In 1888, Isabella Stewart Gardner and her husband, John Lowell Gardner Jr., traveled to Europe. The couple made plans to visit Spain for the first time, an encounter that forever impacted Isabella Gardner in its cultivation of her love for Spanish art and culture. In commemoration of this trip, Gardner compiled two travel albums (v.1.a.4.15 and v.1.a.4.16) that allowed both her and its future readers to retrace the steps of the journey. Her impressions of the country captured within these albums shaped the formation of her growing art collection. They also impacted the very walls of her museum with the construction in 1914 of the Spanish Cloister to house John Singer Sargent’s El Jaleo—the painterly embodiment of Sargent’s own trip to Spain—which Gardner had admired since first laying eyes on the picture shortly after it was completed.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

Gardner’s decision to travel to Spain stemmed from several weeks she spent in Sargent’s company as he painted her portrait in January 1888. Learn more about their shared interest in the blog post Isabella Stewart Gardner, John Singer Sargent, and Spain.

Both Gardner and Sargent had been swept into a much broader cultural fascination with Spain, and attendant ideas of “Spanishness” that developed during the mid- to late nineteenth century. The word “Spanishness” first became part of the English language during the 1830s, around the same time that the equivalent term began to appear in French and Spanish. It is still employed frequently without much clarification for what it means beyond an attempt to describe the shifting stereotypes concerning the qualities of being Spanish.¹

