One of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s musical loves was the German composer Richard Wagner, best known for his monumental operas. Isabella went to great lengths to see these works, traveling many times to Bayreuth (a yearly music festival in Bavaria founded by Wagner to honor his own operas), taking every chance she could get to see his operas in the United States and Europe, and collecting scores and librettos. Isabella was a true musical connoisseur who wanted to be at the center of the most exciting musical happenings of her time and, during her lifetime, Wagner was at the epicenter of the classical music world. Hidden Wagnerian gems are scattered across the Museum’s galleries if you know where to look.

Friedrich Bruckmann (German, 1814–1898, photographer), after Georg Papperitz (German, 1846 –1918, painter), Richard Wagner and Friends in Bayrueth, about 1880. Albumen print on card

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.006312). Isabella displayed this photographic print in the Musicians Case in the Yellow Room

The most visible token of Isabella’s love for Wagner in the Museum is a richly detailed set design for one of Wagner’s operas. Displayed in the Vatichino, this colorful drawing was a gift from Isabella’s friend Joseph Urban, a renowned architect and set designer who designed over 50 productions for the Metropolitan Opera and served as the art director of the Boston Opera Company. Urban gave this drawing of the set design for the 1914 Boston Opera Company production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg to Isabella for Christmas later that same year, presumably after she saw and loved the production.

Joseph Urban (Austrian, 1872–1933), Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg [The Mastersingers of Nürnberg]: Second Act in the Streets Before the Houses of Pogner and Sachs, early 20th century. Pen and ink, watercolor, and gouache on paper

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See it in the Vatichino

Urban described the theater as “a place in which to experience a heightened sense of life," a statement which also aptly describes the Gardner Museum. Wagner himself used the word gesamtkunstwerk to describe his approach to art. Often translated as “total work of art,” he used this word to describe how his operas united music, narrative, orchestration, singing, acting, set design, costumes, and even the architecture of the theater into a single transcendent work of art. It’s no wonder that the integrated artistic experience of Wagner’s operas struck a chord with Isabella, who herself created a Museum that seamlessly fuses art, architecture, horticulture, and music to create an immersive artistic world.

