In the impressive collection of Japanese art housed in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, there is a particular stand-out piece: a miniature pagoda. The pagoda is notable neither for its beauty nor because it would break auction records, but rather for how it encompasses sentiments about sacred art, history, and friendship. This small pagoda represents the Buddha, an eighth-century empress’s act of piety, and above all, the history of Japanese art in North America and the intimate bond between Isabella and the Japanese art historian, Okakura Kakuzō (1863-1913).

The Gardner pagoda is a replica of one of the One Million Pagodas, the Hyakumantō, commissioned by Empress Shōtoku (718-770) as an offer of thanks to the Buddhas for aiding in the suppression of the Emi Rebellion of 764. A total of one million pagodas were distributed equally among ten major temples in the Nara region of Japan. Composed of a three-storied body and seven-ringed finial crowned by a wish-fulfilling jewel, the Gardner pagoda itself is a replica and was carved from wood taken from Hōryūji, a temple that received 100,000 of Empress Shōtoku’s Hyakumantō, each containing a sheet of paper block-printed with one of four prayers from the Mukujōkōdarani Sutra. Of the ten Nara temples to receive the empress’s offering, Hōryūji was the only one to maintain its collection into the modern period.

A pagoda is a reliquary that contains the Buddha’s relics. To worship at a pagoda is to experience proximity to the Buddha and to be in the presence of his charismatic essence. The relics contained in a pagoda are typically material, including purported bone fragments from the historical Buddha’s cremation, or objects or clothes touched and used by the Buddha, a disciple, or a great Buddhist teacher. Pagoda relics can also be textual, in the form of a sutra (the recorded teachings of the Buddha).

© UNESCO

Vesna Vujicic-Lugassy, Buddhist Monuments in the Horyu-ji Area, 2012

A Sacred Pagoda Reincarnated

The pagoda replica in the Gardner museum was carved around 1922 by Niiro Chūnosuke (1869-1954), who was the pupil and successor of the esteemed scholar and art critic, Okakura. In charge of repairing national treasures in Nara, Niiro would have encountered Hōryūji’s Hyakumantō and likely carved Isabella’s pagoda inspired by one of these authentic models. Niiro’s elevated position would have enabled him to use Hōryūji’s sacred wood for the pagoda.

Niiro and Isabella met in Boston in 1909 when, at Okakura’s recommendation, Niiro was hired to repair the Buddhist sculptures at the MFA and to assist with the installation of its new East Asian Galleries. Okakura wrote to Isabella to inform her of Niiro’s arrival:

Niiro a young sculptor and a connoisseur is to accompany Frank back to Boston. Niiro is to be engaged in the work of installation at the Museum for a year. He is a fine, clean man and I recommend him to your good graces.

Always warm and generous to Okakura’s friends and associates, Isabella would have welcomed Niiro into her home and invited him into her circle of Boston elites and intelligentsia.

The British Museum (1932,0309.1). © The Trustees of the British Museum

Niiro Chūnosuke (Japanese, 1869 - 1954), Replica of Bodhisattva Kudara Kwannon figure, 1931-1932. Painted wood, bronze, 3.10 metres (total height)

