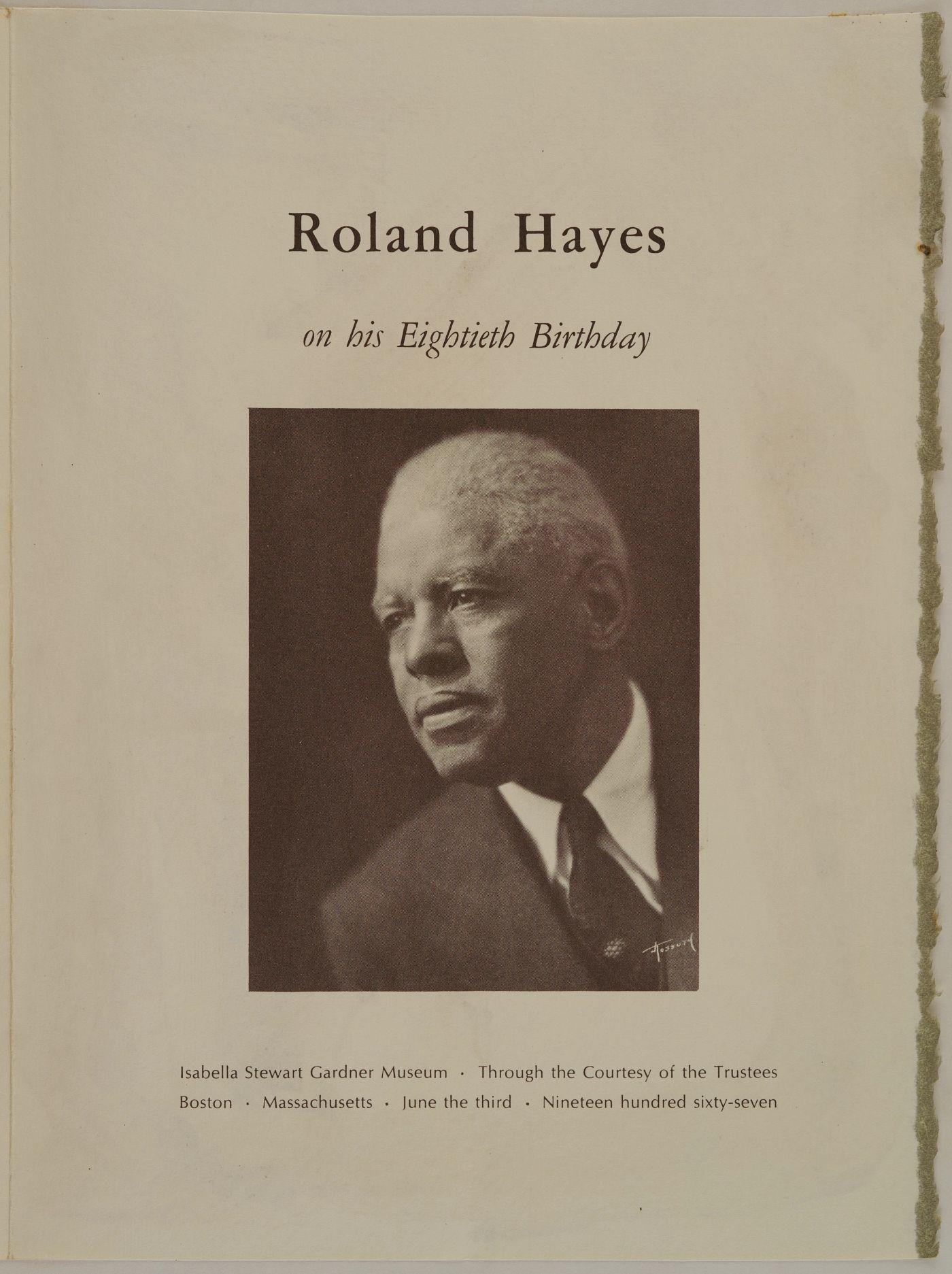

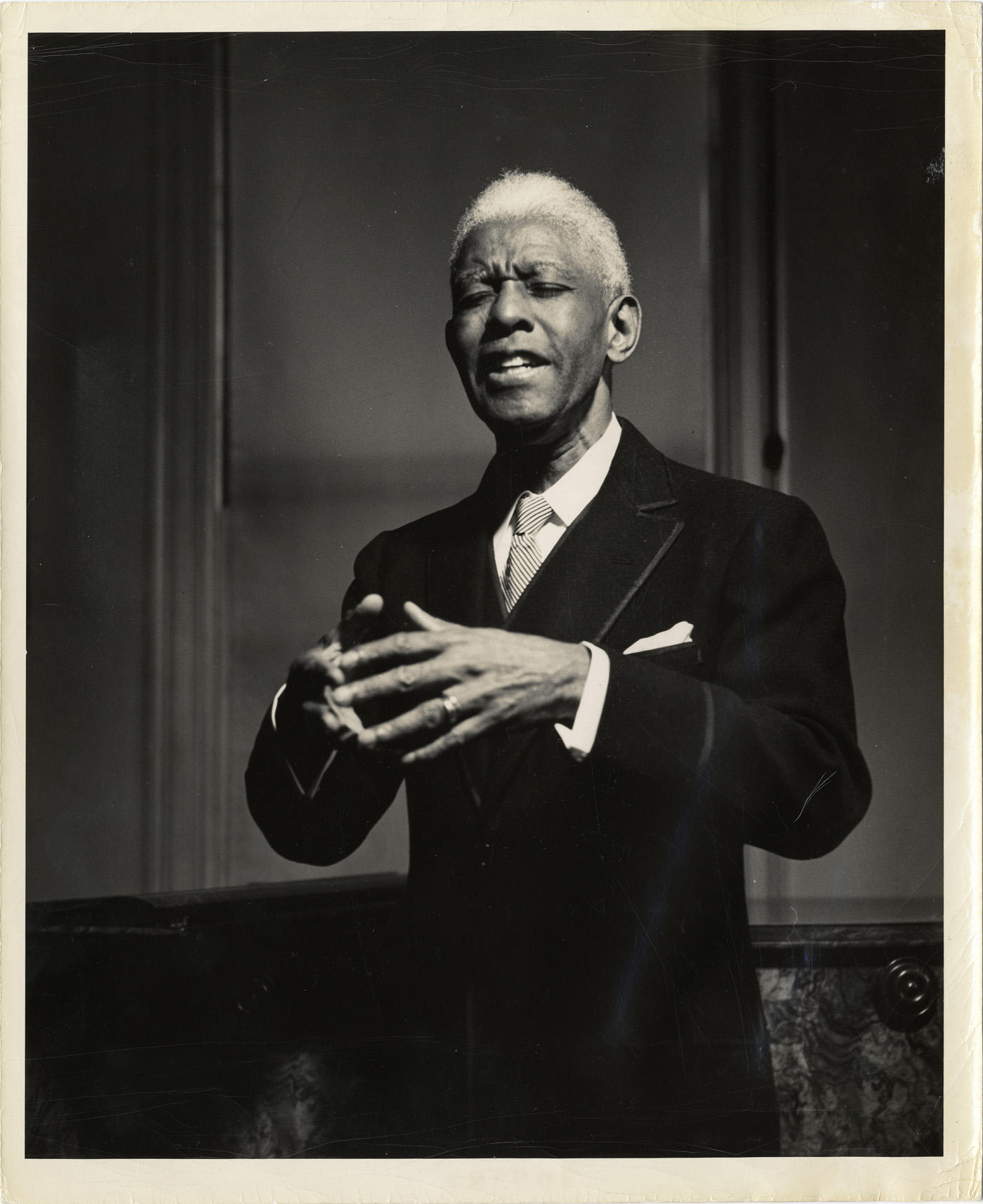

On June 3, 1967, the Boston Globe reported that the voice of Roland Hayes, famous tenor and longtime Boston area resident, resonated through the Tapestry Room. His voice, with “its sweet strength piercing the long crowded gallery of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s palace, where he first sang for her half a century ago.”¹

