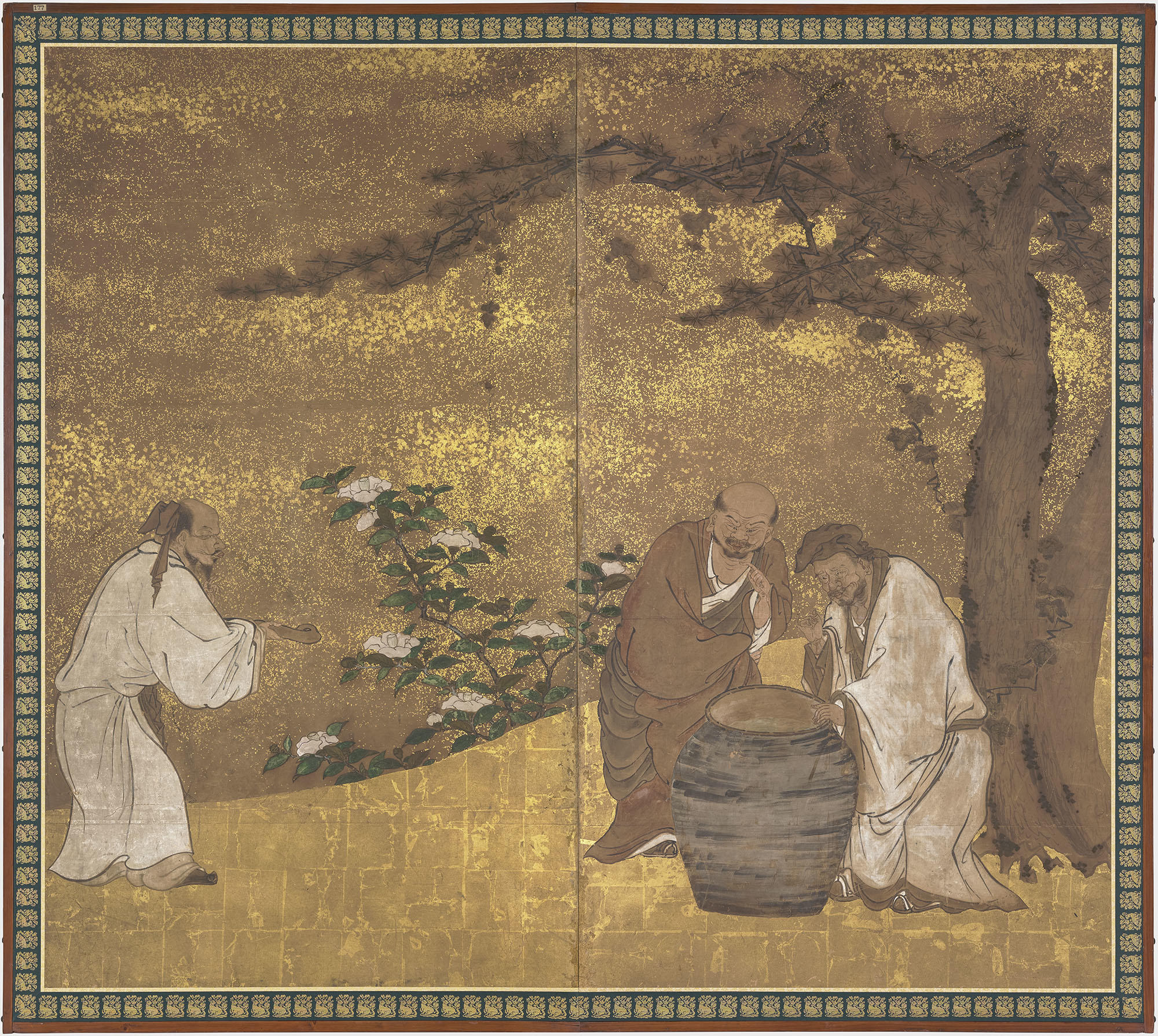

Displayed in the Second Floor Passage of the Gardner Museum, a charming and skillfully painted Japanese two-panel folding screen depicts the Three Vinegar Tasters (sansanzu 三酸図), a beloved theme among Zen painters. It takes as its subject a legendary episode involving three figures famous in Chinese cultural history: the poet Tao Yuanming (365–427), the Daoist scholar Lu Xiujing (406–477), and the Buddhist monk Huiyuan (334–416). According to the legend, while spending a relaxing afternoon together in the garden of Huiyan’s temple, the three friends drank from an old pot of wine so aged it had turned to vinegar. Shocked by the sour flavor, they were at once jolted awake from their reverie. The three men were later identified as avatars of the three great teachers Confucius, Laozi, and the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni. Their vinegar experience was understood to exemplify the so-called Unity of the Three Creeds—Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism: vinegar tastes alike to all practitioners regardless of individual teachings and beliefs. And life and its experiences, like the sour taste of vinegar, is common to adherents of all creeds.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P20e2). See it in the Second Floor Passage.

