BOSTON NEIGHBORS: MARGARET AND ISABELLA

Born in 1867, Boston-born composer Margaret Ruthven Lang (1867–1972) had a vivid musical upbringing. Her father, Benjamin Johnson Lang (1837–1909), was a close friend of Isabella’s and an important musical figure in Boston. (He famously conducted both the world premiere of Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto and the American premiere of the concert version of Wagner’s Parsifal). The Langs actually knew the Wagner family well—Margaret would later recall attending concerts with their daughter Isolde. Margaret studied piano and composition with her father, who introduced her to Isabella.

Hampsong Foundation

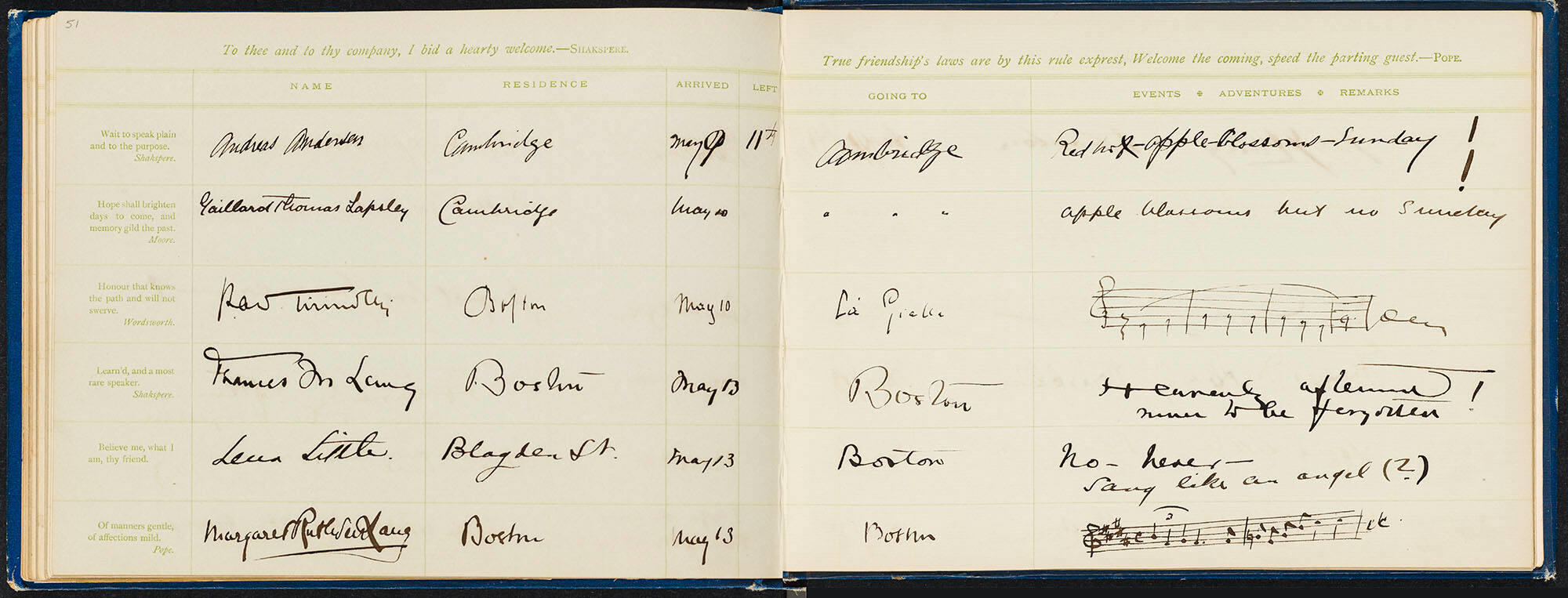

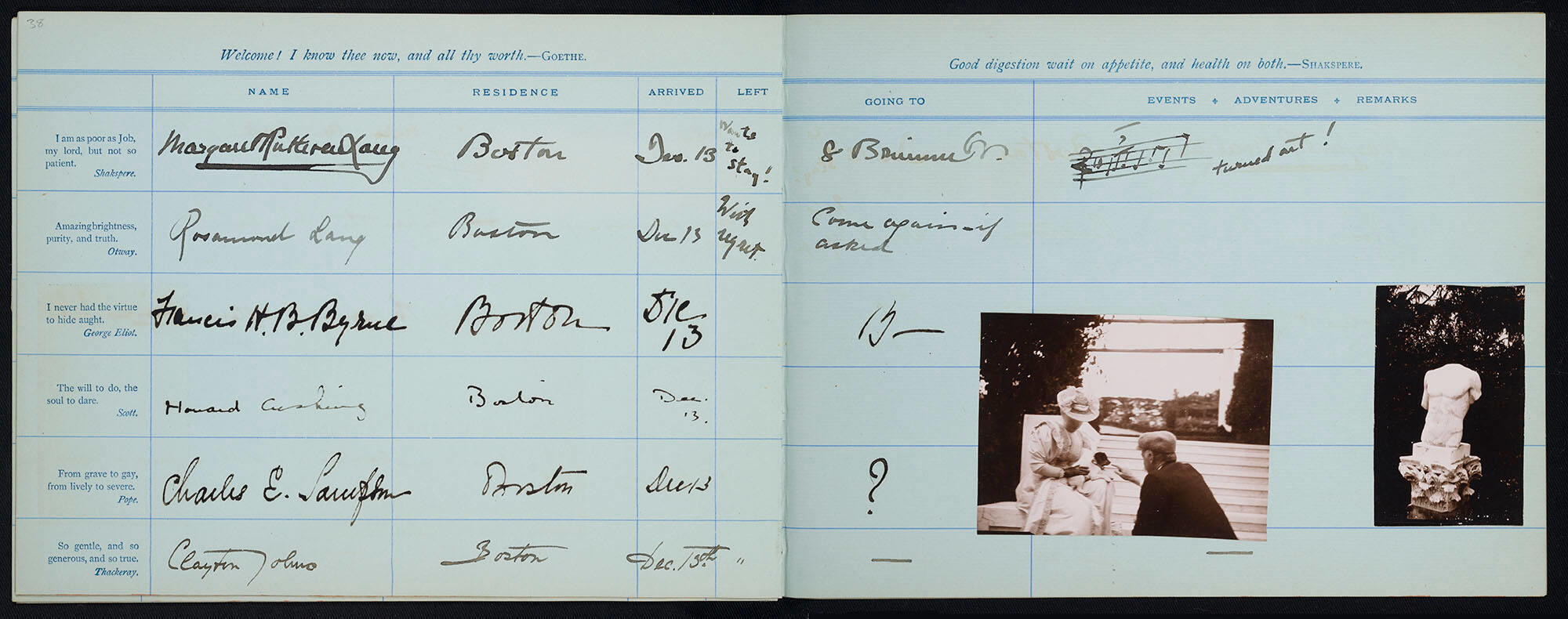

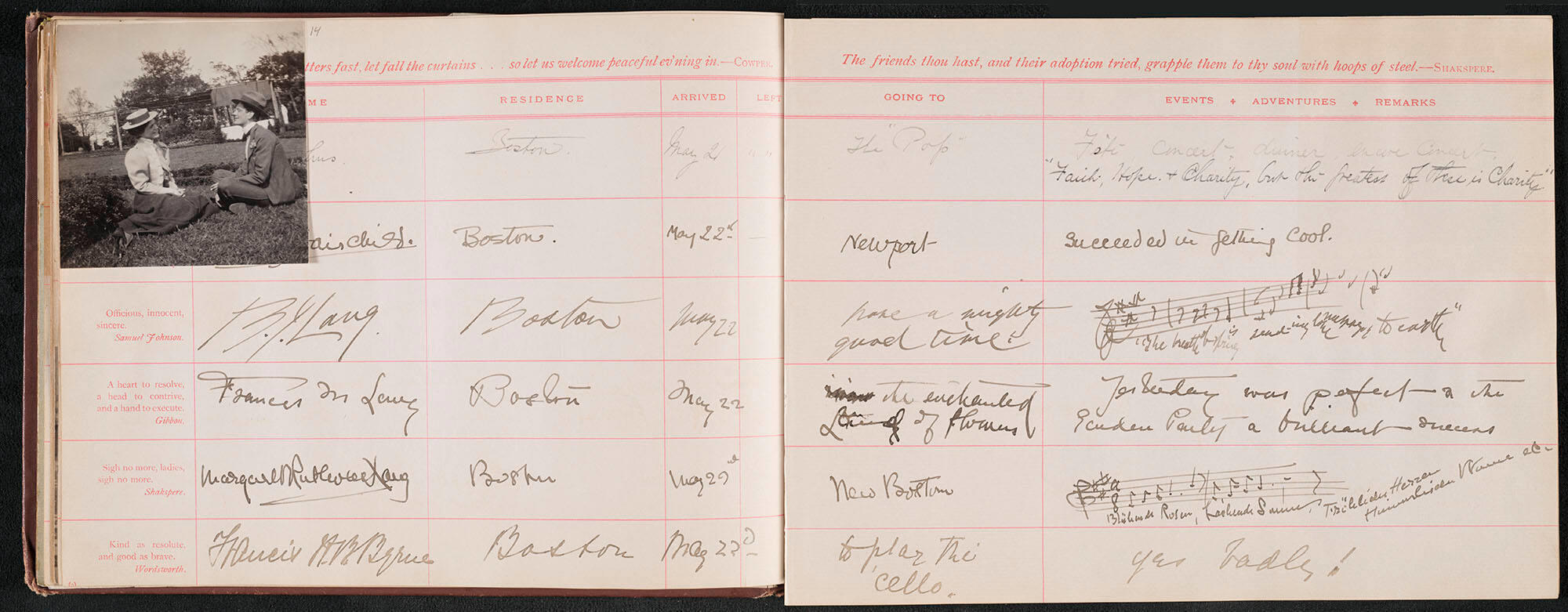

Several of Margaret’s visits with Isabella are documented in the latter’s guest books—and many of these entries also include a few bars of music in Margaret’s own hand!

THE MANUSCRIPT CLUB AT 152 BEACON STREET

Many social music clubs of the time met at the private homes of upper class women, in spaces like Isabella’s Music Room in her Back Bay home at 152 Beacon Street. These clubs were particularly important venues for promoting works by women composers like Lang.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.010186)

Thomas E. Marr (Canadian-American, 1849–1910), Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Music Room, 152 Beacon Street, Boston, 1900. Gelatin silver print

One of these clubs was called the Manuscript Club. It was one of the first places to program Margaret’s work. The club’s first performance took place on January 19, 1888 in Isabella’s Music Room. Margaret would have been twenty at the time.