Hayes’ 80th Birthday Party

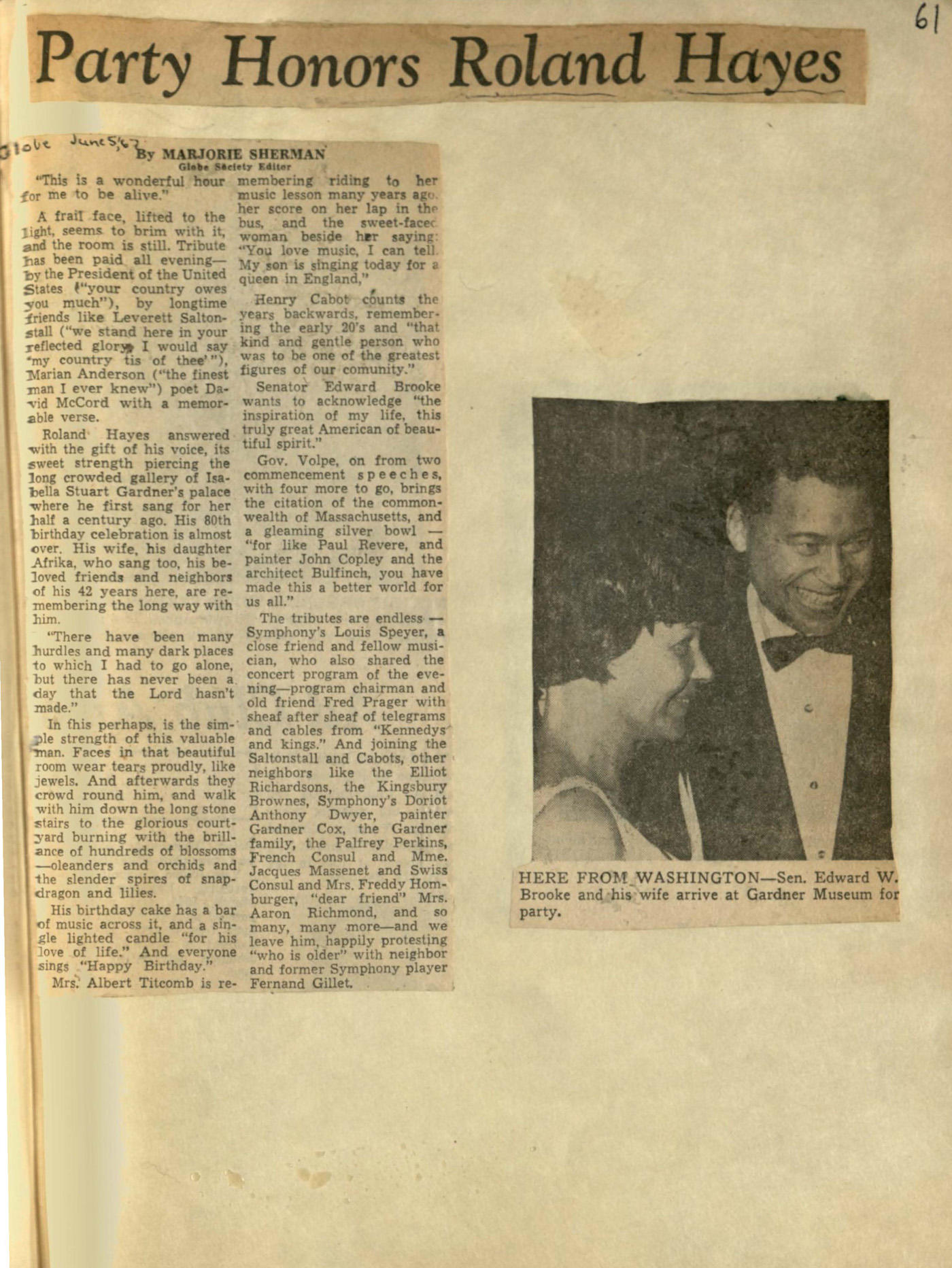

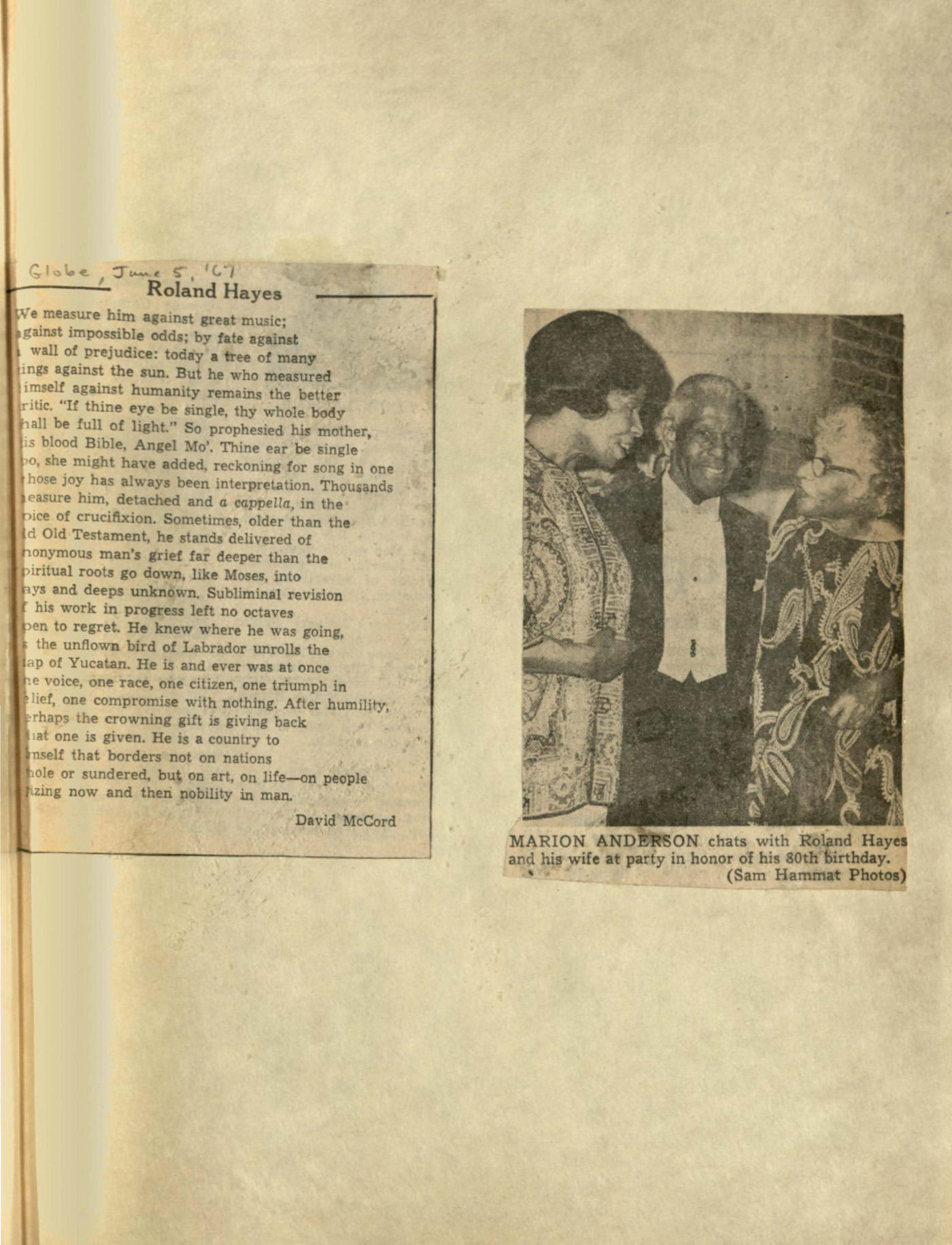

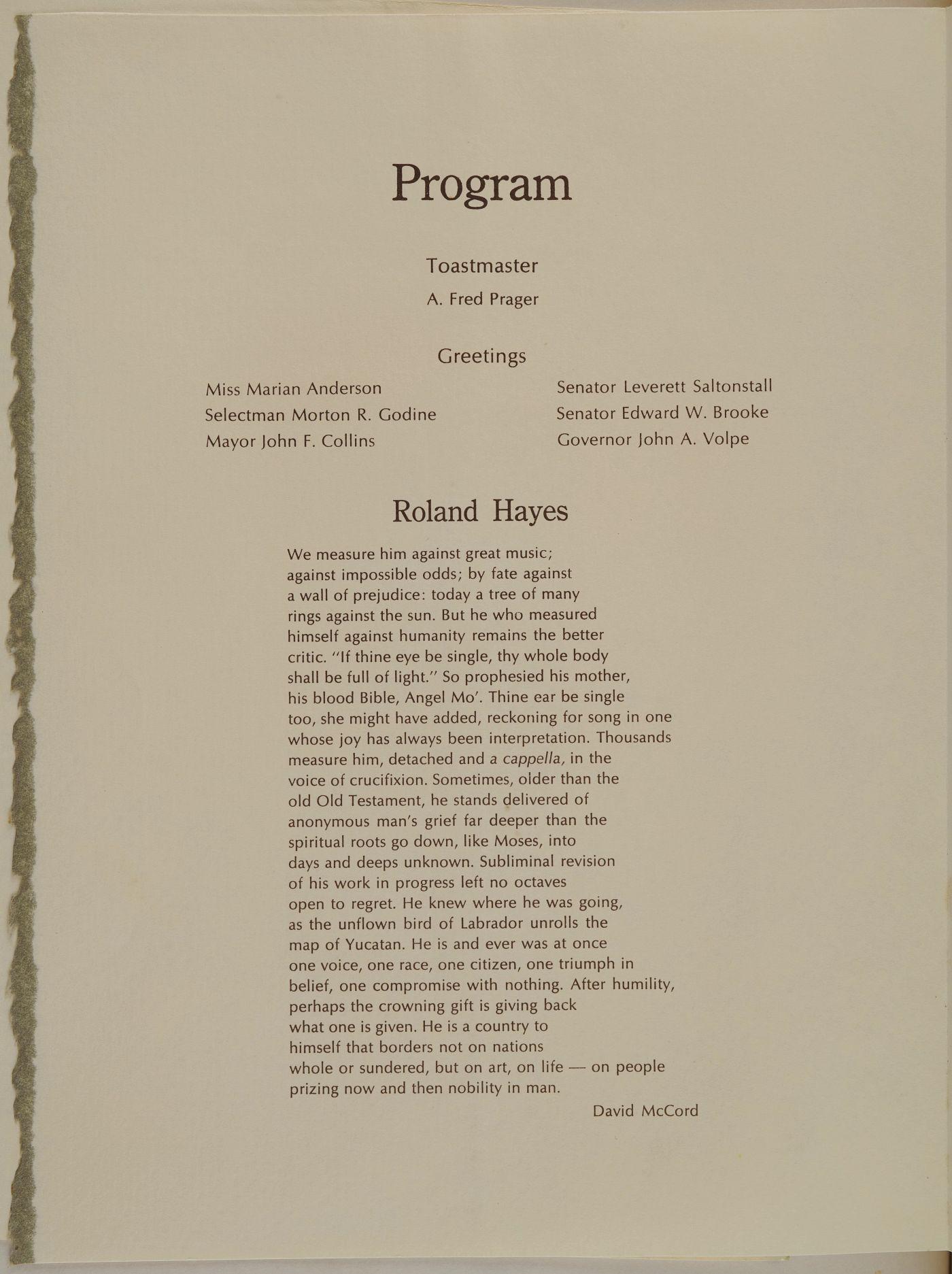

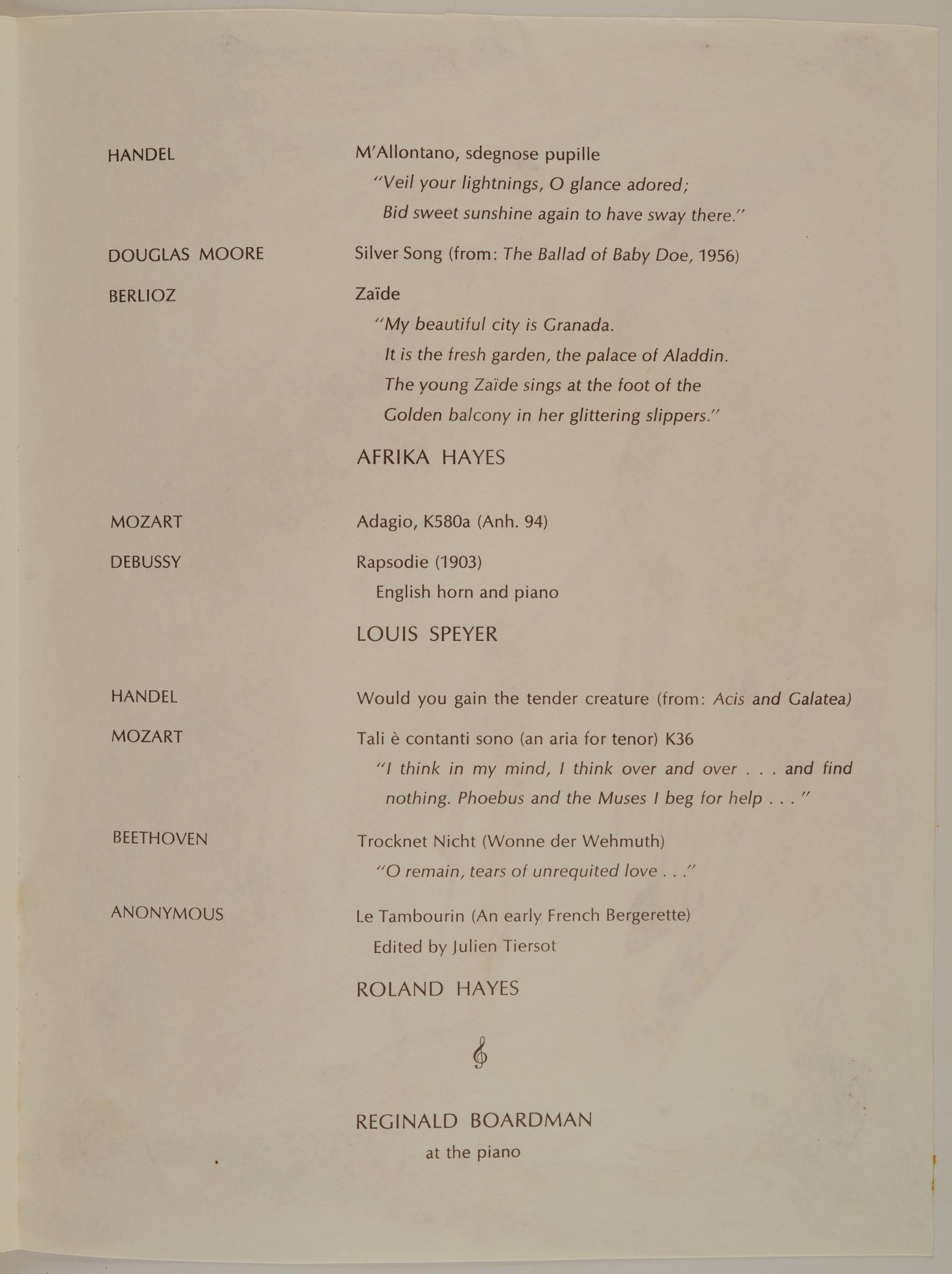

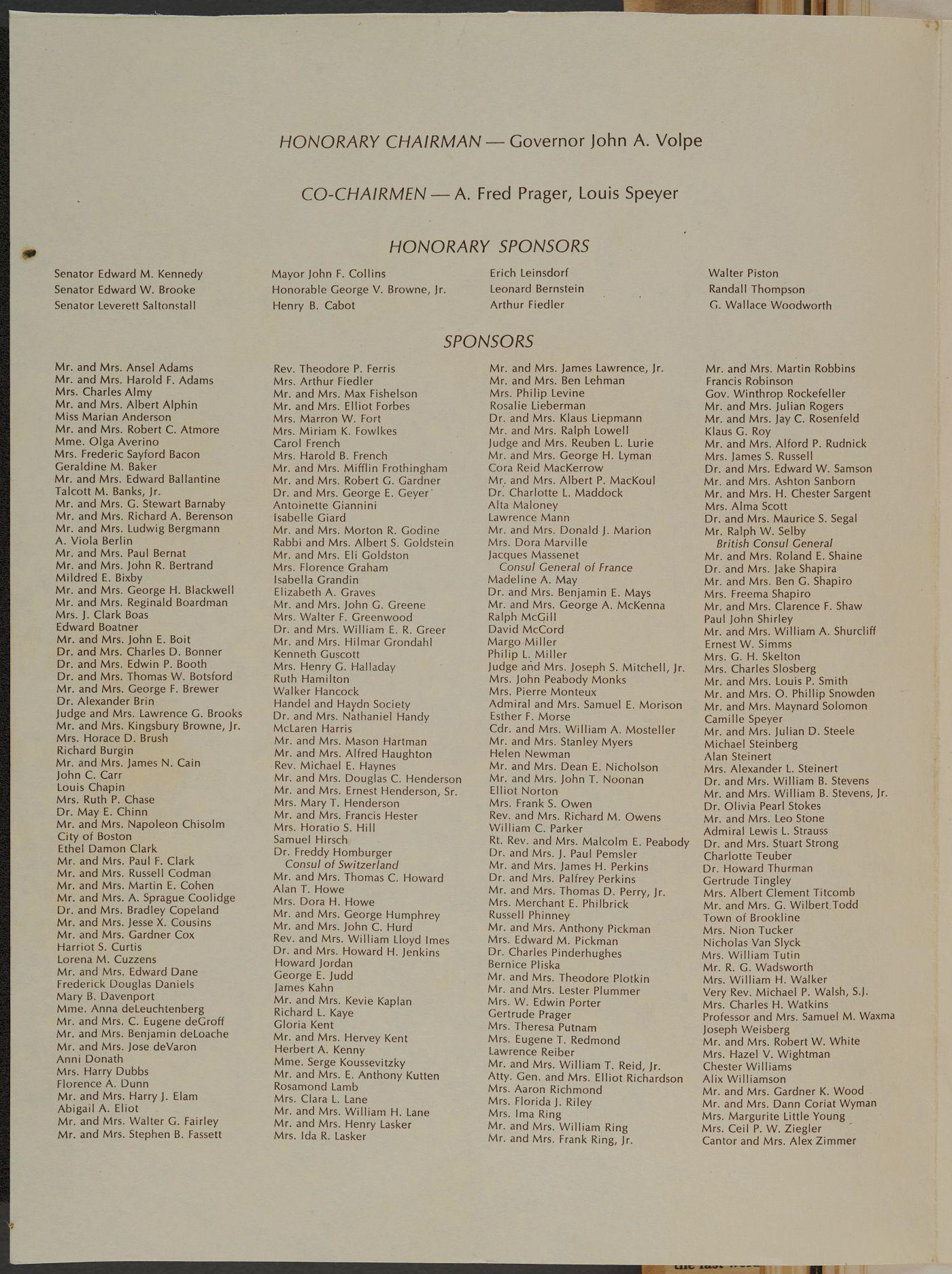

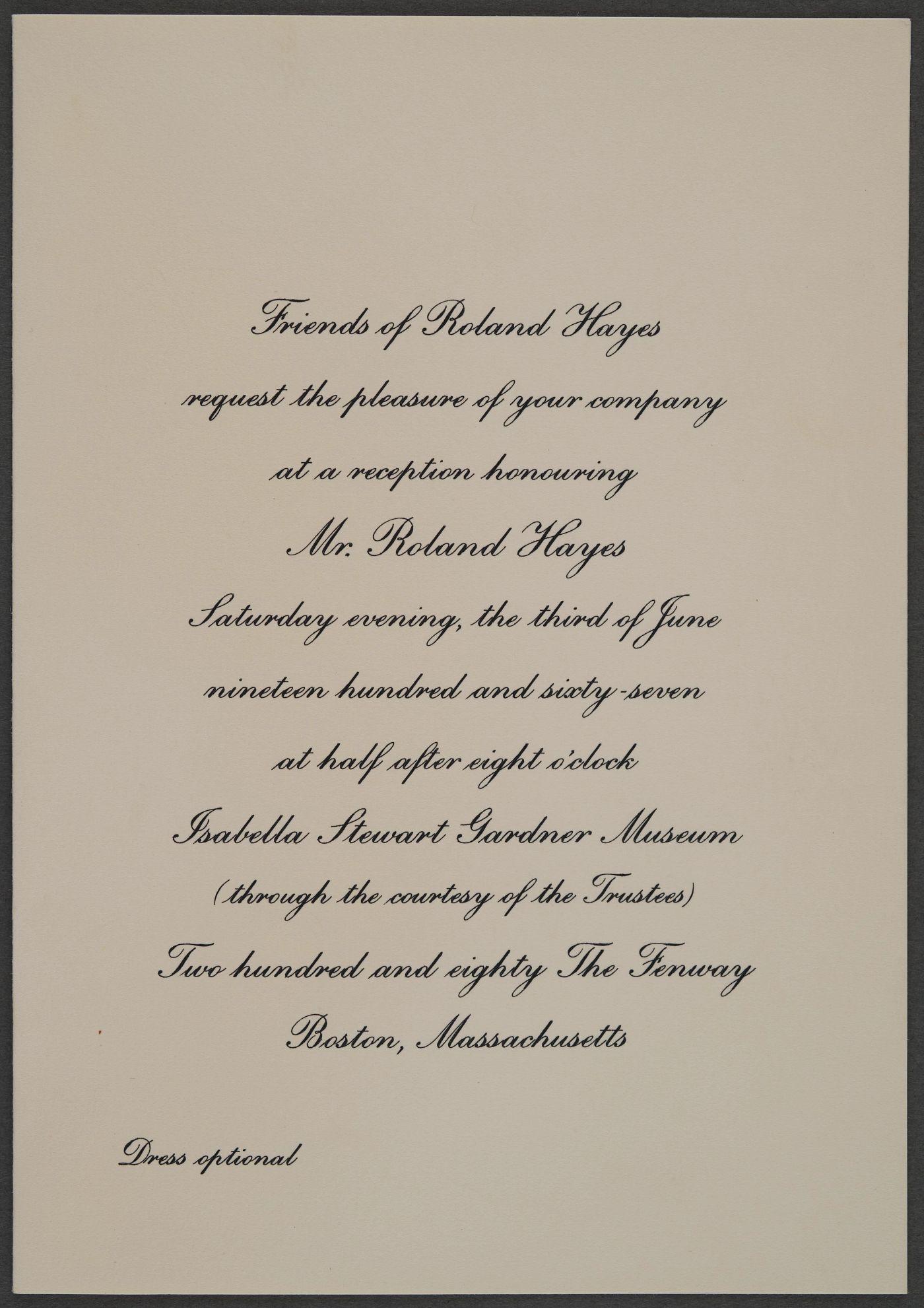

Hayes performed works by Mozart, Beethoven, and Debussy, and two African American spirituals as part of the celebration of his 80th birthday. Guests included Hayes’ long time friend and mentee, opera singer Marian Anderson, Governor John A. Volpe, and State Senator and first African-American elected to the United States Senate, Edward Brooke. Brooke praised Hayes’s talent, advocacy for the arts, and his work to break the color line in classical music. He shared that Hayes was “the inspiration of my life, this truly great American of beautiful spirit.”² President Lyndon B. Johnson wrote a letter for the occasion telling the singer “your country owes you so much.”³ The poet David McCord read an original poem entitled Roland Hayes.

We measure him against great music; against impossible odds; by fate against a wall of prejudice: Today a tree of many rings against the sun…