A Beautiful Friendship

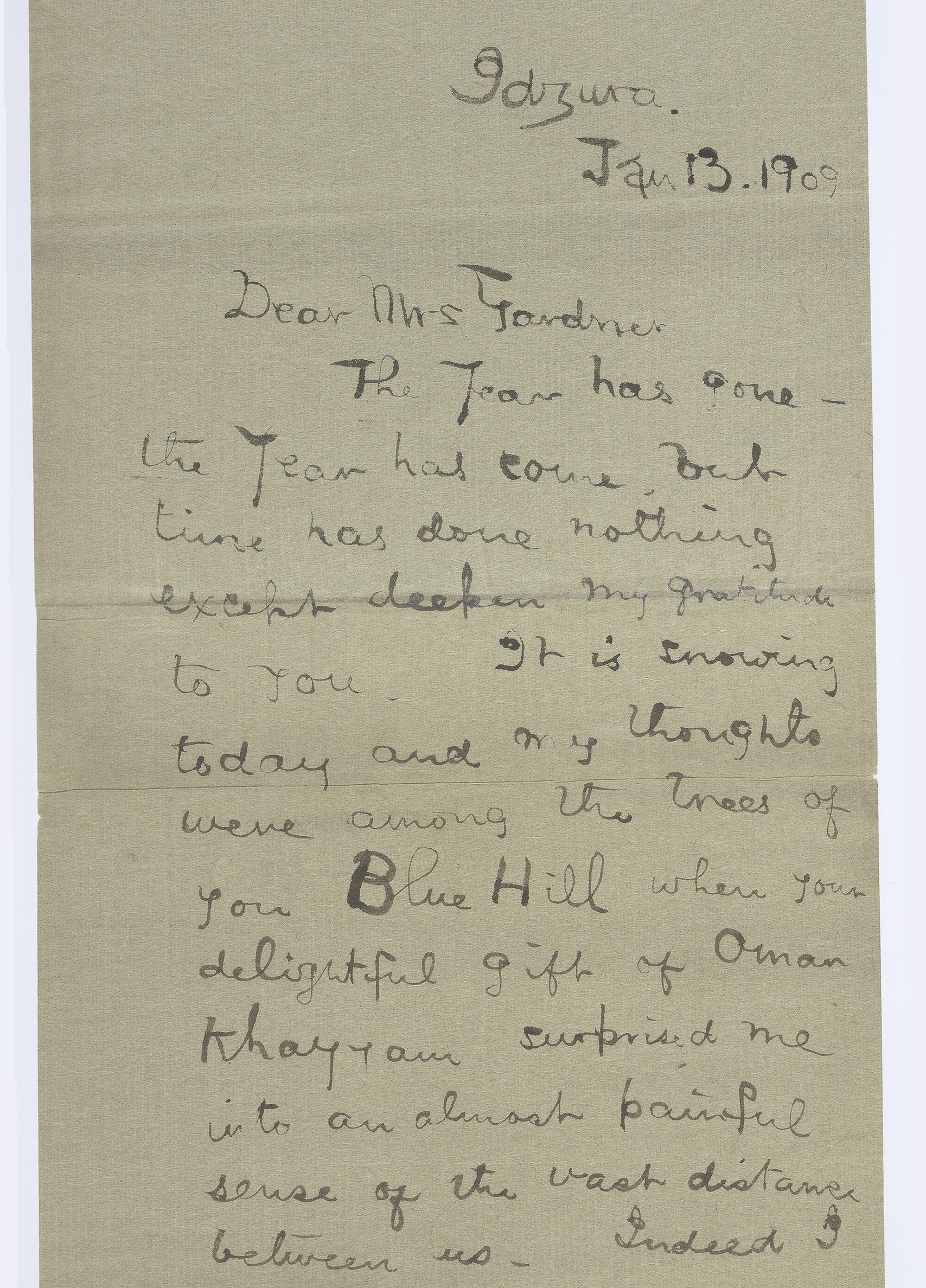

Niiro’s mentor, Okakura, met Isabella in Boston in 1904. Though Isabella was 22 years Okakura’s senior, they shared a love for music, literature, art, and travel and became instant friends. Over the course of less than a decade, a remarkably deep friendship grew between them, evident in the many gifts, letters, and poems they exchanged and in the recollections of those around them. In a letter from Japan, dated January 13, 1909 and written on a scroll of paper, Okakura laments the distance between them:

It is snowing today and my thoughts were among the trees of you[r] Blue Hill [Green Hill] when your delightful gift of Omar Khayyam surprised me into an almost painful sense of the vast distance between us—Indeed I wish I were this moment in your presence and regret that some time must pass before I see myself in Boston again.

In another letter from Japan, written on New Year’s Day, 1910, he writes “I often yearn to be there without reason—perhaps with very good reason.”

