Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s The Magic Flute (1791) held a special place in Isabella Stewart Gardner and talented author and illustrator Maurice Sendak’s hearts, and has a long history in the city of Boston. The overture to the opera opened the dedicatory concert for the Boston Music Hall in 1852. The city saw its first full staging of the opera in 1860—the same year Isabella married Jack and moved to New England. That production came from New York City after a run at the Academy of Music. In fact, the opera was staged just a few blocks from Isabella’s childhood home. Gardner and The Magic Flute arrived in Boston at the same moment.

Mozart: The Magic Flute - Overture (Benjamin Zander - Boston Philharmonic Orchestra)

7 minutes

Written shortly before the Austrian composer’s death at the age of 35, the opera (technically a Singspiel) follows the quest of Prince Tamino and his sidekick Papageno. As they seek to rescue Pamina, the beautiful daughter of the Queen of the Night, who has been kidnapped by the mystical high priest Sarastro. With their magic flute and bells, Tamino and Papageno ultimately save Pamina, and their ordeals lead them to develop a deeper understanding of true love and happiness.

The characters traverse a series of fantastical landscapes and settings on their journey. This connection between The Magic Flute—also often referred to by its German name Die Zauberflöte—and magical worlds appealed to both Sendak and Gardner. Isabella chose the overture to the opera as one of the pieces to be played on the opening night of her museum in January 1903. For Sendak, The Magic Flute was an overture to his career as an opera designer: it was one of the first productions he designed, debuting at the Houston Opera in 1980.

Maurice Sendak, Design for Temple of the Sun backdrop, finale II, 1979–80, Watercolor and graphite pencil on paper on board

© Maurice Sendak Foundation, The Morgan Library & Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013, 2013.104:124. Photography by Graham S. Haber

Maurice Sendak’s Affinity for the Magic Flute

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), the famed author and illustrator of Where the Wild Things Are (1963), shared this love for the opera with the museum’s founder, Isabella Stewart Gardner. Beyond both being opera fans in general, both Sendak and Gardner particularly loved one work: The Magic Flute.

