Isabella Stewart Gardner’s last acquisition of great art sits quietly in a corner waiting to be discovered by visitors.

Chinese, Song dynasty, Guanyin, 11th century–12th century, in the Chinese Loggia

Photo: Julia Featheringill

In her will, Gardner instructed that the placement of objects in her museum never change from how it appeared at the time of her death. This devotion to constancy may give the impression Gardner was herself an unchanging personage and personality. But of course, she, like all of us, was always learning and evolving, noticing new sites and having new insights. No more so than towards the end of her life when her eyes turned more seriously towards Chinese art and Chinese Buddhist art.

When I was a child growing up in the Boston area and visiting the Gardner, the dynamic composition of John Singer Sargent’s El Jaleo captivated me. As I grew a little older, the intimate experience of my father sitting with me as we stared at the Vermeer touched me in a new way. Then it was the drawings on the second floor and letters in the glass cabinets on the third floor, under the fabric covers, that spoke to me. Now, it is her last purchase that is stirring me.

Spanish Cloister with John Singer Sargent’s painting, El Jaleo

Photo: Sean Dungan

Gardner’s interests and passions also flowed about over the years. Most striking for me, is her maturing appreciation for the arts of China. The Gardners traveled to China as part of a ‘round-the-world tour in 1883 and 1884. She was a youthful 43, and excited by Chinese ornaments and decorative arts. Things that sparkled. From her diaries, we know that while in Beijing and Shanghai, she was enthusiastically acquiring textiles, snuff bottles, silk, fans, opium boxes. “All the morning curio dealers,” she notes in a September 22 entry in Beijing. And the next day, September 23, “Saw curio dealers all day.” In time, she creatively integrated these objects into her home. Luxurious silks on the walls, opium boxes scattered on tables.

Cabinet in the Little Salon with objects Isabella collected on her travels to China and Japan