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.004124)

Okakura Kakuzō (Japanese, 1862 - 1913), Letter to Isabella Stewart Gardner from Idzura [Izura], Japan (detail), 13 January 1909. Ink on paper

According to Isabella’s friends, she too suffered whenever Okakura left for Japan. In a letter from 1908 to the art historian and her art advisor Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), she wrote:

“Okakura has gone, which I mourn daily.”1 In 1911, she wrote to a friend: “Okakura goes in August back to Japan and that will be a grief,” and “Okakura goes back to Japan tomorrow and I shall be in the dumps.”2

A Sudden Tragedy

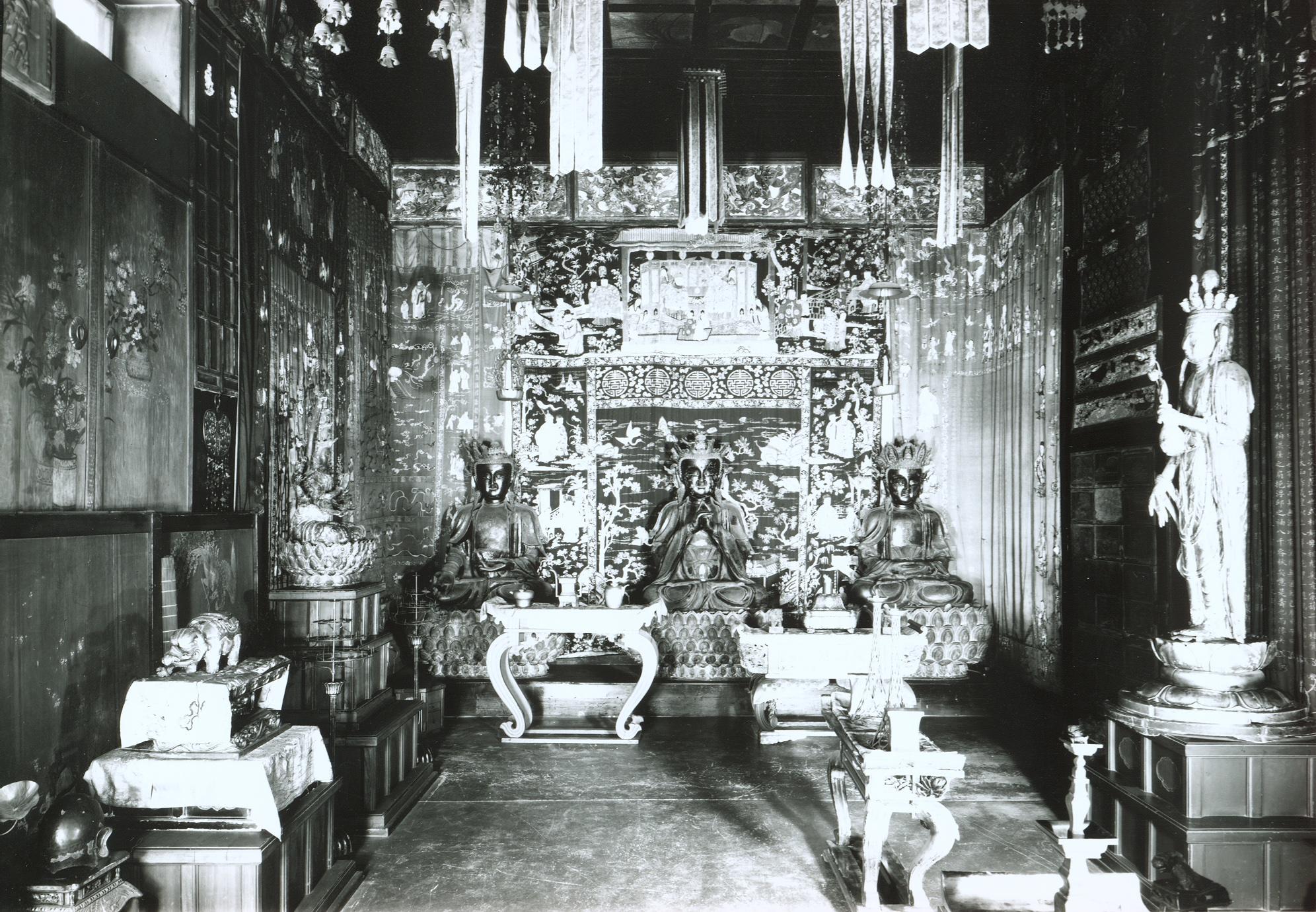

Sadly, Okakura’s untimely death at the age of 50 left Isabella grief-stricken and devastated. Okakura died on September 2, 1913, and it came as a great shock to Isabella. On October 20th, she held a memorial service for him in the now-demolished Music Room of her museum. A Buddha sculpture was moved to the room for the occasion and encircled with candles and incense. After his death, Isabella permanently closed the Chinese Room of her museum, a room that had been filled from floor to ceiling with an assortment of Chinese, Japanese, and Western objects, and transformed it into a private and somber temple-like space to honor the memory of Okakura, whom she believed had made her a better person.3

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Chinese Room, 1961.

Isabella's friendship with Okakura changed her perspective on life. In a letter recounting a conversation with Isabella from January 1914, Mary Berenson (1864-1945) wrote that Isabella had wept and said, “…perhaps she would have gone to her grave with her hard heart and selfish character if it had not been for a Japanese mystic named Okakura…He was the first person, she said, who showed her how hateful she was, and from him she learnt her first lesson of seeking to love instead of to be loved. She admitted that many of her bad habits remained, but said that the core of herself was quite different, and she wanted to get rid of old evils.” 4