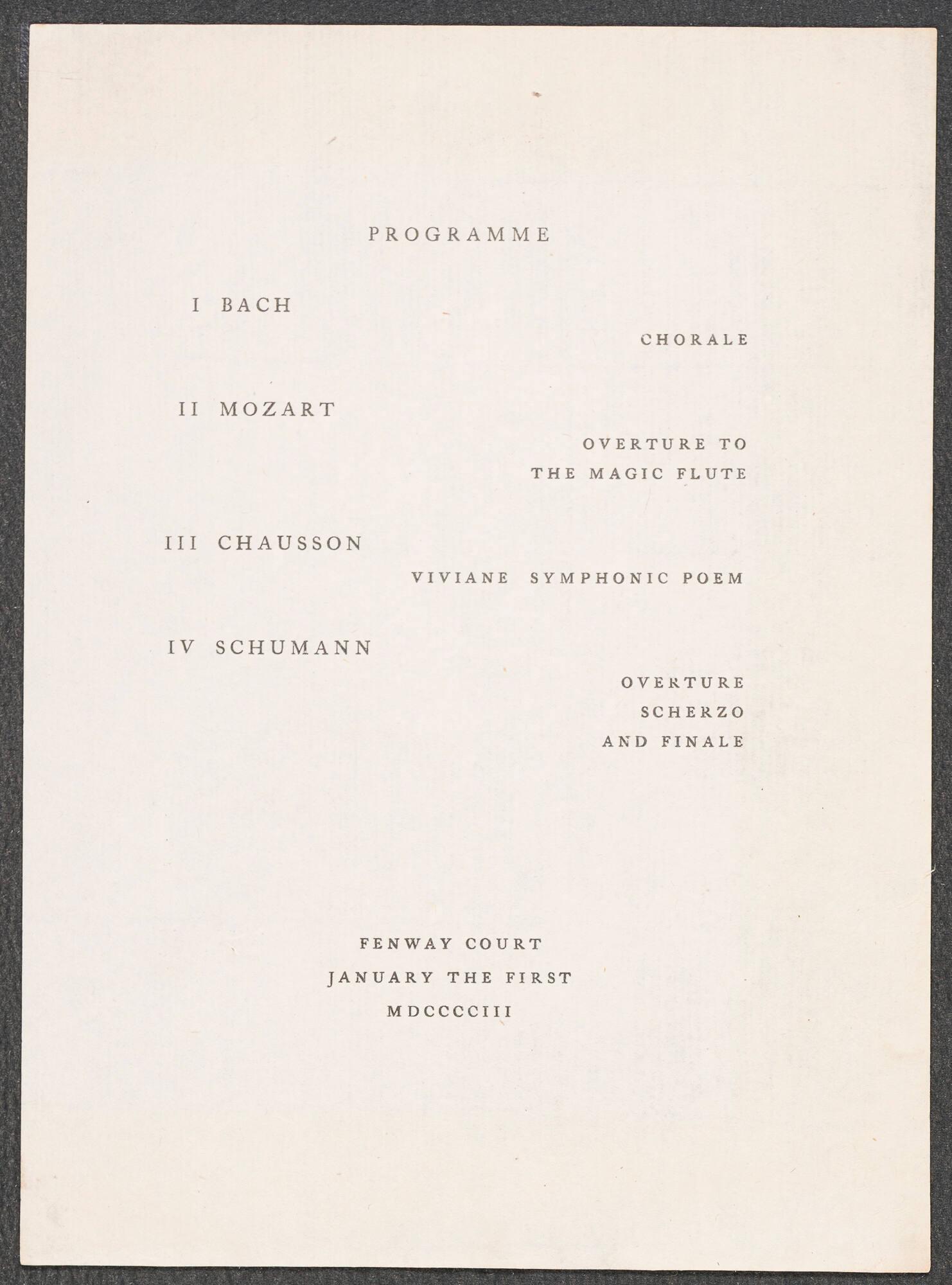

American, Boston, Concert Program for the Opening of Fenway Court, 1 January 1903. Ink on paper , 20.7 x 15.2 cm (8 1/8 x 6 in)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (ARC.007767). Isabella displayed this program in the Musicians Case in the Yellow Room.

After working in children’s literature for more than two decades, Sendak had a second career as a stage designer for opera and ballet. His designs for stage sets and costumes are the subject of a special exhibition at the Gardner Museum, June 16–September 11, 2022.