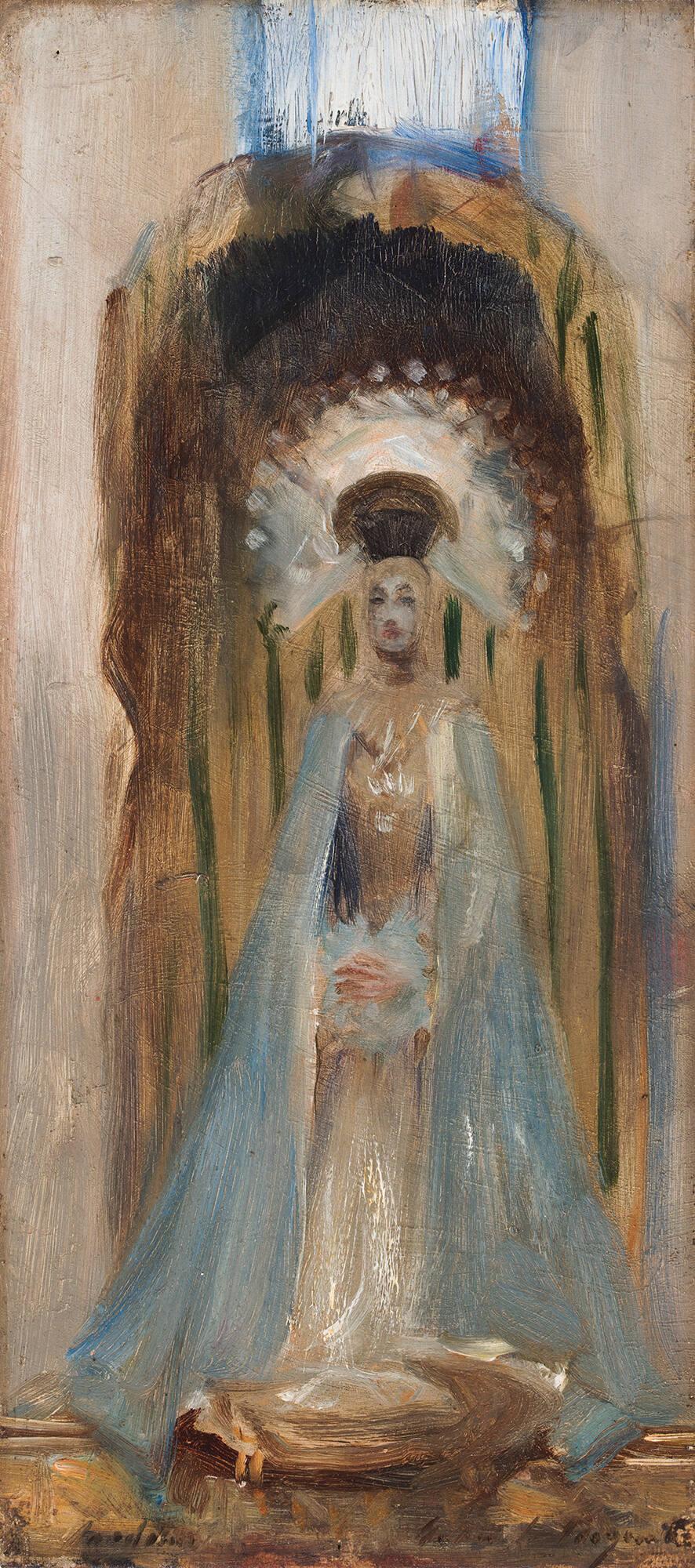

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P27w2). See it in the Long Gallery.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), A Spanish Madonna, about 1879. Oil on panel, 34 x 15 cm (13 3/8 x 5 7/8 in.)

