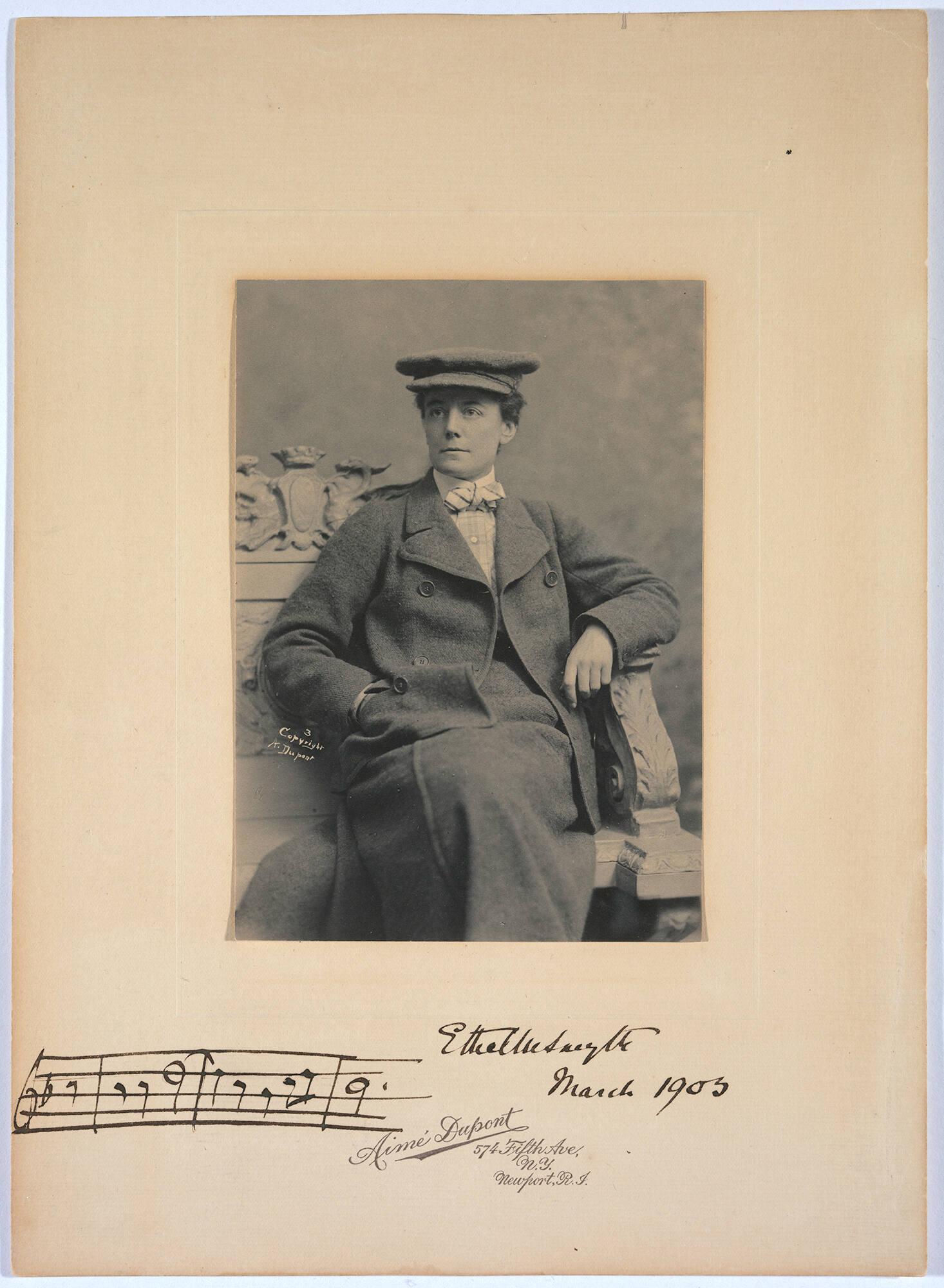

The Yellow Room’s Musicians Case displays letters, scores, and depictions of many notable performers and composers. However one item stands out: A signed photo of Ethel Smyth. It is the only photograph of a woman composer Isabella Stewart Gardner included in this shrine to her favorite musicians.