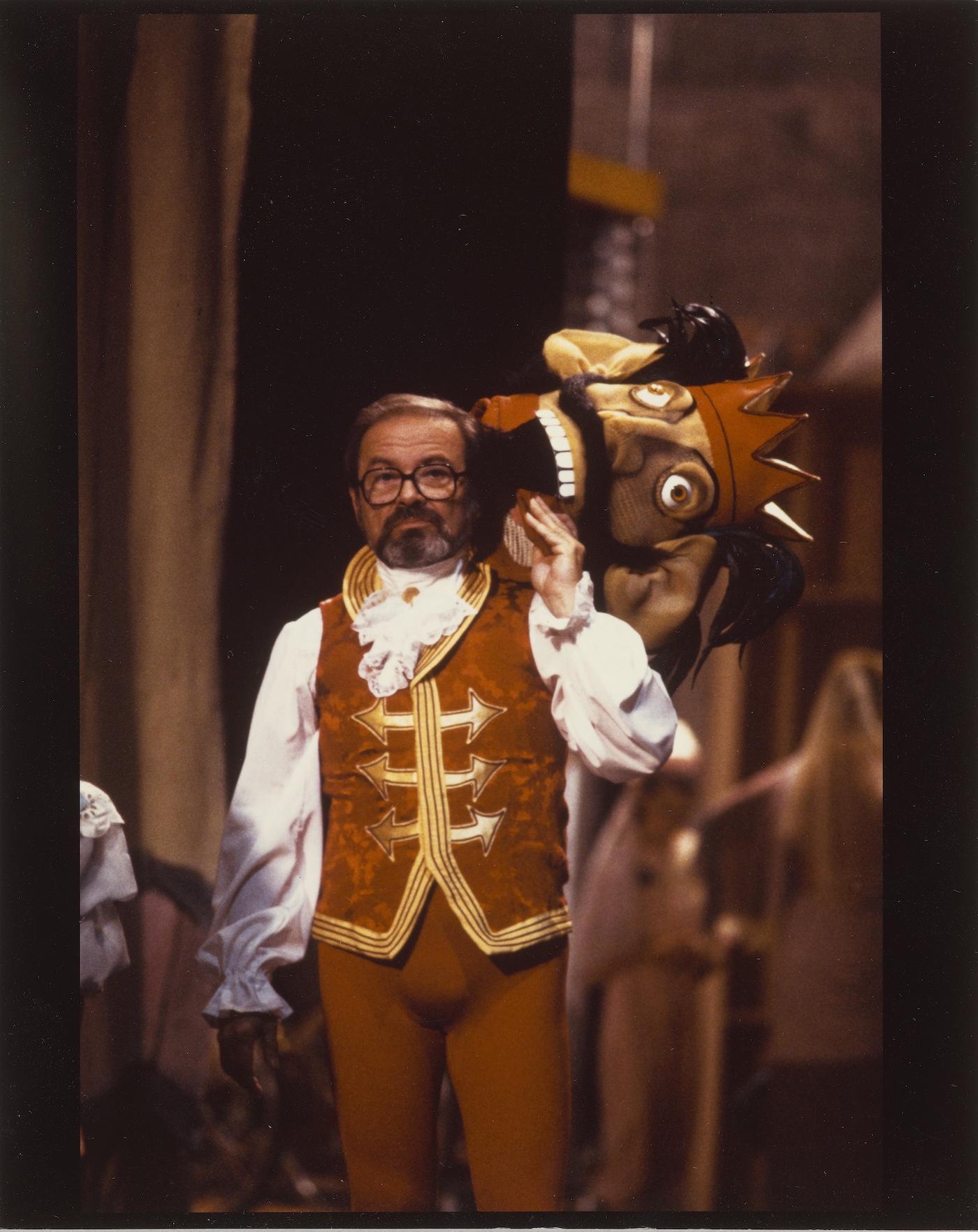

Maurice Sendak wearing the Nutcracker costume on the set of Nutcracker, The Motion Picture, 1986.

© Maurice Sendak Foundation, The Morgan Library & Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013, 2013.107:345.

When opera director Frank Corsaro (1924–2017) invited Sendak to create the stage design for a new Magic Flute production in 1978, he observed that Sendak’s picture books uniquely balanced darkness with levity. This delicate equilibrium translated beautifully to Sendak’s designs for The Magic Flute, an opera that similarly blends drama and humor. Sendak made many preparatory sketches—a range of which are on view in the exhibition—as he worked through the stage and costume designs for the production.