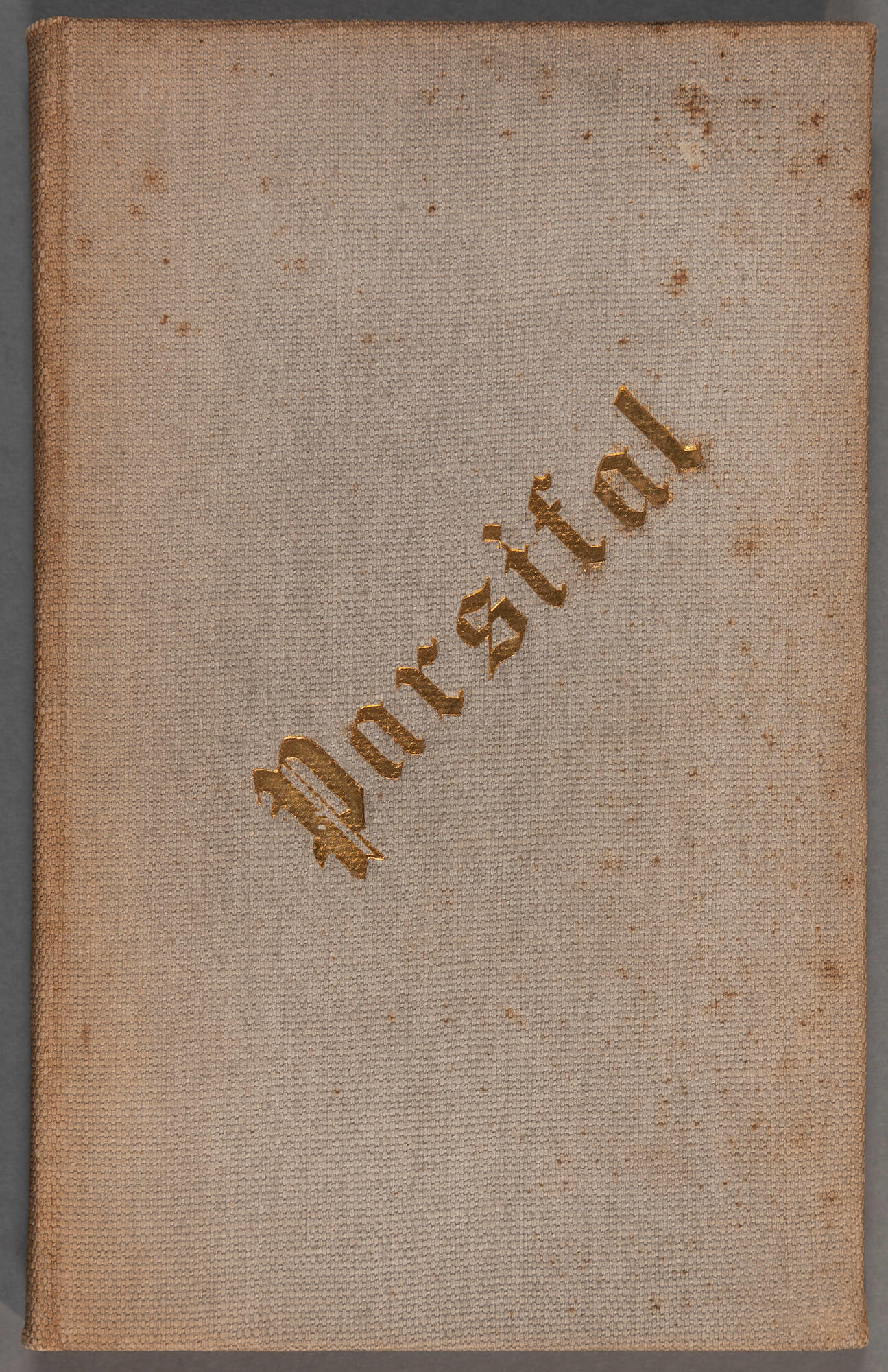

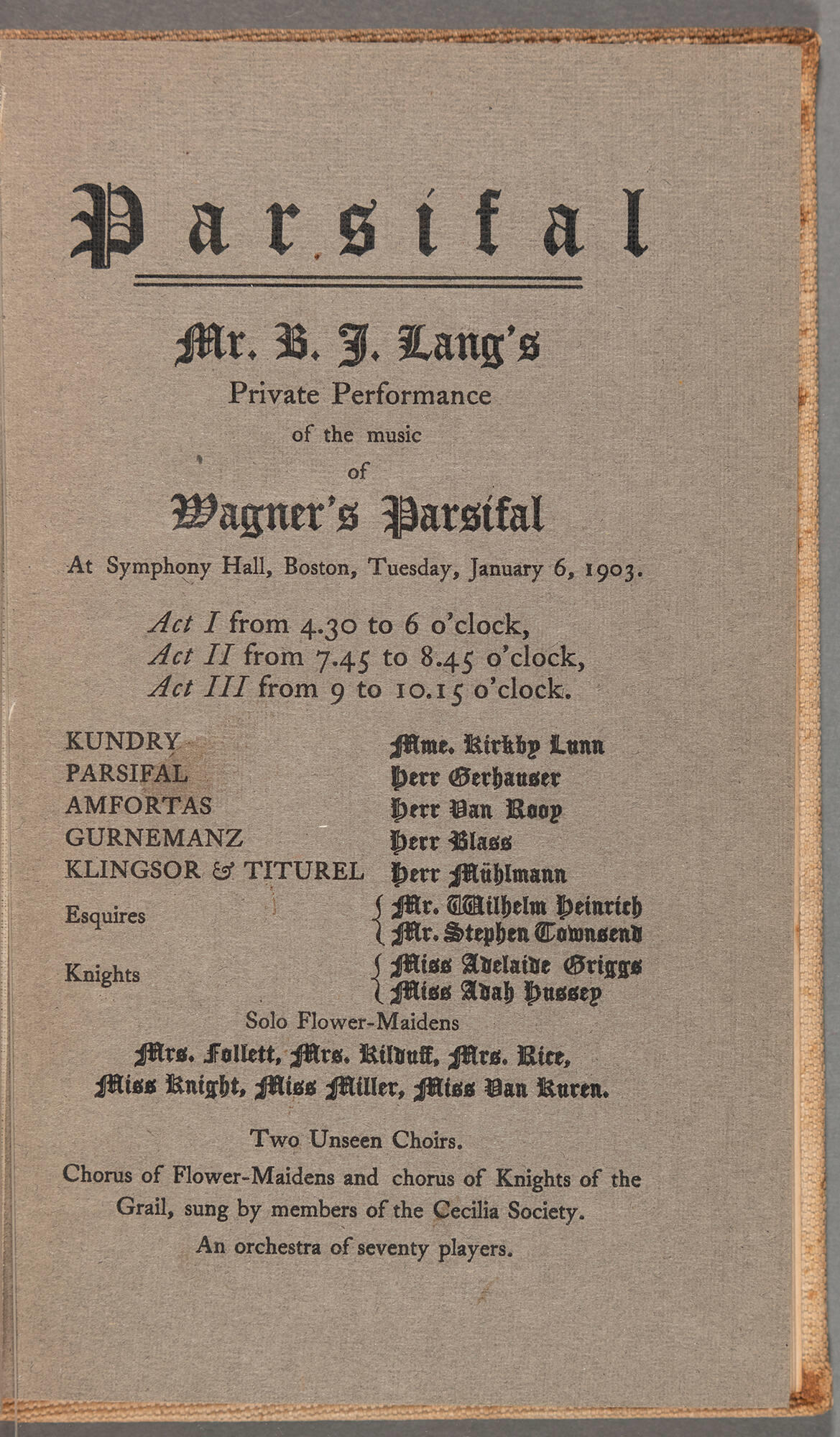

Note on a visiting card from American conductor B.J. Lang (American, 1837–1909), accompanying his gift of Parsifal: Libretto to Isabella, Christmas 1903

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.002466)

