… A Museum for the education and enjoyment of the public forever …

This statement of purpose quotes directly from the Will and Codicil of Isabella Stewart Gardner, probated on July 23, 1924 in the Probate Court of Suffolk County. Through this document, Isabella declared her intent for the institution she had built and filled with masterpieces spanning the globe and the centuries. She considered the collecting of objects and the establishment of the Museum to be an act of civic leadership, improving the lives of Boston’s residents through access to beauty and the inspiration of direct encounters with art. She also had very particular views on the aesthetic experience, installing her galleries in a way that promotes intimacy, emotional response, and individual interpretation over didactic approaches governed by medium, geography, or period style.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

Isabella’s Venetian-inspired Courtyard

It is the privilege and responsibility of every Gardner Museum director to interpret Isabella’s legacy for a new era and new generations of Bostonians, to ensure its relevance and sustainability in a changing society. This can be uniquely challenging in a museum that cannot collect and cannot rearrange the works of art within its historic galleries. So when I came to the Gardner, I asked myself, “Who was the public to whom Isabella bequeathed her Museum? Was Boston around 1900 anything like the Boston we know today? What civic issues did Isabella care about and how might that inform the Museum’s future?”

Historic New England (PC001.02.01.USMA.0340.6760.003)

William T. Clark (active Boston, 1920s-1930s), Quincy Market and South Market Street, Boston, about 1920. Photograph

Upon my appointment in 2016, as I met people throughout the city and began to know the Gardner’s staff, I queried them on their perceptions of the Museum’s founder. I often heard the terms “bold,” “creative,” and “scandalous.” I observed that people credited Isabella with a passion for collecting, astute aesthetic judgment, adventurous patronage of artists, unconventional behavior, and indifference to the opinions of others—if not actual cultivation of a negative public image. While other scholars have explored eccentricity as a strategy adopted by upper-class women like Isabella to gain autonomy and agency within the strictures of gendered power structures, this analysis was seldom applied to Isabella in the public imagination. The public instead would sometimes see the creation of her Museum as an egocentric undertaking rather than an act of civic good. Rather than focus on the serious purpose of Isabella’s will, they privileged the somewhat frothy spirit of the phrase “C’est mon Plaisir”—translated to “It’s my pleasure”—that appears below the corporate seal and crest on the Museum’s façade. And in this view, Isabella herself had little to teach us beyond female independence and a fearless pursuit of one’s creative passions—both noble characteristics, but hardly a blueprint for an institution’s future.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.007386)

Sarah Wyman Whitman (American, 1842–1904), Sketch for the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s Seal, 1900. Ink on paper.

However, when I began investigating the Boston Isabella encountered, I realized how closely it aligned with the city we know today. In 1900, 35% of the population here was foreign born (it was roughly 25% when I came in 2016). Although the primary countries of origin differed from current immigration trends, the challenges faced were similar, including overburdened infrastructure, needs for housing, education, and job training, particularly among women whose economic circumstances required them to work.

Historic New England, Mary H. Northend photographic collection, 1904-1926 (PC034.TMP.216)

Woman painting a vase at the Paul Revere Pottery in Boston’s North End, about 1914. The Pottery trained and employed immigrant women.

