Cafe G is closed for repairs from January 29 through February 16, 2026.

We apologize for the inconvenience.

Did you know that an omelet made from one ostrich egg is the equivalent to about 20 chicken eggs? I didn’t either, until recently when I spent several months conserving an eggshell from the 1800s. And did you know that there are three ostrich eggs on display in the Museum, one each in the first floor Macknight Room, the second floor Dutch Room, and the third floor Veronese Room? Actually, you’ll find two ostrich eggs and an emu egg because we recently discovered that one of the eggs cataloged as ostrich was indeed, absolutely, positively emu.

Collecting Eggs

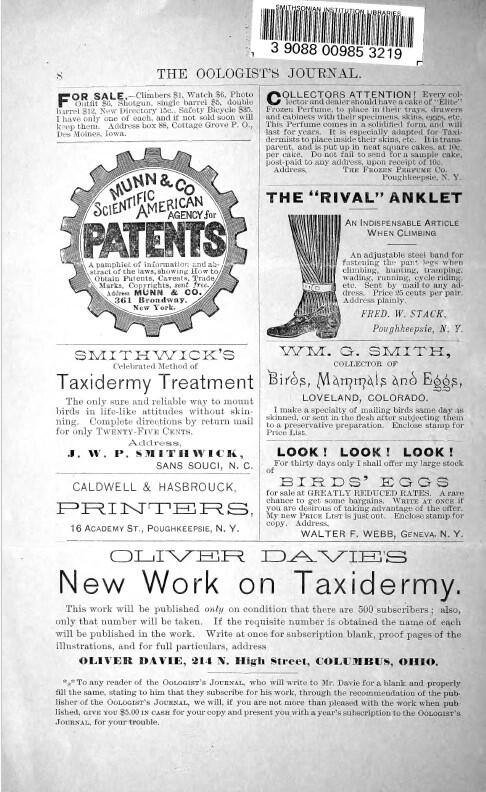

Why Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924) collected and displayed these large eggs is unknown, but we have a couple of guesses. Collecting egg specimens was a popular hobby for upper class Victorian collectors, as well as naturalists and adventurers. Publications such as The Oölogist’s Journal published articles in the 1800s with instructions for collecting and preparing bird’s eggs alongside advertisements for buying eggs from dealers.

Smithsonian Libraries (QL671 .O592)

The Oölogist’s Journal. Vol. 1, Feb. 1891, Poughkeepsie, New York, p. 8, advertising eggs for sale

Isabella may have also seen large ostrich eggs displayed in churches and mosques that she visited in her world travels. There is a tradition of suspending ostrich eggs above the iconostasis, altars, or doorways in Eastern Orthodox, including Egyptian Coptic and Greek Orthodox, churches. Sometimes these large eggs are suspended from ropes or cradled by netting made of silk or metallic threads and decorated with tassels and pom poms, or sometimes they are hung from fine metal chains.

Weltmuseum Wien, Vienna (16981, 16982, 17089, 17090)

Egyptian and Turkish, Ostrich Egg Pendants, before 1885. Ostrich eggs, silk, wool, cotton, silver thread, pigment, height max: 15 cm (6 in.)

Ostrich eggs can also be found suspended from lamps and chandeliers in mosques. Sometimes ceramic ostrich eggs were substituted for the real thing if they were unavailable.

