"You must let me tell you this moment while the ‘glow’ is upon me, that I never saw anything so daring, so splendid, so really great as your portrait. It is first, great as a likeness, after that it is everything enthralling. . . . A mysterious + awful power is in that same Mr. Sargent." —Frances Morse Lang to Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1888

"What does it matter if Mr. Sargent . . . makes a dowdy look like a queen . . . a little insignificant woman . . . gives the air of a goddess if no one can recognize in the picture the features of the original?" —The Art Amateur (1888)

A Byzantine Madonna with a halo.

"Sargent had painted Mrs. Gardner all the way down to Crawford’s Notch." —Rumored anonymous comment about the portrait, according to the biography Mrs. Jack (1965) by Louise Hall Tharp

All of these comments were made about John Singer Sargent’s Isabella Stewart Gardner (1888), which usually presides over the Gothic Room. However, in the fall of 2023, it is displayed in the Gardner Museum’s New Wing as part of the exhibition Inventing Isabella. The quotes excerpted here represent the range of reactions at the time: critical, praising, reassuring, and scandalized. This flurry of responses was likely what Gardner sought when she hired the young and relatively little-known—at least in the United States—American artist John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) to paint her portrait.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P30w1)

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1888. Oil on canvas, 190 x 80 cm (74 13/16 x 31 1/2 in.)