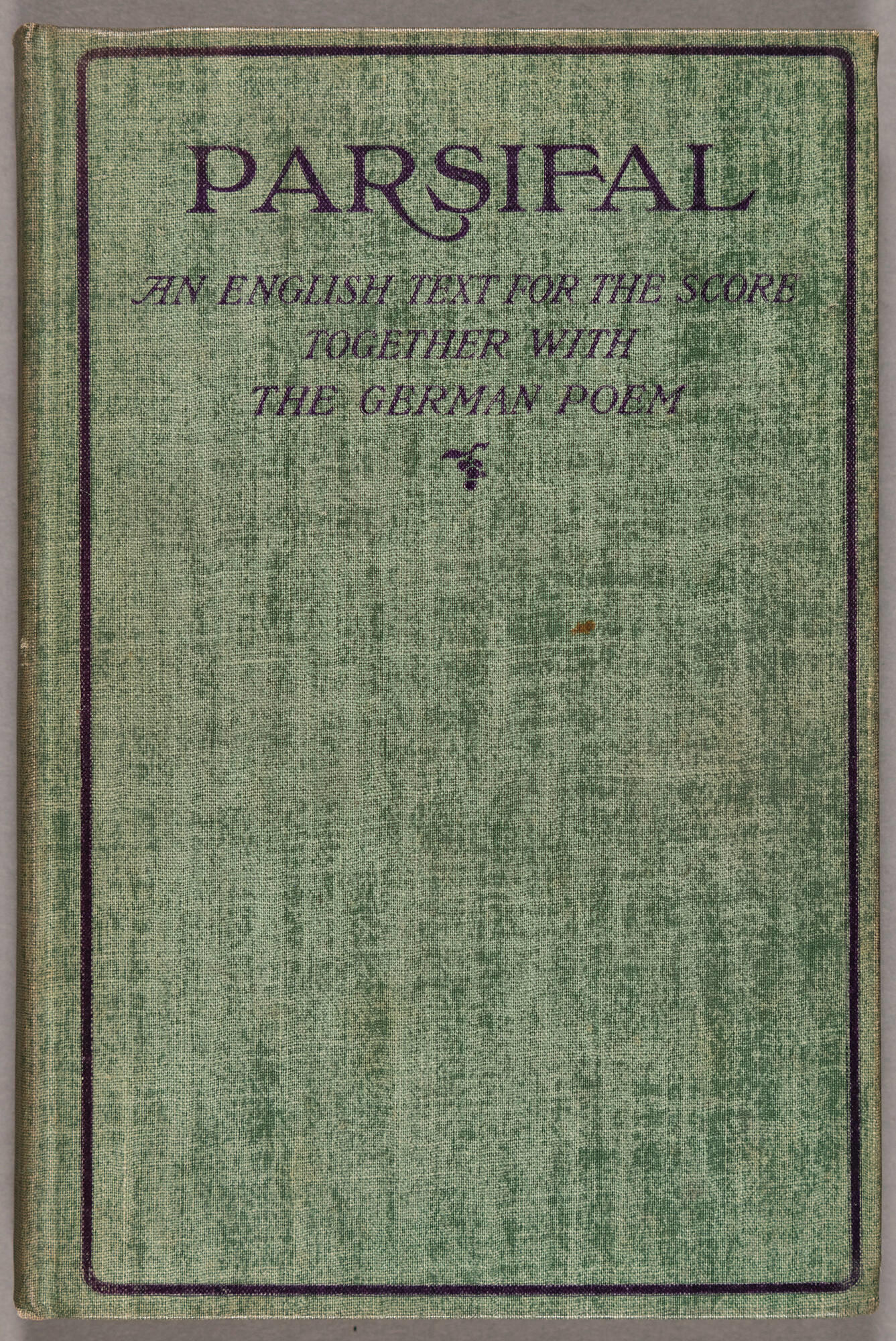

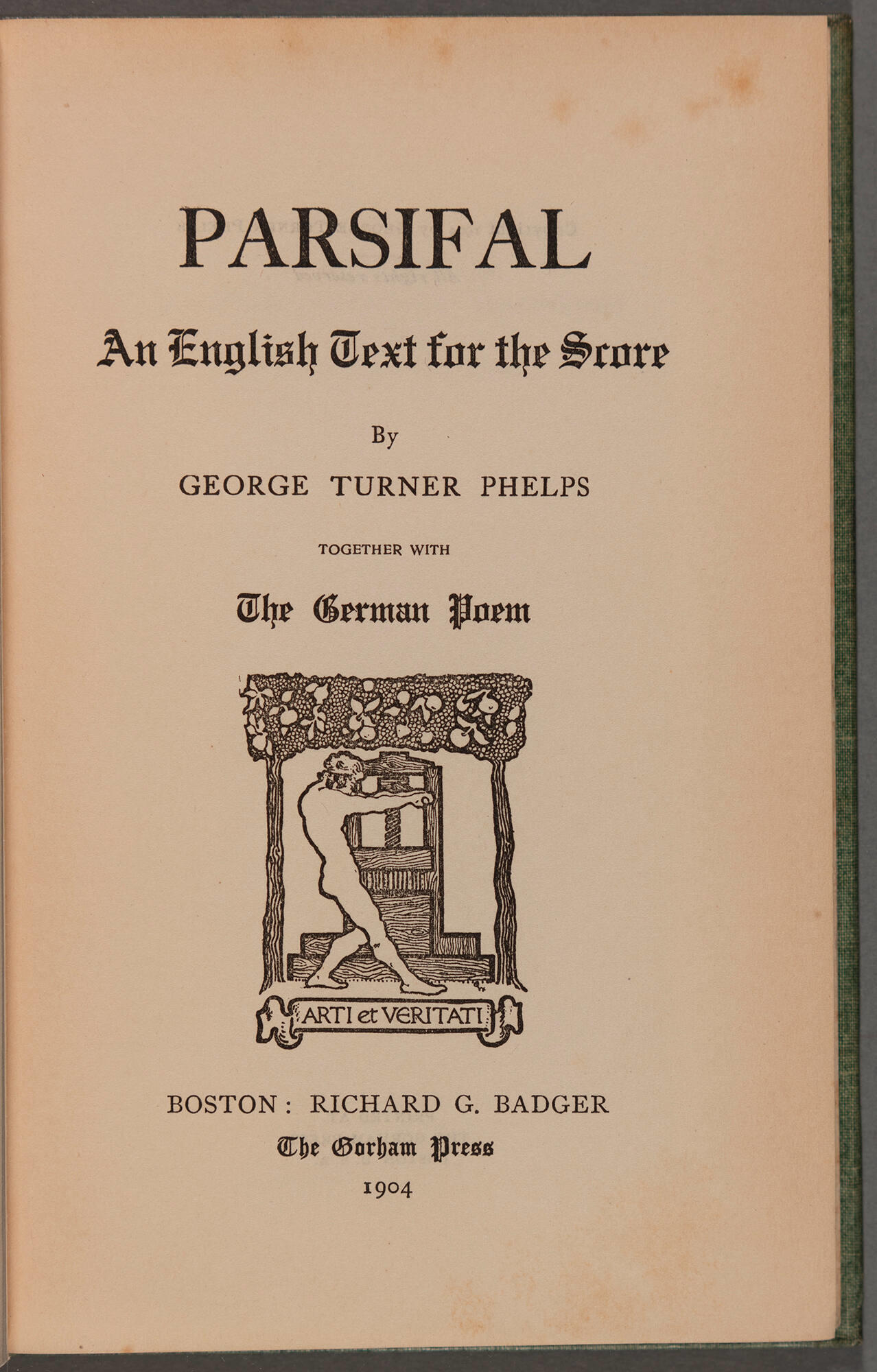

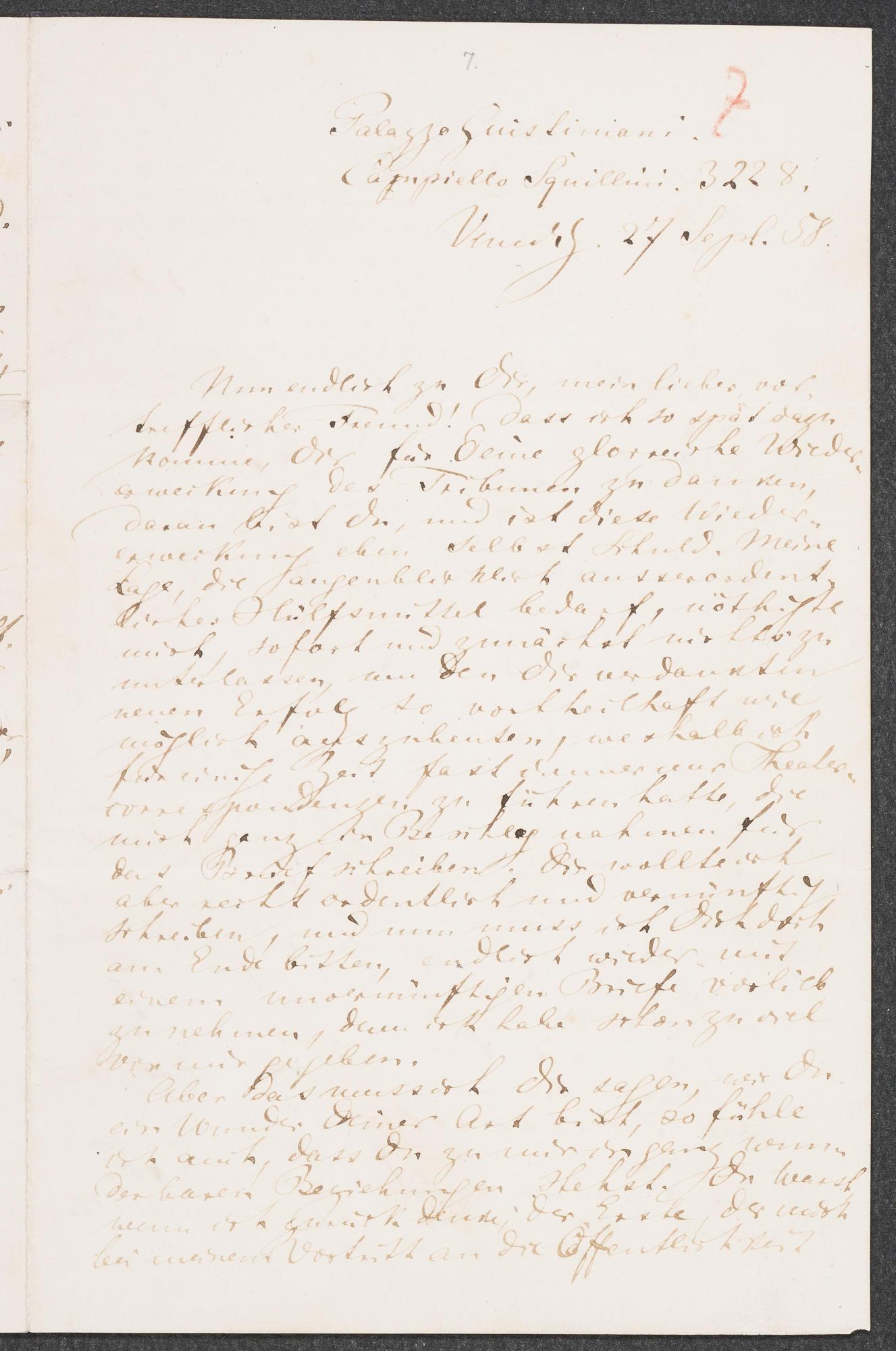

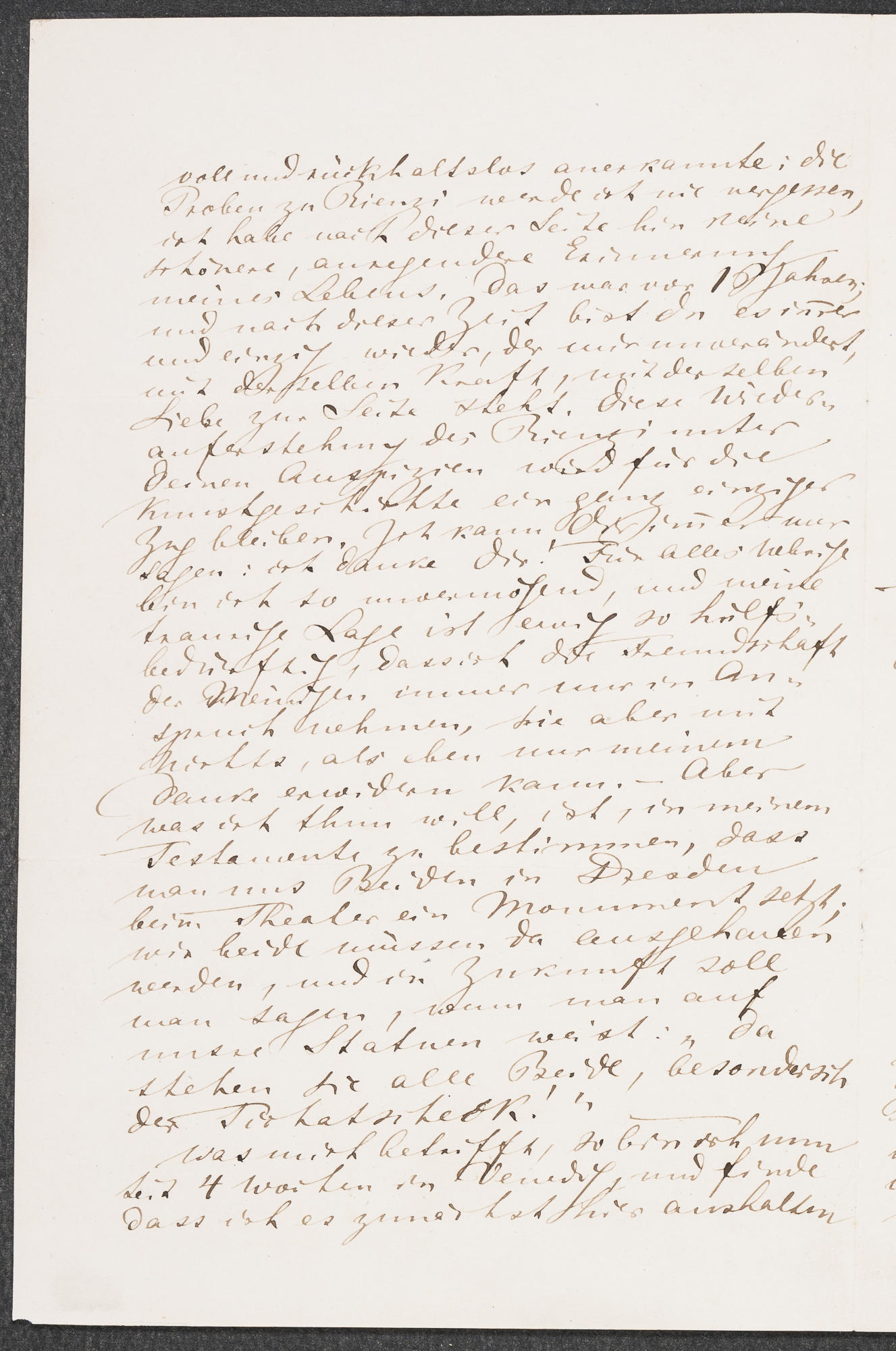

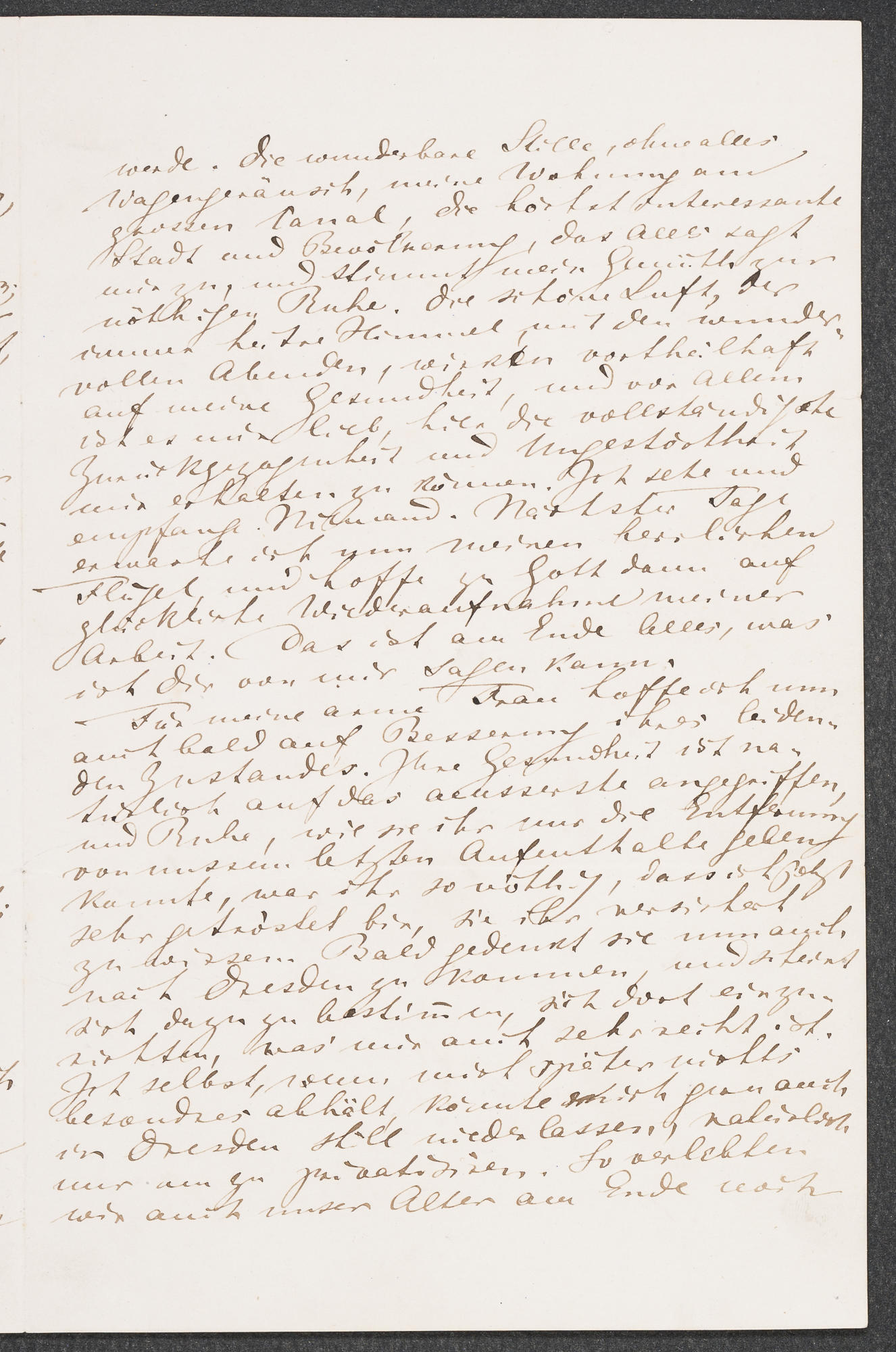

However, this isn’t the only Wagner-themed Christmas gift Isabella received. For Christmas in 1902, conductor B.J. Lang gave Isabella a libretto for Wagner's opera Parsifal. Lang was an important Boston-based freelance conductor who gave the world premiere of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, which took place in Boston. He gave Isabella this libretto in anticipation of a private performance of Parsifal he was conducting at the recently-constructed Symphony Hall two weeks later. His note accompanying the gift reads:

It seems as if you ought to have a better Parsifal than ordinary folk.

For over 20 years, staged performances of Parsifal were only allowed to take place at Bayreuth. The festival had a monopoly on staged performances of the opera, so the performance Isabella attended on January 6, 1903 was likely a very special, rare, private event for opera lovers who were incredibly eager to experience this hard-to-hear work. Isabella’s libretto from Lang, along with a second libretto for Parsifal that she collected, are also both housed in the Vatichino.

