In a recent post for Inside the Collection, Professor Jill Burke invites us to look anew at the Gardner’s Titian exhibition, “Titian: Women, Myth & Power,” through the lens of one Renaissance woman writer, the inventive and relatively unknown poet Lucchesia Sbarra. Another woman whose writing merits attention—and who is intimately connected with the collection—is the great Vittoria Colonna (1490–1547).

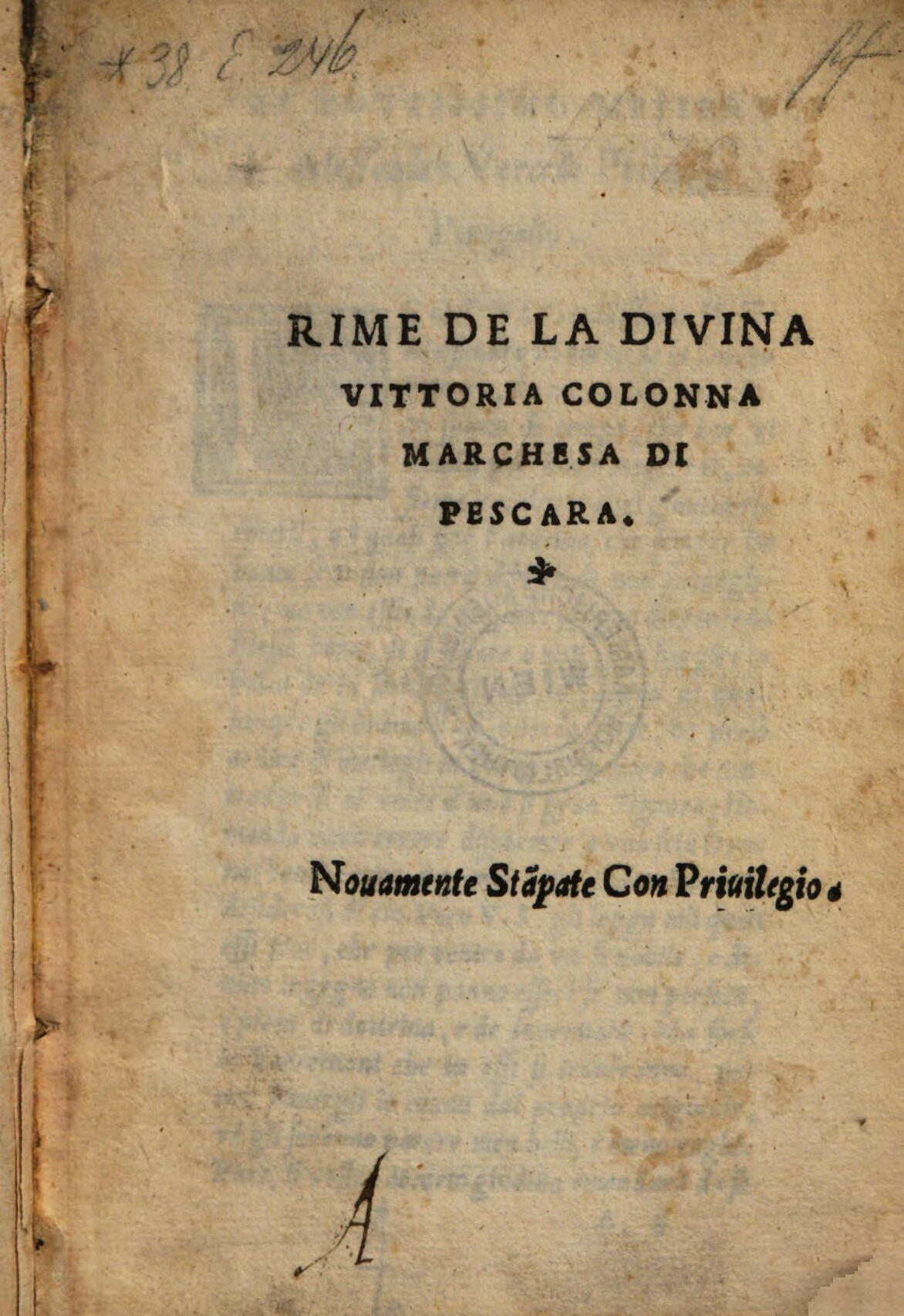

The first woman to have a volume of poetry printed under her own name in her lifetime, she is one of the canonical figures of Italian literature. Colonna was renowned for both her poetry and her social connectedness, the latter best represented by her intimate creative-spiritual rapprochement with Michelangelo. Beyond this friendship, she engaged with a number of other important artists, including Titian, of whom she was a patron.