Musicians Case in the Yellow Room

Photo by Sean Dungan. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

An Underrated Composer

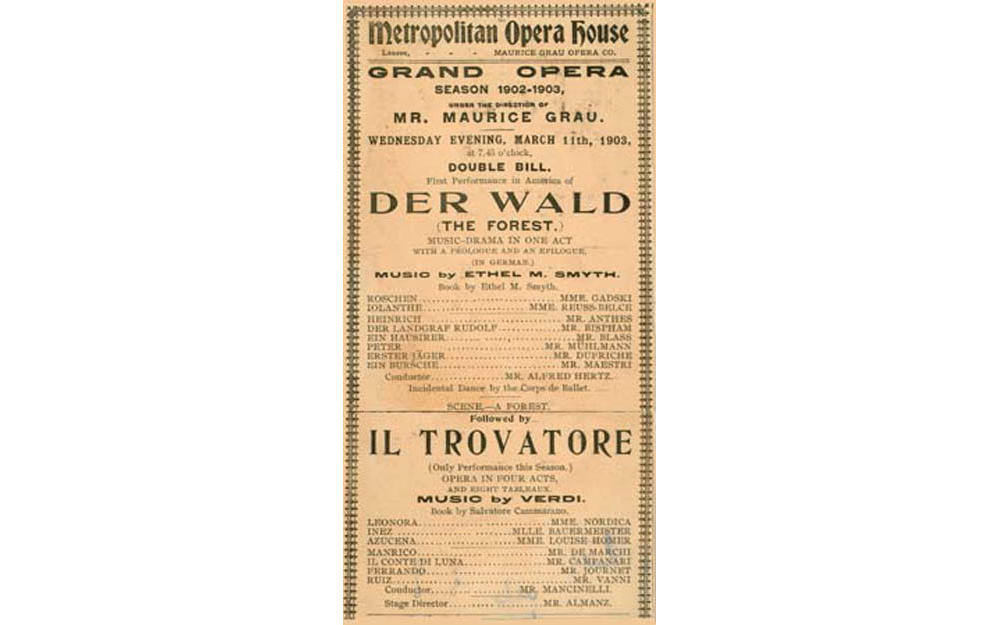

Ethel Smyth was a trailblazing English composer and contemporary of Gardner. Her opera Der Wald (The Forest) was the first work by a woman composer performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. It remained the only opera by a woman composer staged at the Met for the next 113 years, until 2016. The New York Times dismissed Der Wald as a “disappointing novelty,” saying “The case is one of vaulting ambitions and a general incompetency to write anything beyond the most obvious commonplaces. It is quite lacking...in distinction of any kind.” Beyond its negative view of Smyth’s compositional skills, the review’s focus on “vaulting ambitions” reveals a hostility towards the fact that a woman dared put her work on the biggest opera stage in the United States. Despite her major accomplishments, Smyth recognized that the discrimination she faced could undermine her work. “The exact worth of my music will probably not be known till naught remains of the writer but sexless dots and lines on ruled paper,” she said.

Playbill for the premiere of Der Wald at the Metropolitan Opera, New York

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Opera Archives

The same New York Times review gloomily predicted that the public would not be anxious to see it. However, this couldn’t have been further from the truth: audiences were incredibly eager to hear Smyth’s opera. The opening night of Der Wald was the only night of the year that box office sales at the Metropolitan Opera reached five figures. Among the attendees of the performance was Gardner’s close friend, artist John Singer Sargent.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), Dame Ethel Mary Smyth, 1901. Black chalk on paper, 59.7 x 46 cm (23 1/2 in. x 18 1/8 in.)

National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 3243)

Introduction to Isabella

This interest in Smyth’s music extended to Gardner herself, who was at the cutting edge of the musical developments of her time. Sargent introduced the two women in 1903, during Smyth’s visit to the United States for the US premiere of Der Wald.Gardner invited Smyth to lunch at the Museum, where Smyth gave Gardner the signed photograph now displayed in the Musicians Case.

Aimé Dupont Studio (active New York and Newport, 1886–1950s), Ethel Smyth, 1903. Platinum print, 27.8 x 20 cm (10 15/16 x 7 7/8 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P1w20). Photo: Etta Greer Dupont

The handwritten bars of music Smyth inscribed on the photo are from a climatic moment in Der Wald when a female lead pleads, “Sacred forest, hear our cry!” Gardner was mentioned by name when the newspaper The Sun wrote of Smyth’s visit to Boston and an ultimately unsuccessful petition to bring Der Wald to the city:

In the city of Abigail Adams, Margaret Fuller, Louisa M. Alcott, Julia Ward Howe, Sarah Jewett, Mrs. Ward, Mrs. H. H. A. Beach, Mme. Szumowska and Mrs. Jack Gardner, the woman who wrote an opera was welcomed for her own sake… Boston ought to have Der Wald. If a ‘round robin’ signed by the fairest and best in Boston society can persuade Mr. Grau, Boston will get what it desires.

Her gift to Gardner showed how Smyth advocated for her own work with determination and pride. For her part, Gardner had discerning musical taste as well as a deep interest in musical innovation. Despite the resistance to Smyth’s work at the time, she chose to forever display Smyth’s photo in the Museum. Her decision showed a daring will to commemorate a composer that she felt was important, whatever others thought.