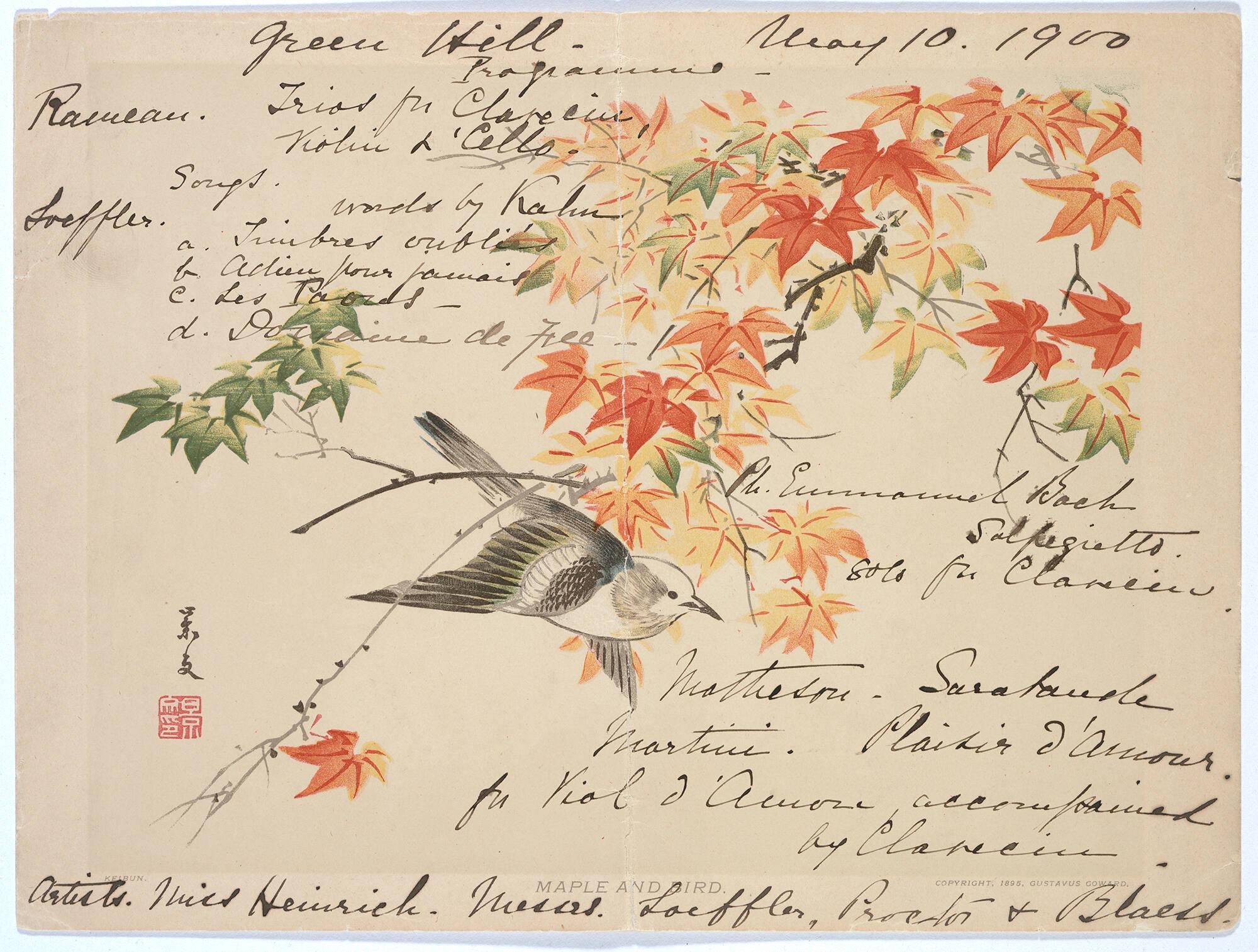

The performance at the Museum's opening was not the first time Isabella hosted a concert. At her homes on Beacon Street and in Brookline, she organized many concerts—often employing musicians from the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO). The Museum’s Archives hold copies of the programs for these performances, some of which were written on Japanese prints.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840–1924), Concert Programme, Green Hill, 10 May 1900, Ink on Japanese woodblock print

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (U33w39). Isabella kept this concert program in the Vatichino, her personal treasure trove.