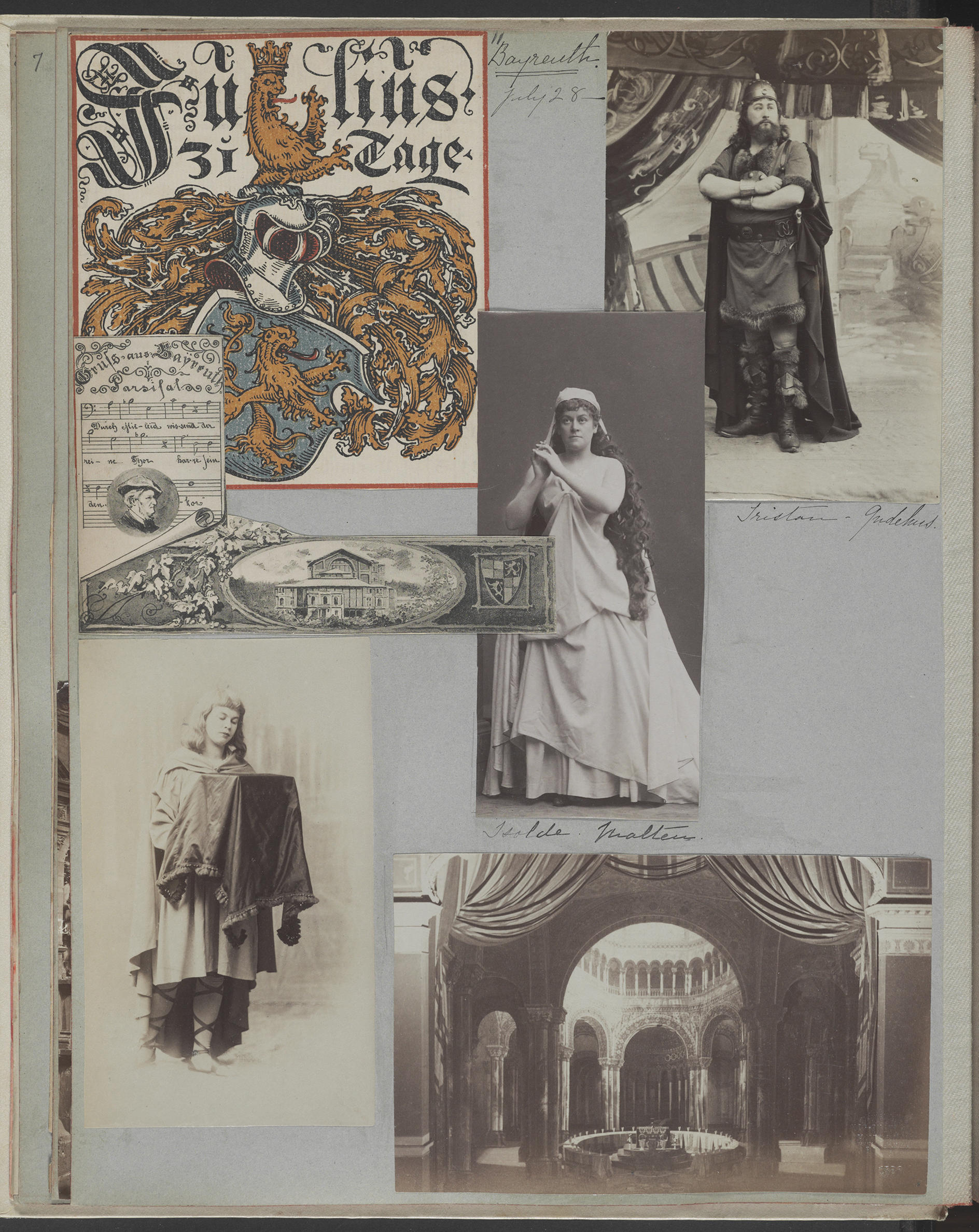

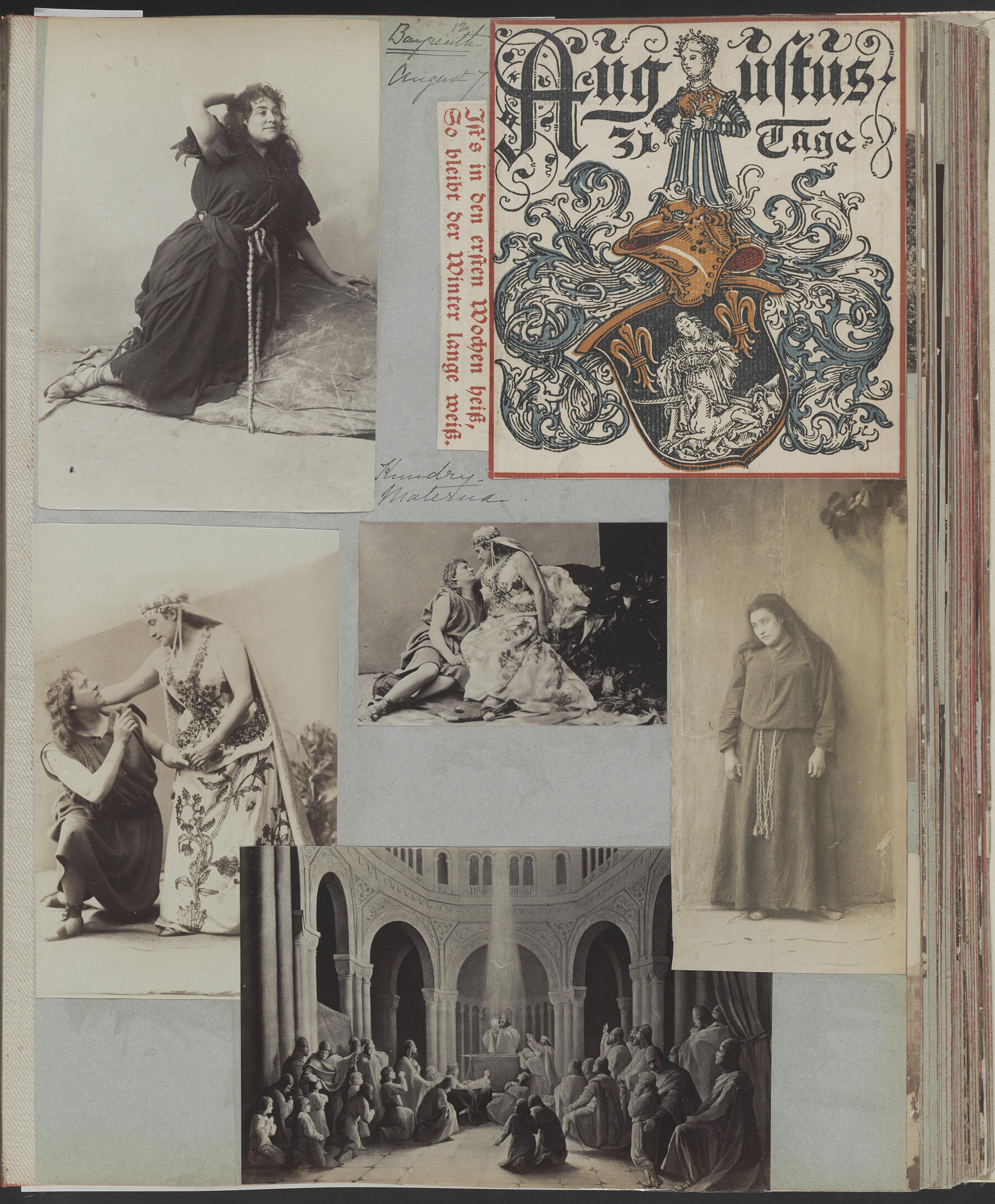

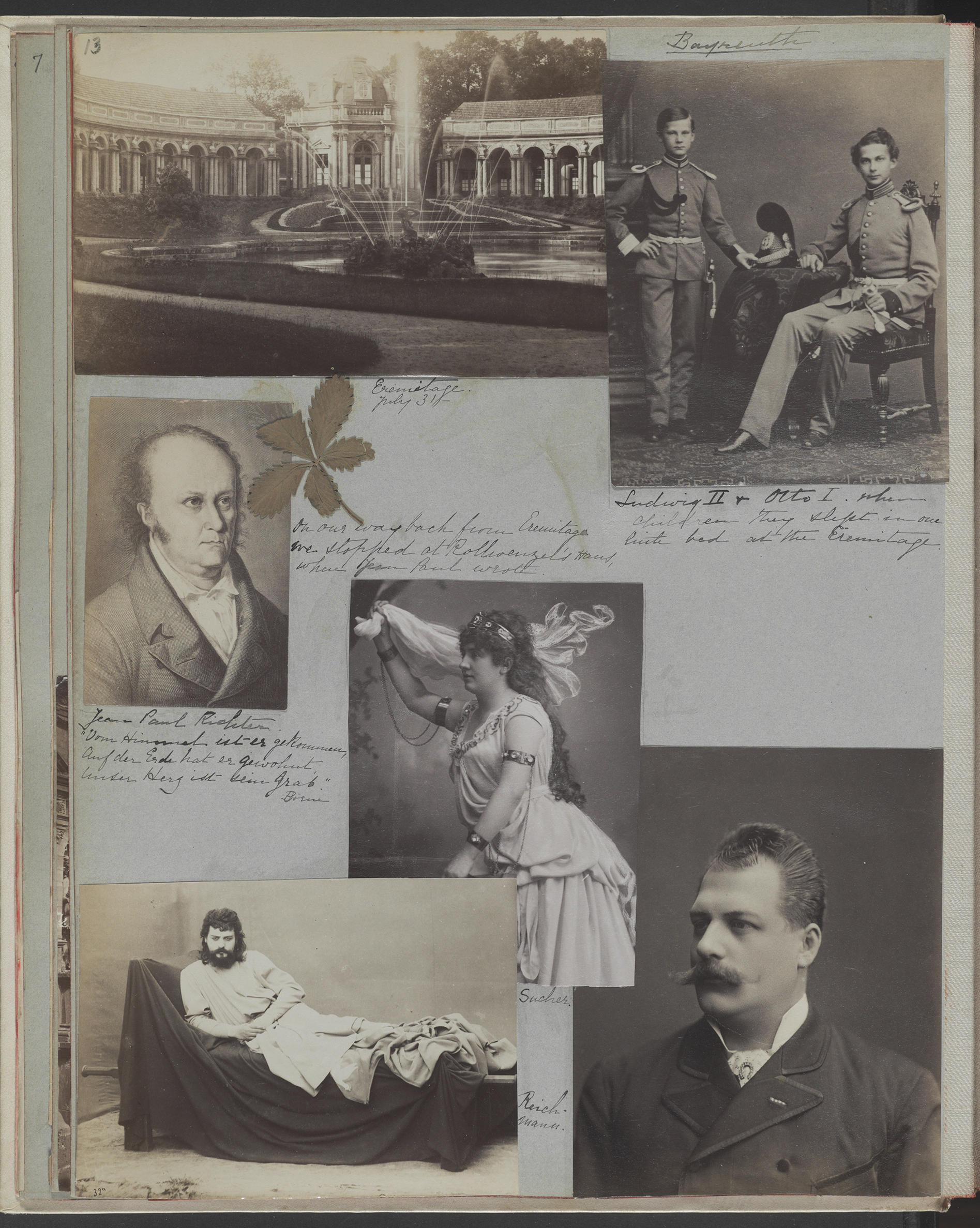

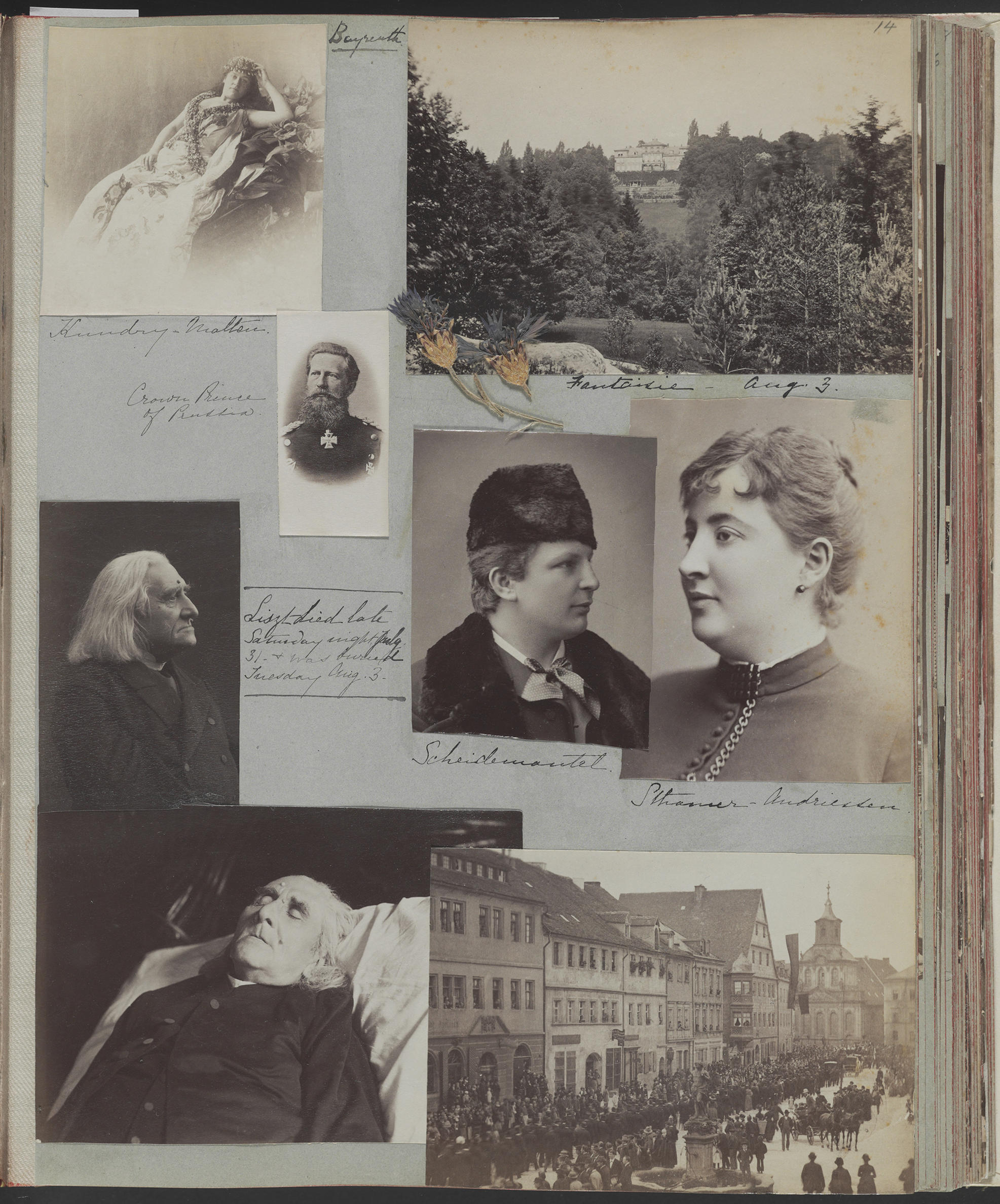

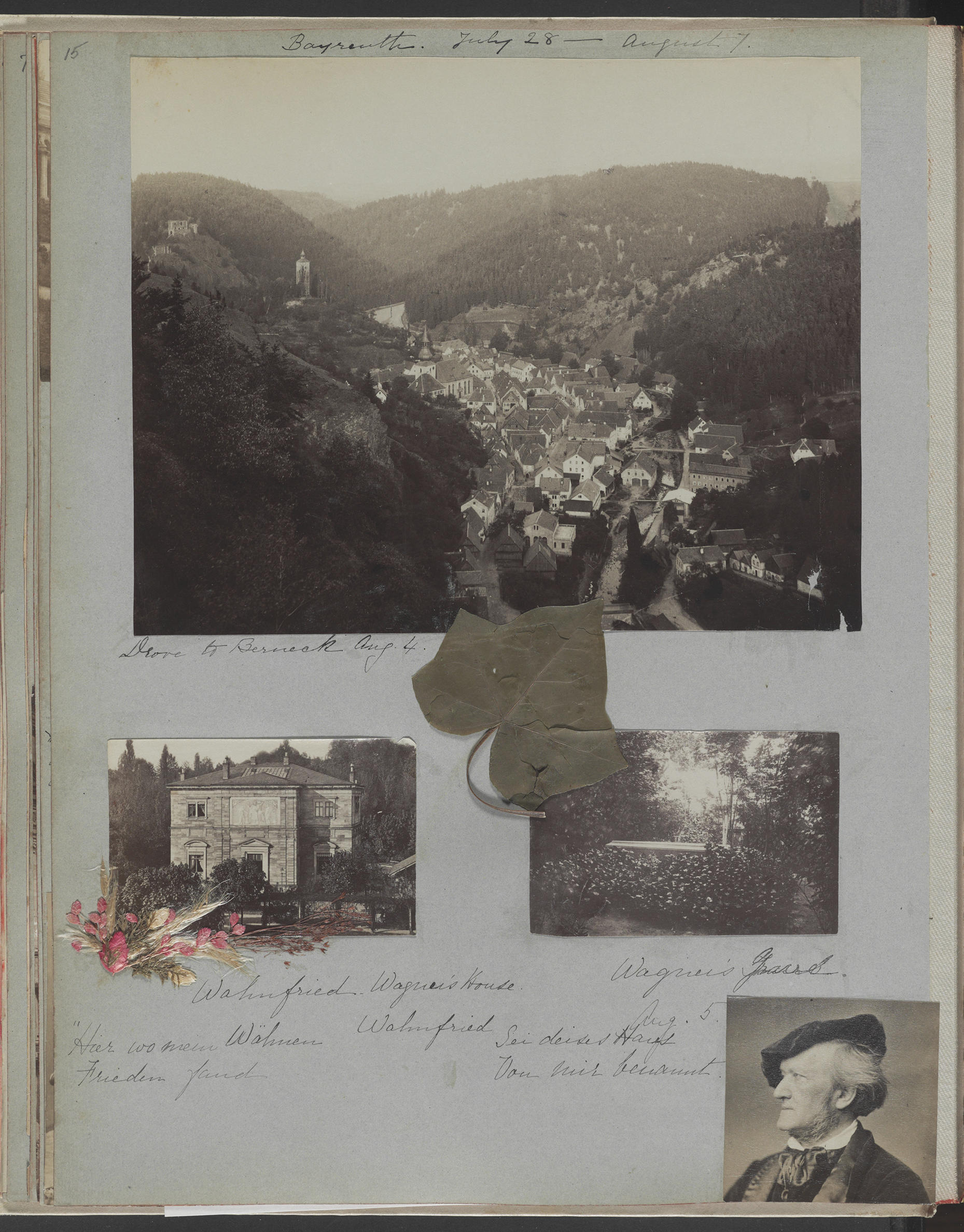

Isabella made her first pilgrimage to Bayreuth in 1886, and she documented the trip with photos, botanical samples, and annotations meticulously saved in a travel album.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840–1924), Travel Album: Great Britain, France, and Germany, 1886. Page 15, Bayreuth, Germany, July 28 - August 7

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Isabella kept her travel albums in the Vatichino, her personal treasure trove

The Bayreuth Festival is a revered place for music connoisseurs because of its faithful embodiment of Wagner’s philosophy of art. Isabella’s travel album provides