Sebastiano del Piombo (Italian, 1485–1547), Vittoria Colonna, about 1520–25. Oil on panel, 96 x 72 cm (37 ¾ x 28 ⅜ in.). Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In her love poetry for her deceased husband—the Marquis of Pescara, Ferrante Francesco d’Avalos, a war hero who died in 1525—Colonna wrote several poems employing the same figures from Ovidian myth as Titian did in the poesie currently on display in the Gardner. In one madrigal (A2:52), she pledges not to allow her eyes to settle on any new object of desire, thus “escaping Actaeon’s error” (fuggendo d’Atteon l’errore) when he spied Diana. In the opening line of another poem (A1:25), Colonna recalls the myths of both Europa and Danaë (as well as Leda): “If as gold, as a swan, or as a bull, high Jupiter / was transformed …” (Se in oro, in cigno, in tauro il sommo Giove / converso fu …). In this sonnet, Colonna challenges Love to transport her to heaven, claiming that such a celestial reunion with her husband would be a “greater miracle” (maggior miracol) than Jupiter’s metamorphic conquests on earth.

Colonna’s rime vedovili (“poems of widowhood”) are what first brought her celebrity. But about a decade after her husband’s death, Colonna—an active participant in Italy’s religious Reform movement in the 1530s and 40s —began to focus instead on spiritual matters. Her new religious lyrics maintained the same basic form and lexicon of her love poetry, modeled after the celebrated amorous verse of Petrarch. However, she redirected her love heavenward, writing to or about Christ, Mary, God, and a host of other religious topics. So masterful and moving were these poems that they inspired a new genre of poetry, which was much imitated in subsequent decades.

This devotional and artistic fervor is what caught the attention of Michelangelo. In the intimate friendship that ensued, they created important works of art for each other: she, a handwritten collection of her religious verse; he, a series of drawings, including the Pietà now in the Gardner collection. Both Colonna’s poetry and Michelangelo’s drawings were much admired not only by literati, but by the broader faithful, who copied and repurposed these objects for popular liturgical use.

Another of Colonna’s important contributions to the artistic-religious world was a commission she made to Titian. In 1531, using Duke Federico Gonzaga of Mantua as an intermediary, Colonna requested a painting of Mary Magdalene, a figure who appears frequently in her spiritual poetry. The request was for a large portrait, with a Magdalene both “tearful” and “beautiful.” Precise identification of the painting has eluded art historians, but it may be the Penitent Magdalene today held in Florence’s Pitti Palace. The subject may seem unchastely voluptuous to the modern eye—the "impressive buttocks” of the artist’s Venus and Adonis have nothing on the concealed-yet-revealed curves of this Magdalene. Yet the figure may to the contrary be indicative of surprising characteristics of early modern worship, where devotion and desire were often happy bedfellows (as Colonna’s own poetry not infrequently reveals).

Titian (Italian, 1488–1576), Penitent Magdalene, 1533. Oil on panel, 84 x 69 cm (33 x 27 in.)

Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence

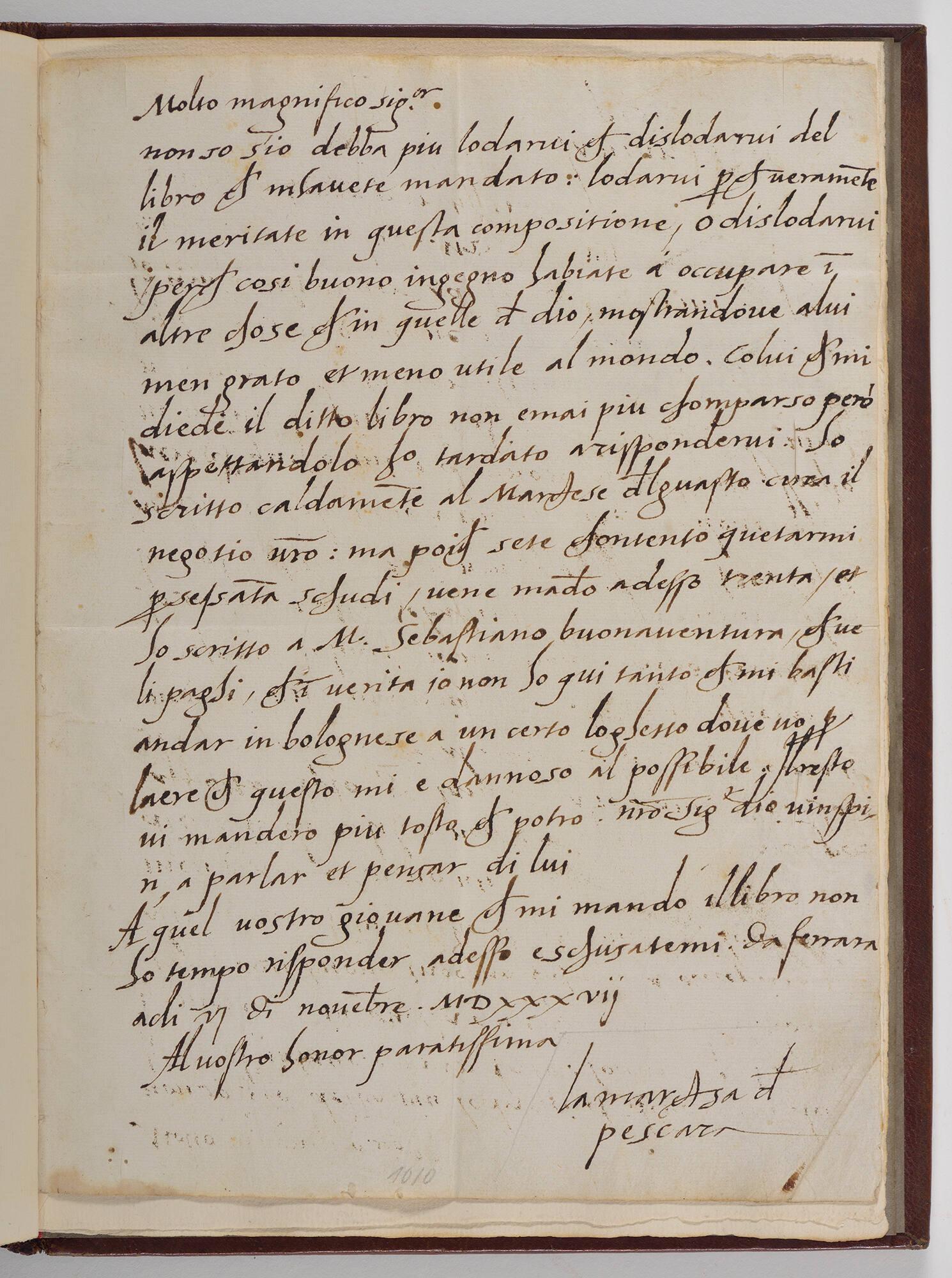

Colonna was an innovator whose impact on writers, artists, and worshippers across the centuries is still being unearthed. Among the many cultural icons influenced by Colonna, we can count Isabella Stewart Gardner herself. She acquired not only the Pietà, but also an oft-cited letter from Colonna to the prominent writer Pietro Aretino, dated to 1537, urging him to turn his writing to religious matters. Several parallels emerge between Gardner and Colonna, both in terms of their private lives (both desired to be mothers but remained childless; both were widows) and as pioneering women of the creative world.

Vittoria Colonna (Italian, about 1490 - 1547), Letter to Pietro Aretino, 6 November 1537. Ink on paper, 30.3 x 22.2 x 1.2 cm (11 15/16 x 8 3/4 x 1/2 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (2.b.3.2). Isabella displayed this letter in the Dante Case in the Long Gallery.

One of the great strengths of the Gardner’s Titian exhibition is the manner in which it has foregrounded women’s experiences, from highlighting the role in the Titian commission of Mary Tudor, wife of the patron of the poesie, to bringing in new work by artists Mary Reid Kelley and Barbara Kruger. Colonna—a woman whose power is interwoven not only with the temporary show, but with the Gardner Museum’s permanent collection—is certainly among the voices with much to tell us.

*To learn more about Colonna, read Ramie Targoff’s engaging biography, Renaissance Woman: The Life of Vittoria Colonna. My discussion of Colonna’s impact draws on contributions from the new volume Vittoria Colonna: Poetry, Religion, Art, Impact, edited by Virginia Cox and myself. For topics mentioned here, see especially the introduction by Virginia Cox on Colonna’s influence; the essays by Abigail Brundin and Jessica Maratsos on Colonna and Michelangelo in popular religious worship; and the contributions by Dennis Geronimus and Christopher Nygren on Colonna’s interactions with Titian and other artists.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Attending to Women in Titian’s Mythologies

Explore the Collection

Michelangelo (Italian, 1475–1564), <em>Pietà</em>, 1540

Explore the Exhibition

Titian: Women, Myth & Power