Building Isabella's Museum

You said to me… that if ever you inherited any money that it was yours to dispose of, you would have a house… filled with beautiful pictures and objects of art, for people to come and enjoy. And you have carried out the dream of your youth.

Idea

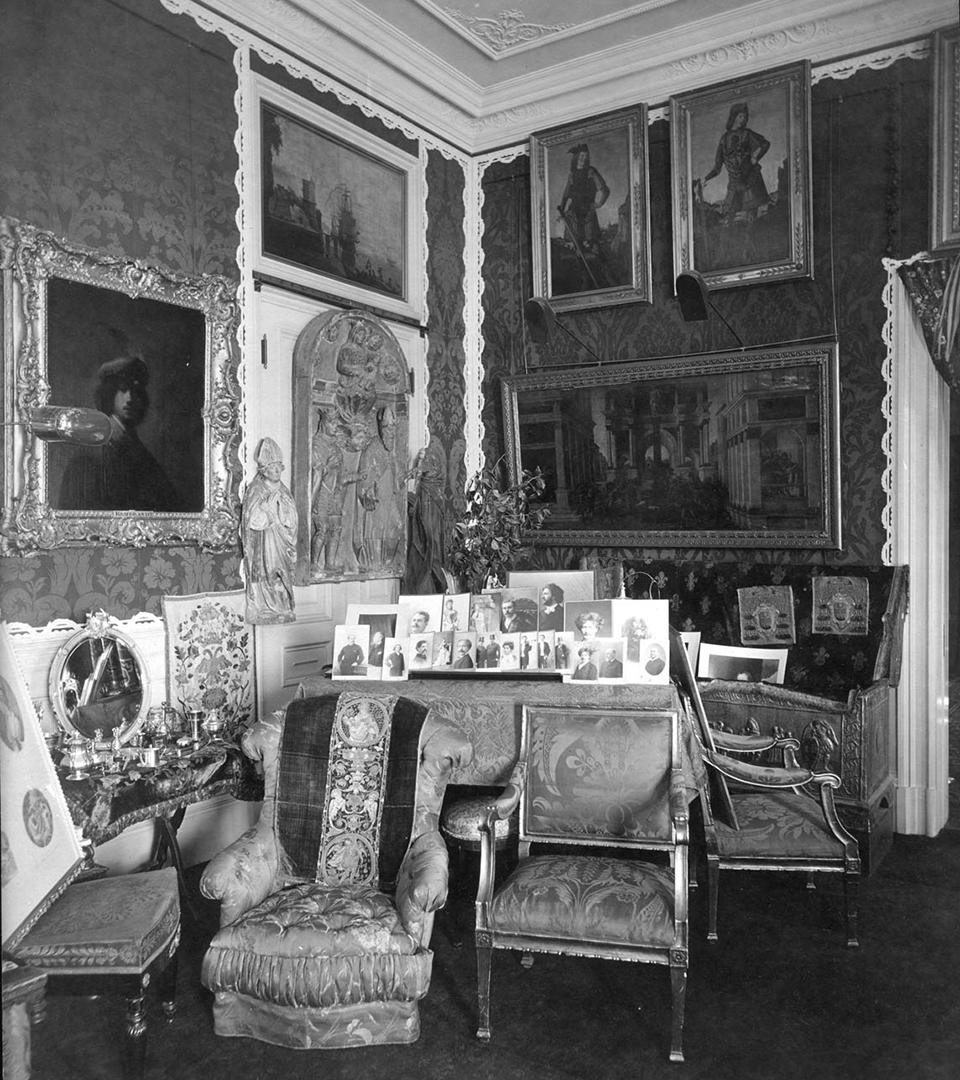

After years of collecting on a small, personal scale, in 1891 Isabella inherited $1.75 million upon her father’s death and was able to begin collecting on a greatly expanded level. Upon purchasing Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait, Age 23 in 1896, Isabella and her husband Jack decided their ambitions as collectors required more space than their residence permitted, and first began to consider the idea of a museum.

The Architect

Isabella and Jack reached out to the architect Willard Sears, who had remodeled their house in Brookline. At first the couple considered expanding their current home, combining two houses on Beacon Street. However, as Isabella’s collection and ambitions continued to grow, Jack felt it would be more sensible to buy land and build a new building for the museum with apartments for themselves within it.

Inspiration

The Gardners loved Italy, and Isabella was especially passionate about Venice, where she and Jack would often stay at the Palazzo Barbaro on the Grand Canal. In the summer of 1897, Isabella and Jack traveled through Venice, Florence, and Rome to gather architectural fragments for their eventual gallery. They purchased columns, windows, and doorways to adorn every floor, as well as reliefs, balustrades, capitals, and statuary from the Roman, Byzantine, Gothic, and Renaissance periods.

The Land

Isabella and Jack were intrigued by the Back Bay Fens, which featured part of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace park system. It is possible that Jack, who was on the board of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), realized the location would eventually be a cultural center (the MFA purchased land in the Fens in 1899), though at the time the newly filled swamp was quite empty. When Jack died suddenly in 1898, Isabella was left to pursue their joint dream on her own.

