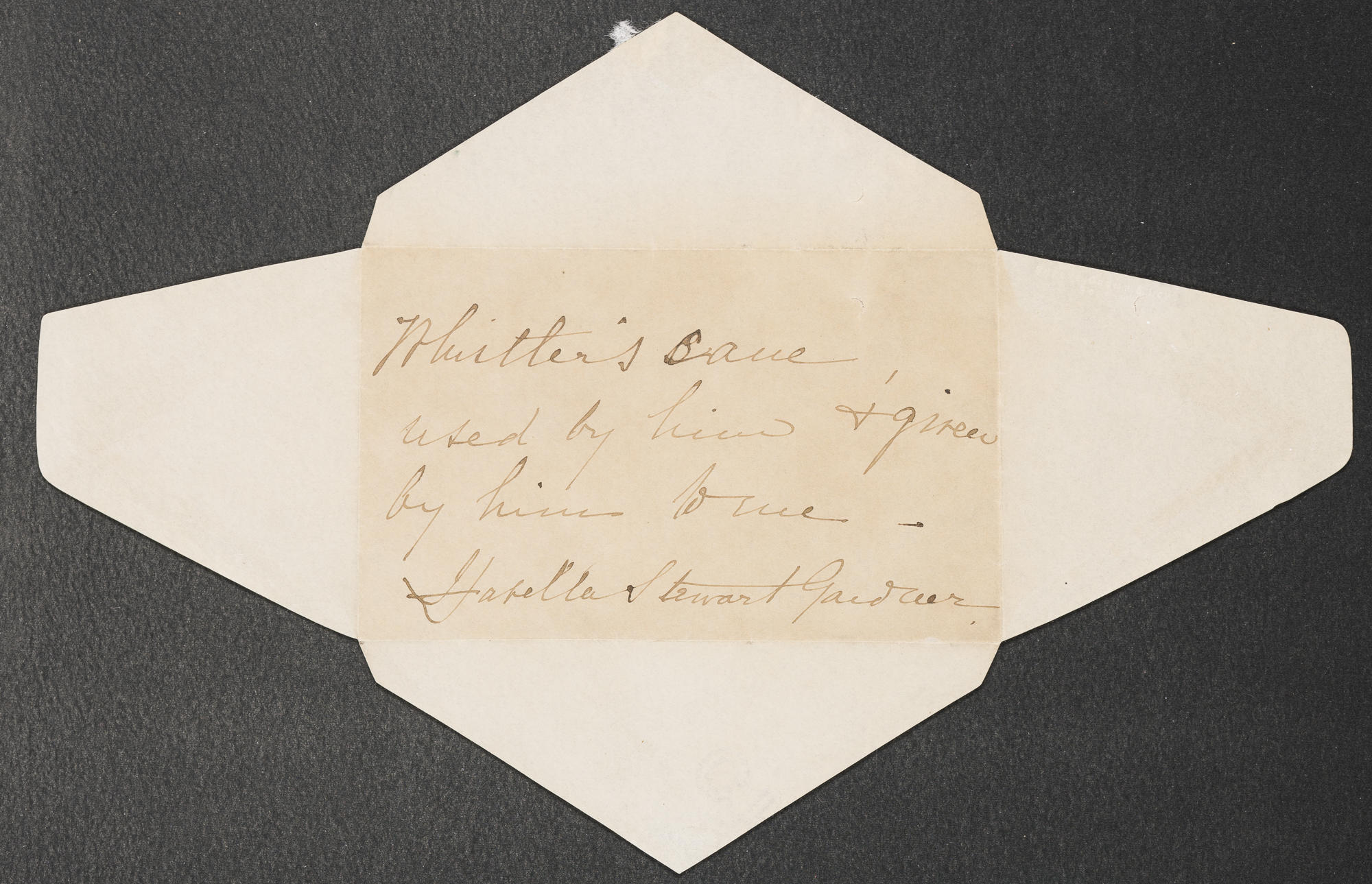

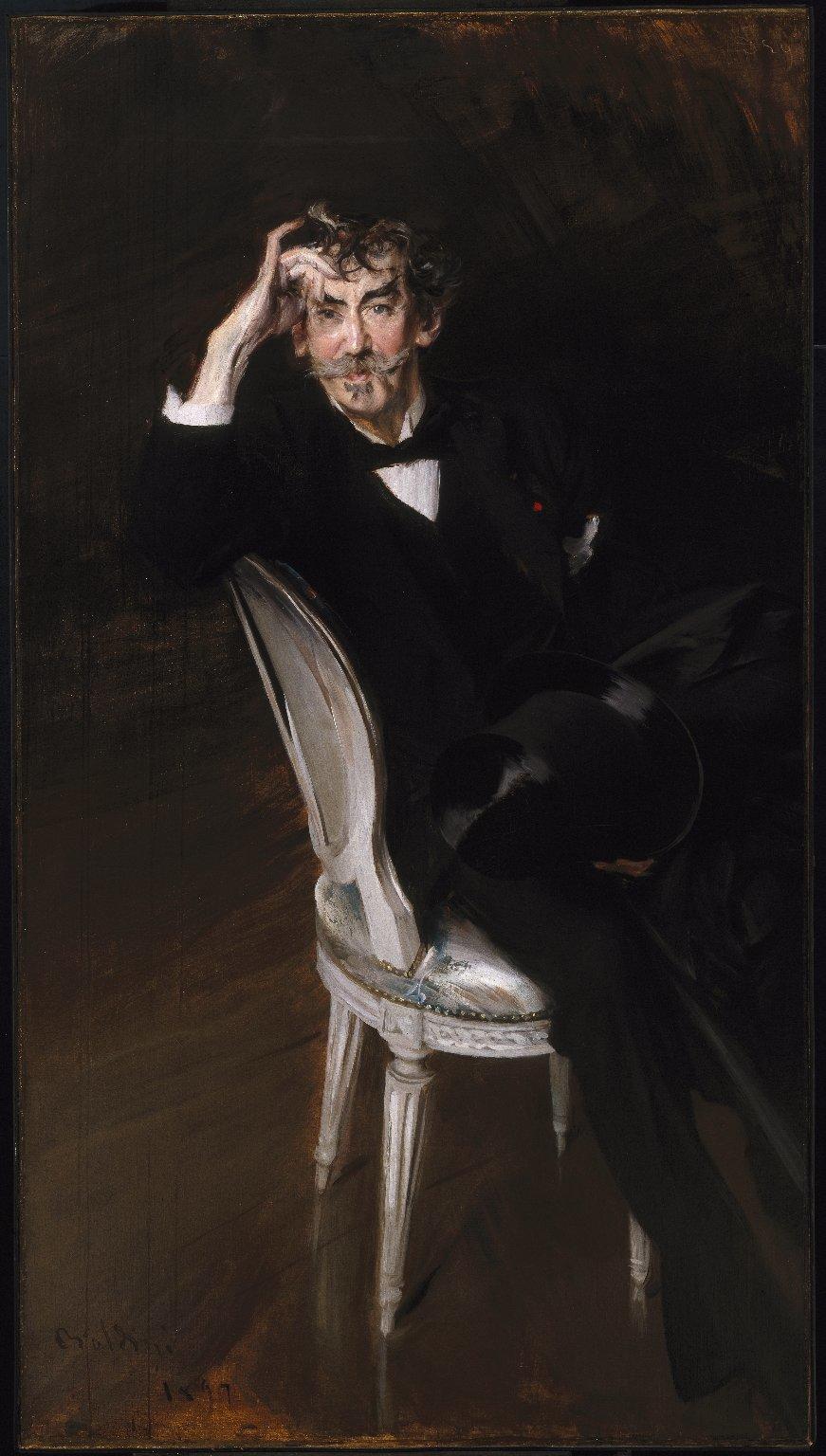

Although celebrated as an artistic maverick, one could not escape Whistler's penchant for stirring up drama. He often responded harshly to criticism or differences in artistic opinion, resulting in several broken friendships and widely publicized court cases. In 1877–78, he brought a libel suit against art historian and critic John Ruskin. Although Whistler won the case, he was awarded only token damages; as a response, he wrote a book describing his version of events, Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics. In 1890, Whistler was inspired to write another book, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies; the title speaks for itself. Whistler found himself in court again in the 1890s, defending his right to keep a portrait of a Baroness he was commissioned to paint. He had refused to hand it over because he thought the sitter demonstrated a condescending attitude towards him. He also wrote a book about that case: Eden versus Whistler: The Baronet & the Butterfly. Copies of all three books are in the Gardner Museum collection.

