It is a common misconception that the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum was Isabella’s house. Fenway Court, as it was called during Isabella’s lifetime, was a purpose-built museum for the “education and enjoyment of the public forever.” It was also the first museum to be built by a woman. However, Isabella did create private living quarters on the fourth floor of the Museum, where she lived from 1901 until her death in 1924.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Metropolitan News Company (active 1905–1916, publisher), Mrs. Jack Gardner’s Palace, Boston, Mass, 1906. Color lithograph; ink on paper

Director's Use

After her death, Isabella dictated that the Director of the Museum could live on the fourth floor, rent free, for the term of their stewardship. The first three directors, Morris Carter (1924–1955), George Stout (1955–1970), and Rollin Hadley (1970–1988) lived on the fourth floor with their families. During their tenures, several spaces were renovated to update them for modern living.

Isabella left the contents of her fourth floor apartment to her niece, Olga Gardner Monks. Olga selected some personal effects and furnishings and donated what remained back to the Museum for the use of future directors.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.008124)

Unidentified photographer, Boston, Olga Eliza Gardner Monks and her Sons, 1901. Platinum print

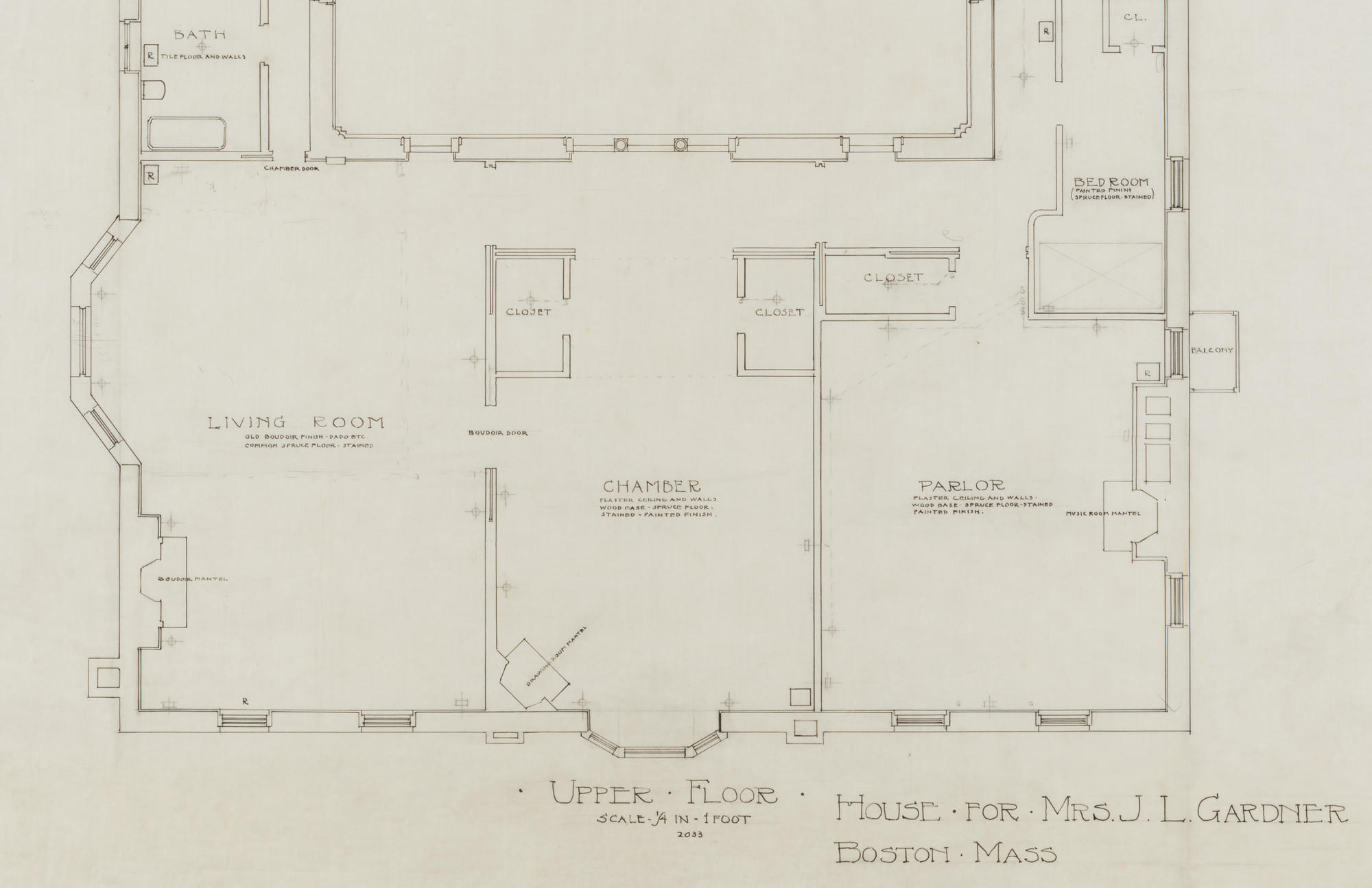

Today, the fourth floor is staff administrative offices, but it is fun to imagine what the space was like during Isabella’s lifetime. As someone who both carefully crafted her public image and protected her privacy, Gardner did not photograph her living quarters in the same way she documented the galleries in the Museum. But we do have a few clues that tell us about the rooms including firsthand accounts, floorplans, and inventories.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Willard T. Sears (American, 1837–1920) and Edward Nichols (American, 1864–1933), Plan of the Fourth Floor of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (detail), 1900–1914

Visiting Isabella on the Fourth Floor

Although Isabella generally entertained in the galleries of the Museum, she did have guests to her apartment including author Henry James, artist John Singer Sargent, actress Ethel Barrymore, women’s right advocate Julia Ward Howe, art historians and consultants Bernard and Mary Berenson, and opera singer Nellie Melba.

