In 1920, John Singer Sargent, acclaimed painter and Isabella Stewart Gardner’s close friend, wrote her a note saying that he’d spent the previous evening “listening to a delightful little couple called Murphy who sing negro spirituals. Some day you must hear them.” This affluent white couple, Gerald and Sarah Murphy, did sing spirituals for Isabella and a few musical friends on 12 May 1921 in the Tapestry Room. Following their visit to Fenway Court, the Murphys gave her a book of these songs accompanied by a note: “We are so gratified at the thought that you wish to know more of these spirituals, and we enjoyed so singing them to you.”

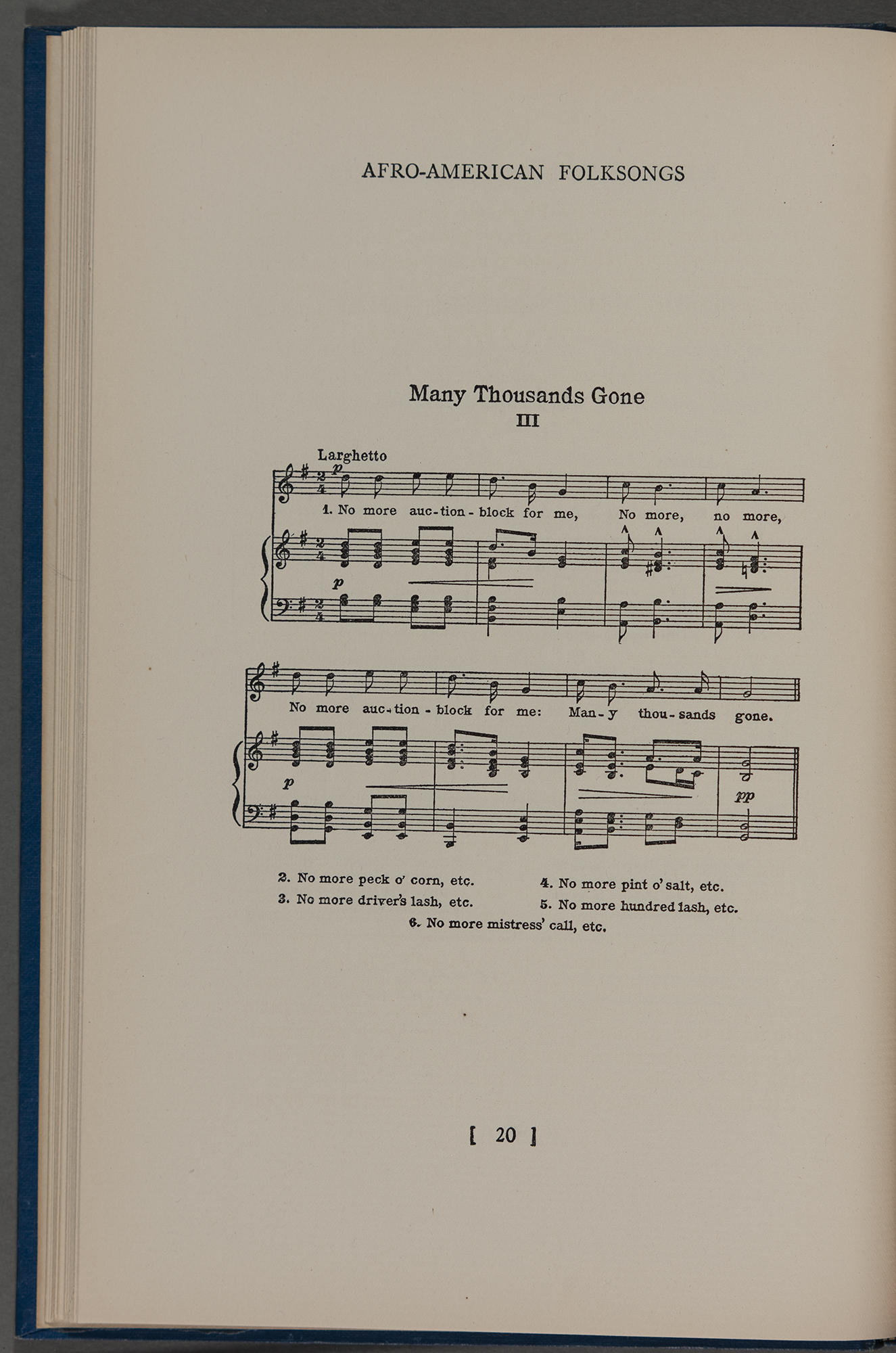

Isabella’s introduction to spirituals came at a time when the genre was reaching a larger audience than ever before. Since the rise of groups like the Fisk Jubilee Singers in the late nineteenth century, spirituals were becoming popular fixtures on the concert stage, and collections like the one Isabella owned were beginning to be published.