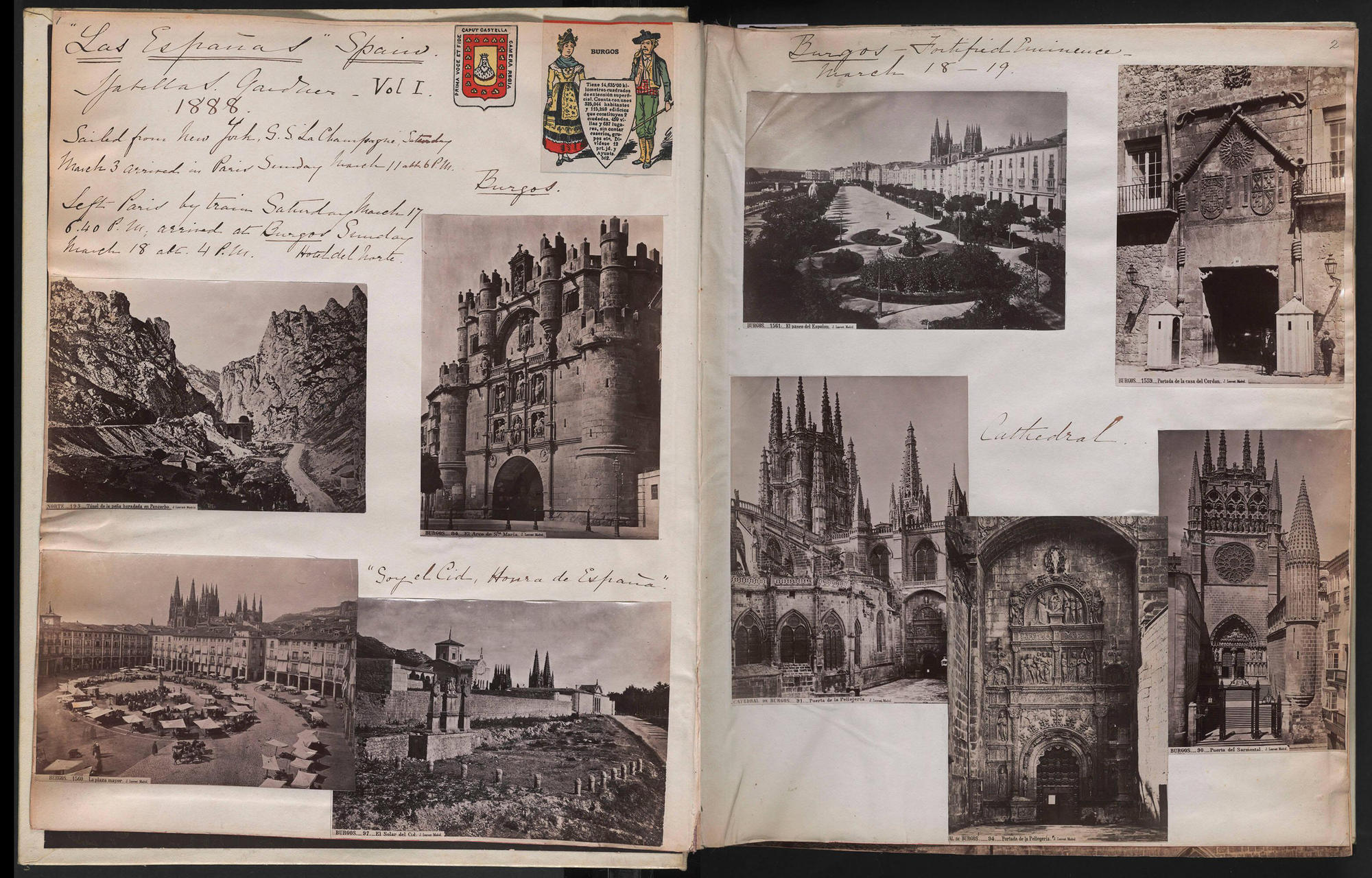

Arriving in Spain on 18 March 1888, the Gardners started their trip in Burgos and remained in the Iberian Peninsula for three months. They toured the full breadth of the country, traveling to Madrid, Seville, Cadiz, San Fernando, Gibraltar, Malaga, Granada, Cordoba, Toledo, Leon, Segovia, and Barcelona, an itinerary that is unique from that of other foreign travelers, who were primarily interested in seeing only Madrid and Andalusia. The Gardners consumed all aspects of the cultures of the Peninsula, from east to west, north to south, with particular focus on splendors of historic art and architecture, as if it were a place frozen within the past. Gardner’s albums are powerful recreations for her memories and future readers of her perceptions of what defined Spanishness.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (v.1.a.4.15). Isabella kept her travel albums in the Vatichino.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840–1924), Travel Album: Spain, Volume I, 1888. Parchment-covered album including collected photographs, found papers, and pen and ink annotations, pages 1–2

The first volume focuses primarily on her time in Madrid and over fifty pages are taken up with photographs—often trimmed to fit within her collages—of her favorite works from Madrid’s Museo Nacional del Prado and Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando by artists such as Velázquez, Murillo, Titian, and Goya. Gardner creates a textbook-like reference of historic monuments and celebrated artworks that presumably informed her own future purchases of Spanish art.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (v.1.a.4.15). Isabella kept her travel albums in the Vatichino.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840–1924), Travel Album: Spain, Volume I, 1888. Parchment-covered album including collected photographs and pen and ink annotations, pages 23–24

Gardner introduces the second volume of her albums with:

Spain says it all.