The large rooms were comparatively low-studded, handsomely and comfortably furnished, homelike with books and photographs and personal belongings, bright with lovely flowers—the kind of rooms any one of us would like to live in, with nothing of Cleopatra’s barge or of Isabella d’Este’s palace about them. Mrs. Gardner was often compared to one or the other of these sumptuous ladies, but her private establishment was simple and unpalatial, no liveried servants, no ostentation of style. She lived economically, preferring to spend her wealth in buying masterpieces.

When friends came to visit her apartment they entered through the entrance on Worthington Street (now Palace Road) into a Lobby which was refurbished in 2017. It contains East Asian lacquer and a sideboard with a bowl for visiting cards.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Worthington Street Lobby, 2017

After arriving, visitors would take the elevator to the fourth floor which, during Isabella’s lifetime, was an open cage—it was enclosed in the 1950s. The open lift allowed visitors to see the Chinese and Japanese works of art in the elevator passages as they approached the apartment.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Second Floor Passage, 2024, showing two Japanese screens, Spring and Autumn

Morris Carter, Isabella’s biographer and first director of the Museum, wrote that she was trying to recreate “as nearly as possible” 152 Beacon Street—her beloved home with her husband Jack for over 35 years in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood. Isabella worked with Boston photographer Thomas Marr to document the brownstone, and those pictures give us an idea of what her apartment at the Museum may have looked like.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Thomas E. Marr (Canadian-American, 1849–1910), Isabella and Jack Gardner’s Back Bay home, 152 Beacon Street, 1900

Isabella salvaged architectural elements from Beacon Street and installed them in her fourth floor apartment. The first room that you encounter when you arrive on the fourth floor via the elevator is the Dining Room. The fireplace with 16th century Spanish tiles, Tiffany & Co. andirons, a ceiling of painted Japanese paper, and the 19th-century French Renaissance-style table are all from Beacon Street.

The silver tea paper on the walls likely dates to Isabella’s time. Made from tea box liners, it has a linseed oil finish over tin-leaf.