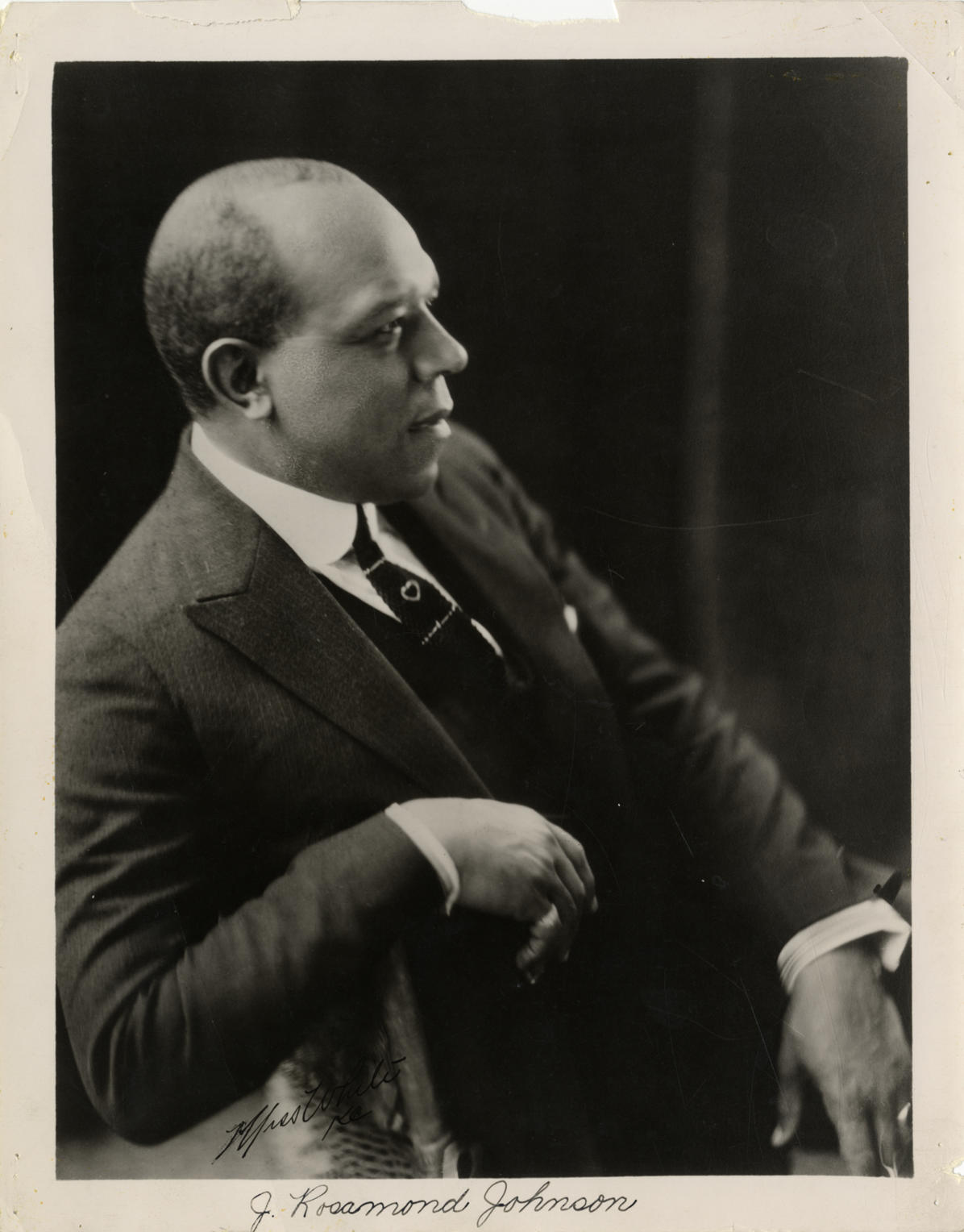

Prior to her first encounter with spirituals, Isabella had some exposure to popular entertainment by Black composers and performers. She admired The Red Moon, a successful all-Black musical theater show created by Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, whose depictions of Black and Native American characters were more sophisticated and less stereotyped than much of the entertainment of the time.

Johnson was especially inspired by spirituals, and he went on to publish The Book of American Negro Spirituals with his brother, writer and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson, in which they described the genre as “America's only folk music, and, up to this time, the finest distinctive artistic contribution she has to offer the world.”¹

Book of songs from Cole & Johnson’s “The Red Moon”

Public domain, via Arizona State University digital repository

When Isabella heard spirituals for the first time, they were concert arrangements sung by a wealthy white couple far removed from these songs’ origins in terms of race, class, and experience. The performance was restrained, and Sargent advised Isabella that the Murphys’ “voices are quite small and it is rather a sotto voce performance, so you ought to sit on top of them.”

Gerald and Sara Murphy at Cap d’Antibes Beach, 1923

Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Isabella wasn’t the only one hearing spirituals performed in contexts and styles far removed from the genre’s roots. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, polished choirs at Black universities pioneered spirituals as concert repertoire. The Fisk Jubilee Singers were the first group of this kind. According to former Fisk Jubilee singer Ron Spearman, “the spirituals that we sang were simple” and the singers were taught “to get away from any loud singing, any overindulgence of any one person in the group.”² By adopting a musical approach closer to the unembellished style of European concert music, these groups developed a novel musical form merging Black and European influences.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, 1875