a glimpse of her experiences, what mattered to her, and what she wanted to preserve. There are photos of the town, the opera house, her favorite singers, and even an image of the original Act I set for Parsifal, which had debuted in 1882, just a few years earlier. Isabella was at Bayreuth right from the beginning—Parsifal had just recently debuted, Wagner himself had died just three years earlier, and many of the singers she saw were the very performers who had originated the roles in Wagner’s operas.

Isabella was eager to meet towering musical figures at Bayreuth, including Franz Liszt, a renowned composer and the father of Wagner’s wife. Unfortunately, during her first trip to Bayreuth in 1886, Liszt passed away at the festival, and Isabella included photos of Lizst alive and dead in her album to commemorate his passing. She attended his funeral, where she cast the first shovel of earth on his coffin, and she saved a lock of his hair in a decorative box found in the Musicians Case in the Yellow Room.

Isabella returned to Bayreuth many times, where she collected many mementos of her trips, including a beautiful folding fan from her 1892 trip, housed in the Vatichino. This fan is covered with iconic images of a Parsifal score, Wagner himself, his house, and the opera house which Wagner had expressly designed to house his operas which required huge orchestras, magnificent sets, and a completely immersive viewing experience. On this same 1892 trip, she collected one of her most sentimental mementos from Bayreuth, a pressed ivy leaf she collected from Wagner’s grave. Tucked away in an envelope in the Vatichino, it’s labeled in Isabella’s own handwriting.