Connecting With John Singer Sargent

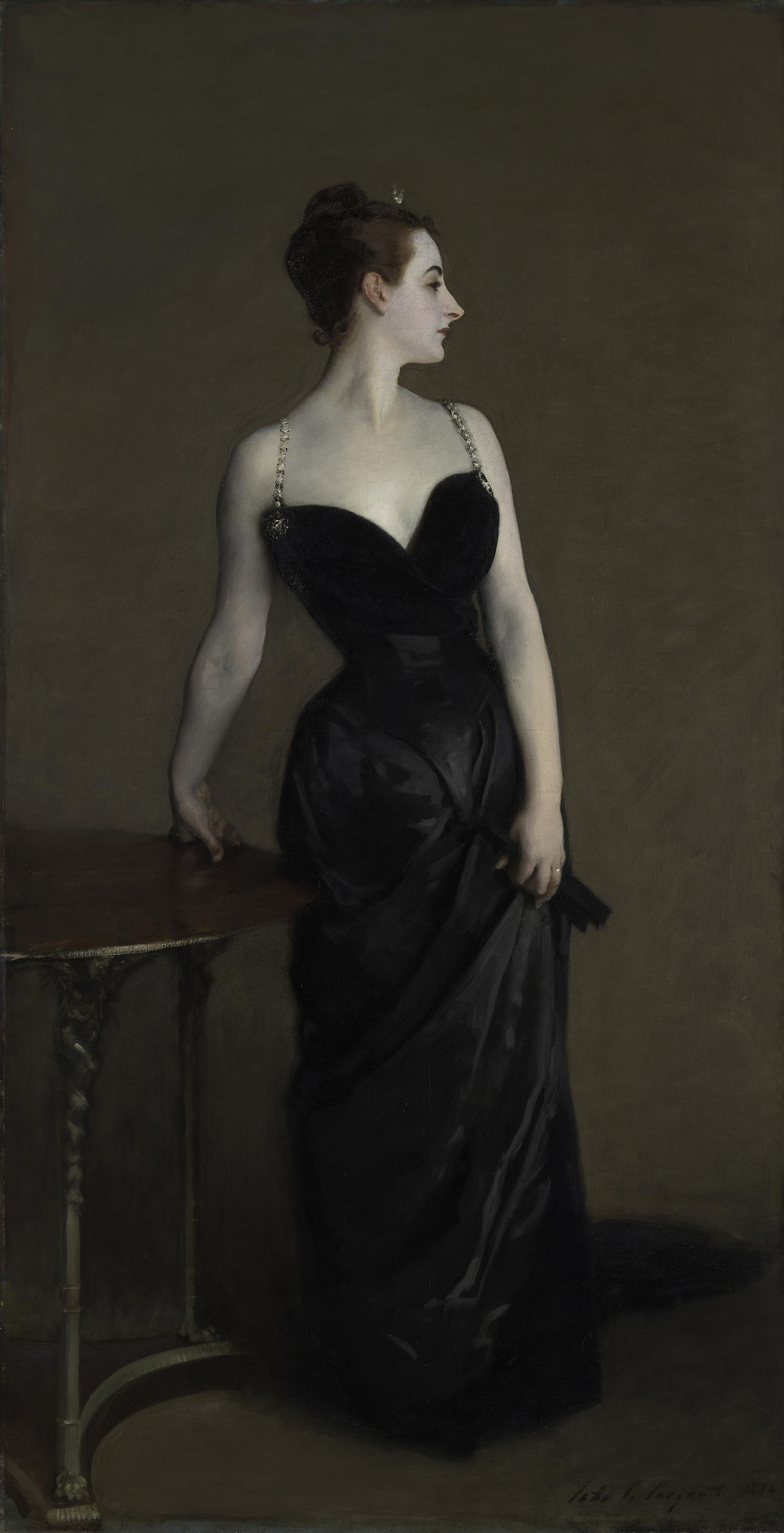

In 1886, Gardner was determined to meet Sargent. The painter had recently settled in London, retreating from the critical reception of his sensuous likeness of a beautiful American in Paris, Madame X (exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston as part of the special exhibition Fashioned by Sargent, October 8, 2023–January 15, 2024). The negative critical and social response to that daring portrait jeopardized the young artist’s career and encouraged him to leave his longtime home in the French capital.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (16.53). Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), 1883–1884. Oil on canvas, 82 1/8 x 43 1/4in. (208.6 x 109.9cm)

Rather than avoid this controversy, Gardner sought it out. With an introduction from her friend Henry James, she saw the notorious painting in Sargent’s London studio and soon commissioned him to paint her portrait. Though Sargent would quickly become the portraitist of choice for American elites, this was a relatively early commission from a client in the United States.