Hayes’ Early Life and Debut in Boston

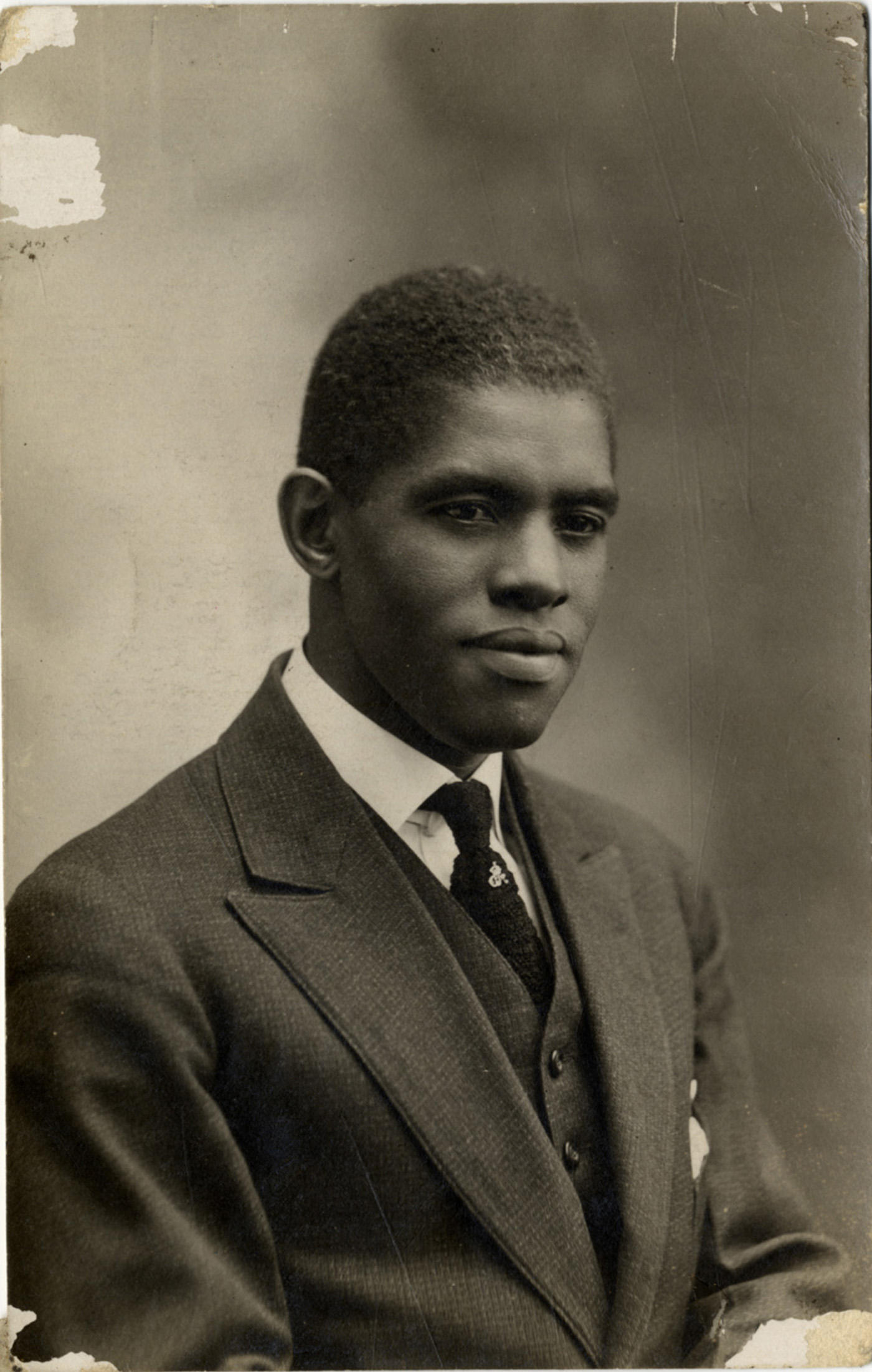

Hayes traveled a long road to being feted at the Gardner Museum, a tribute to his talent and determination. Born on June 3, 1887 in Curryville, Georgia, his parents Fanny and William Hayes worked as tenant farmers near the area where Fanny had been previously enslaved. Hayes first learned to sing spirituals as a member of the Zion Church choir. In 1905, he enrolled at Fisk University in Tennessee where he furthered his studies in voice, and joined the prestigious Fisk Jubilee Singers and traveled around the country singing spirituals to raise money for the college.

After a performance in Boston, Hayes decided to stay and pursue a career as a vocalist in the city’s busy classical music scene. With a contact in the city, he was able to find work and housing, and studied with singer Arthur Hubbard. Hayes took lessons at his teacher’s home “in order to avoid upsetting the white voice students at Hubbard's studio.”⁴

The song I sing is nothing. But what I give through the song is everything. I cannot put into words what I try to do with this instrument that is nearest to me—my voice. If I were to frame it in words, I would lose some of the ability to make it effective.⁵