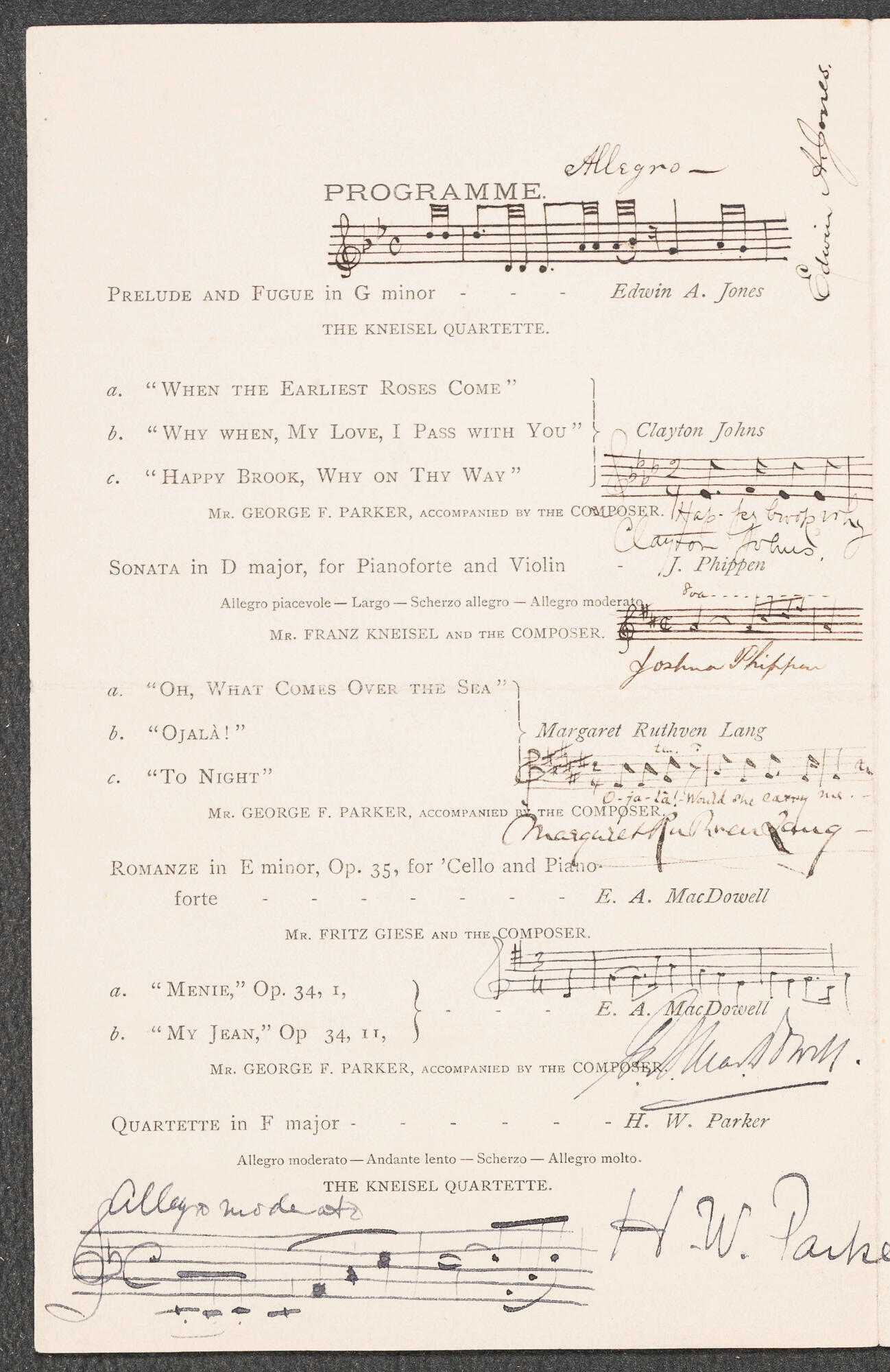

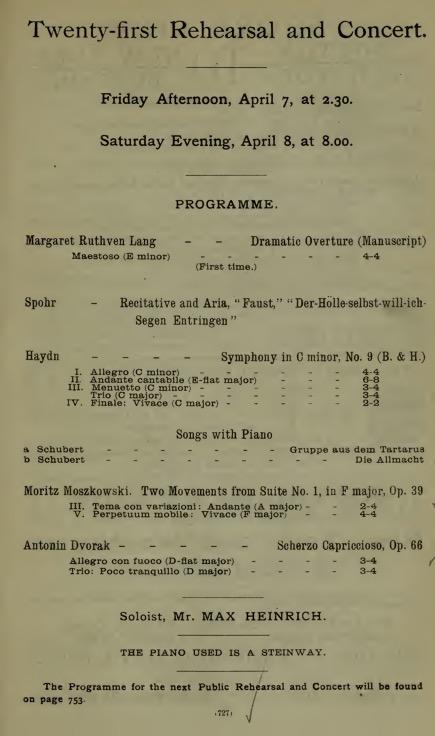

In addition to the program from the club’s first performance, Isabella kept one (ARC.007761) from the following year which featured Margaret’s song “Ojalà!” We can see a few bars of the melody written out on the printed program in Margaret’s hand, alongside the young composer’s autograph.

One of Margaret’s teachers, pianist and composer Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) (founder of the now famous MacDowell artists residency and workshop) showed Margaret’s music to the concert organizer at the 1889 Paris Exhibition (the very same that debuted the Eiffel Tower). That summer, “Ojalà” was performed at a concert there, in addition to becoming a song that would end up on concert programs all over the United States.