The Client

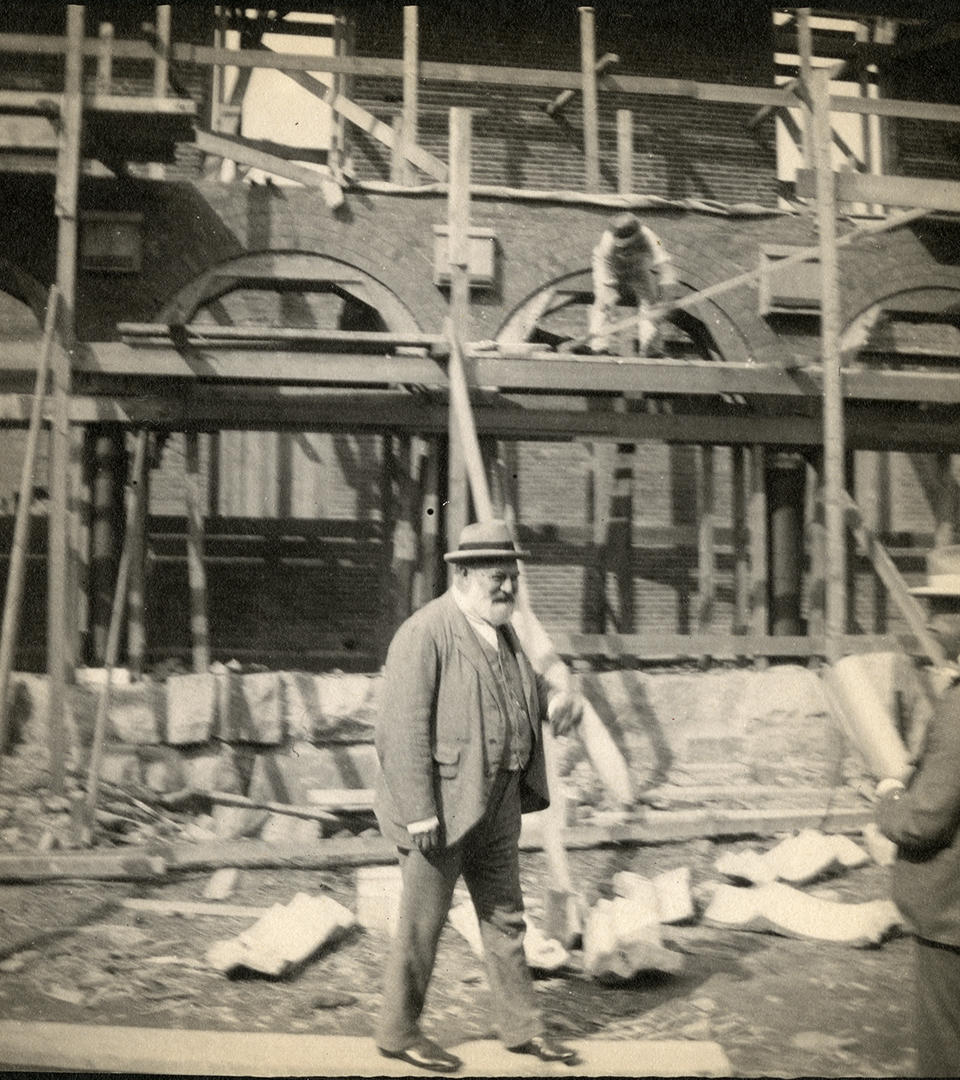

In early 1899, Gardner purchased the land where the Museum now stands, and in June the pile driving began for the building’s foundation. Willard Sears, the hired architect, soon learned that Isabella was a challenging employer and meant to play a more active role than most clients. Throughout construction, she continually made changes, insisting that the workmen undo and redo their work, and Sears had to run interference between Isabella and his workers.

Sears's Diary

Construction

Isabella prided herself on her daily presence at the job site and took a hands-on approach to the work. As she said in a letter, “I still go daily, dinner pail in hand to my Fenway Court work.” Photographs show Isabella standing on a ladder in the Courtyard, demonstrating to the plasterers the effect she sought in the distinctive mottled pink stucco walls. When ceiling beams arrived for the Gothic Room and were too smooth for her liking, she took an ax in hand and hacked away at them to achieve her desired result.

Design Genius

As much as any single work of art within the Museum, most visitors take away the experience of the Courtyard, where the stonework arches, columns, and walls create an unforgettable impression. By integrating Roman, Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance elements and stone columns, she could have created a discordant mess. Instead, it is a beautiful and harmonious whole.

…the Gardner is more remarkable than it looks at first. This is a palace that has been turned inside out… The Gardner’s real facades are the four sides of the atrium… And these mottled indoor facades are washed by sunlight that is modulated… in such a way that it often resembles light reflected off water, as it would be in Venice.

Collection

Construction of the Museum was mostly completed by late 1901. Gardner moved into the private fourth-floor living quarters and devoted herself to personally arranging works of art in the galleries on the first three floors. In 1902, Isabella installed her collection of paintings, sculptures, tapestries, furniture, manuscripts, rare books, and decorative arts. She continued to acquire works and change the installations for the rest of her life.

… downstairs, I feel, are all those glories I could go and look at, if I wanted to! Think of that. I can see that Europa, that Rembrandt, that Bonifazio, that Velazquez et al. — any time I want to. That’s richness for you.

Learn More

Isabella Stewart Gardner

Discover the life of Isabella

New Meets Old

How the glass-enclosed New Wing, designed by architect Renzo Piano, plays off Isabella’s Venetian-inspired palazzo

The Collection

Explore Isabella's Collection