Japanese, Kano School, The Vinegar Tasters, early 17th century. Ink, mineral pigment, and gold leaf on paper, 167 x 187 cm (65 3/4 x 73 5/8 in.)

The idea of the Unity of the Three Creeds first emerged in late-eleventh century China among a socio-cultural group of men committed to the ancient ideal of the gentleman scholar (wenjen 文人). For these men, the amateur artist (poet-calligrapher-painter-scholar-musician) embodied the highest of all human attainments. Paintings of the theme of the Unity of the Three Creeds, which includes the Three Laughters of Tiger Ravine and the Patriarchs of the Three Creeds, “express the principle of the fundamental unity of man, nature, and society and of political-ethical, religious, and artistic concerns. It is a principle that dissolves the boundaries between the sacred and the profane, the self and the non-self, the animate and the inanimate, the beautiful and the ugly, between social classes and between nations.”1

Not only does the theme of the Gardner screen originate in China, so too does the style of painting it employs. The fluid, calligraphic lines that showcase the hand of the artist reflect an approach to painting that flourished among Chan (the Chinese word for Zen) monastic communities of the Song dynasty (960–1279). The large pine tree, curving in and out of the composition, its angular branches guiding the viewer to the figures below, is a common motif found in both Chan painting and in painting of the Southern Song imperial court (1127–1279). However, the folding screen painting format and the application of the gold leaf ground place this work squarely in the hands of a Japanese painter.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ex. coll.: C.C. Wang Family, Gift of The Dillon Fund, 1973 (1973.120.9)

Ma Yuan (Chinese, active about 1190-1225), Scholar Viewing a Waterfall, early 13th century. Album leaf; ink and color on silk, 25.1 x 26 cm (9 7/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