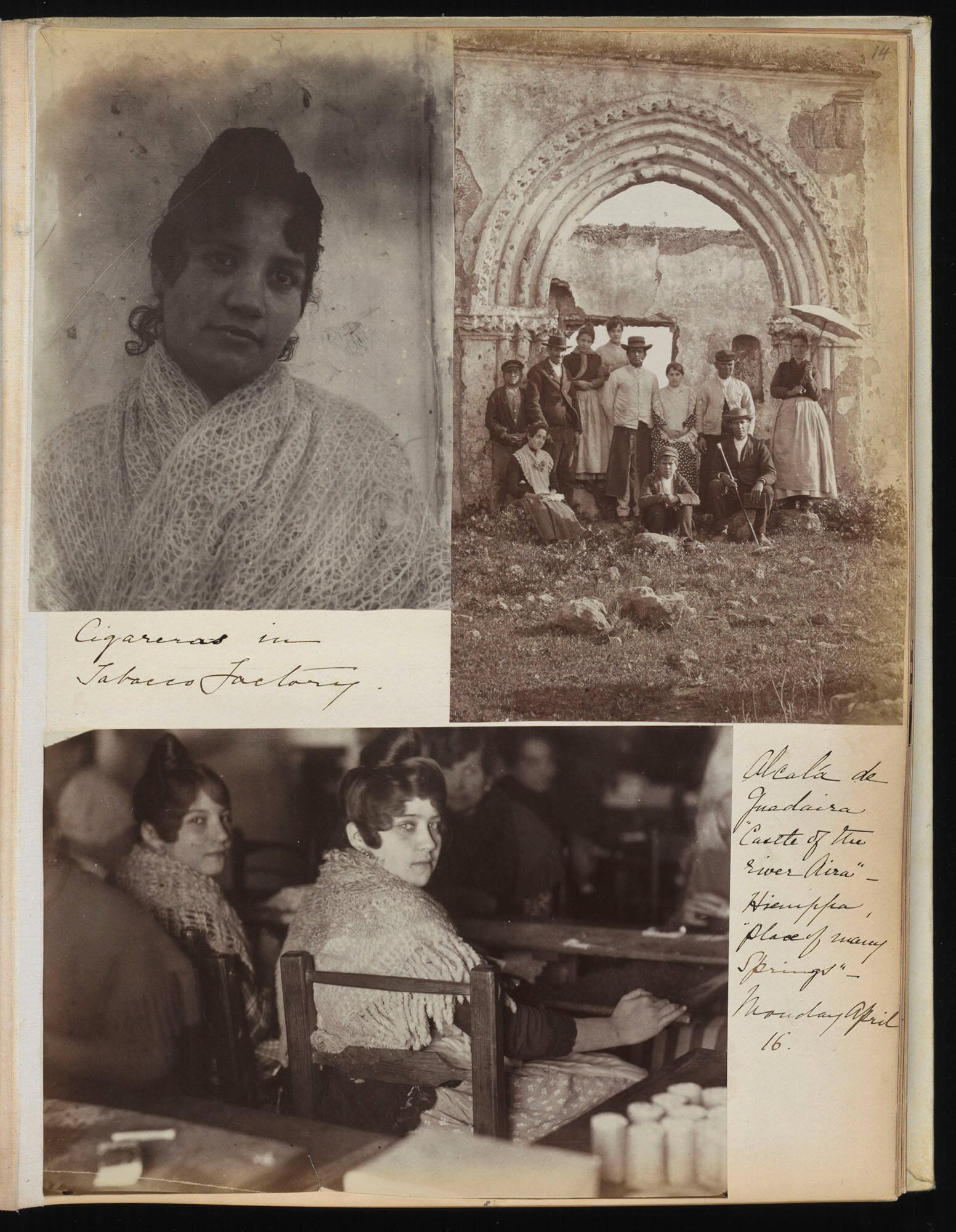

The subsequent pages mark a transition within Gardner’s trip as she begins to live in Spain’s present and not solely within its past. It is not until this volume that Gardner introduces photographs of Spaniards among those of Spanish art and architecture. Andalusia, especially Seville and Granada, was (and still is) seen as the epicenter of Spain’s multicultural and interracial past and present, given its deep history as a meeting point for European, North African, and Roma cultures. As Jack Gardner wrote to his nephew George of their travels: “The places are interesting but the Spanish ––! Oh!! In the South of Spain they are much more cleanly than in the north, supposed to be a relic of Moorish Civilization.²” The photographs of Spaniards that Gardner selected for this volume perform the stereotypes of Spanishness prevalent within her time, exposed through their dark skin and posed in typologies of traditional dress.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (v.1.a.4.16). Isabella kept her travel albums in the Vatichino.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840–1924), Travel Album: Spain and Portugal, Volume II, 1888. Parchment-covered album including collected photographs and pen and ink annotations, page 14

On 23 April, Gardner purchased her first European Old Master painting in Seville, the Workshop of Francisco de Zurbarán’s Virgin of Mercy. This acquisition also marked the beginning of Gardner’s collecting of Spanish paintings. Many of her contemporaries followed suit, for the first time beginning to see Spanish art on par with its European peers. Gardner continued to collect Spanish art for the rest of her life and ultimately acquired works by Velázquez, Bartolomé Bermejo, Pedro García de Benabarre (1455–1480), as well as a second Zurbarán. Her albums served as the ideal photographic resources needed to make informed decisions about her purchases.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P6n2). Photo: Sean Dungan

Workshop of Francisco de Zurbarán (Spanish, 1598–1664), The Virgin of Mercy, 1640, in the Spanish Chapel

Gardner was enthralled by Spain for the rest of her life and, through her albums, could return to her time in Spain and the diverse layers of Spanishness that she had come to emulate within her own museum.

You May Also Like

Read the Book

Fellow Wanderer: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Travel Albums

Read More on the Blog

Isabella and the Hispanic Society

Read More on the Blog

Spanish Music, South Korean Choreographers, and the Museum Archives

¹ Read more about the nineteenth century exoticizing of Spain in Madeleine Haddon’s essay “‘Spain Says It All’: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s 1888 Travel Albums of Spain” in Diana Seave Greenwald and Casey Riley, Fellow Wanderer: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Travel Albums, 2023.

² John L. Gardner Jr. to George Peabody Gardner, 24 May 1888, Gardner family papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.