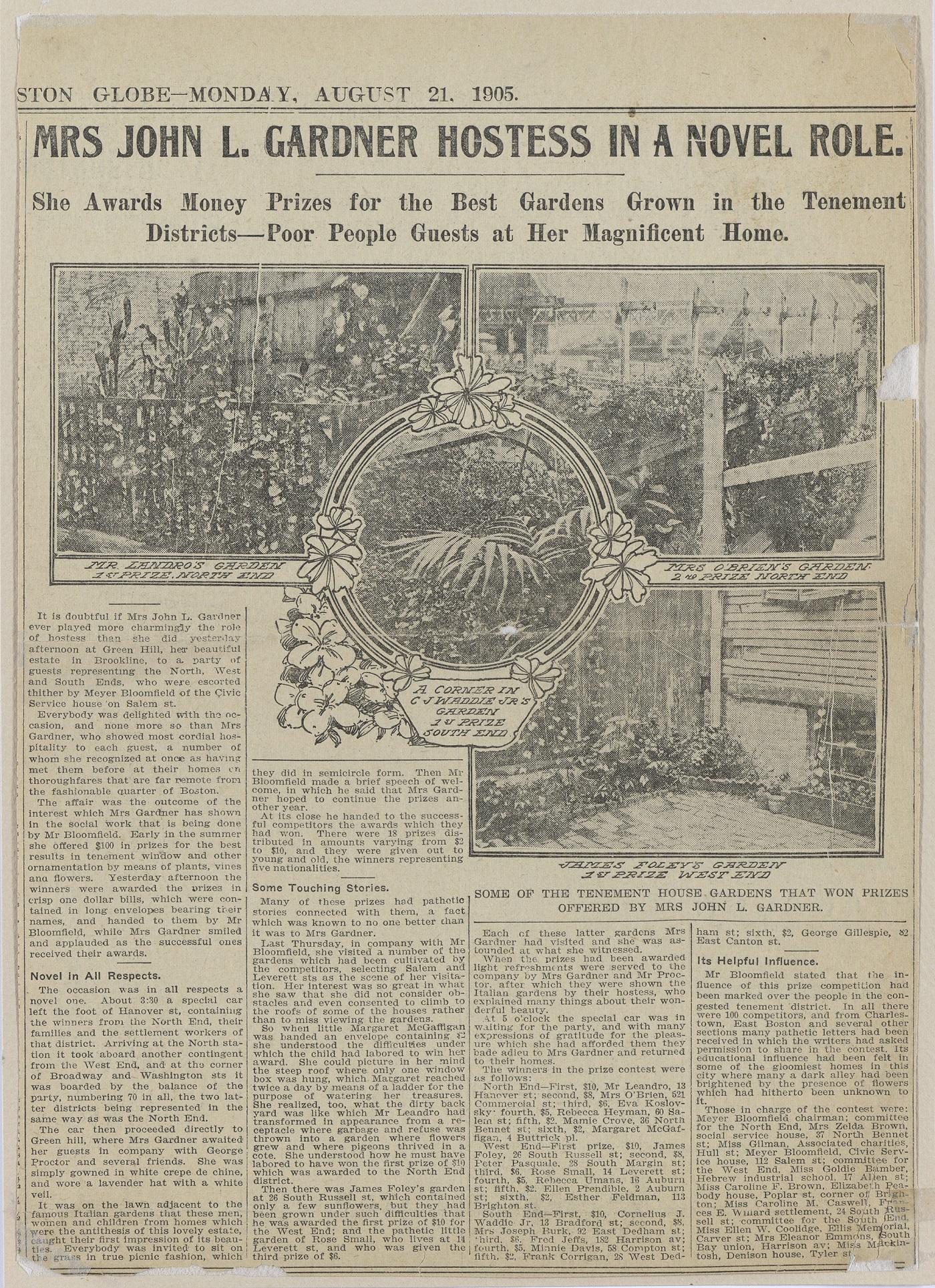

Isabella’s charitable activities beyond her creation of the Museum included both the gift of her time and energy, as well as cash contributions. There was often an intersection between her artistic patronage and personal passions. For example, with the Romanian Jewish community activist Meyer Bloomfield, she established and funded a tenement garden contest, hosting the winners at her Brookline estate, Green Hill, and connecting her own love of horticulture with efforts to beautify living conditions for the city’s poor. She actively raised funds for disaster relief, people with disabilities, and child welfare agencies. She supported a pro-immigration candidate, A. Piatt Andrew, over her own nephew in the congressional race of 1913, causing a family rift. She often used the Museum as a platform for both avant-garde artistry and fundraising—Ruth St. Denis performed her controversial “cobra” dance in 1906 to garner support for the Holy Ghost Hospital for the Incurables. And as much as Isabella may have been a product of some of her era’s prejudices, she often embraced those whom high society would otherwise marginalize for their racial or sexual identities.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.100018)

Boston Globe (established Boston, 1872), “Mrs. John L. Gardner: Hostess in a Novel Role,” 21 August 1905. Newspaper clipping

The power of art resides not only in beauty, but in its ability to engage complexity, multiple perspectives, and new possibilities. Isabella was as ambiguous an individual as we might imagine, but her legacy manifests an ambition to wed the Museum she created with civic purpose—to embrace communities too long disadvantaged by exclusion, to harness artistic risk-taking to social causes, to be engaged with the needs of the city and its residents in an ever-changing society. That is a legacy one can build upon, and that is what informs the Museum’s strategic direction today—to connect the historic art in our collection, contemporary artistic practice, and the issues of our time in a meaningful exchange that in turn builds relationships with and among the public to whom Isabella bequeathed her wondrous institution. And we can continue to admire Isabella for the bold, independent, controversial woman she was and still is in the hearts of so many.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Sound Check: First Concert Hall Audience

Read more on the blog

Open House: How Isabella’s Home Exhibition Funding the Trailblazing Coting School

Read More on the Blog

Back to School with Isabella