MARGARET AND THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

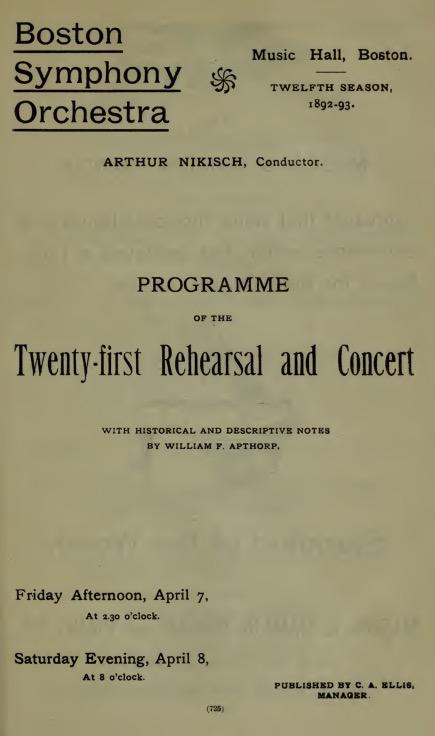

Both Margaret and Isabella shared a love for the Boston Symphony Orchestra since its founding in 1881 and on occasion the two attended together. Margaret’s friendship with BSO conductor Arthur Nikisch (1855–1922) allowed her to meet with orchestra members to discuss writing music for specific instruments, essentially using the orchestra as a kind of test kitchen.

Photo: Boston Musical Herald

Nathaniel Stebbins (American, 1847–1922), Arthur Nikisch with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, 1891

Although all of Margaret’s works for orchestra are now lost (they were unpublished), the most significant of these was her Dramatic Overture, op. 12 which premiered at the BSO under Nikisch on April 8th, 1893. This was the first time a work by a woman was performed publicly by an American symphony orchestra. Over seventy years later Margaret recalled her nerves that evening, saying, “I crept up to the balcony and hid.”¹