Photo: Sean Dungan

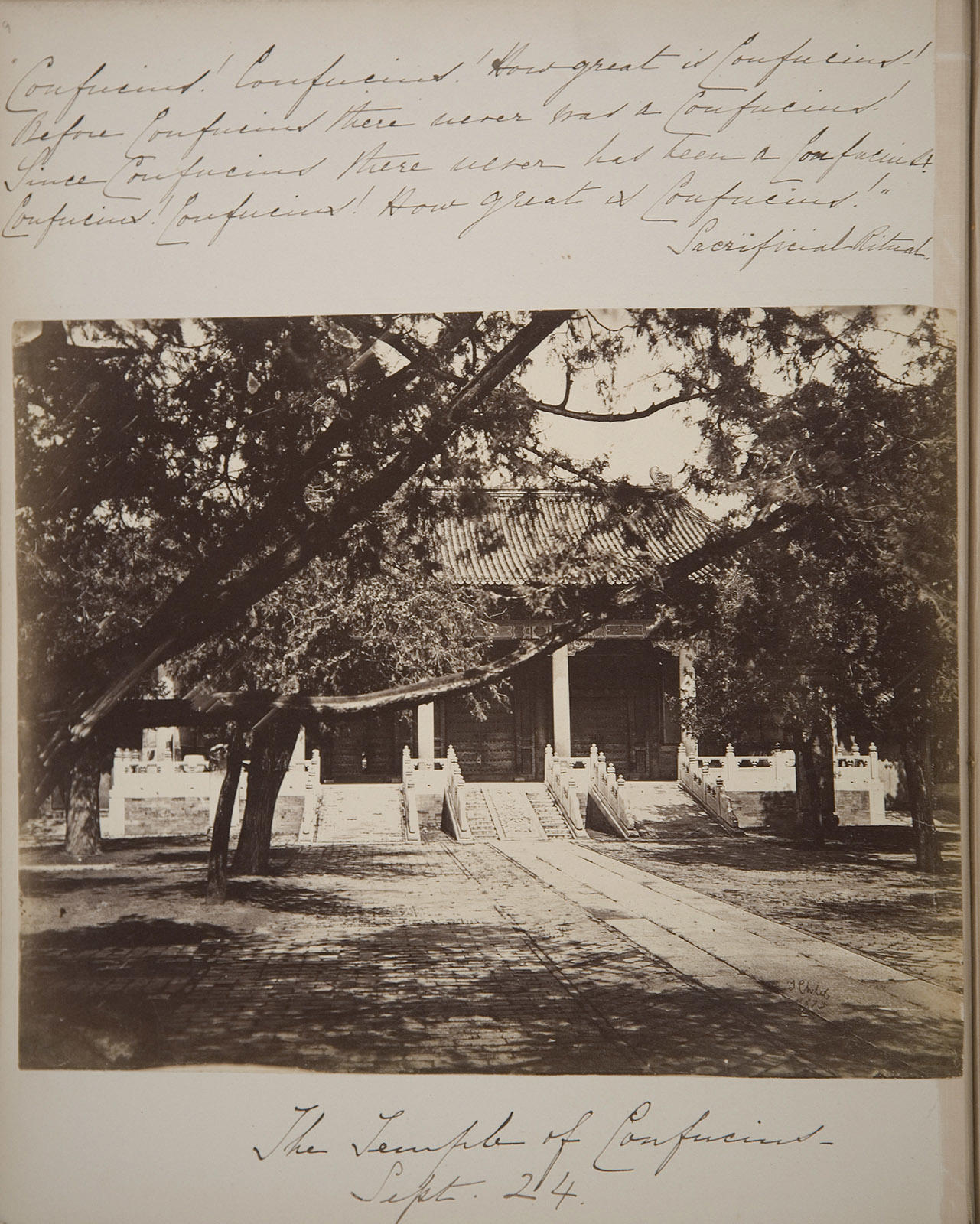

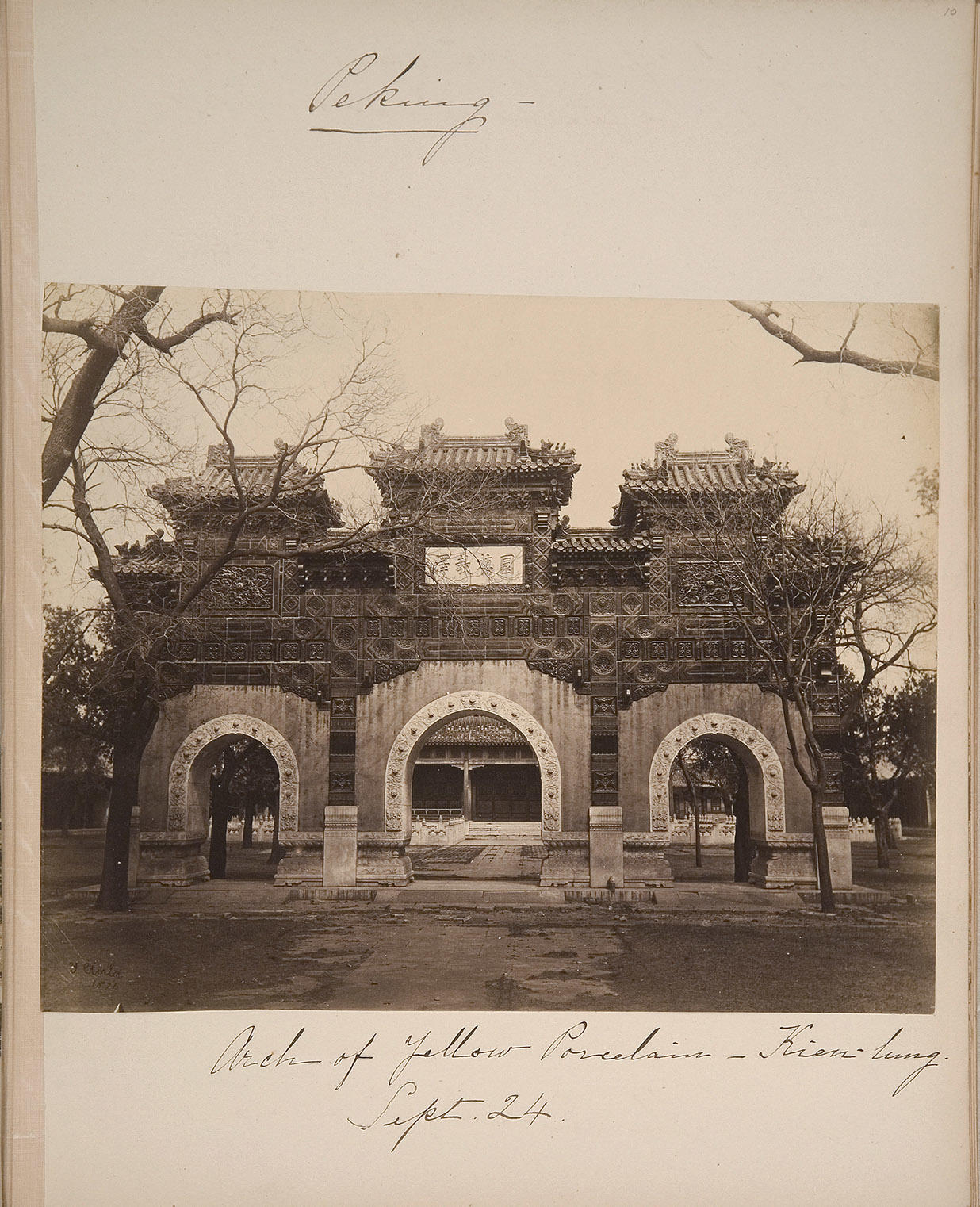

Though she was not yet collecting great art, the China trip afforded her initial and profound impressions of Chinese spiritual environments. In her travel diary on September 24 she wrote of the Lama Temple, “Strange and very interesting architecture—court after court—all the Lamas in yellow cloaks and such strange yellow hats. Services going on, one of them in an open court, consisting of odd chanting in very low voices, with an accompaniment of clapping together two pieces of wood. In one of their temples a very large gilded Buddha, standing. In another, beautiful Thibetan carpets and cloisonne altar decorations." * Impressions like these would eventually result in her creation of a resonant space in her home and as well as emotional doorway into appreciating Chinese Buddhist sculpture.