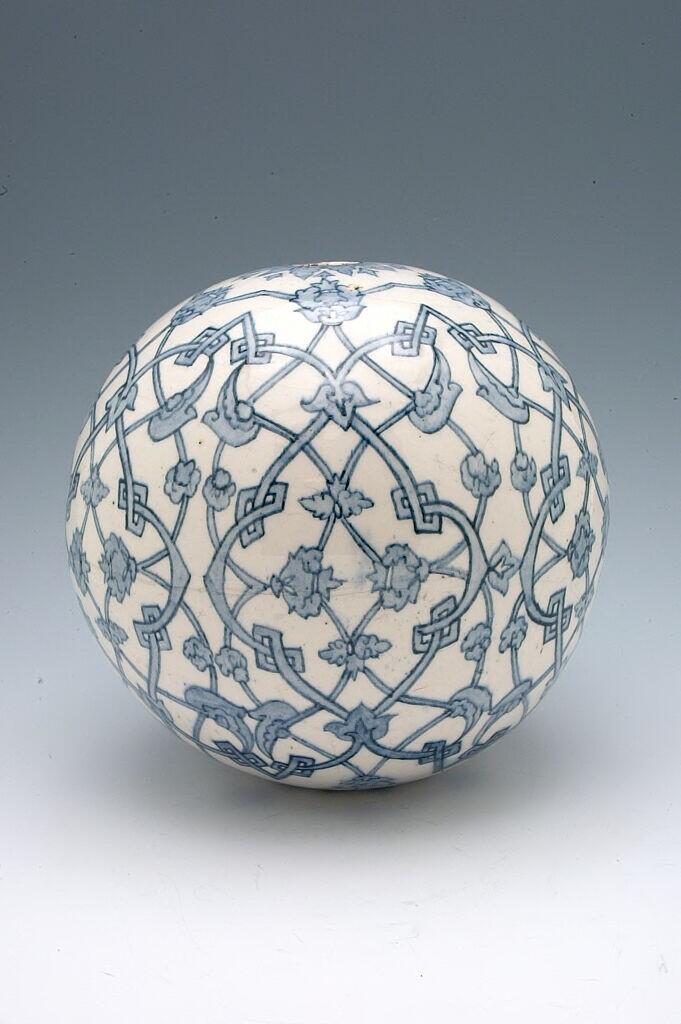

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, The Edwin Binney, 3rd Collection of Turkish Art at the Harvard Art Museums. Photo: ©President and Fellows of Harvard College (1985.331)

Turkish, Mosque or Shrine Ornament Imitating Ostrich Egg Votive Hangings, 18th century. Underglaze blue-and-white painted fritware, 21.2 cm (8 3/8 in.)

We can even see an ostrich egg hung above the Virgin and Child in Piero della Francesca’s painting, Madonna and Child with Saints, Angels and Federico da Montefeltro (San Bernardino Altarpiece) from the 1470s.

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan (180)

Piero della Francesca (Italian, about 1415–1492), Madonna and Child with Saints, Angels and Federico da Montefeltro (San Bernardino Altarpiece), 1472–1474. Tempera on panel, 251 x 175 cm (98 ⅞ x 69 in.)

The symbolism of ostrich eggs hung in churches and mosques is variously described as a symbol of birth as well as resurrection—a visual reminder to concentrate on prayer and spiritual thoughts just as an ostrich keeps a vigilant and watchful eye on its nest. Other sources say they were hung in mosques to warn of earthquakes, to prevent spiders from nesting in the chandeliers, or to prevent mice from drinking the oil in the oil lamps.

Isabella's Eggs

Whether Isabella was aware of the meaning of the ostrich egg in religious contexts or not, she displayed two large eggs in the Drawing Room of her Beacon Street home as early as 1880; one suspended from the central chandelier and the other from a candelabra on the mantle.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.010861)

Possibly John Lowell Gardner Jr. (American, 1837–1898), Drawing Room, 152 Beacon Street, Boston, 1880. Gelatin silver print, showing eggs suspended from the central chandelier and candelabra on the right side of the mantle

In her Museum, Isabella displayed the emu egg in the Veronese Room, suspended from the arm of a candelabra that flanks an elaborate installation of the Black Glass Madonna. Perhaps Isabella herself witnessed the longstanding tradition of positioning eggs near religious objects and lighting devices during her travels to the Near East, Mediterranean, and North Africa, and sought to replicate it in the museum.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The Black Glass Madonna inside a vitrine in the Veronese Room