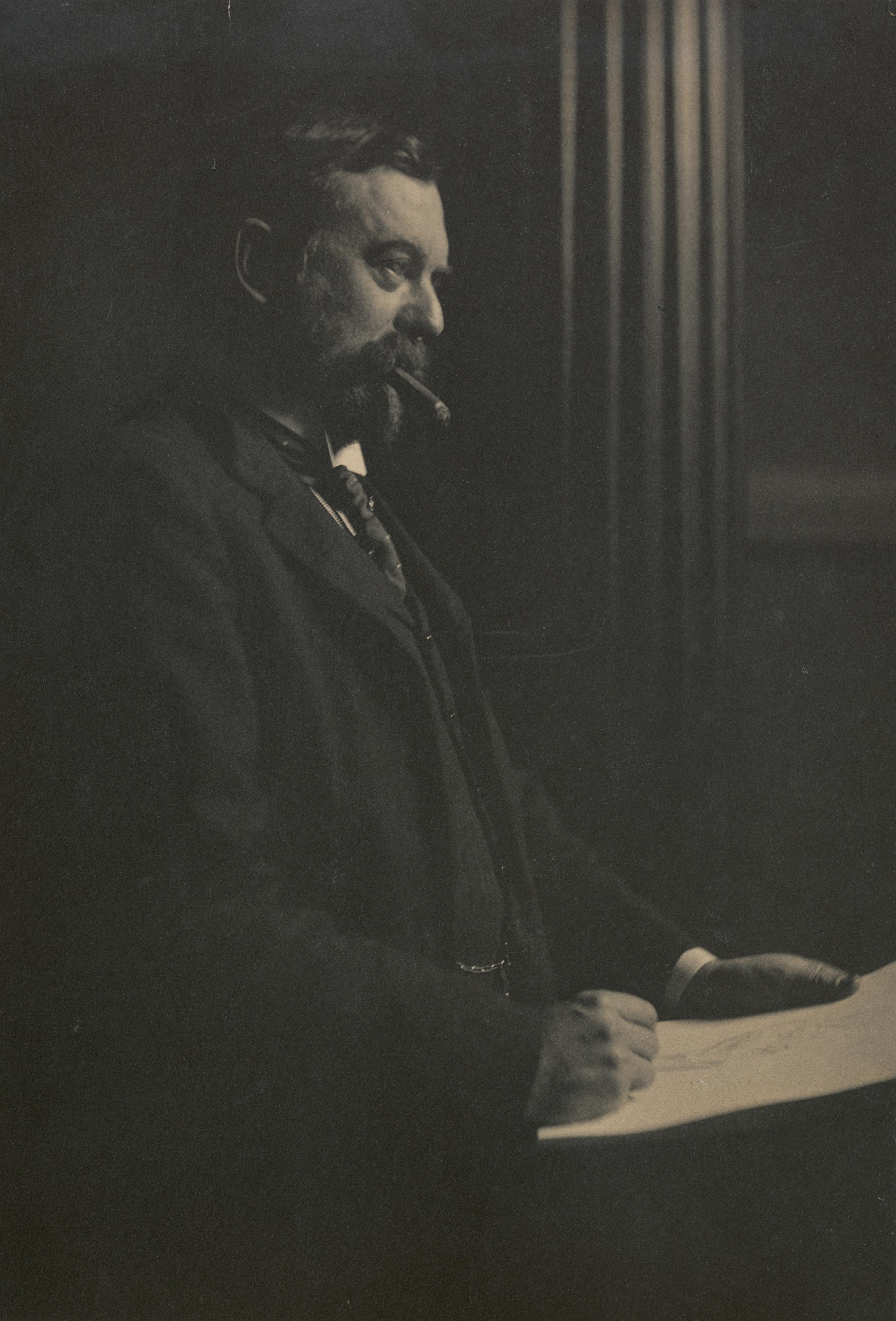

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.003948)

Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858–1935), John Singer Sargent Drawing Ethel Barrymore, 1903. Platinum print, 22.5 x 14.5 cm (8 7/8 x 5 11/16 in.)

Painting Isabella

Sargent arrived in Boston in November 1887 and worked on Isabella’s portrait for nearly two months in Gardner’s Beacon Street home. His opinionated sitter, who wears an evening gown designed by the Paris couturier Charles Frederick Worth, proved difficult, and progress was contentious. The result was a magnificent and provocative fusion of the pair’s mutual interests in iconic imagery and fashion—and a shared drive to challenge convention. Gardner and Sargent became lifelong friends in the process.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.008034)

John Thomson (British, 1837–1921), Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1888. Platinum print on paper with autograph in ink, 24.5 x 20 cm (9 5/8 x 7 7/8 in.)

Sargent fussed over an appropriate backdrop for Isabella’s painting, stating he wished he had brought a brocade from his studio. Gardner supposedly replied, “Never mind that, Sargent; I knew exactly what would be the proper background for my portrait when I decided to have you paint it.” She revealed a piece of fabric that was apparently just what Sargent had in mind. The story may be apocryphal, but it shows Gardner’s close collaboration with the artist. Typically, Sargent did not simply copy the pattern of this now faded fabric but elaborated, enlarged, and modified it to achieve a suitable artistic effect.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (T27w62)

Italian, Furnishing and Garment Fabric, 1475–1525. Silk: cut voided velvet, gilt yarn, 152.4 x 58.4 cm (60 x 23 in.)

Sargent’s portrait satisfied Gardner’s thirst for theatricality. Isabella faces us directly, as if about to speak. She embraced an iconography of power, a figure to be worshiped, adorned with jewels, and crowned with a halo-like pattern behind her head. The image seems to reference her deep spiritual interests. Gardner was Episcopalian but fascinated by the pageantry of Catholicism. Her pose and the framing of her head recall images of madonnas on display in Spanish churches, particularly in the south of the country. Sargent—who traveled in Spain extensively in 1879—gave Isabella a small sketch of a Spanish Madonna that he likely completed during his travels. One can see how Isabella is posed like the Virgin Mary with a frontal pose, clasped hands, and halos behind their heads.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P27w2). See it in the Long Gallery.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), A Spanish Madonna, about 1879. Oil on panel, 34 x 15 cm (13 3/8 x 5 7/8 in.)