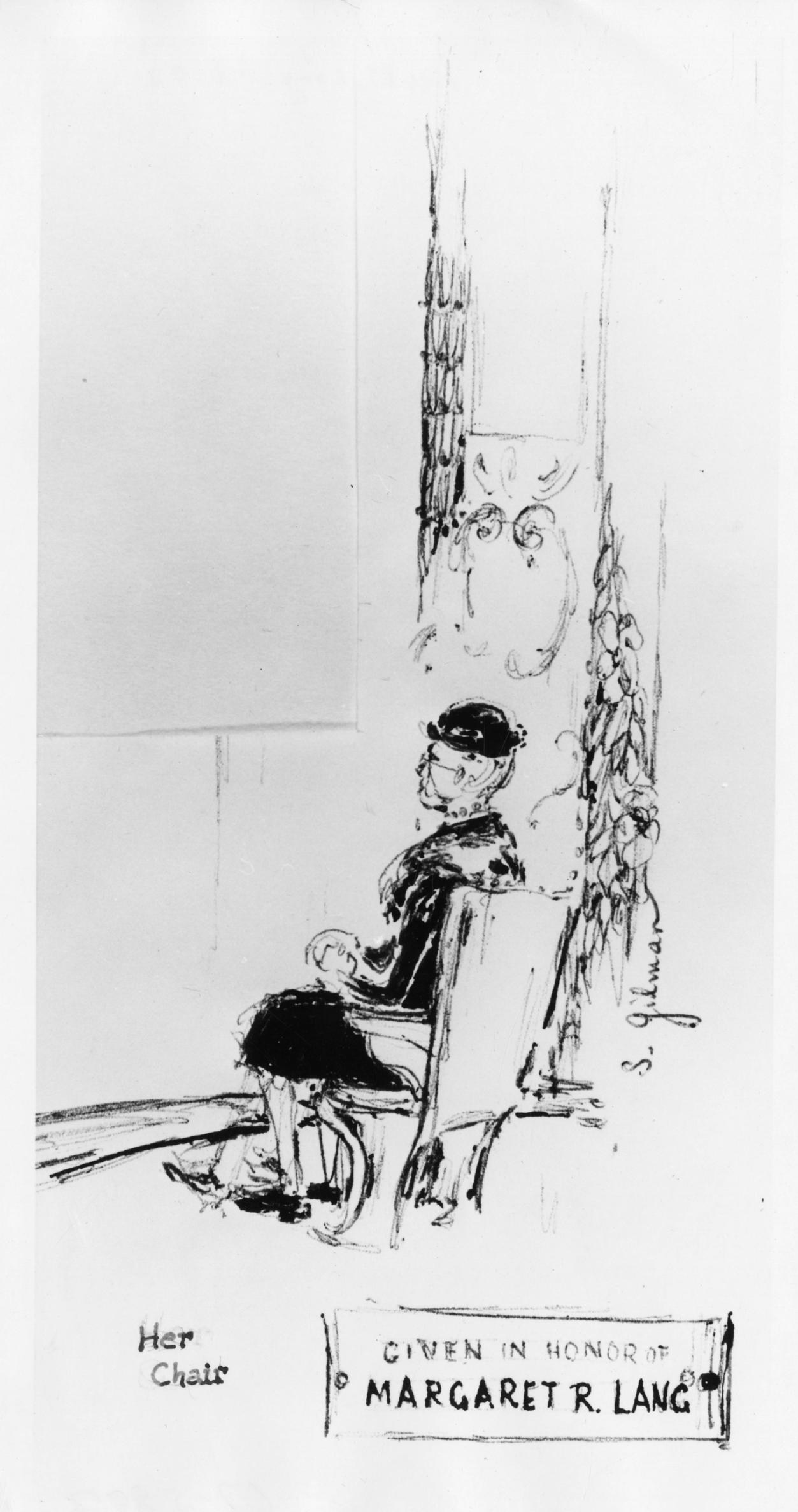

In 1967, the symphony celebrated Margaret’s 100th birthday at a concert with remarks on her legacy from the stage and two works she requested—she was also the symphony’s longest continuous subscriber. The first balcony seat (B1) she had occupied faithfully for all those years is adorned with a plaque in her honor.

Photographic reproduction by Photography Incorporated, Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives, Symphony Hall, Boston

Silvia Gilman (American, 1958–2014), Sketch of Margaret Ruthven Lang in her chair at Symphony Hall, after 1967. Ink on paper, 6.25 x 10 in.

A LOVE OF POETRY

Even though all of her orchestral works received performances, Margaret was best known for her songs and compositions for piano. Many of these indicate a passion for poetry and storytelling. Margaret included verses of poetry at the beginning of her piano works. Similar to the popular trend of “character pieces” at the time, clearly she wanted to acknowledge the words that inspired the music, even if the works were voiceless.

One of Margaret’s first published compositions for solo piano, Petit Roman, op.18 (1894), is based on a story Margaret wrote herself. She even wrote notes about the plot and character descriptions above bars of specific musical moments in the physical score. In 1900 Margaret said:

My intentions have been poetic and never purely (i.e., merely) musical, often dramatic and sometimes story-telling. I disapprove of pianoforte or vocal music which has no definite meaning to convey. I believe that pianoforte music would either paint a picture, tell a story or speak to the heart.