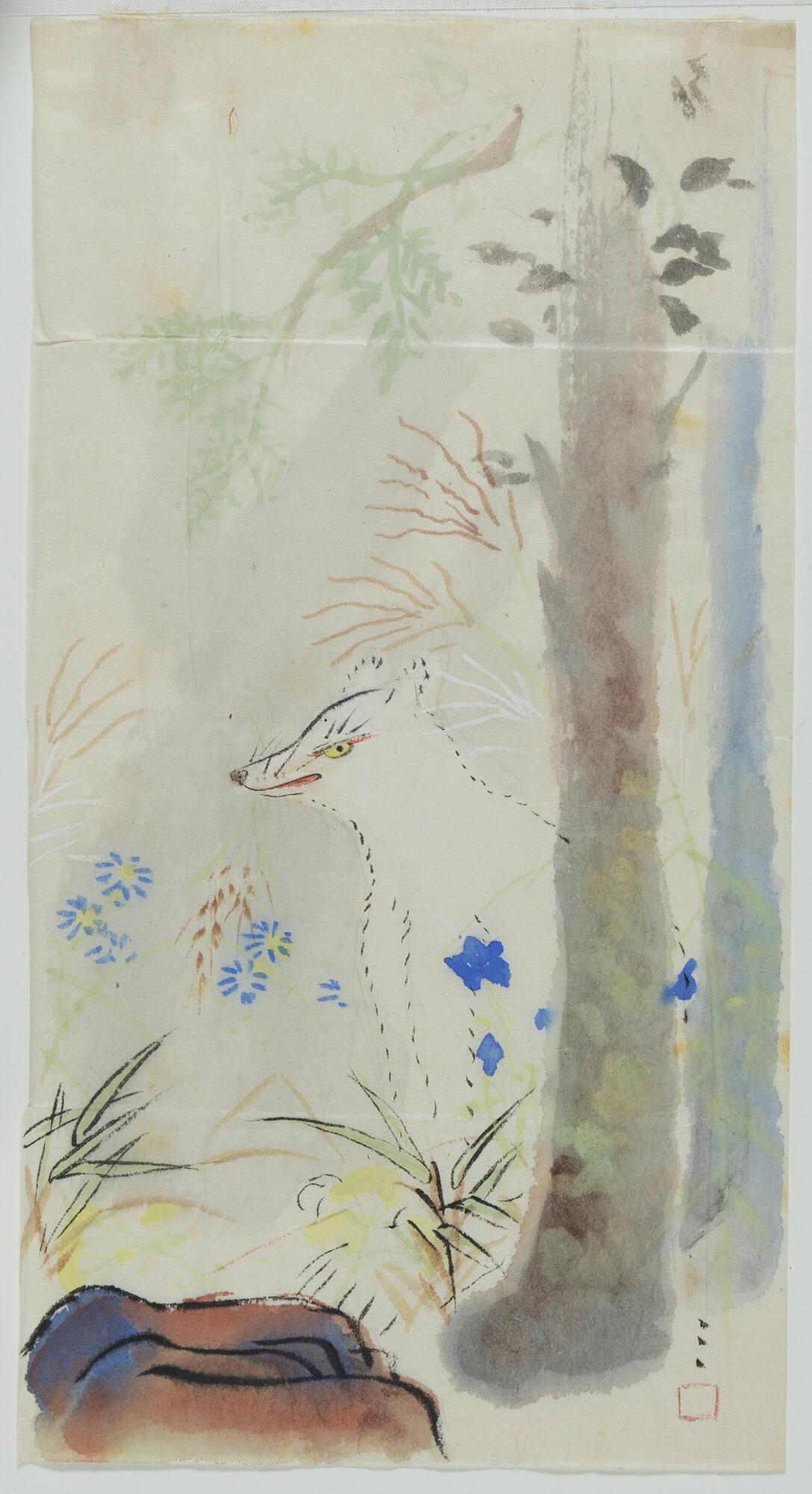

By some accounts Isabella never recovered from the loss. Those around her felt the depth of her mourning and tried to bring her solace. Several works in the Gardner collection are gifts Okakura had given to others, which were then sent to Isabella after his death For example, Denman Ross (1853-1935) sent a lunch box and teacups, and Okakura Yoshisaburo (1868-1936) gifted a drawing of a white fox by Shimomura Kanzan (1873-1930). 5

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P3n20)

Shimomura Kanzan (Japanese, 1873 - 1930), White Fox, about 1913. Watercolor on paper, 29 x 16 cm (11 7/16 x 6 5/16 in.)

A Sacred Gesture

The pagoda was given to Isabella on June 25, 1924—one month before she died. The gift was delivered to the bedridden Isabella by Tomita Kojiro (1890-1976), the longtime curator of Asian art at the MFA Boston and close associate of the late Okakura. The symbolic significance and timing of such a gift are telling.

As Isabella neared the end of her life, Tomita and his wife had recently returned from Japan, where they likely met with Niiro and received the pagoda for Isabella. A particularly moving detail about this deathbed gift is that Tomita and his wife filled the pagoda’s interior cavity with plum blossom petals they collected from Okakura’s grave.

Tomita and his wife were surely aware of the poetic and spiritual significance of filling a pagoda with plum blossom petals from Okakura’s final resting place. Bringing the pagoda to Isabella’s bedside, where she lay critically ill, their intention was likely to offer comfort in the final days of her life by reuniting her with her cherished friend.