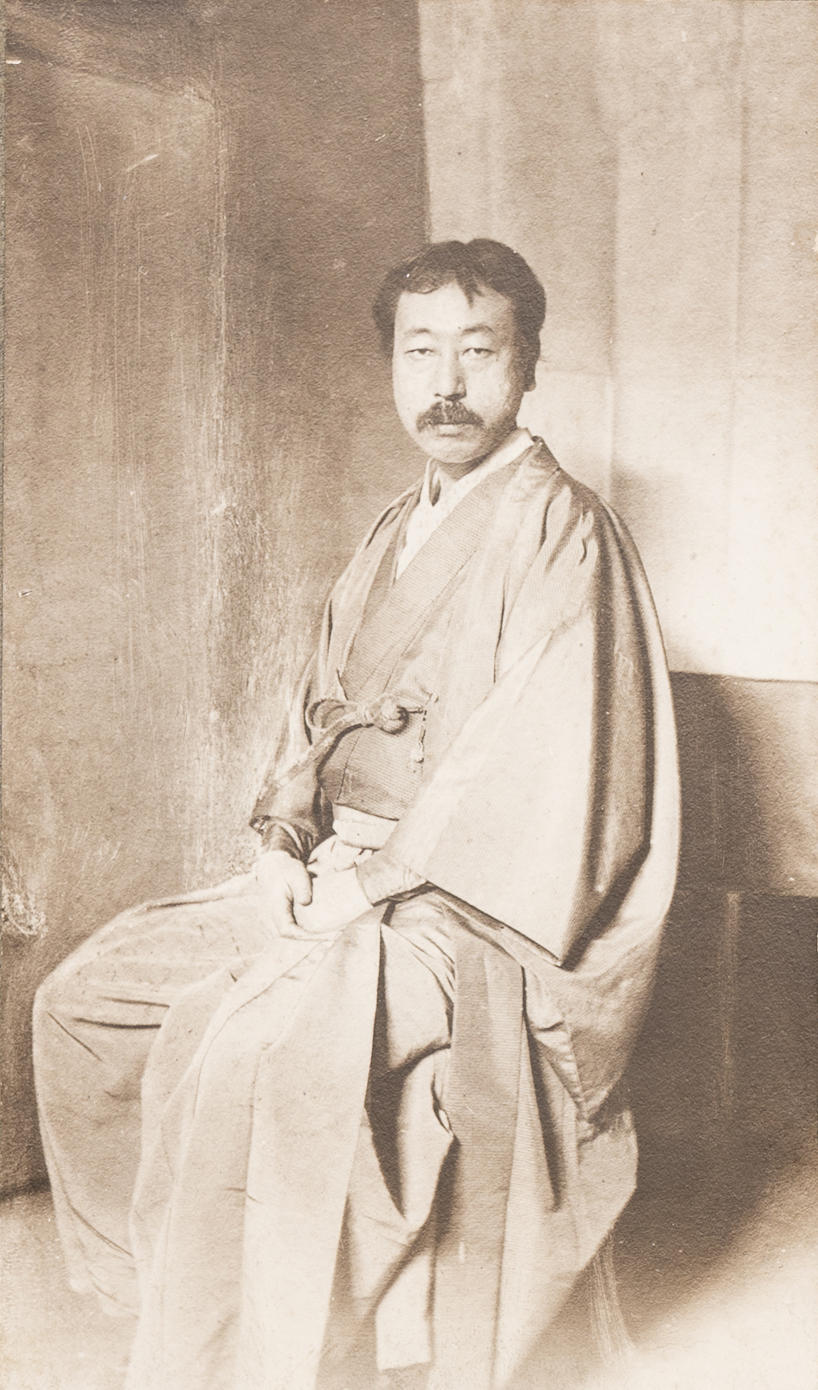

The arrival in Boston of the Museum of Fine Arts Curator of Japanese and Chinese art, Okakura Kakuzo (1863–1913) enriched Gardner’s understanding of Asian culture, religion and art. For seven years Okakura was a major figure in her aesthetic and intellectual life, until he passed away in 1913. She was, her friends reported, bereft.

Okakura Kakuzo, about 1903

Did the friendship and then loss of Okakura jolt a new depth of emotion and a subsequent search for beauty in the Asian art he had promoted? Or was it the influence of Bernard Berenson—a guide and companion for her in the world of European painting— who in the years after 1910 became fervently enamored with Chinese art. Or was it a coincidental confluence of the death of Okakura and Berenson’s enthusiasm?

How I wish I were now starting out in life! I should devote myself to China as I have to Italy.

In 1914, she created a new type of space on the first floor of her home, filling it with large gilt bronze Buddhas, altar tables and sumptuous silks. This dark, half-underground room, furnished in her own interpretation of a temple, did not encourage looking at art or even social conversation, but instead suggested internal meditations. With the passing of Okakura, the 1883 visits to temples in Asia may have been looming larger and more insistently in her mind. The moment had come to conjure up those atmospheres in her own way. It was in this room, she told Boston Mayor James Curley, she communed with her Buddhas.

This new room, which she called the Chinese Room, was not, in any manner of speaking, “authentic” to a specific locale in Asia. Religious statues standing side-by-side came from a range of cultures—China, Japan, Cambodia. Japanese screens hung on walls as background for Chinese deities. No matter. Together the objects created an atmosphere.