Examining the Egg

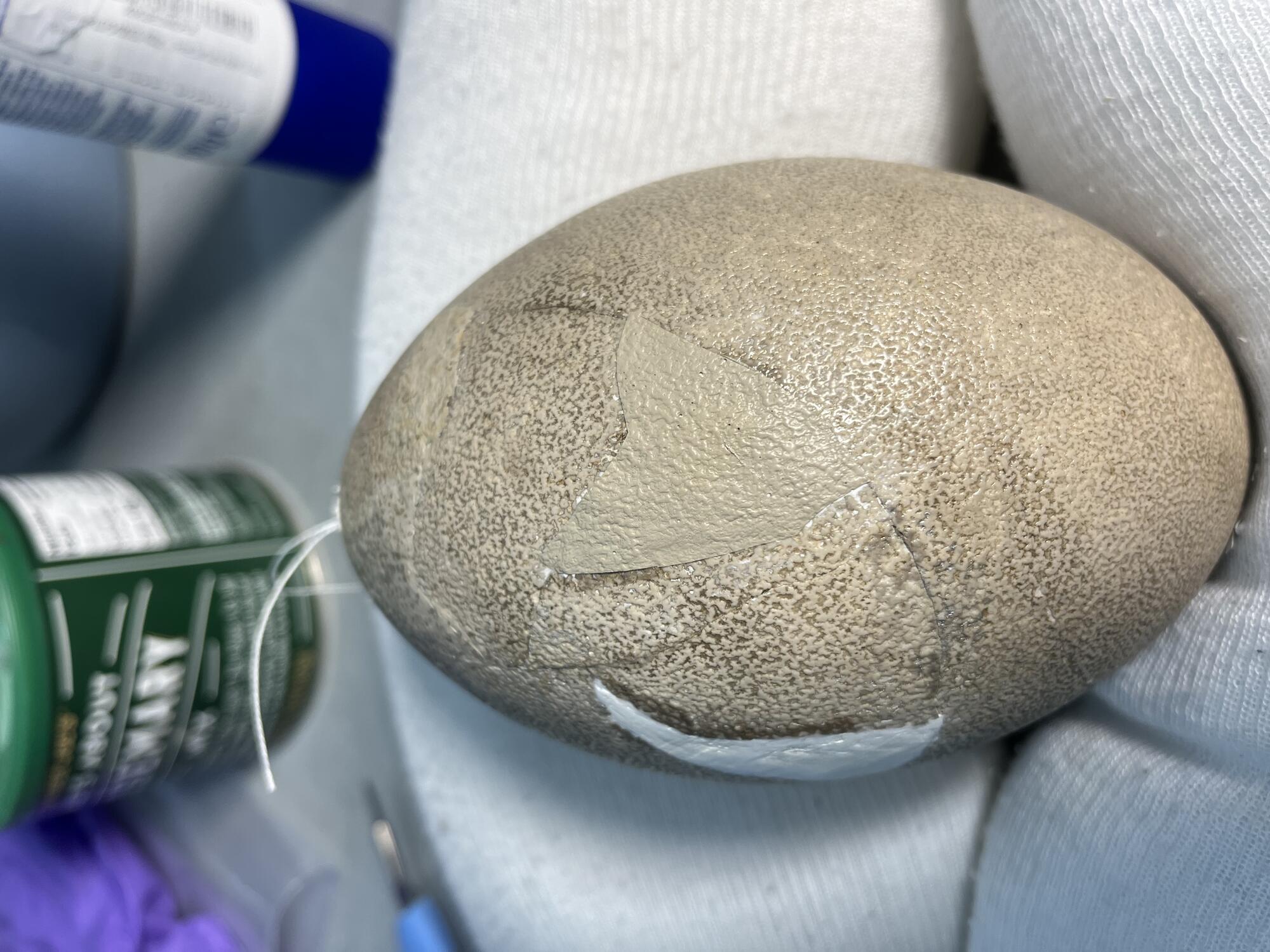

But how did we come to discover that the Veronese Room’s egg is not actually an ostrich egg, but an emu egg? While moving the egg for collection photography, our Collections Care Associate noticed that the eggshell was severely cracked, had been previously restored, and had new cracks around the bottom. Once the egg was brought to Conservation, I closely examined it and noticed that in addition to the new cracks, old cracks and fills, there was also something rattling around inside! The eggshell was also extremely dirty so staff decided to do a full conservation treatment to clean and stabilize it.

