Isabella Stewart Gardner loved Spanish art and music, a taste fostered by her friends, including John Singer Sargent. The two adored flamenco music, traded records, and wrote their judgments on the labels, just as today you might “like” a song on Spotify or share playlists with friends.

Juanito Pardo (Spanish, 1884–1944) and Victor Talking Machine Company (American, active 1901–1929, publisher), Flamenco Record: "Zaragozanas Puras No. 1," "Zaragozanas Netas," early 20th century

In part, her personal interest reflects a moment in American history when “Hispanism”—a fascination with the Spanish speaking world, its cultures, and peoples—was all the rage. So powerful was the movement that even the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898 did little to diminish its popularity. But for Gardner, a love of all things Spanish was more than a passing fad. She travelled to Spain and its former colonies and filled her museum with Spanish and Mexican artworks, as well as the paintings of contemporary artists inspired by their own visits. Her collection even impressed the most dedicated American Hispano-phile: Archer M. Huntington.

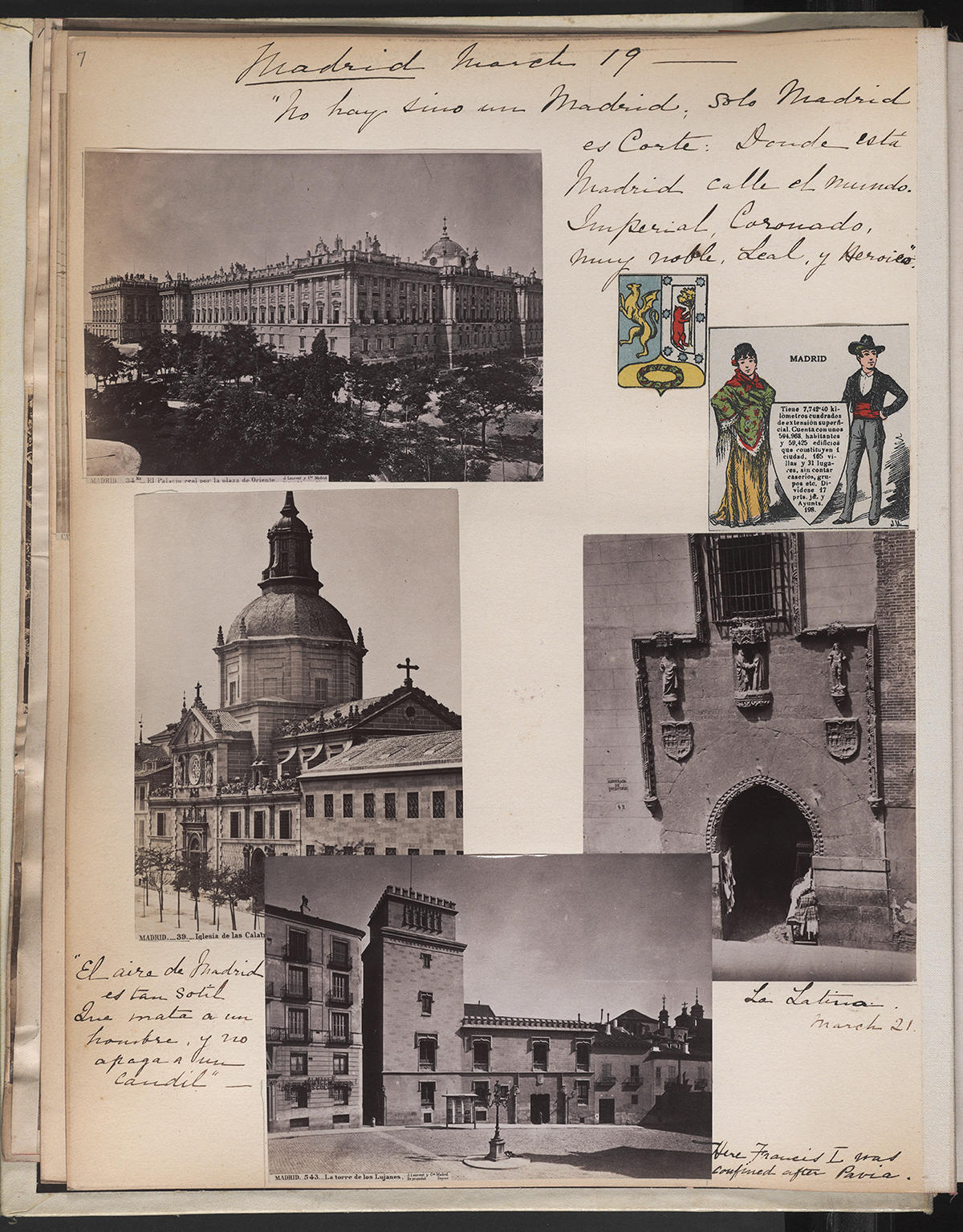

Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924), Travel Album: Spain, Volume I, page 6, 1888