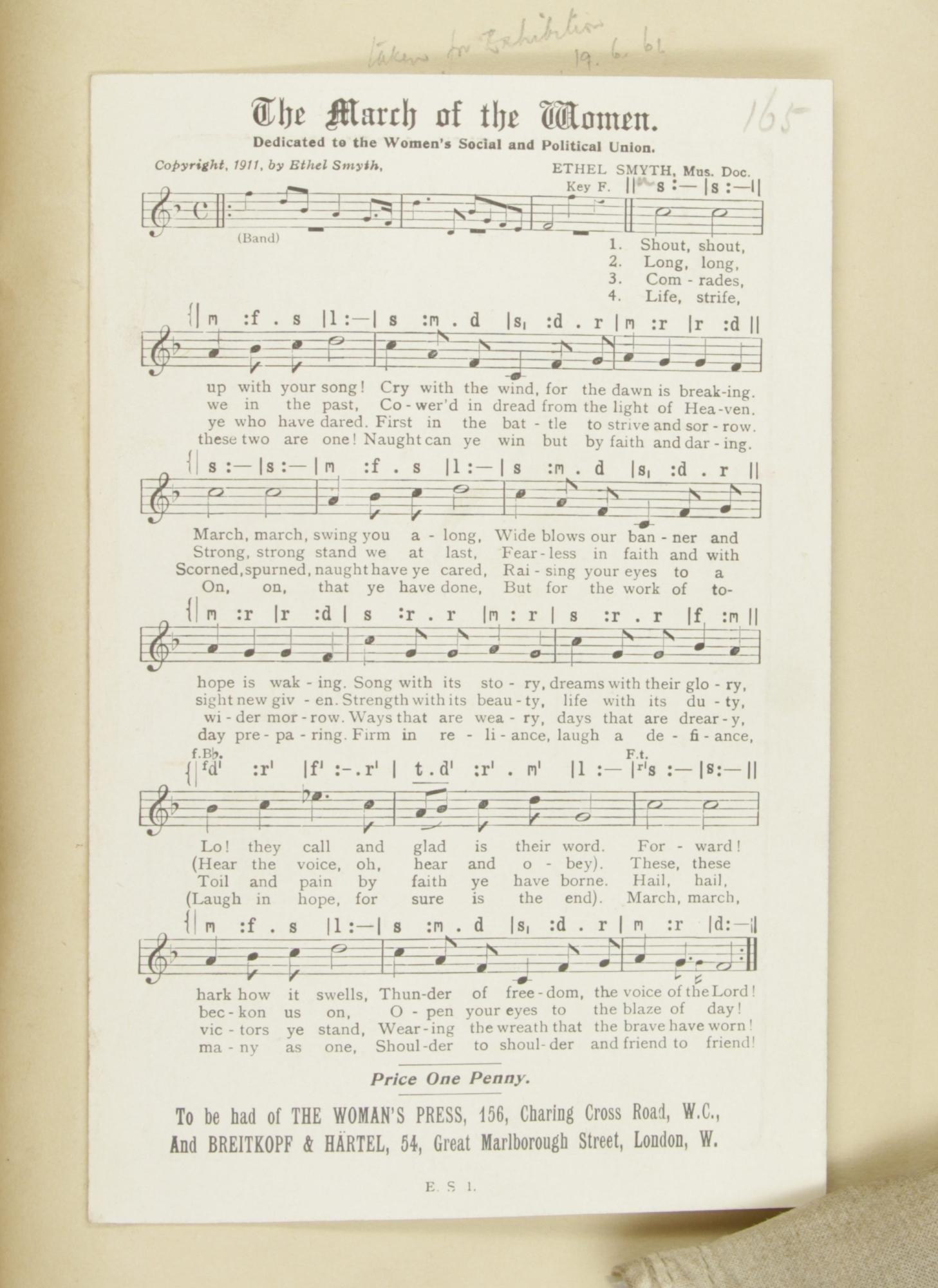

A Suffragette Through Music

Smyth’s strong will and perseverance are evident not only in her career as a composer, but also in her political activity. Smyth was a dedicated suffragette, and her composition “The March of the Women” became the anthem of the women’s suffrage movement. Smyth was even imprisoned for two months for throwing a rock through the window of British politician Lewis Harcourt. The incident happened during a demonstration against politicians who opposed women’s voting rights.

When asked why she broke the window, Smyth said, “The window I selected belonged to the gentleman who said ‘I would not object to women having votes if they were all as intelligent as my wife.’ I think that the most impudent and fatuous thing I ever heard. As if he had the pick of the basket!”

Ethel Smyth, “March of the Women,” 1911.

The British Library, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As both an artist and an activist, Smyth stayed committed to her beliefs and indifferent to the criticism she received. Smyth said about her work, "I care more for the verdict of the people in the galleries than for the opinion of any other public." Her voice echoes Gardner’s intention for her Museum, created “for the education and enjoyment of the public forever.” Both were women who, in different ways, dedicated themselves to bringing art to wide audiences and believed in art’s ability to effect change in the world.

For Smyth, her life as a composer and her political life were deeply entwined, as she expressed when she wrote, “I feel I must fight for [my music] because I want women to turn their minds to big and difficult jobs.” While Smyth’s work has received a resurgence of attention in recent years, works by women composers still only make up 5% of the repertoire performed by orchestras worldwide. Today, Smyth serves as inspiration for a generation of women composers who are striving to change this paradigm.

To hear the work of some of these incredible composers, check out this upcoming concert at the Gardner, whose program features all living women composers.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Julia Ward Howe, BFF and Suffragette

Learn More

Music at the Gardner

Explore the Museum

The Fifteen Cases