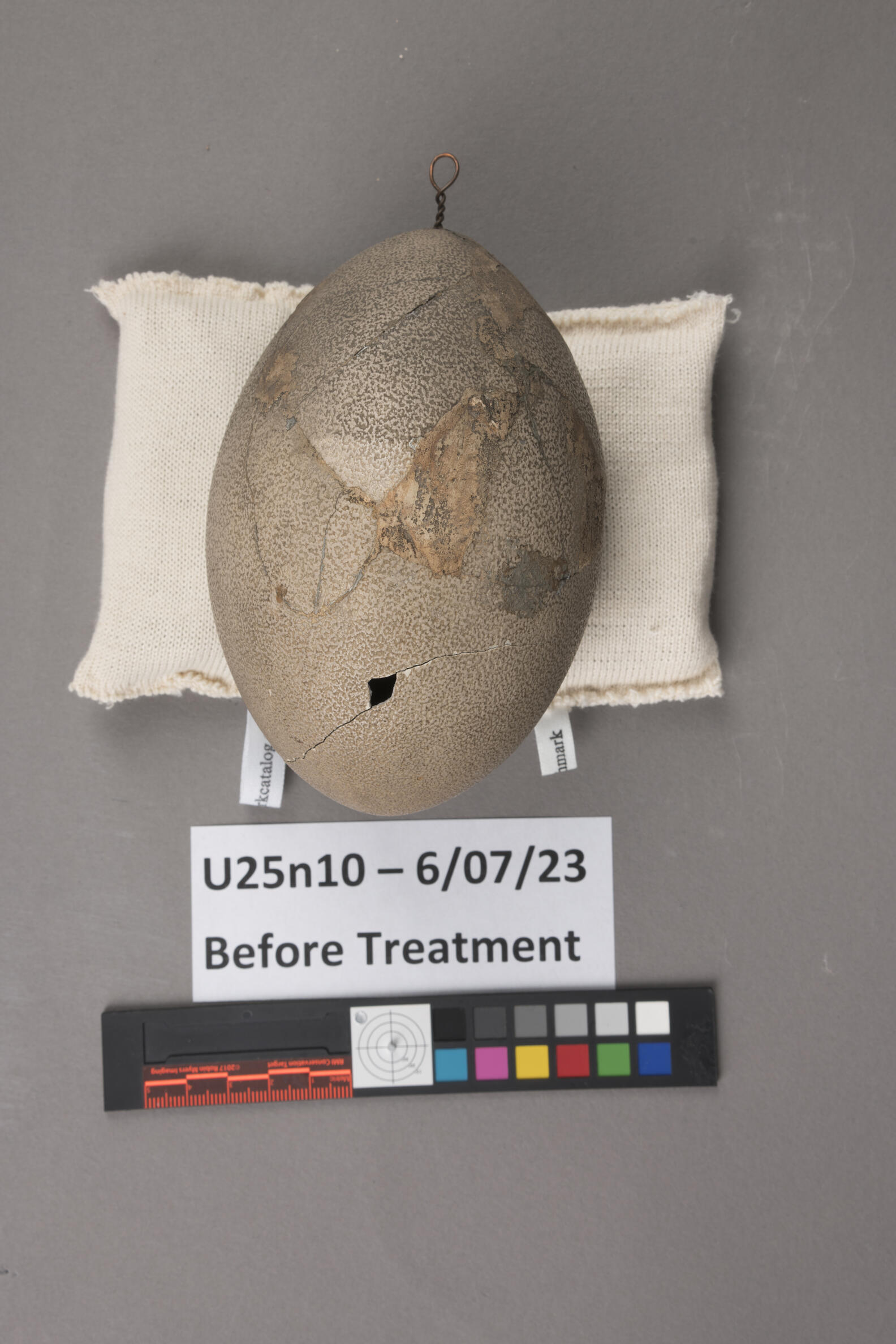

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (U25n10). See it in the Veronese Room.