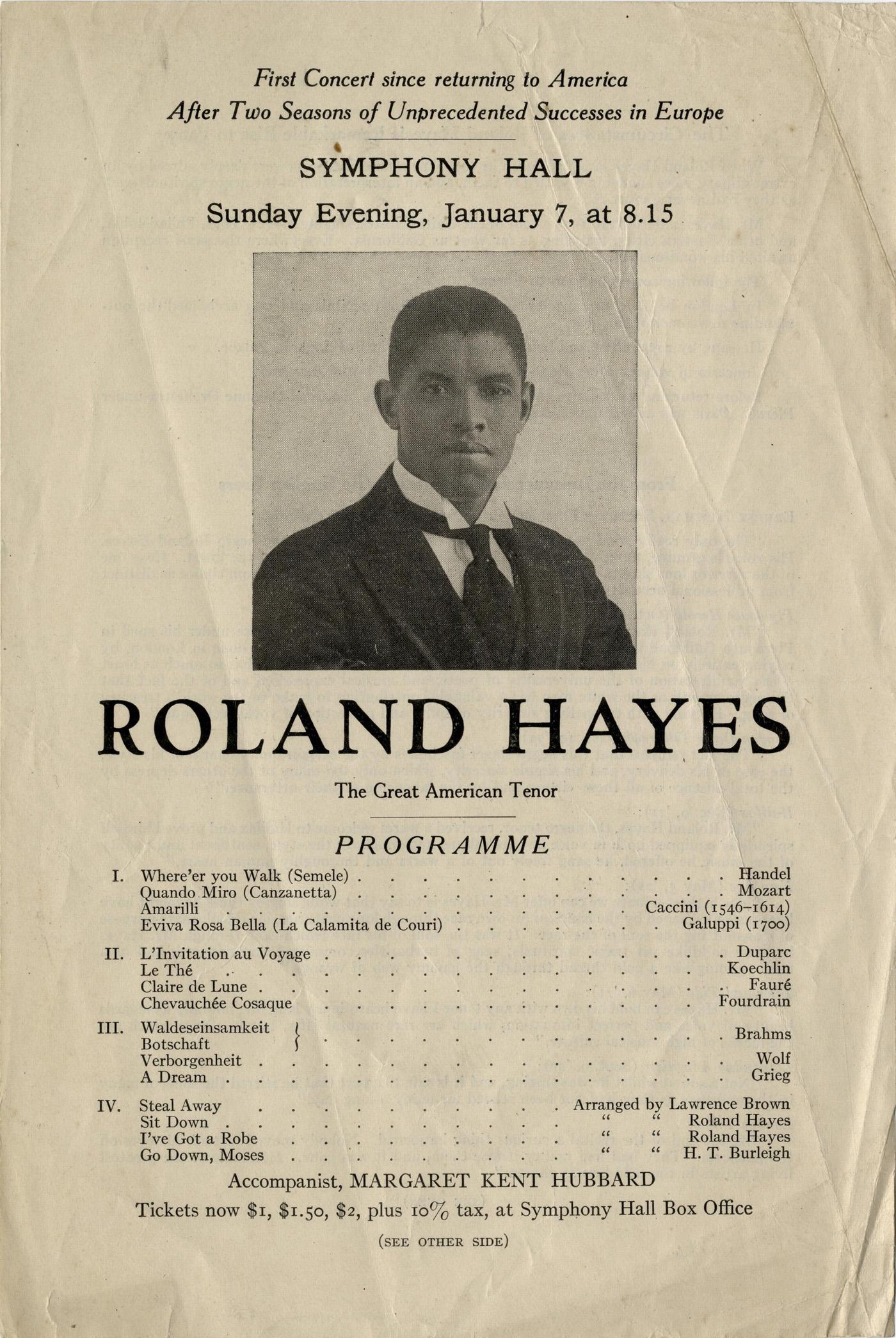

His first recital at Jordan Hall in 1912 was a success, and subsequent performances sold out as he gained critical success with his trio and as a solo artist locally and nationally.

Hayes’ performance for Isabella Stewart Gardner

The specifics of Hayes’ 1917 performance for Isabella Stewart Gardner are unknown. Isabella Stewart Gardner was an active participant in the Boston music scene, as a patron and as an enthusiast, and would likely have been interested in the success of the aspiring young tenor who was gaining fame in the city with his talent for classical songs and spirituals. Gardner had an appreciation for the African-American spirituals that Hayes incorporated in his concerts. In 1915, musician Percy Grainger writes to Gardner, “I am sending you four of the Negro choruses by Negro composers you were interested in at our last delightful meeting.” In response, she thanked Grainger, noting “You are very kind to remember I cared about that music.”⁶

Breaking the Color Barrier

What is clear is that 1917 was a pivotal year for Hayes. As a young Black performer, Hayes did not have the same access to performance spaces as his white peers. Boston did not have formal segregation laws, but was informally segregated by class and race. Hayes rented all of the venues for his performances himself, and often at a financial loss.⁷ In need of a larger venue to showcase his talents, he rented Symphony Hall in 1917. In preparation for the concert, he did his own publicity—took out newspaper ads, networked, and even used the phone book to call Bostonians to promote the concert.⁸ His efforts worked, and he performed to a sold out hall. Hayes presented a program that showcased his talents; works by European composers Handel, Mozart, Brahms, as well as African-American Spirituals by his friend, Black composer and arranger Harry T. Burleigh. The concert “placed Roland among Boston’s elite musicians and made those who doubted his ability to draw a major audience take a second look.”⁹

E. Azalia Hackley Collection, Detroit Public Library.

From there, Hayes’ career took off—he went on to perform in Europe, where he sang for sold out crowds and King George V of England. Upon his return, he became the first Black soloist to ever perform with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1923. Reflecting on this moment in his career, in advance of his eightieth birthday, Hayes said that this historical performance with the Symphony “purged tradition of a blot, the removal of which opened wide the door of opportunity to worthy artists of the Negro race.¹⁰”

Hayes’ energy and ambition did not fade as he became an octogenarian. The party at the Gardner finished in the Cloisters around the Courtyard, where guests sang “Happy Birthday.” The cake was lit with a single candle to symbolize Hayes’ continuing “love of life”¹¹ and optimism. With his characteristic optimism, he said to the guests “there have been many hurdles and many dark places to which I had to go alone, but there has never been a day that the Lord hasn’t made.”¹²

Photograph by John Brook. E. Azalia Hackley Collection, Detroit Public Library.

It was an honor for the museum to host a celebration of the life of this trailblazing artist in the history of music and beyond.

Thanks to the Special Collections Department of the Boston Public Library for research assistance, and to the Detroit Public Library for use of images from the E. Azalia Hackley Collection.

You may also like

Read More on the Blog:

Sole American Music: Spirituals During Isabella’s Time

Watch Programs Online

Witness: Spirituals and the Classical Music Tradition

Learn about Isabella

History of Music

¹ Marjorie Sherman, “Party Honors Roland Hayes,” Boston Globe, 5 June 1967.

³ Ibid.

⁴ Christopher Brooks and Robert Sims, Roland Hayes: The Legacy of an American Tenor (Indiana University Press, 2015), p.30.

⁵ Laura Haddock and Roland Hayes, “My Song is Nothing : Roland Hayes Calls his Voice the Tool of a More important Mission–Racial Harmony,” The Christian Science Monitor, 27 November 1947.

⁶ Letter from Isabella Stewart Gardner to Percy Grainger, 7 December 1915. Grainger Museum, University of Melbourne.

⁷ Brooks and Sims 2015, p. 40.

⁸ Ibid.

9 Ibid.

¹⁰ Michael Steinberg, “The Real Meaning of Great Man’s Birthday,” Boston Globe, 28 May 1967.

¹¹ Ibid.

¹² Ibid.