Isabella & Wilhelm Gericke

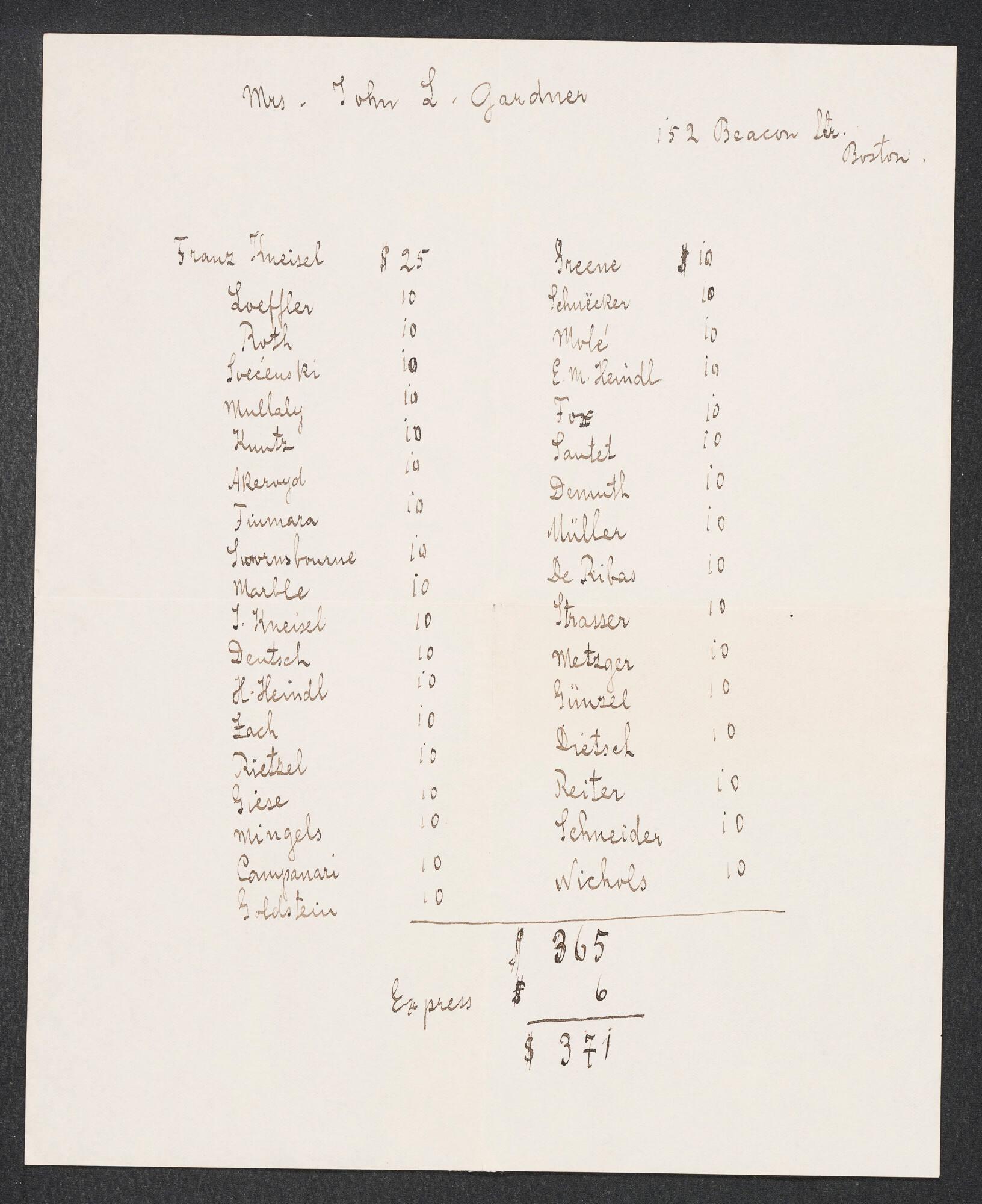

Gardner hired Wilhelm Gericke, a famed conductor of the BSO, to lead some of these concerts—an invoice he sent, apparently for a performance at Gardner’s Back Bay home, remains in the Museum’s Archives.

Wilhelm Gericke (Austrian, 1845–1925), Invoice for a Performance by Members of the Symphony Orchestra to Isabella Stewart Gardner, late 19th century–early 20th century. Ink on paper

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (ARC.001667). Isabella’s displayed invoice in the Musicians Case in the Yellow Room.

Therefore, it is unsurprising that she trusted him to serve as conductor for the Museum's opening night. Just days after the event, the Austrian conductor wrote to Isabella—in his somewhat broken English—about how he was moved by the experience of performing in such a magnificent setting.

Dear Mrs. Gardner,

I just came home from the town, still having all this deep and great impressions which I got in your palace; I cannot undertake anything before having expressed my warmest thanks for the great kindness and courtesy with which you had showed us all the beauties and wonders in your “Feenpallast" [Fairy Palace in German]. I cannot find words to express my admiration for all…I had seen, so also, I am quite unable to express my greatest respect and highest admiration for your knowledge about history, Art and architecture…

I am so thankful[l] for this beautiful hour I had spen[t] in your wonder palace, because, I have forgotten entirely all the troubles, which are caused by the hard orchestral work and which sometimes produces an unbearable feeling. I never complain about this hard life; but, as you were witness in so many rehearsals and had an opportunity to see, how difficult it was for me to bring out good performances…

Thank you [for having relieved] my heart…

The Magic Flute–particularly its performance in a multisensory, beautiful environment like Gardner’s Palace–is a balm for the soul. Sendak surely would have agreed; in a 1966 interview, he stated clearly: “I can hardly live without music.”

You May Also Like

Belle of the Opera: Gardner and Wagner

Read More on the Blog

Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak

Visit the Exhibition

Ethel Smyth: Composer and Activist

Read More on the Blog