Emu egg before conservation treatment. Surface is dirty and cracked with multiple plaster fills and one loss.

I began by removing the large plaster fills that were compensating for missing sections of the shell. Once the fills were out, there was access to the inside of the shell, making it possible to reach in with a pair of long tweezers to retrieve dislodged chunks of plaster, bits of wire mesh, and even some crumpled up paper.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Restoration material removed from interior of emu egg during treatment

The wire mesh bits were from a previous repair using plaster; if you’re familiar with lath and plaster walls, the metal mesh was the lath.

Identifying the Egg

During treatment, it occurred to me that while this was a large egg, it definitely was not an ostrich egg. Ostrich eggs are smooth, and this egg has a very bumpy and textured surface. But what kind of egg was it? After consulting with Google, it appeared that the two most likely possibilities were emu or southern cassowary, which are both large, flightless birds that are native to Australia. Knowing my limitations, I contacted the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ) at Harvard University. There, I connected with Jeremiah Trimble, Curatorial Associate/Collections Manager in the Ornithology Department, and he generously transported several emu and southern cassowary egg specimens from MCZ to the Gardner Museum so we could do a direct comparison. Based on the shape, size and texture of our egg, Trimble identified it as an emu egg.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Emu egg from the Museum of Comparative Zoology, the Gardner Museum’s emu egg, and a southern cassowary egg from the Museum of Comparative Zoology (left to right)

He explained that the Gardner Museum’s egg is more round-bodied and has one round and one pointed end, like emu eggs. On the other hand, cassowary eggs are narrower and more oblong and have two pointed ends. Additionally, while there is variety, emu eggs are significantly textured while cassowary eggs tend to be smoother. When fresh, both egg specimens are quite dark, emu eggs are almost black and cassowary eggs are dark/bright green. However, the pigment in both is fugitive and fading occurs quite commonly, especially when exposed to ultraviolet light. Images of Gardner’s egg from her Beacon Street home (1880–1900) show it as much darker, so it is likely that the years it has been on display in front of a window in the Veronese Room contributed to its substantial fading.

