As part of the interpretation process for the exhibition Titian: Women, Myth & Power, the Gardner Museum worked with six collaborators who brought their individual perspectives to this exhibition. Each person chose a different Titian painting, crafted a response, and recorded their contribution. Those audio recordings are available both in the exhibition gallery and online. One of our authors, art historian Shawon Kinew, expands on her response below.

Titian (Italian, 1488–1576), The Rape of Europa, 1559–1562. Oil on canvas, 178 x 205 cm (70 1/16 x 80 11/16 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P26e1). See it in the special exhibition Titian: Women, Myth & Power through January 2, 2022 or in the Titian Room.

When I wrote for the interpretive project “Reconsidering Titian,” I tried to capture the many different questions that arise for me when I look at Titian’s Rape of Europa. As an art historian and a professor, I find myself relaying facts of its commission, of the longstanding relationship brokered between Philip II, King of Spain, and Titian, the preeminent painter of Europe at this time. It is a relationship that was cinched by the poesie, the paintings that make up the Gardner’s exhibition. But these facts don’t really capture the power of this painting, an equally crucial aspect. It is one we can all see, and, perhaps for those of us brave enough, feel. Of all the poesie on display, The Rape of Europa is the most violent, the most frightening.

Titian (Italian, 1488–1576), The Rape of Europa (detail showing Europa), 1559–1562. Oil on canvas, 178 x 205 cm (70 1/16 x 80 11/16 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P26e1). See it in the special exhibition Titian: Women, Myth & Power through January 2, 2022 or in the Titian Room.

Europa trembles. She holds on to the bull, not because she wants to, not because she has any choice in the matter, but because she would otherwise fall and drown. Painting Europa in this way was a deliberate decision made by Titian: it allows us, the viewer, to empathize with Europa, to identify the terror she feels, and to feel compassion for her. We see the sea monster below her, a creature who embodies the danger of this voyage. We are also witness to the speed at which Jupiter, in his bullish guise, moves, stealing the young woman as he tears across the sea. Titian does this in the white waves he paints beneath Jupiter’s shoulders. The thrashing of the painted waves mirrors the tap-tap-tap of the brush Titian loaded with white and applied across the canvas, a gesture of painterly speed mimicking the speed of Jupiter’s crossing. In this act of being stolen, Europa becomes the mother to Jupiter’s child, the offspring of whom forms the continent of Europe as a cultural entity and the bedrock of “western civilization.”

Titian (Italian, 1488–1576), The Rape of Europa (detail showing the sea monster), 1559–1562. Oil on canvas, 178 x 205 cm (70 1/16 x 80 11/16 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P26e1). See it in the special exhibition Titian: Women, Myth & Power through January 2, 2022 or in the Titian Room.

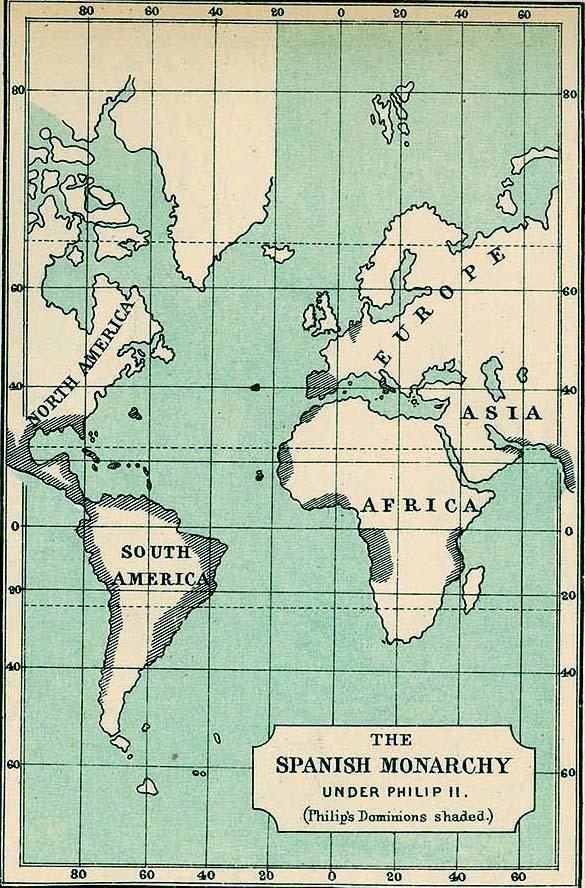

At the time of Titian’s painting of The Rape of Europa, its patron, Philip II, was on the precipice of doing something no ruler had done before: expanding his empire to encompass the globe. The Spanish Empire would extend far beyond Europe to the Americas and to Asia (the Philippines take their name from the Spanish King). The lasting effects of Philip II’s empire are felt in American history, too: many of the southern states in the present-day United States were once Spanish territory. The legacy of Philip II is one of the emergence of a global economy, one accomplished through colonialism, genocide, and slavery.