Chinese Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1961

In addition to the enthusiasm for creating this meditative environment, Gardner also developed a passionate appetite for early Chinese Buddhist sculpture. Okakura had acquired a number of Chinese stone Buddhist sculptures for the Museum of Fine Arts in China and Japan as early as 1907, but it was not until 1913 that such sculptures began appearing on the art market in Europe. Chinese connoisseurs, more focused on arts of the brush, had paid little attention to the stone carvings in long abandoned temples. But European and Japanese explorers stumbled upon them, proclaimed visual links to Hellenic art, and started a rage. Soon Beijing dealers were dispatching local villagers to remove heads and even whole statues from their sites. One of these, a stone votive stele, Berenson wrote to Gardner, on May 7, 1914, was “the finest thing that has come out of China.” She had to have it. She got the stele, and soon desired more. “I only wish I had more Chinese masterpieces,” she wrote to Berenson. “Now promise me to save all your money,” he replied, “and let me make you as fine a Chinese collection as you have of Italian.”

Chinese, Eastern Wei, Votive Stele, 543. Limestone

See it in the Chinese Loggia. Photo: Sean Dungan

The check for Gardner’s last Chinese work was received by the dealer on December 31, 1919, five days after her first stroke. We can only speculate whether she was able to appreciate its arrival at Fenway Court, but we do know that in these later days of her life—with her heightened appreciation for Chinese sculpture—she specifically selected it to join her in her home. The wooden, almost life-size sculpture depicts the much-adored deity Guanyin, often called the Bodhisattva of Compassion. In the Buddhist pantheon, a bodhisattva is one who, having perfected themselves, and at the cusp of entering nirvana, chooses to stay among mortals to assist them on their own roads to salvation, or nirvana. The term Guanyin is the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit Avalokiteshvara, meaning “one who observes the sounds (cries),” implying “the one who is who aware of the cries and suffering of all.” In some depictions of Guanyin, the deity has hundreds of arms to help all in need. Other versions have eleven heads so as to hear all those who are suffering.

Chinese, Song dynasty, Guanyin, 11th century–12th century. Painted wood with remains of gilding

See it in the Chinese Loggia

Specific features identify the statue as Guanyin—the crown sporting a small image of the Amitabha buddha, the teacher of Guanyin; and visual attributes of the princely class to which Guanyin was born—the necklace, the arm bracelet; and the pose. The relaxed and gentle torso, with one leg bent up supporting an outstretched arm; and the other leg hanging pendant, often referred to as the princely pose.

This wooden statue, covered with layers of pigmented lacquer and gold, most likely dates from the 12th century when devotion to Guanyin was growing in China. Over many centuries, worshippers donated funds to refresh the exterior surface. Today the many layers of time and devotion are visible. The original red skirt decorated with green and white cloud patterns, the wood below the worn away colors, and later gold embellishments to add opulence.

Chinese, Song dynasty, Guanyin (detail), 11th century–12th century

And then there is the calm repose of the face, which may have captivated Gardner. Self-assured, but focused on listening, Guanyin sits, humble, compassionate, and ready to respond to the cries of the suffering. These features, which drew in Gardner during her lifetime, still draw in viewers today.

Read More on the Blog

Isabella in China

View the Exhibition

Shen Wei: Painting in Motion

Explore the Collection

Chinese, Votive Stele, 543

* Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924), “Monday Sept. 24,” from Travel Diary: China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, India, Singapore, Myanmar, Egypt, and Italy, September 1883 to June 1884 (ARC.009111)

![Isabella Stewart Gardner's Travel Album: China, 1883 showing the Imperial Academy [Hall of Classics] in Beijing](https://www.gardnermuseum.org/sites/default/files/styles/portrait_large/public/2020-11/109817_rev.jpg)