Conserving and Displaying the Egg

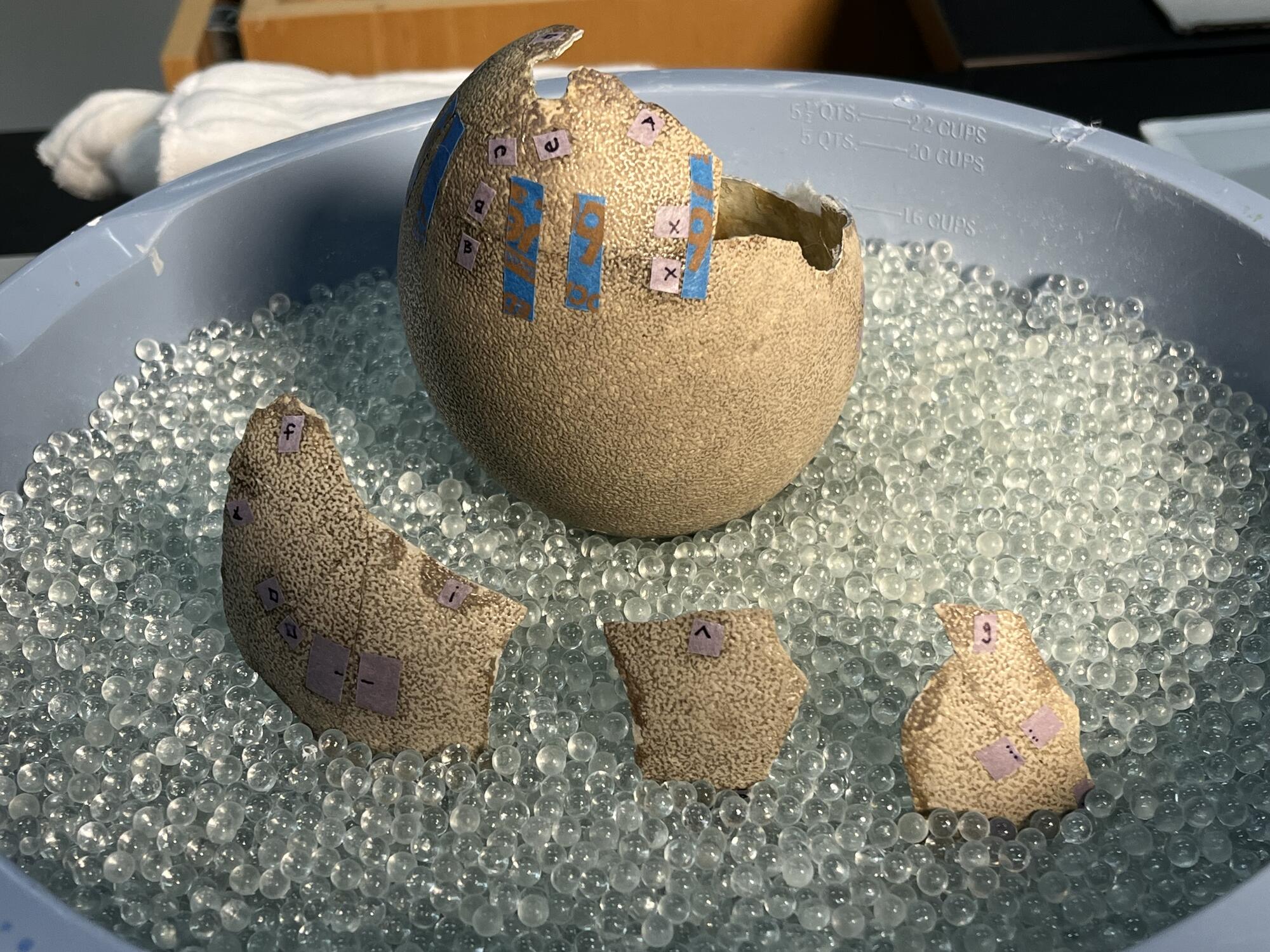

Back to the egg treatment. The egg had broken more than once and there were a lot of pieces involved. To keep track of all those pieces for reassembly I started with tiny pieces of low-tack tape on either side of the join lines, labeled with matching numbers or letters. The exterior of the shell was cleaned with a brush and some mild detergent and deionized water, and then was immediately rinsed with deionized water on cotton swabs. This removed a significant amount of dirt and grime. The eggshell was easily disassembled piece by piece using acetone and once it was fully disassembled and cleaned, it was time to put Humpty Dumpty together again.

The shell was carefully reassembled one piece at a time using a conservation-grade adhesive. The interior join lines of the shell were reinforced with strips of Japanese tissue paper that were coated with a dilute adhesive. Losses, (previously filled with plaster), were also backed with Japanese tissue coated with a dilute adhesive, which stiffened on drying, creating a sturdy backing against which I could apply the new fill material.

