Beginning in 1899, Bostonians—and the national press—spent years watching an enigmatic structure take shape in the Fens. As a journalist wrote in a 1902 article “Mrs. Jack Gardner’s Mysterious Boston Museum” in Frank Leslie’s Weekly, “For more than two years Mrs. Gardner has partially succeeded in keeping from the public the beauties of her Fenway museum. Of late, the truth about the strange pile of brick and glass that has been the [center of attention] for many months, has begun to creep out…”

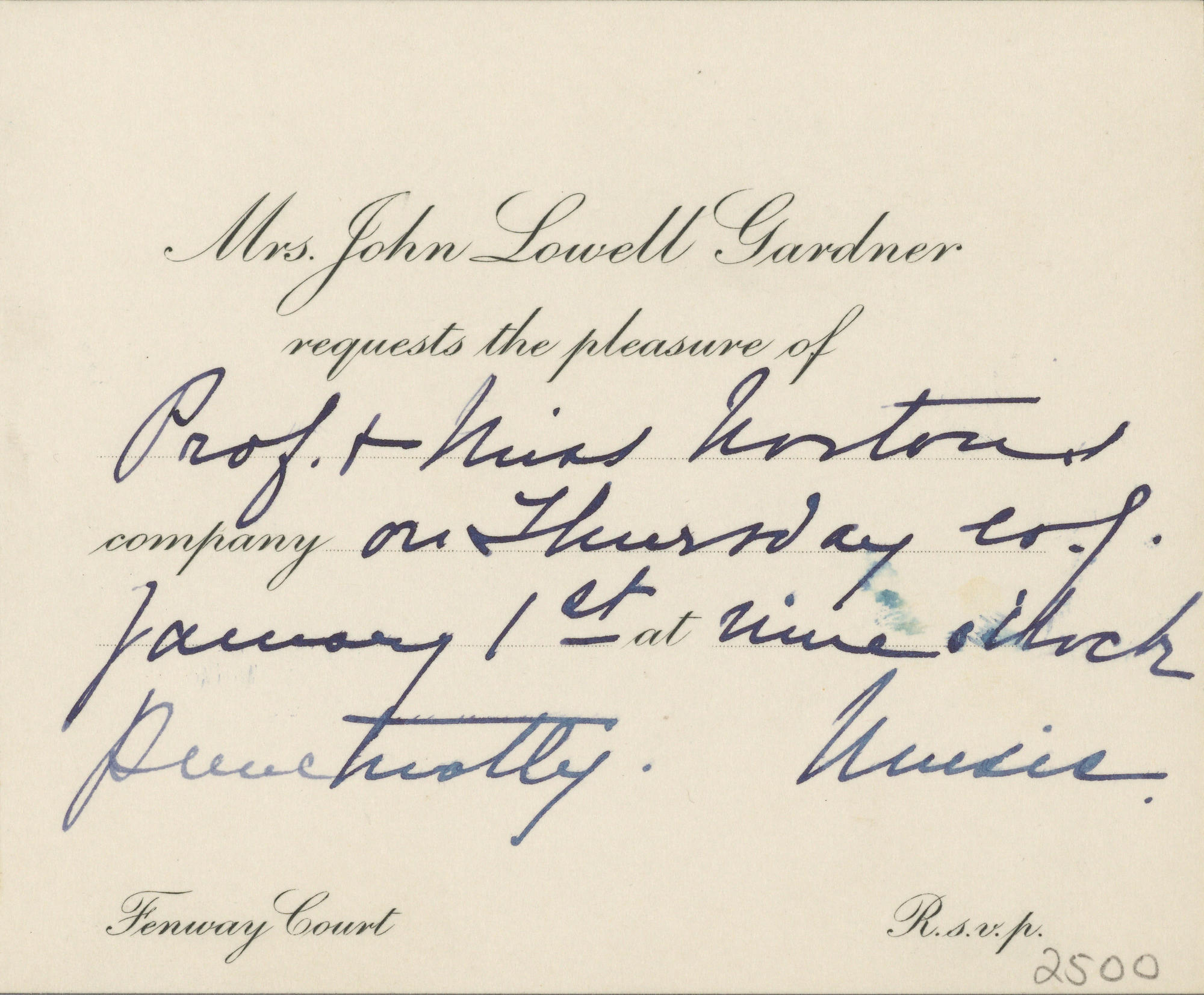

Having successfully kept the secret of what was inside the walls of her Museum, Isabella decided to make a splash when she finally unveiled to the world what she had built. That splash was, unsurprisingly, a lavish party. Invitations were sent to a select group of her friends and acquaintances. They read: “Mrs. John Lowell Gardner requests the pleasure of [your] company on Thursday evening, January 1st, at nine o’clock punctually. Music. Fenway Court. R.S.V.P.” There is an example of one of these invitations preserved in the papers of Isabella’s friend and mentor Charles Eliot Norton.

Invitation to the Opening Celebration for Fenway Court, Charles Eliot Norton Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University