C. Colbeck (editor), Map of the Spanish Monarchy under Philip II from The Public Schools Historical Atlas, 1905

University of Texas at Austin

While Titian most certainly did not intend this painting to speak to the impending violence of empire, or to provide a coded critique, he did intend his painting to speak to Philip II’s power, a power that was territorial, wrought of conquest and violence. Philip, king of this empire, is like Jupiter, the king of the Olympian gods.

The story of a woman stolen from her land and forced to make a new life is one that should be familiar to us. For those of us who make our home in the shadows of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s palazzo, we are on the land of Indigenous Massachusett people, their ancestors displaced from their traditional land, their ancestors killed in the process. We might also see in Europa an echo of slavery, of ancestors who crossed the Atlantic and in the process were enslaved.

Tribal territories of Southern New England tribes about 1600

Nikater; adapted to English by Hydrargyrum, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Looking at this painting, there is often a troubling realization, one that confuses and confounds our twenty-first-century eyes. How does Europa fit among the erotic Danaë and Venus and Adonis? Does the painting glorify violence? Flatter an undeserving king? For this reason my students often ask, is this painting “bad”?

Gardner, upon receipt of this painting in 1896, wrote of her breathlessness, “the orgy” of “drinking [her]self drunk with Europa.” Sex and sexuality, I believe, have always been a part of how this painting was received. Was it simply having Titian’s painting in her possession, a drunken orgy of the eyes, that brought Isabella pleasure? Was it her conquest and possession of one of Titian’s paintings intended for a king? Or did Isabella find pleasure in its subject, in Europa’s pain?

Thomas E. Marr (Canadian-American, 1849–1910, photographer), Titian’s Rape of Europa installed in Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Back Bay residence, 1900

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (Marr2062)

A painting’s power is in what I call its “shimmering” quality. Europa flickers back and forth among seemingly contradictory elements—the violence depicted and the beauty of seeing a painting by Titian. Europa's distress exists alongside the marvel of glowing bodies, of lapis skies, of dabs of thick paint Titian applied in the 1560s that reach us, direct and unimpeded, in 2021. Titian brokers an encounter in The Rape of Europa with a metaphor embedded in the painting. We, the viewers, like Europa, are taken away. Titian carries us on a journey on his back, and it is one that is emotional and painful, rendered poetically.

Survivors didn’t have choices in what happened to them or their ancestors. I believe we must allow ourselves to feel the fullness of our emotions—in the words of another poet: “let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.” This line to me does not suggest suffering is necessary for beauty to exist. There is no “silver lining” to the inexcusable acts that many of us must bear. It is however within the constellation of beauty and terror that he writes, “go to the limits of your longing.” Europa, in the midst of the unbearable, asks, What are yours?

The Rape of Europa is the most important European painting to find its home in Boston. For me, it’s really a meditation on the continent of Europe and its place in America.

I often wonder what does it mean for this painting to be here?

Since 1896, Europa has called this place, the fens of Boston, her home: where the Atlantic Ocean crashes into the continent of North America. This marshy, sacred land of the indigenous Massachusett people.

This painting moves me because Titian paints this mythic story as a private cataclysm with tremendous consequences. It is a trembling earthquake of a picture.

In the painting we see Europa is carried away, stolen by the king of the gods, Jupiter, a journey that sees her moving across the Mediterranean Sea.

The woman Titian paints is scared as she looks back toward her friends, toward the shore, to the site of the encounter, where she was tricked by a friendly bull, one who coaxed her into taking a ride, one she even crowned with flowers before she realized who he was.

Europa, in white, quivers like a mayflower on the hawthorn branch. Titian rhymes the figure of this terrified woman, waving a red sail in the wind, with a sailing ship, in the far distance, directly behind her.

She is a type of vessel too, Titian seems to say, and this is the story of a voyage, a maritime crossing, just as much as it is an origin myth, one of transformations.

Philip II, ruler of a global empire, saw himself reflected in Jupiter’s conquests.

Seizing women is like seizing land and people, and the children born of these encounters extend the might of the ruler or they bear the consequences.

So I often wonder what does it mean for this picture, for Europa, to be in America?

This painting of empire is at home here.

It is about the terrifying idea of being carried away, of being stolen, and of a life spent looking back to the shore.

It’s a painting of life or death, of holding on to the bull’s horn because the only other option is slipping beneath the waves and succumbing to the monster lurking beneath.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

There is You: Titian’s <em>Diana and Callisto</em>

Read More on the Blog

Attending to Women in Titian’s Mythologies

Read More on the Blog

Titian’s <em>Perseus and Andromeda</em>