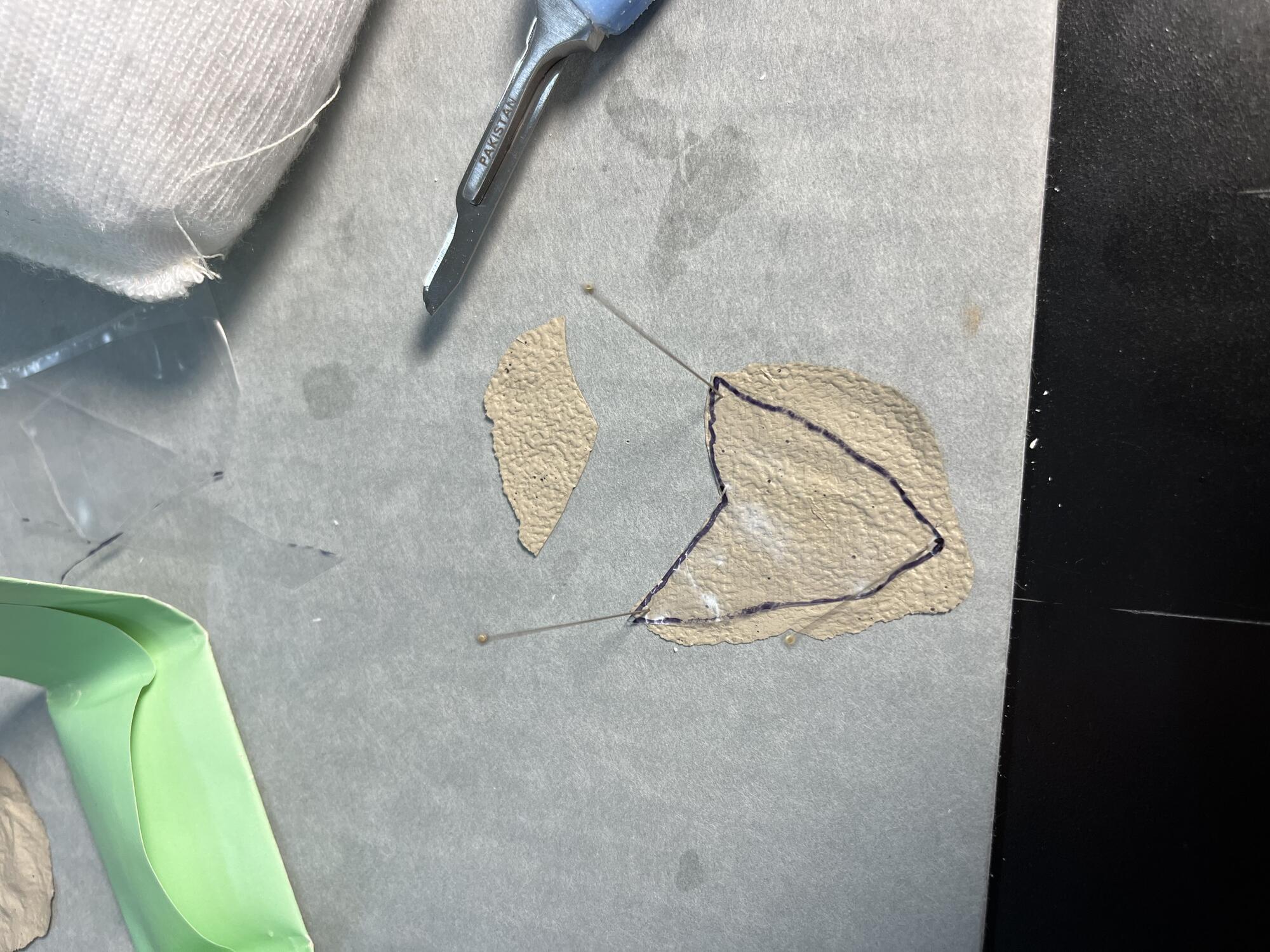

I used a custom-made spackle to fill the losses, and I took an impression of the surface texture using dental molding material. Next, I painted a film of acrylic paint into the textured mold, allowed it to dry, peeled it out of the mold, cut it to shape and glued it into place on the fills.

The last step was working with our Senior Preparator to develop a safe mount for the emu egg. Originally it was suspended from the candelabra from a copper wire that was embedded into plaster at the top of the egg. We wanted it to look like it was still suspended from a loop at the top of the egg, but in reality, we didn’t want that loop to carry the weight of the object. We devised a method using micro stainless-steel nylon-coated wire and tiny silver tube crimps that are used in jewelry making.

Although less decorative than the netting displaying ostrich eggs in some churches, our mounting system isn’t all that different. Sometimes you don’t need to reinvent the wheel!

References / Further Reading

Cordez, Phillippe. Treasure, Memory, Nature: Church Objects in the Middle Ages (Harvey Miller Publishers, 2020).

You May Also Like

Explore the collection

Ostrich, 17th century

Explore the collection

Ostrich Egg, early 19th century–20th century

Read More on the Blog

Not Your Grandmother’s Silver Cabinet