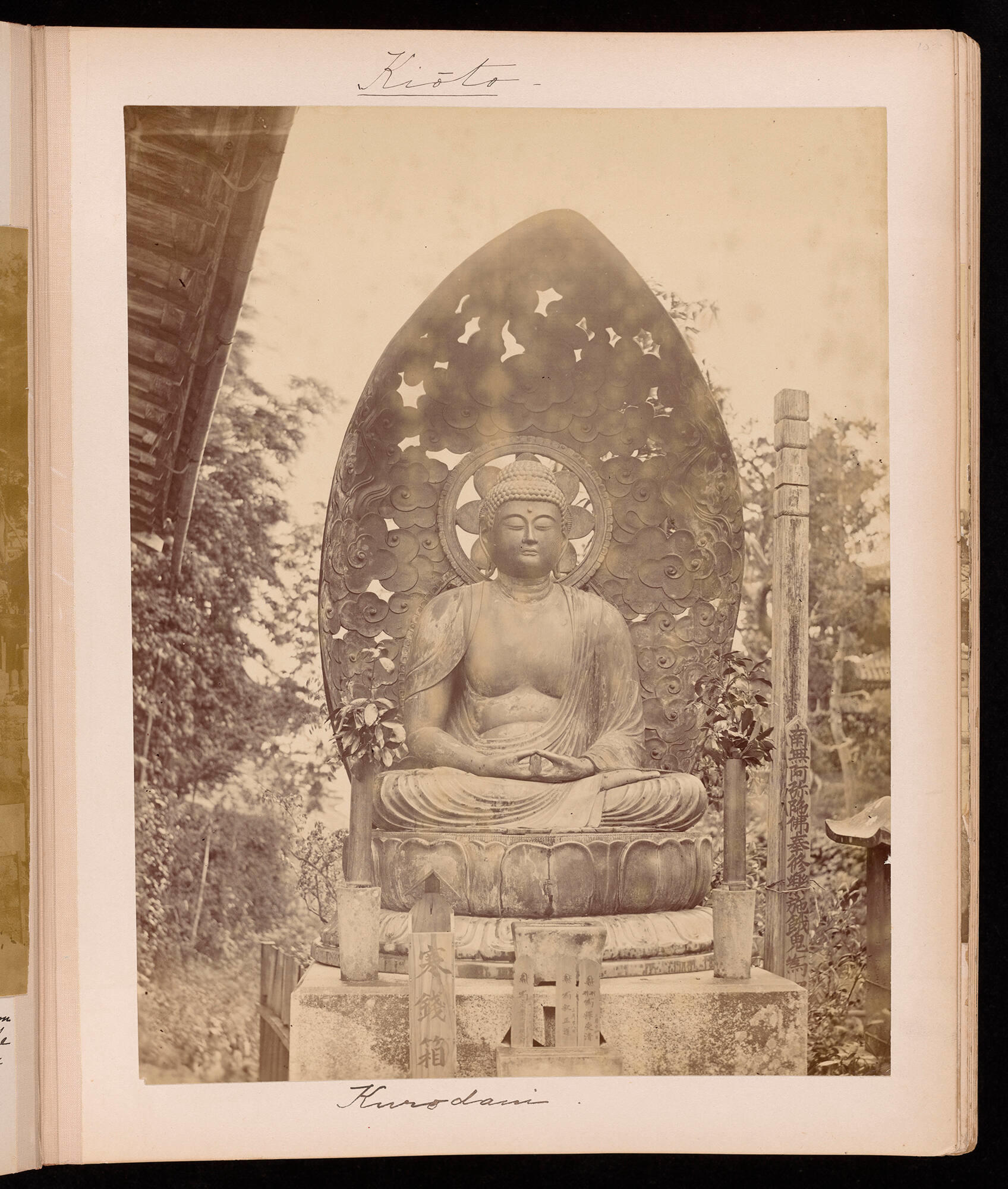

Sargent’s portrait may also reference another of her spiritual interests: Buddhism. From 1883 to 1884, Gardner and her husband traveled throughout Asia, where she often noted Buddhist practice and imagery in her travel albums. She collected several Buddhist sculptures, including the Buddha Calling Earth to Witness in the Yellow Room. The patterns behind her head both seem to echo a lotus motif and recall flaming halos similar to ones she would have seen behind statues of Bodhisattvas during her travels.

The Portrait’s Debut

Public reaction was decidedly sexist and predictably scandalized when the portrait debuted at the St. Botolph Club in 1888. The painting became a target, enabling local audiences to condemn her entitlement and her willful disregard of the conventions placed on upper-class women. Though her black evening dress was no more revealing than those of other portrait sitters, public comments about her being painted “all the way down to Crawford’s Notch” (a scenic sight in New Hampshire) alluded specifically to Isabella’s rumored affair with F. Marion Crawford, a novelist fourteen years her junior.

Upset by these comments, Jack Gardner asked his wife not to show the portrait again publicly. Until 1924, when Isabella died, it was visible by invitation only. However, visitors may have been able to peek through the gate that separated the then-private Gothic Room from the public museum spaces during Gardner’s lifetime.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner in the Gothic Room as seen through the Second Floor Stairhall gate

Gardner never lost her fascination for Madame X, the painting that first brought her to Sargent. She kept a postcard of the famed portrait of Virginie Avegno Gautreau (1859–1915) in the Sargent/Whistler Case in the Long Gallery, and she purchased one of Sargent’s related oil sketches, Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast. Gautreau appears in profile in the study, with her shoulders and chest visible through a transparent shawl.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P3w41).

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856 - 1925), Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast, 1882-1883. Oil on panel, 32 x 41 cm (12 5/8 x 16 1/8 in.)

Gardner hung this painting in the Blue Room, just across from a portrait of Henry James, who launched the exceptional and provocative collaboration between patron and artist by introducing Gardner and Sargent.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Who’s Laughing in the Gothic Room

Read More on the Blog

John Singer Sargent, Isabella Stewart Gardner, and Spain

Explore the Exhibition

Inventing Isabella