In early 1911, Isabella’s close friend A. Piatt Andrew—then Secretary of the Treasury—wrote to her of a weekend planned for Archer Huntington and his wife, Helen, at his summer home Red Roof, in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Huntington, the only son of a railroad and shipping magnate, had been fascinated with Spain since childhood. He lived with an aunt on her Texas ranch and at age nineteen travelled with his parents in Mexico. By the time he visited Spain for the first time, Huntington spoke the language, was studying Arabic to better acquaint himself with this aspect of the country’s history, and had already decided to create a “Spanish Museum.”

Archer Huntington in Spain, following the route of El Cid from Burgos to Valencia, 1892

Only one year after Gardner’s Fenway Court opened to the public in Boston, Huntington founded the Hispanic Society of America in New York City, a museum dedicated to the art and culture of the Spanish-speaking world and featuring his own masterpieces by Velázquez, Murillo, and Goya.

Main Courtyard of the Hispanic Society of America Museum and Library, 1908

Andrew explained to Gardner that he had only secured the Huntingtons' attendance in Gloucester by promising them a visit to her museum in Boston: “I have boldly held out Fenway Court as a lure, and they have consented to come.” Sadly no record of their impressions survives. We can only imagine the Huntingtons’ admiration for Gardner’s collection. She owned Saint Engracia, a rare work by the Spanish Renaissance painter Bartolomé Bermejo, one of the few known portraits by Zurbarán, a portrait of Philip IV by Velázquez, and even a recently purchased Manet painting inspired by the latter and executed shortly after the French Post-Impressionist master’s 1865 visit to Madrid, in addition to the the many other books and objects attesting to Isabella’s love of Spanish culture.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P21s28). See it in the Dutch Room.

Francisco de Zurbarán (Spanish, 1598–1664), A Doctor of Law, about 1635. Oil on canvas, 195.5 x 104.5 cm (76 15/16 x 41 1/8 in.). Note the red chair that the figure rests his hand upon.

By this time, Gardner had also made a big decision—choosing to enshrine Spain at the heart of her museum. She undoubtedly shared these plans with the Huntingtons, even though they were realized several years later. In 1914, Gardner replaced the Music Room with several galleries including the Spanish Cloister. Inspired by Andalusia, the space features a Moorish arch and mosque tiles, architectural fragments from Spanish Romanesque and medieval French buildings, and a wall lined with tiles from a Mexican church—all anchored by El Jaleo, Sargent’s monumental genre scene of a Spanish gypsy dance.

The Spanish Cloister, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2014

Photo: Sean Dungan

At the opposite end of the same space, she built the Spanish Chapel and hung a painting by the workshop of Zurbarán, the Virgin of Mercy, over its altar and placed a tomb figure of a Spanish knight on the floor.

The Spanish Chapel, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2010

Photo: Sean Dungan

Clearly impressed by what he saw on the 1911 excursion, Huntington wrote to Gardner shortly after returning to New York. He invited her to join the board of the Hispanic Society “in recognition of the honor due to those who have rendered the highest service to art or literature in some measure related to the field of our work.” Huntington positively brimmed with admiration for her achievements.

It would be childish to praise alone what you have built when it is within my power to frankly admire the author of the greatest work done by an American woman. Surely you will forgive a badly turned phrase—which comes from the heart.

Transforming words into action, he followed up with an invitation for Gardner to join the Advisory Board of the Hispanic Society. She became both a member of the society and its first female board member. Proud of her involvement, she displayed Huntington’s letters, her membership certificate and medal in the Presidents and Statesmen Case in the museum’s Long Gallery.

Spanish culture stayed close to Gardner’s heart. She remained friendly with Huntington for the rest of her life and continued her flamenco record exchange with John Singer Sargent during his extended stays in Boston of the late teens and early twenties. Upon her death in 1924, Gardner’s body was displayed in the Spanish Chapel and a requiem Mass celebrated her memory.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Read more on the blog

A Tiny Sombrero

Learn about the Cases

Fifteen Hidden Cases

Read more on the blog

Spanish Music, South Korean Choreographers, and the Museum Archives