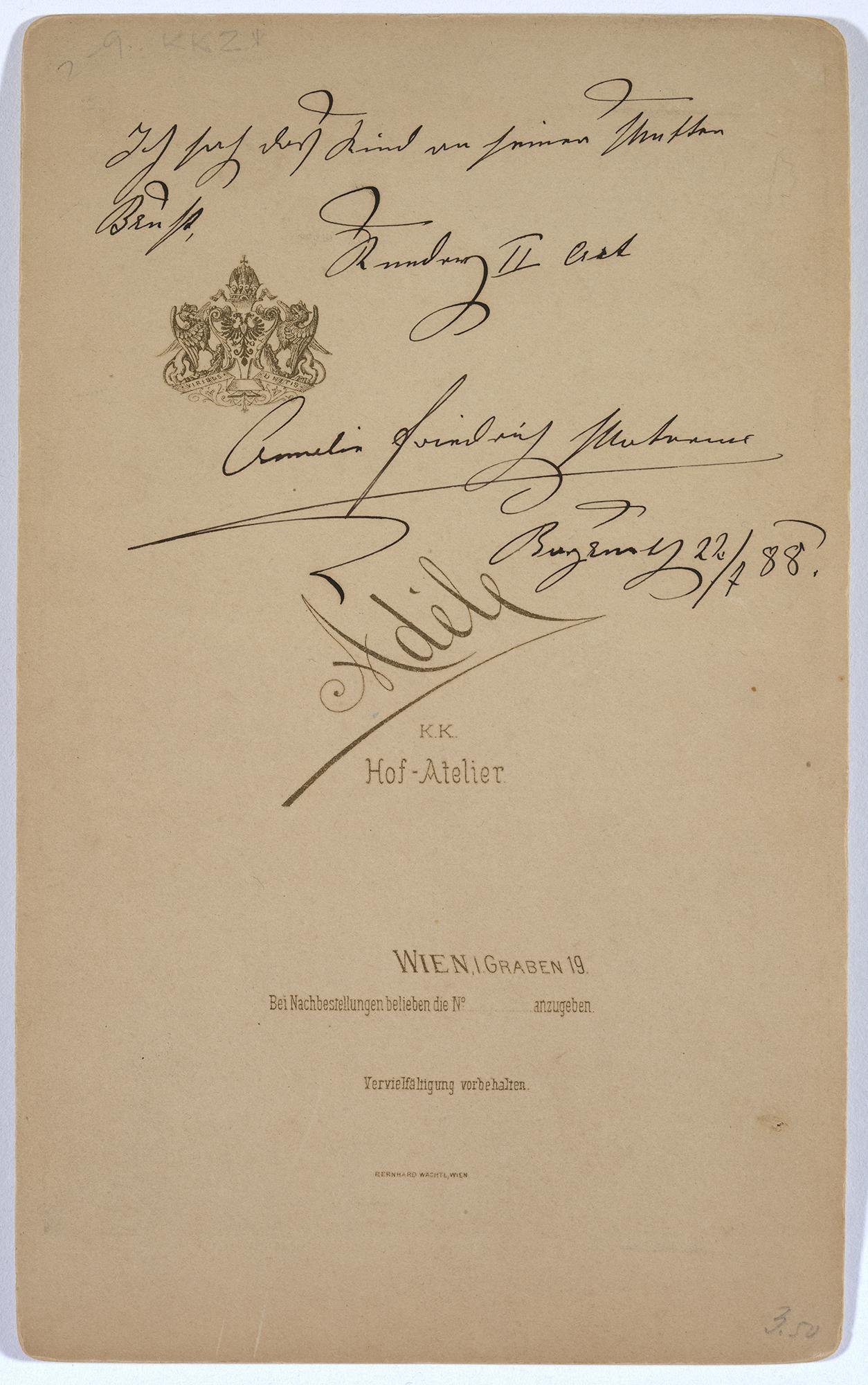

A few pieces of Wagner memorabilia can also be found in the Yellow Room, including signed photos of some of the singers Isabella saw perform at Bayreuth. One of these portraits is of the legendary Wagnerian soprano Amalie Materna, who originated several lead roles in Wagner’s operas, including Brünnhilde in the Ring Cycle, Wagner’s famed four-part operatic series. In 1888, following a performance of the Ring Cycle, Isabella followed Materna to the house of Wagner’s widow Cosima (who was also Franz Liszt’s daughter!) to attend a post-performance party. Isabella was warmly welcomed by Cosima, and stars including Materna sang snippets from the operas all night long. Recalling this night, Boston composer Clayton Johns wrote, “Frau Cosima received us graciously, particularly Mrs. Gardner. Materna (Wagner’s original Brünnhilde) sang a scene from Götterdämmerung and other stars obliged with selections until it was early morning.”

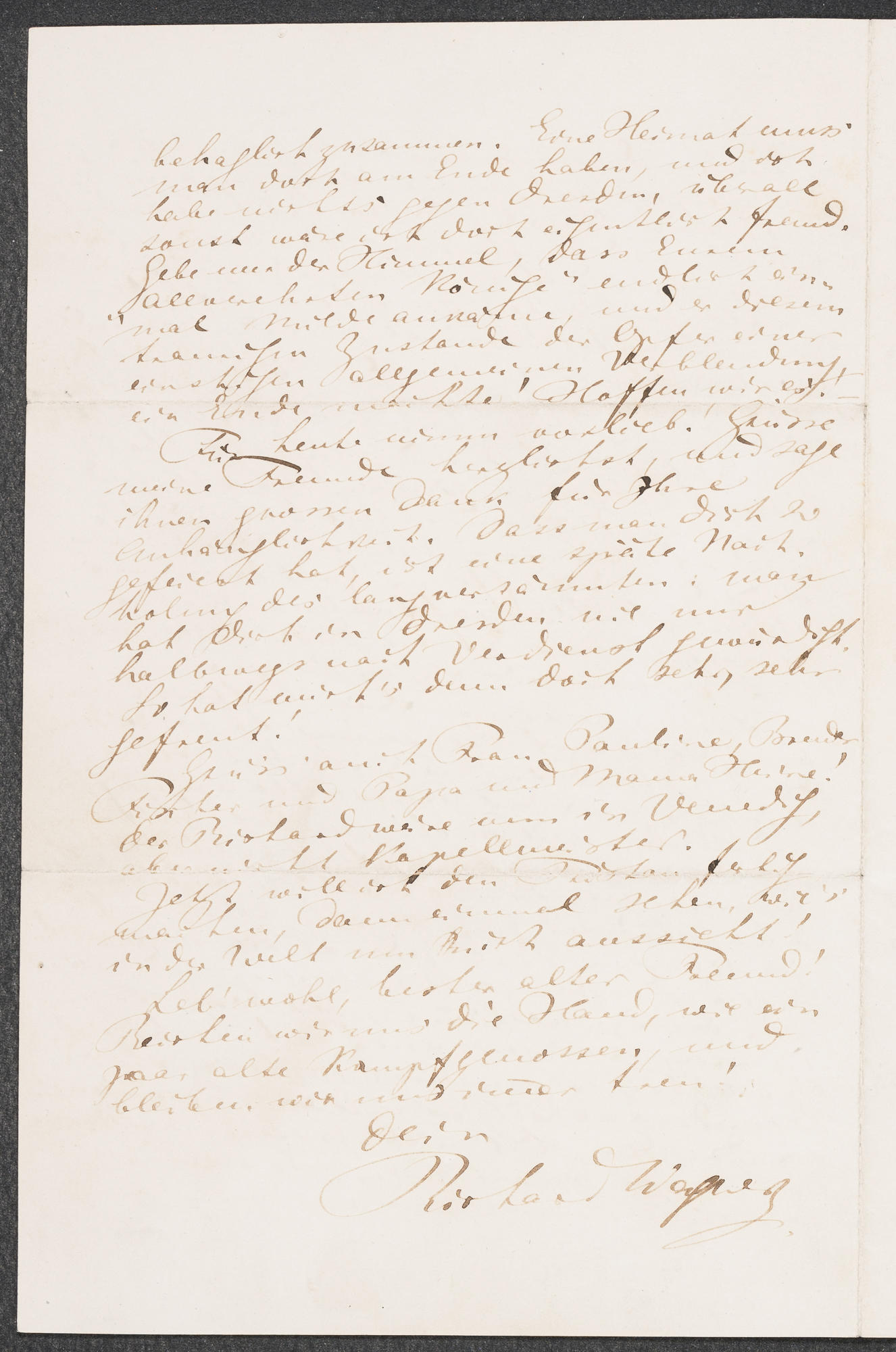

Displayed alongside these photos is the ultimate prize for a Wagner fan, an autograph letter in Wagner’s own hand. An incredible artifact for any music collector, this letter must have been especially exciting for a devoted Wagner fan like Isabella.

However, Isabella was not alone in her Wagner mania. In Boston today, there are still tributes to the huge cultural phenomenon Wagner’s operas created during Isabella’s lifetime. The Swan Boats, which operate in the Public Garden, were actually inspired by Wagner’s opera Lohengrin, in which the hero appears to his damsel in distress on a boat drawn by a swan.

Swan Boats on the Boston Common, 2017, inspired by Wagner’s opera Lohengrin

Beyond My Ken, CC BY-SA 4.0

Robert Paget and his wife Julia, who had a concession to operate boats in the Public Garden, saw Lohengrin in the late 19th-century and designed the swan boats after Wagner’s hero in order to bring some of his mythic romance to Boston. The boats made their debut in the Public Garden in 1877, at the height of the Wagner craze in Boston, and they’re still going strong today.

You May Also Like

Learn about Music at the Gardner

Witness: Spirituals and the Classical Music Tradition

Learn about the Gallery Cases

The Fifteen Cases

Read More on the Blog

American Impressionism and a Piano Trio