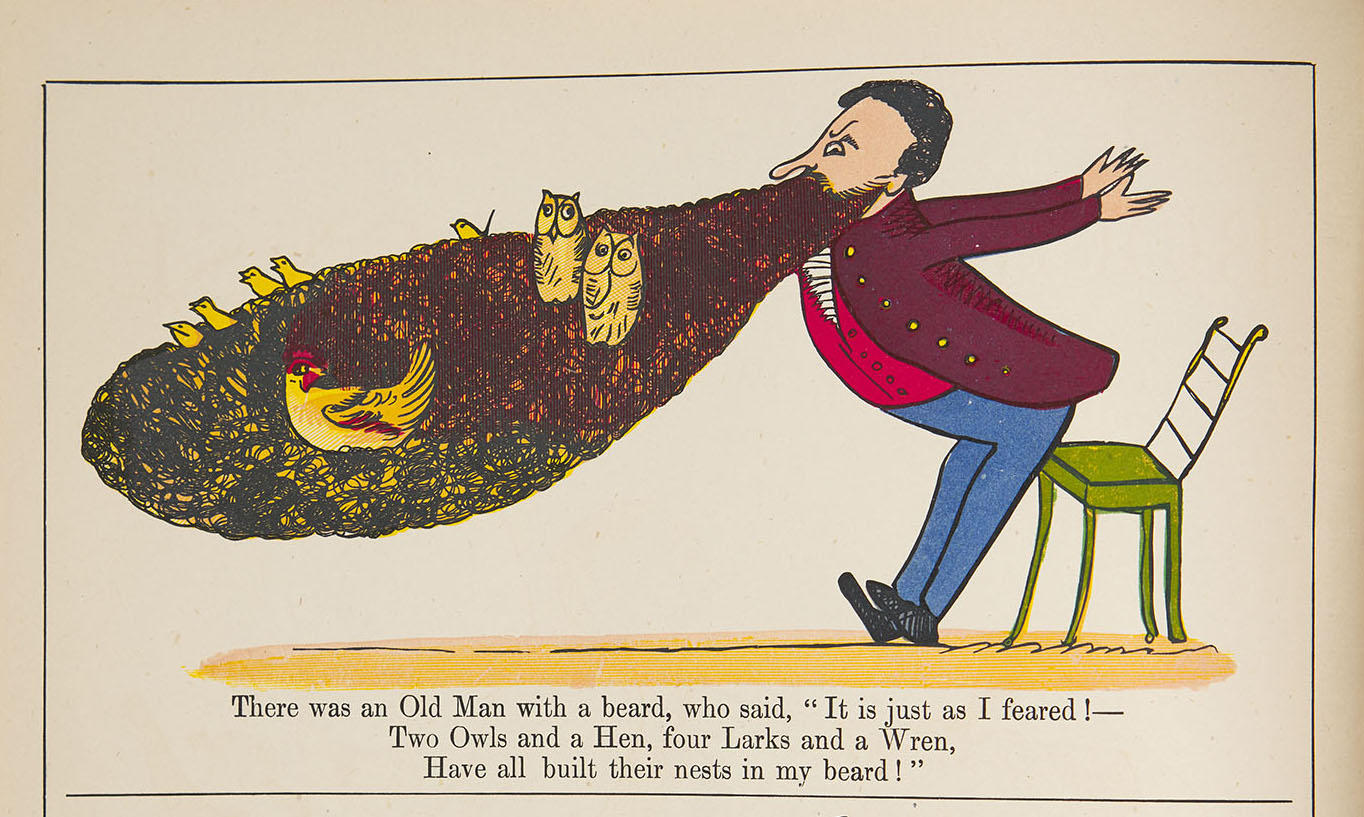

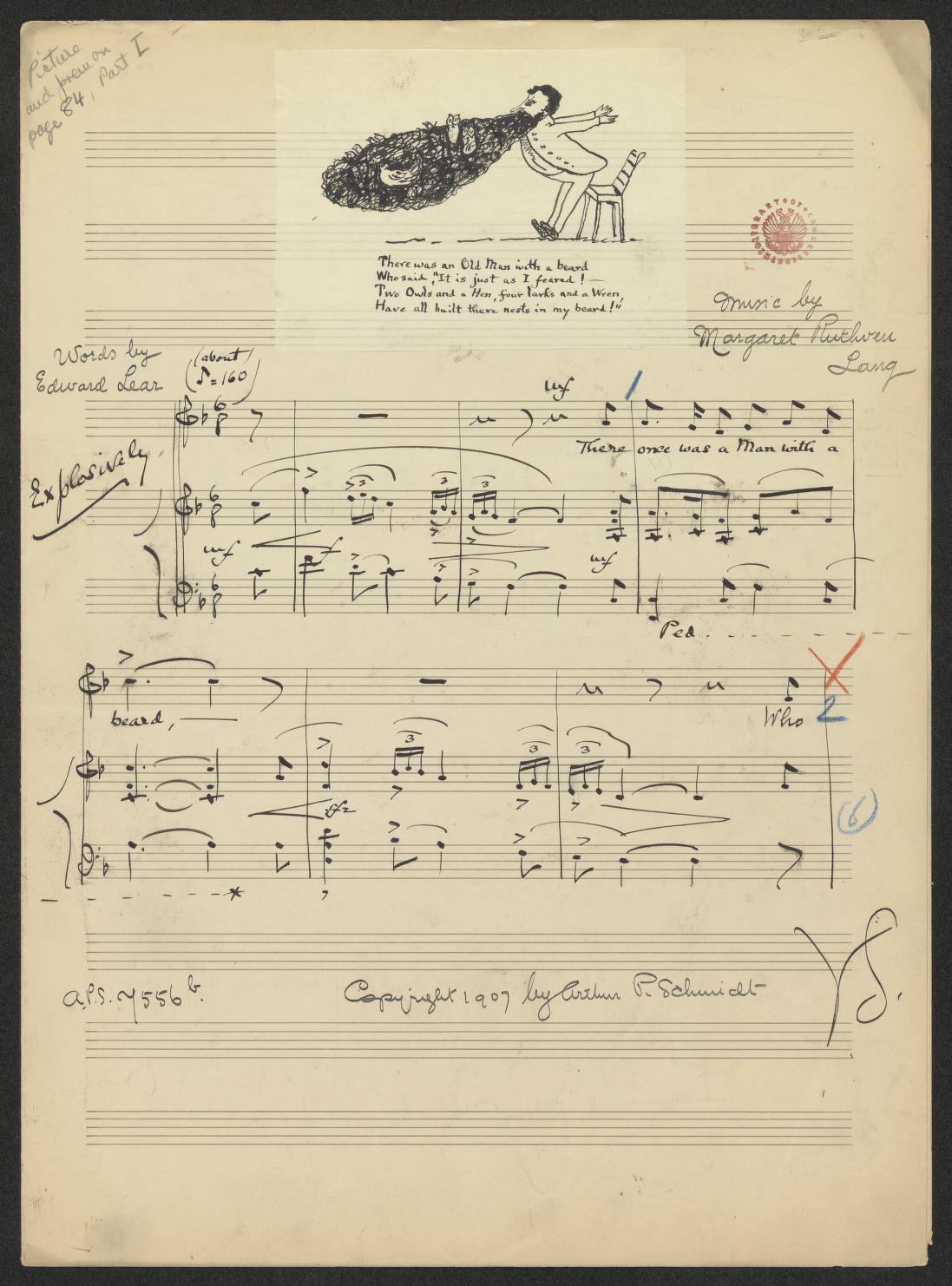

Apart from setting contemporary poems for voice, she also set two volumes of songs using limericks from Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense (which Isabella also owned). A few years after they were published, New England Magazine wrote: “These nonsense rhymes are the essence of refined wit, the best that America has ever produced in music.”

MARGARET’S LEGACY

In her early fifties, Margaret stopped composing and destroyed all of her unpublished music. Like many composers, she was critical of her own work—her father did the same with his own compositions. Margaret gave up her studio space to care for her ailing mother and the management of the family home, and eventually she began to write religious pamphlets (anonymously). She never married.

Isabella gave her Erard harpsichord to Margaret in memory of Margaret’s father who had passed away some years before. And of course, Margaret continued her patronage of the BSO. Towards the end of her life, she wrote in a letter to Marian MacDowell:

I am glad, very glad not to be active in any musical way, but only a thankful listener.

To hear more poetry set for voices, check out this upcoming concert at the Gardner: Ned Rorem’s Evidence of Things Not Seen, a song cycle of thirty-six poems set to music (including some by the very same poets Margaret used in her own work).

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Belle of the Opera: Gardner and Wagner

Read More on the Blog

Sound Check: First Concert Hall Audience

Read More on the Blog

Ethel Smyth: Composer and Activist

¹ Margo Miller, "Gentle World of the Past." Boston Globe, Feb. 19, 1967.