Domestic Workers

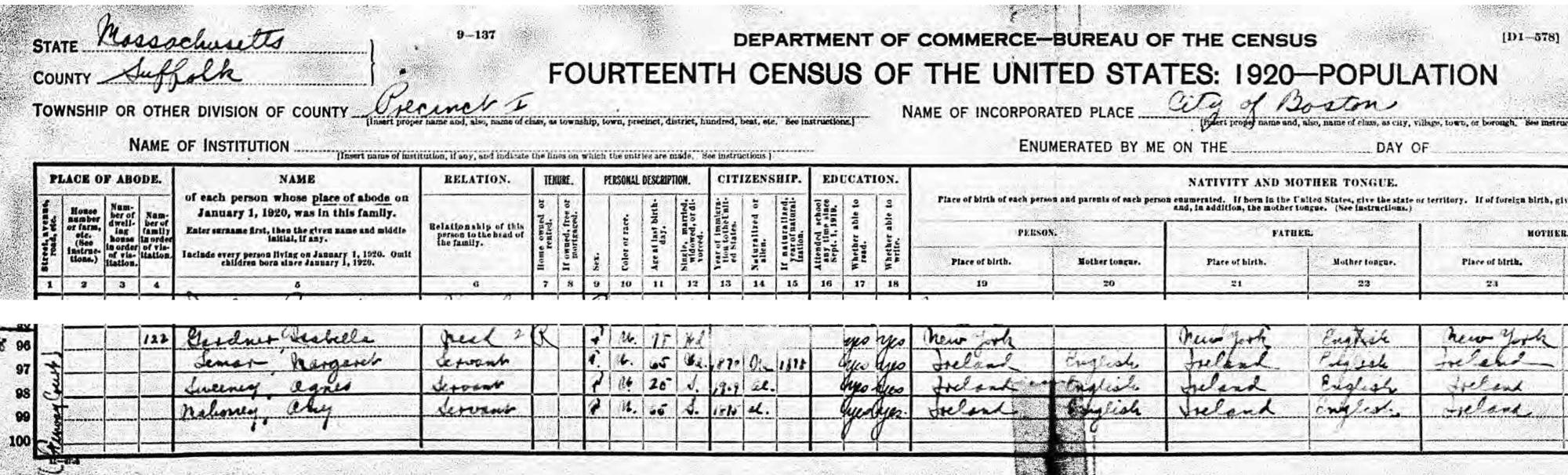

Isabella wasn’t the only person living on the fourth floor. As a wealthy woman, she employed household staff, including a housekeeper, maid, and cook. Unfortunately, many of their names and stories are lost to history. One resource to identify some of the people who lived with Isabella is the 1920 Federal census which lists three women who had immigrated from Ireland.

National Archives

Fourteenth Census of the United States, Massachusetts, City of Boston, 1920, showing the four women living at Fenway Court

Margaret Lamar was a 65 year old woman, born in Ireland, who moved to the United States in 1870 and became a naturalized citizen in 1898. Her occupation is listed as housekeeper. Margaret began working for the Gardners early in their marriage, shortly after she arrived in this country. She probably lived with them on Beacon Street and then moved to the Museum with Isabella. Margaret outlived Isabella who stipulated that she be allowed to stay in her living quarters after Isabella’s death. Margaret died in 1928, and she is buried in Saint Joseph’s Cemetery in West Roxbury.

Agnes Sweeny, the chambermaid, was a 25 year old woman, born in Ireland who immigrated in 1909. We don’t know much about Agnes, but she was at the Museum working for Isabella after her first stroke in 1919. She described John Singer Sargent’s watercolor of Mrs. Gardner (now in the Macknight Room) as “a fleecy cloud from heaven.”

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P11e13). See it in the Macknight Room.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), Mrs. Gardner in White, 1922. Watercolor on paper, 43 x 32 cm (16 15/16 x 12 5/8 in.)

Amy Mahoney, a 65 year old woman, born in Ireland, arrived in the U.S. in 1875. She was the cook. (We are always looking for more information about people who have worked at the Museum over the years. Please email archives@isgm.org if you have any stories, documents, or other things to share!)

Isabella, her domestic employees, and her pets (including dogs and birds) lived comfortably in the fourth floor rooms. Piano music—played by her and her guests, sometimes rang out. There were flowers grown in the conservatory and lots of books to read.

Isabella embraced the simple pleasures of life on the fourth floor, while visitors enjoyed the art-filled galleries she created on the floors below.

You May Also Like

Read more on the blog

From Omnibuses to Streetcars: Isabella and the T

Read More on the Blog

Visiting Fenway Court in the Days of Isabella

Read More on the Blog

Bolgi: The First Caretaker and Protector of the Museum