MS Am 1088, MS Am 1088.14, Houghton Library, Harvard University

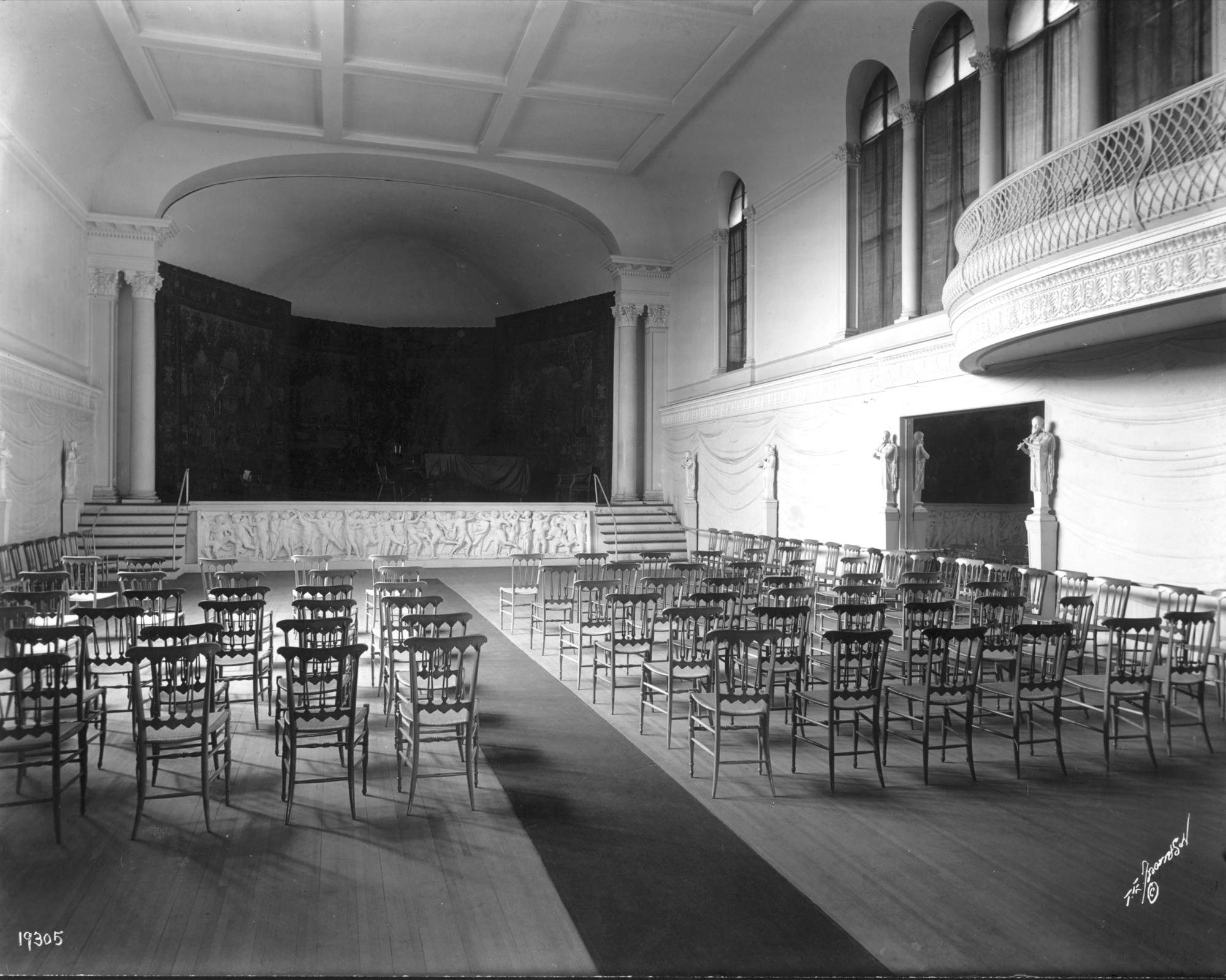

When guests first arrived, Isabella greeted them dressed in a black gown with a cinched waist—as in her iconic portrait by John Singer Sargent—and guided them into what was then the Music Room. (It was later demolished, in 1914, to make way for the Spanish Cloister and Tapestry Room.) There, members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra performed a special concert for the occasion.

