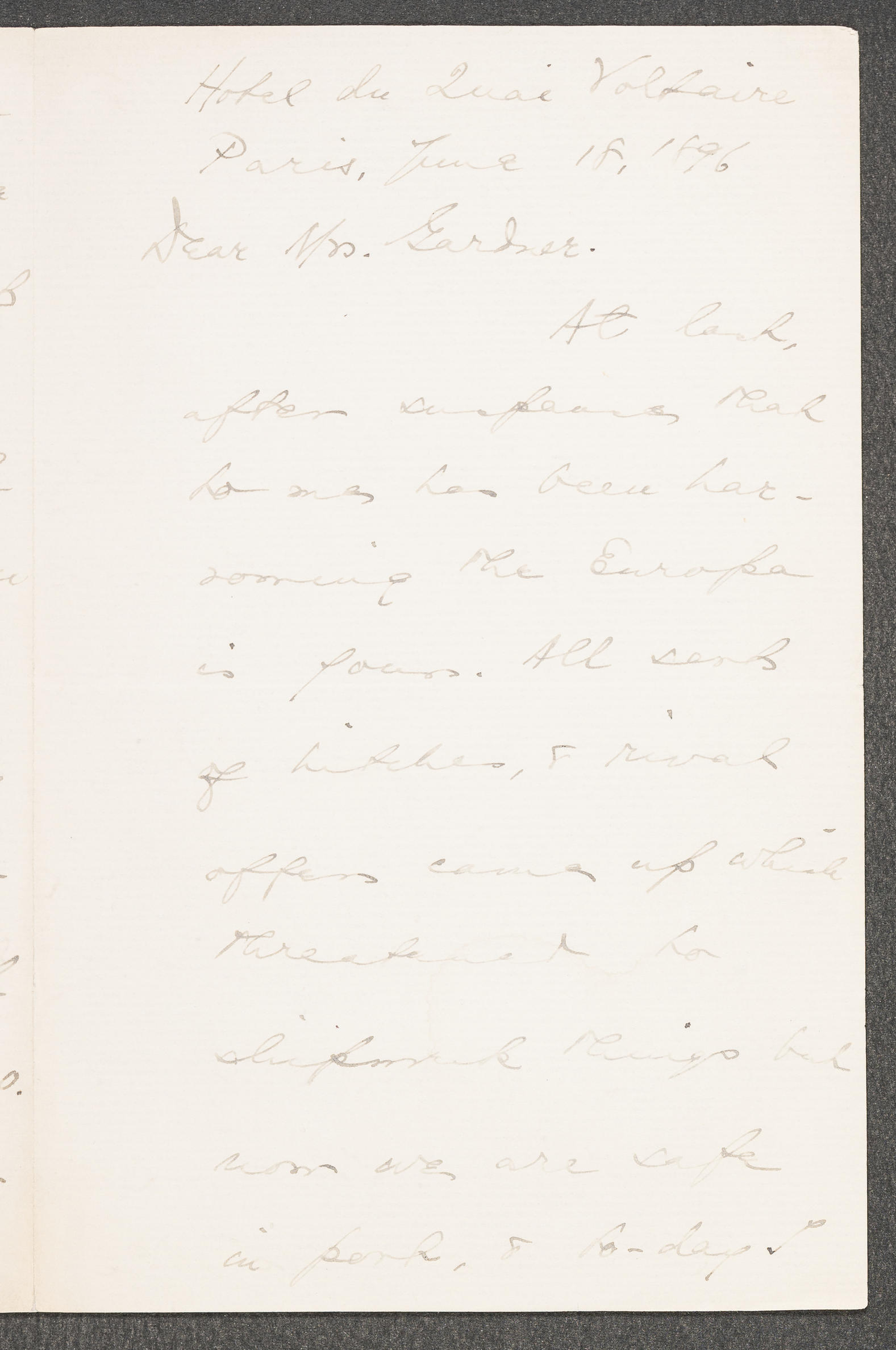

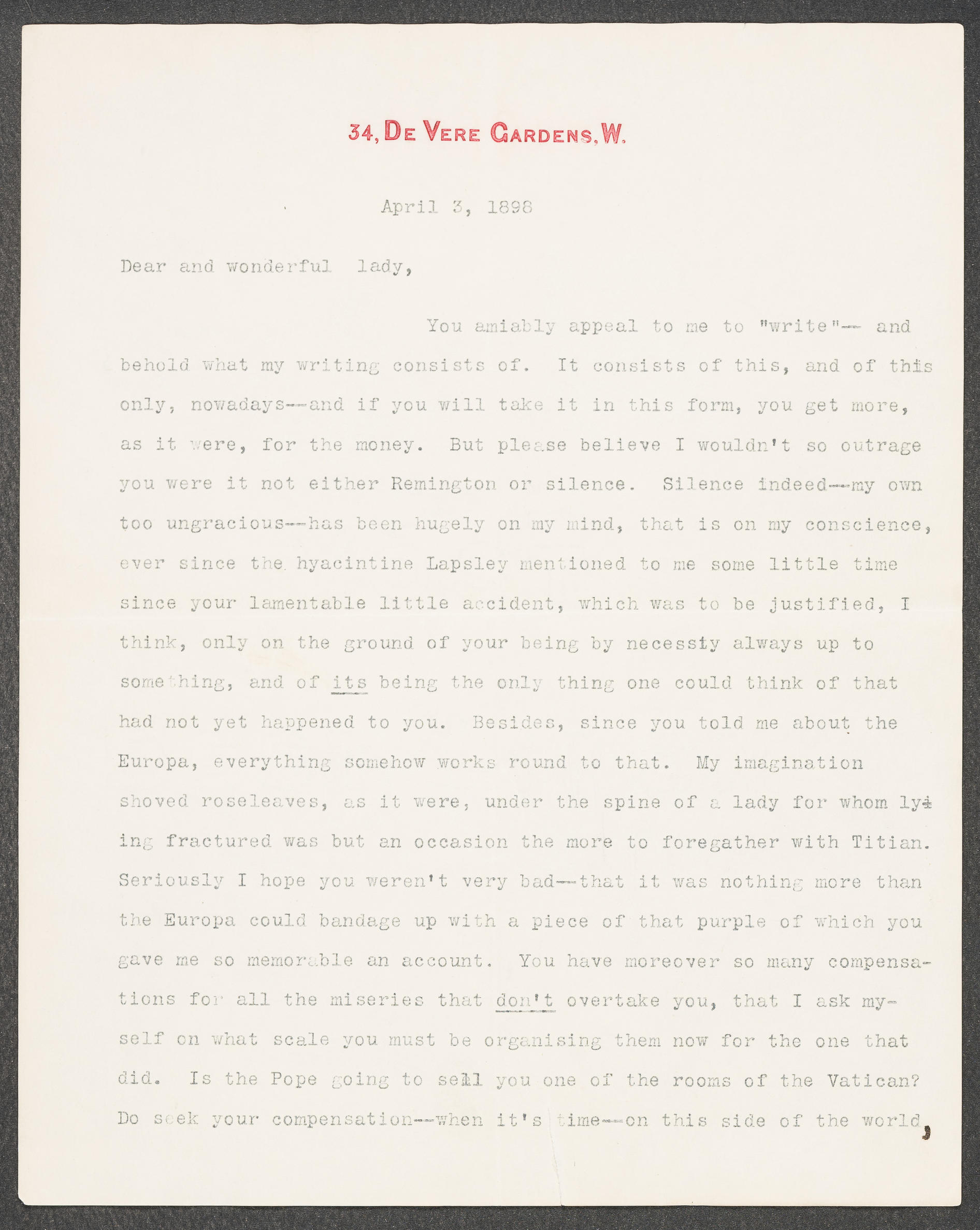

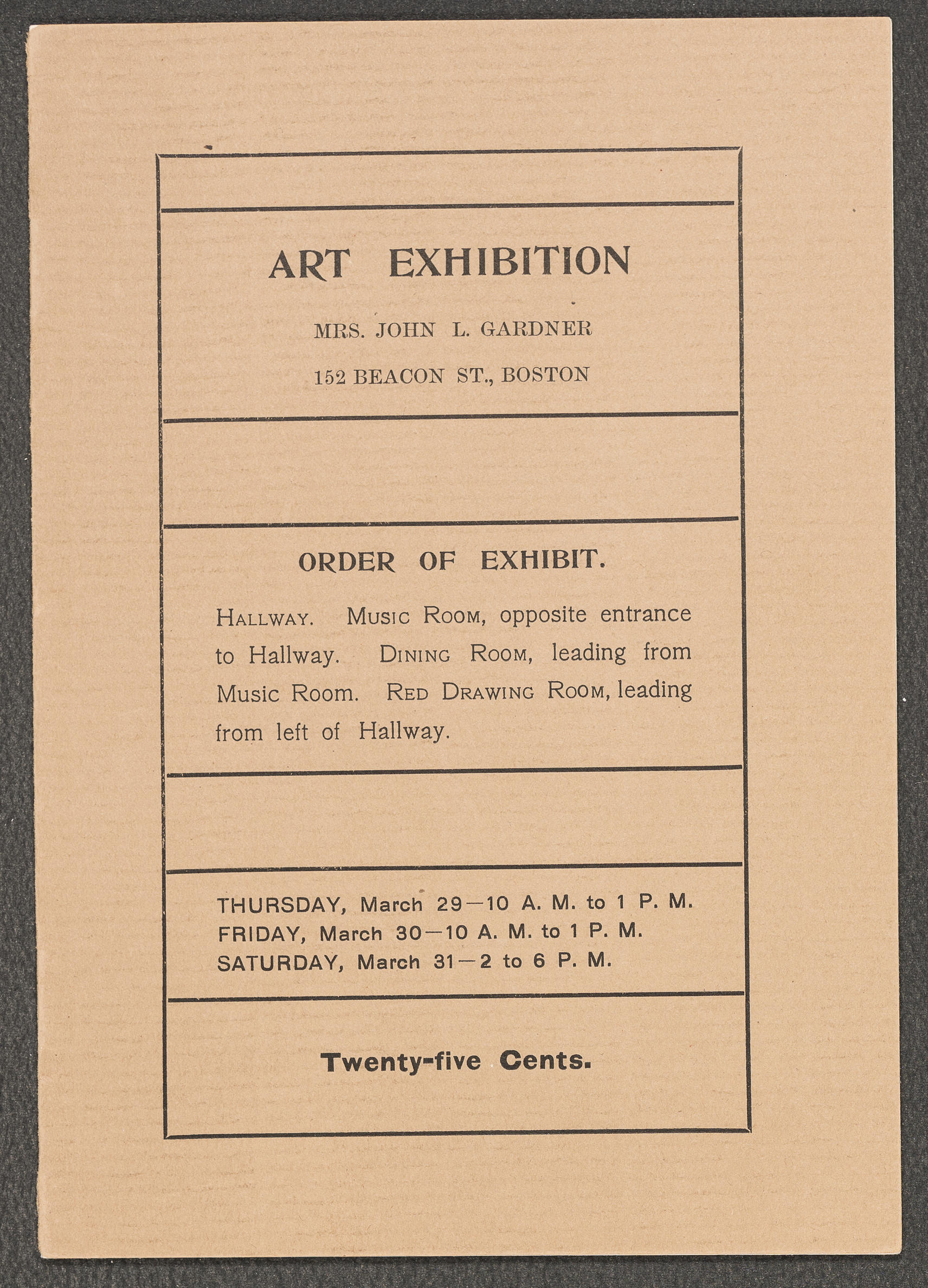

Considered a “mighty poet” by the novelist Henry James, Titian rose to the top of Gilded Age collectors’ shopping lists. In 1896, Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased Titian’s Rape of Europa from an English aristocrat through her close friend, the art dealer Bernard Berenson. The first major painting by Titian acquired in the United States, it became the crown jewel in her collection and a local sensation. Gardner arranged a gallery of her new museum around Europa and named it after the artist. In the Titian Room, she installed Venetian artworks, portraits depicting members of the Habsburg family, and interpretations of the same mythological story by other artists, two of which are displayed nearby.

Display Case

All objects in this case are from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Restoring Titian’s Europa

Titian painted Europa with high quality materials and brilliant colors. Conservators recently undertook the first comprehensive cleaning and analysis of this painting, resulting in the new insights into Titian’s techniques featured in this room.

The Work

Pigments

Titian cleverly envisioned a sky in transition, from clear blue to cloudy gray. Scientific analysis demonstrated that it contains two different blue pigments. Ultramarine delivers the brilliant azure visible on the left. This pigment was extremely stable but also very expensive, based on the mineral lapis lazuli, imported to Venice from present-day Afghanistan. Smalt, an extremely unstable pigment created from ground glass, changes color over time, resulting in a more muted hue. The dark, gray-brown at the right is a result of its decomposition. This area originally would have appeared grayish or silvery blue, appropriate to the wispy clouds.

Composition

Technique

Explore the full exhibition

The lead sponsors of Titian: Women, Myth & Power are Amy and David Abrams and The Richard C. von Hess Foundation

The presenting corporate sponsor is:

This exhibition is supported by the Robert Lehman Foundation, Fredericka and Howard Stevenson, and an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Additional support is provided by an endowment grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Museum receives operating support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Media Sponsor: The Boston Globe.