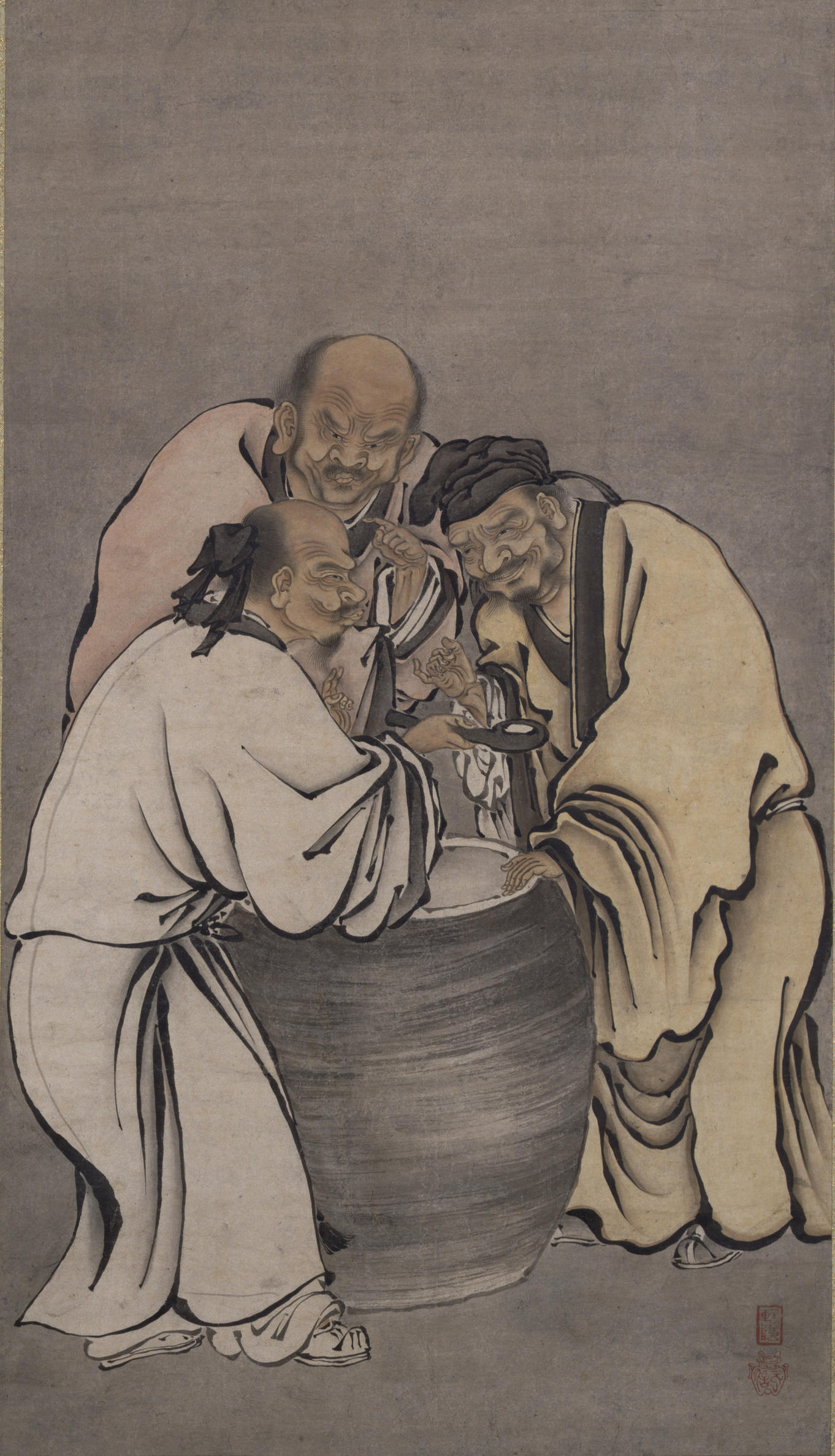

Painted in the seventeenth century by an artist of the Kano school, the official painting house of Japan’s military rulers, famous for its mastery of Chinese pictorial modes, the figures in the Gardner screen bear close resemblance to those portrayed in a hanging scroll of the same subject attributed to Kano Motonobu (1476–1559), the second-generation head of the Kano school.

National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan

Attributed to Kano Motonobu (Japanese, 1476–1559), The Three Vinegar Tasters, Muromachi period, 16th century. Hanging scroll, ink and light color on paper, 83.3 x 47.5 cm (33 x 19 in.).

The pose and position of the two figures standing near the pot, as well as the profile view and hand positions of the figure on the left, including the way his two raised fingers are visible through his pointed goatee, indicate the artist of the Gardner screen has closely followed Motonobu’s model, modifying it to suit the larger painting format. This kind of modification and adaptation of a master’s work was common practice in Kano painting workshops, which grew at such a rapid pace over the course of the Edo period (1615–1868; by the early eighteenth century, there were twenty Kano studios active in the city of Edo alone) that a strict training curriculum based on the study of a corpus of model paintings (funpon 粉本) was implemented. Young apprentices were required to copy this body of painting models, memorizing brush modes and compositions, thus ensuring artistic continuity and consistency in the works produced by Kano trained painters.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P20e2)

Detail of The Vinegar Tasters, early 17th century, showing Tao Yuanming and Huiyuan

Little is known about the painting’s provenance prior to its acquisition by Isabella at an auction held by art dealer Matsuki Bunkio in 1901. The size of the screen’s panels suggests they may once have been mounted as sliding doors (fusuma 襖), perhaps in the rooms of a Zen temple, where they would have been part of a large suite of Chinese figures. Kano school artists were often commissioned to paint the interiors of Zen temples, and they frequently portrayed Chinese figural themes including the Unity of the Three Creeds. And that creates a delightful irony in the history of this painting. As already mentioned, the theme belongs to the lineage of ideas of eleventh century gentleman scholars from China who aspired to the ideal of the amateur artist-philosopher, for whom painting was not about formal likeness or technical skill but about capturing the essence of the subject. Such ideas were diametrically opposed to those of the professionally trained Kano school artists working from copybooks. Such an artist, in the gentleman scholar’s view, could never understand nor capture the depth and complexity of the Unity of the Three Creeds. Yet here we have the Gardner screen, as well as the many Kano masterpieces, proving them wrong.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Isabella’s Reliquary of Friendship

Read More on the Blog

Isabella’s 1883 Japan Travel Albums

Learn about Artists Inspired by the Collection

Raqs Media Collective

1John Rosenfield, “The Unity of the Three Creeds: A Theme in Japanese Ink Painting of the Fifteenth Century,” in Japan in the Muromachi Age, ed. John Whitney Hall and Toyoda Takeshi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 207.