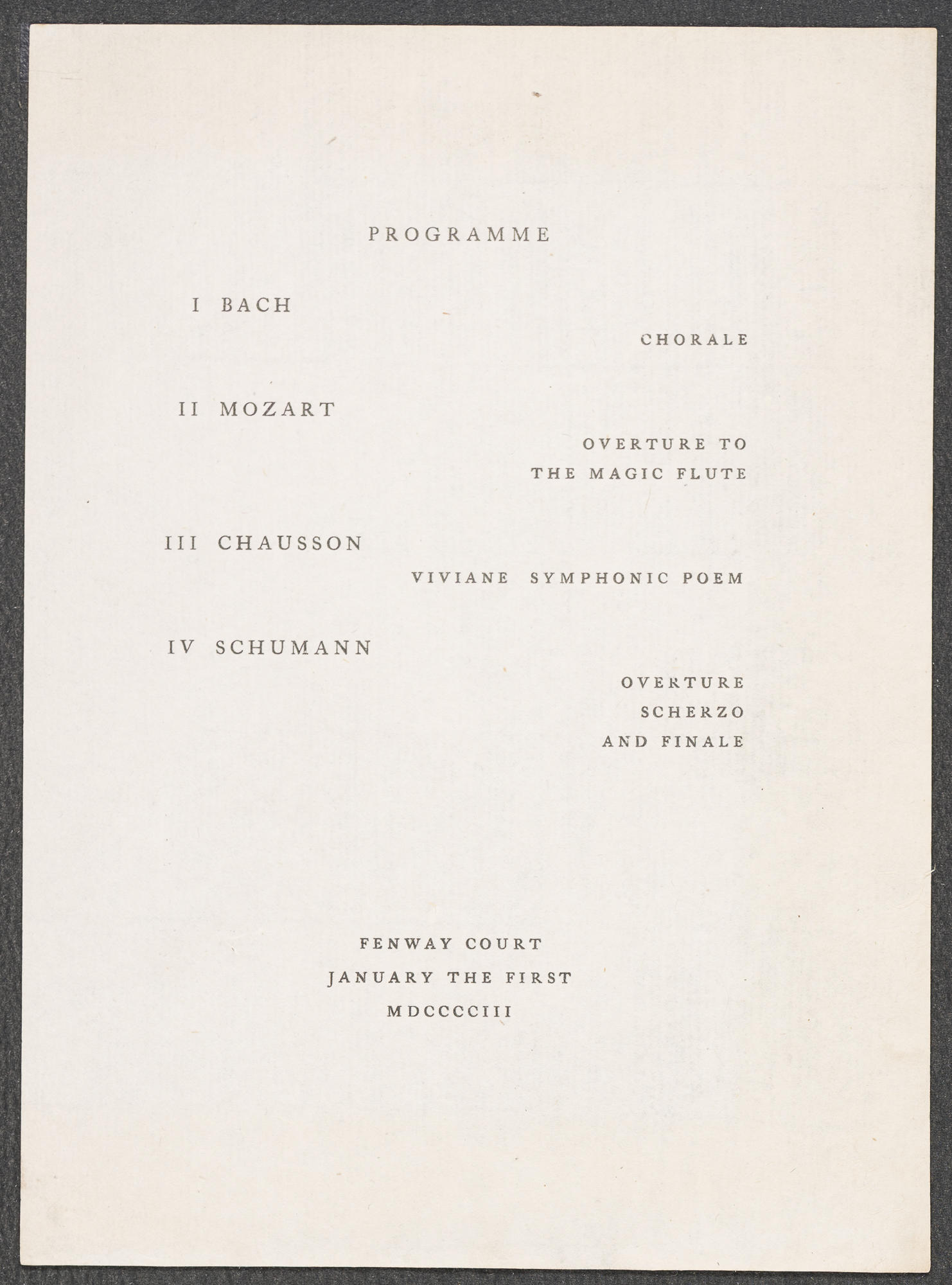

The pieces performed that night are listed on a program preserved in the Museum archives. Isabella’s choice of the overture to Mozart’s fantastical opera The Magic Flute was telling. Choosing music from a work where the main characters travel through a series of gardens, palaces, and temples suggested the wonder of revealing the Palace for the first time.

Concert Program for the Opening of Fenway Court, 1903

Unfortunately, given the state of photographic technology in the early 20th-century—and the fact that the Palace was lit only with paper lanterns on that evening—we do not have any photos from the event. Yet, we do have wonderful descriptions of the evening. Isabella’s biographer Morris Carter described the scene after the musical performance, and quoted the reaction of music critic William F. Apthorp:

A great mirror in one corner of the [Music Room] was rolled back and the guests were admitted to the court[yard]. No one was in the least prepared for the fairy beauty that greeted [their] eyes; even those who had been privileged to see the court before had never seen it like this, and for those to whom it was entirely new it was overwhelming. Here, in the very midst of winter, was ‘a gorgeous vista of blossoming summer gardens . . . with the odor of flowers stealing toward one as though wafted on a southern breeze. There was intense silence for a moment broken only by the water trickling in the fountains; then came a growing murmur of delight, and one by one the guests pressed forward to make sure it was not all a dream.

It’s possible that the Palace may have looked like one of the earliest photographs of the Courtyard, from 1908, seen below. If you look very closely at the photo, you can see there are a handful of paper lanterns hanging under the balconies.

Courtyard, 1908. Thomas E. Marr & Son (active Boston, 1875-1954)

As if all of this were not enough, legend holds that Isabella chose particularly whimsical refreshments: champagne and donuts. The author Edith Wharton was—also according to legend—unimpressed with the choice of food. She thought it was equivalent to what one would eat at a provincial French train station. Nonetheless, Wharton seems to be one of the only people who were underwhelmed by the evening.

While it will be difficult to recreate the wonder of that opening night—and we cannot provide free champagne and donuts to visitors—we are thrilled to welcome guests to the Museum again after a long closure. We can’t wait to see you again in our galleries, and hope you can rediscover the wonder of the Gardner, just as Isabella’s guests did on a cold night in 1903.

You Might Also Like

Come and Visit

Read about the Museum's new reopening protocol

Building Isabella's Museum

Learn about the Museum's construction

Explore the Collection

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925), Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1888