National Portrait Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, Black American leaders and intellectuals were affirming the importance of spirituals to America’s musical identity. In the preface to a collection of spirituals arranged by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Booker T. Washington wrote, “The music of these songs goes to the heart because it comes from the heart.”³

The Negro folk-song…stands today not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas.

Classically-trained Black composers took up the calls to use spirituals as the basis for a new American classical musical tradition, developing new compositional styles and sounds. In the first half of the twentieth century, Harry T. Burleigh, Margaret Bonds, Nathaniel Dett, Betty Jackson King, and others wrote and published their own arrangements of spirituals. They were performed and popularized by legendary singers like Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Leontyne Price. Spiritual themes also formed the basis for new sweeping symphonic compositions.

Castle of our Skins performing in the Dutch Room of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2021

Courtesy of Bearwalk Cinema

Generations of composers have continued to reinvent and reimagine material from spirituals through the present day. In March 2021, we’ll be launching the first installment of a new series of free digital programs that explore the seismic impact of spirituals on American classical music. Featuring works for string quartet performed by local Boston group Castle of our Skins, these programs explore how Black American composers have drawn inspiration from spirituals in wide-ranging and inventive ways to forge a uniquely American sound. We invite you to dive deeper into the musical legacy of spirituals by checking out each of the four short films, released each month from March through May.

Learn More

History of Music at the Gardner

Watch a Performance

Davóne Tines performing Florence Price’s “Song to the Dark Virgin”

¹ James Weldon Johnson, ed. The Book of American Negro Spirituals (New York, 1925), p. 13.

² “The Fisk Jubilee Singers and the Concert Spiritual Tradition,” Wade in the Water, NPR, 1994.

³ Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Twenty-four Negro Melodies (Boston: 1905), p. ix.