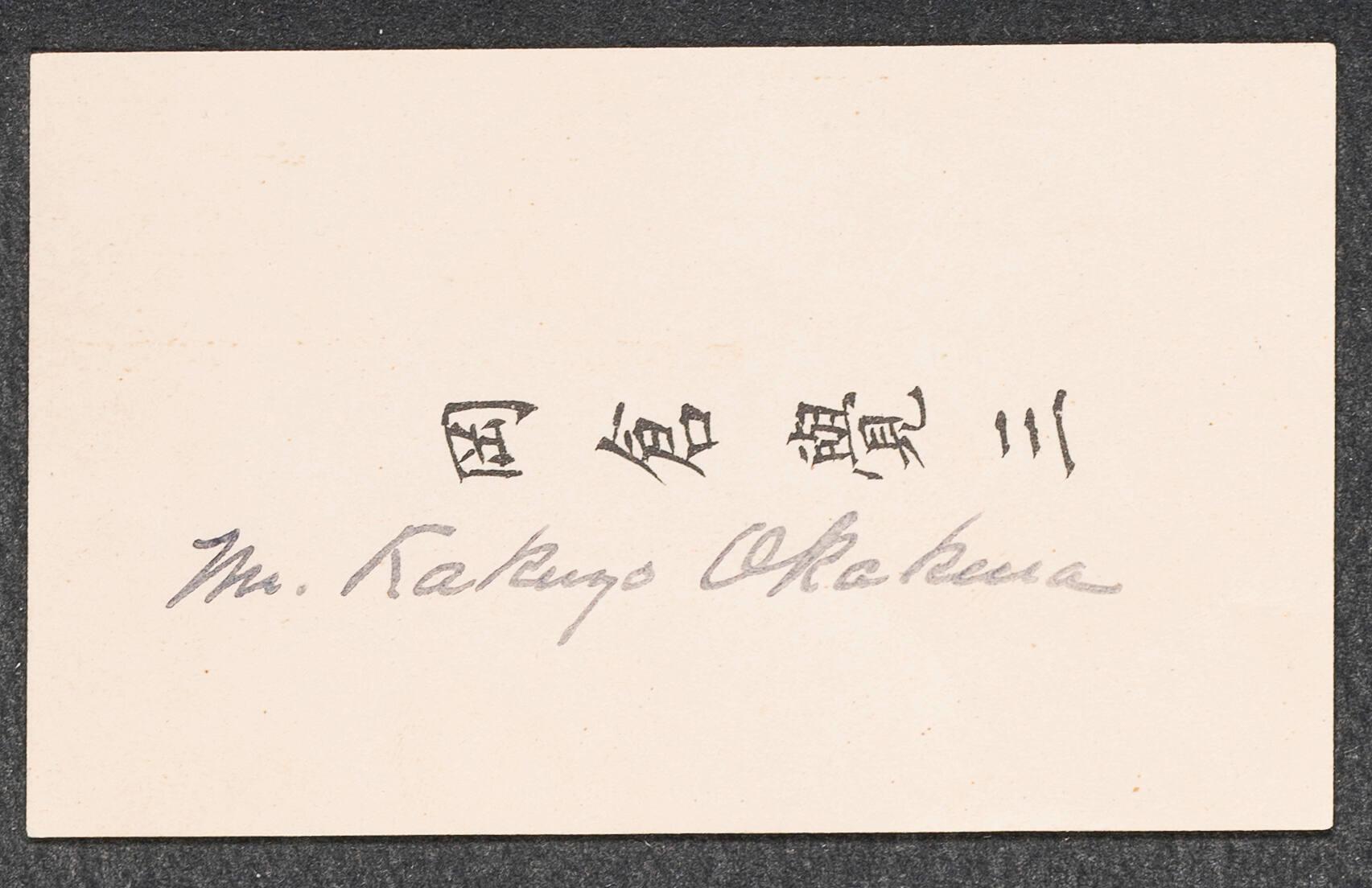

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.004141)

Okakura Kakuzō (Japanese, 1862 - 1913), Visiting Card, 13 March 1904. Ink on card stock.

I would like to imagine that Niiro and Tomita came together to create a gift for Isabella that would celebrate and memorialize their mutual friend and mentor, Okakura. Perhaps they were precipitated by the knowledge that Isabella's health was rapidly declining after she suffered the first of a series of strokes in 1919. Perhaps they agreed on the appropriateness of borrowing the Hyakumantō’s form and using Hōryūji’s wood to commemorate Okakura’s extraordinary contributions to the field of Japanese art history and his active role in preserving Japan’s Buddhist treasures in the wake of a nationalist movement that sought to eradicate Buddhism from the country. I imagine Niiro and Tomita exchanging ideas for how to fill the pagoda’s interior, agreeing on the poignancy of plum blossom petals collected from Okakura’s grave which, like objects touched and used by the Buddha, may serve as relics of Okakura himself. In this way, the pagoda becomes a kind of substitute body for Okakura, an extension of him that could be transported to Isabella’s bedside.

The historical breadth and emotional depth of the gift, the tender thoughtfulness of it, reflects Isabella’s impact on those around her and the remarkable bond of friendship between her and Okakura.

Read More on the Blog

Isabella and Okakura Kakuzō’s Impactful Friendship

Read More on the Blog

From Tree Sap to Tea Jar: East Asian Lacquer

Gift at the Gardner

Mona Higuchi: Bamboo Echoes

1 Victoria Weston, East Meets West: Isabella Stewart Gardner and Okakura Kakuzō (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1993), 32.

2Ibid.

3Ibid., 33-34.

4Alan Chong and Noriko Murai, Journeys East: Isabella Stewart Gardner and Asia (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2009), 36.

5Chong and Murai, Journeys East, 35-36.