On a snowy afternoon several days before Christmas in December of 1902, one hundred students from the Perkins Institute and Massachusetts School for the Blind (now known as Perkins School for the Blind) boarded a street car for Fenway Court, as the museum was known from its founding until Isabella Stewart Gardner’s death in 1924. At Isabella’s invitation, they would be the first audience and also among the first performers in her newly built concert hall known as the Music Room.

Thomas E. Marr and Son (active Boston, 1910–1942), Music Room, Fenway Court, 1914.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

The Perkins School was founded in 1829 by social reformer Samuel Gridley Howe, husband of social reformer and author, Julia Ward Howe. Howe established the school to provide access to education and foster independence for children with blindness. The Arts, and especially music, were critical components of the school’s curriculum. In the early 1900s, students regularly attended music performances in Boston, received singing and instrument instruction, and participated in Orchestra and Glee Club. Isabella’s longtime friendship with Julia Howe and her daughter Maud Howe Elliot most likely influenced the invitation on that snowy afternoon in 1902.

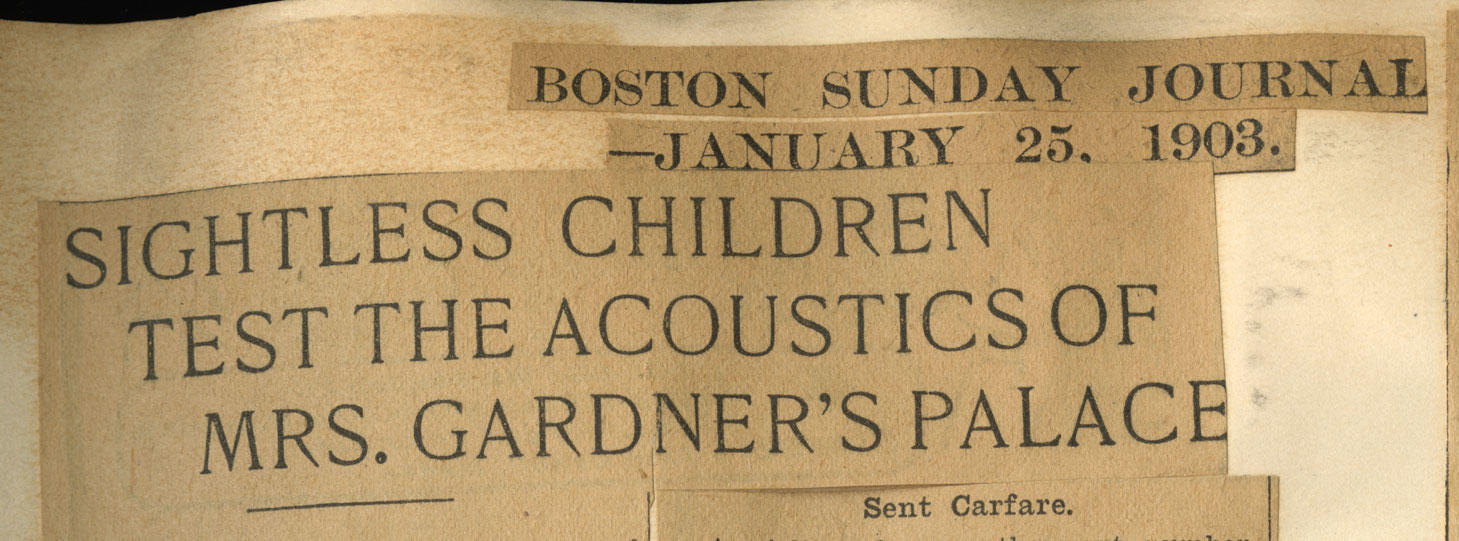

An article titled “SIGHTLESS CHILDREN TEST THE ACOUSTICS OF MRS. GARDNER’S PALACE”¹ ran in the Boston Sunday Journal several days after the students’ visit. The story recounted how the children were invited to sing and attend a concert, which featured a violin performance by a member of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

The headline “Sightless Children Test the Acoustics of Mrs. Gardner’s Palace,” from the Boston Sunday Journal, p. 5, 25 January 1903

Perkins Institution Scrapbook of Clippings Jan. 1903–May 1904, Internet Archive. Courtesy of Perkins School for the Blind Archives

Although we have little information about the performance and cannot confirm if the students sang, it is likely that they heard music that was to be performed at the gala celebration planned for New Year's Day 1903. The celebration featured a concert by members of the Cecilia and the Boston Symphony Orchestra performing music by Bach, Mozart, and Schumann. Isabella wanted to be absolutely sure that the acoustics of the Music Room were conducive to hearing great music—but she also did not want anyone to see inside her still-in-progress museum.

Thomas E. Marr and Son (active Boston, 1910–1942), Courtyard, Fenway Court, 1903.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

After the concert ended, a memorable moment occurred. The student’s galoshes, which had been carefully arranged so that they could be found by touch, were accidentally moved into a pile by a well-meaning staff member, causing chaos when it was time for the children to leave. Reputedly, “In later years Mrs. Gardner used to say that to her the most vivid thing about the opening of the palace was the time she spent that afternoon on her hands and knees pairing rubbers together and trying them on the blind children.”²

Isabella later wrote to Michael Anagnos, Director of the Perkins School, for the names of the students who came to the concert, and sent each child a thank you note and ten cents for their streetcar fare. The Boston Sunday Journal reporter praised the children who refused to divulge any details at all, honoring their promise to keep the event “perfectly secret.”³

While this event may be Gardner’s most notable interaction with the Perkins School, it was far from her only one. New information discovered in the school’s archives has revealed evidence of Isabella’s active involvement and support of the school as a member of the committee to establish the first Kindergarten for the blind. In addition to contributing to the school, Isabella Stewart Gardner served on the institution’s Visiting Committee of Ladies, whose role was to “visit the Kindergarten and consult with the matron on its domestic affairs, and extend towards the children such kind notice and advice that they may deem proper.”⁴ Gardner acted as treasurer of the committee’s Auxiliary Aid Society, which raised funds for the kindergarten’s operating expenses from 1889–1892. She also showed her interest in the achievements of the students by attending the school’s graduation ceremonies.

Girls’ kindergarten classroom at the Kindergarten Department of the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Blind, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, about 1900

Photo: A. H. Folson. Courtesy of Perkins School for the Blind Archives

Continuing this legacy, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum has recently launched an initiative to provide greater access to the museum for visitors who have low or no vision. We are adding visual descriptions for permanent collection objects on the website (Fall 2021), hosting art making through the Access Studio program (Winter 2022), and pre-arranged touch tours. Based on her commitment to the Perkins School, we like to believe that Isabella would certainly approve of these growing initiatives.

*The author would like to thank Jen Hale, Lead Archivist at Perkins School for the Blind, for her generous research support.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Visit the Museum

Accessibility at the Gardner

Read More

History of Music at the Gardner

Explore the Collection

Maison Chapelle Cordonnier (established Paris, 1815), Pair of Purple Satin Slippers, about 1900

¹ “Sightless Children Test the Acoustics of Mrs. Gardner’s Palace,” Boston Sunday Journal, 25 January 1903, p.5. Perkins Institution Scrapbook of Clippings Jan. 1903–May 1904, Internet Archive. Courtesy of Perkins School for the Blind Archive

² Cleveland Amory, The Proper Bostonians, 1947, p.136.

³ Ibid.

⁴ Perkins Institute for the Blind, Fifth Annual Report of The Kindergarten for the Blind, 189, p.ii.