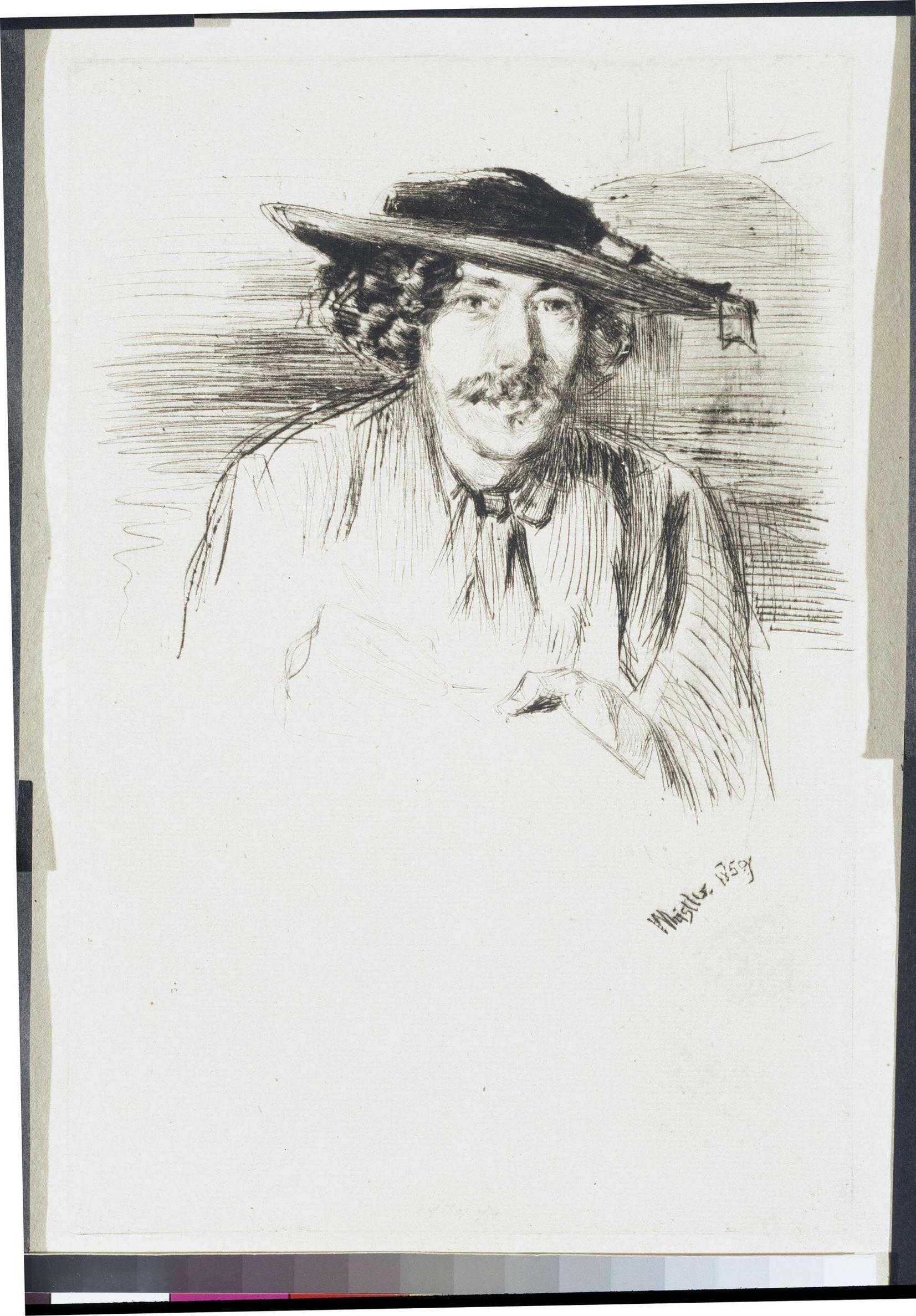

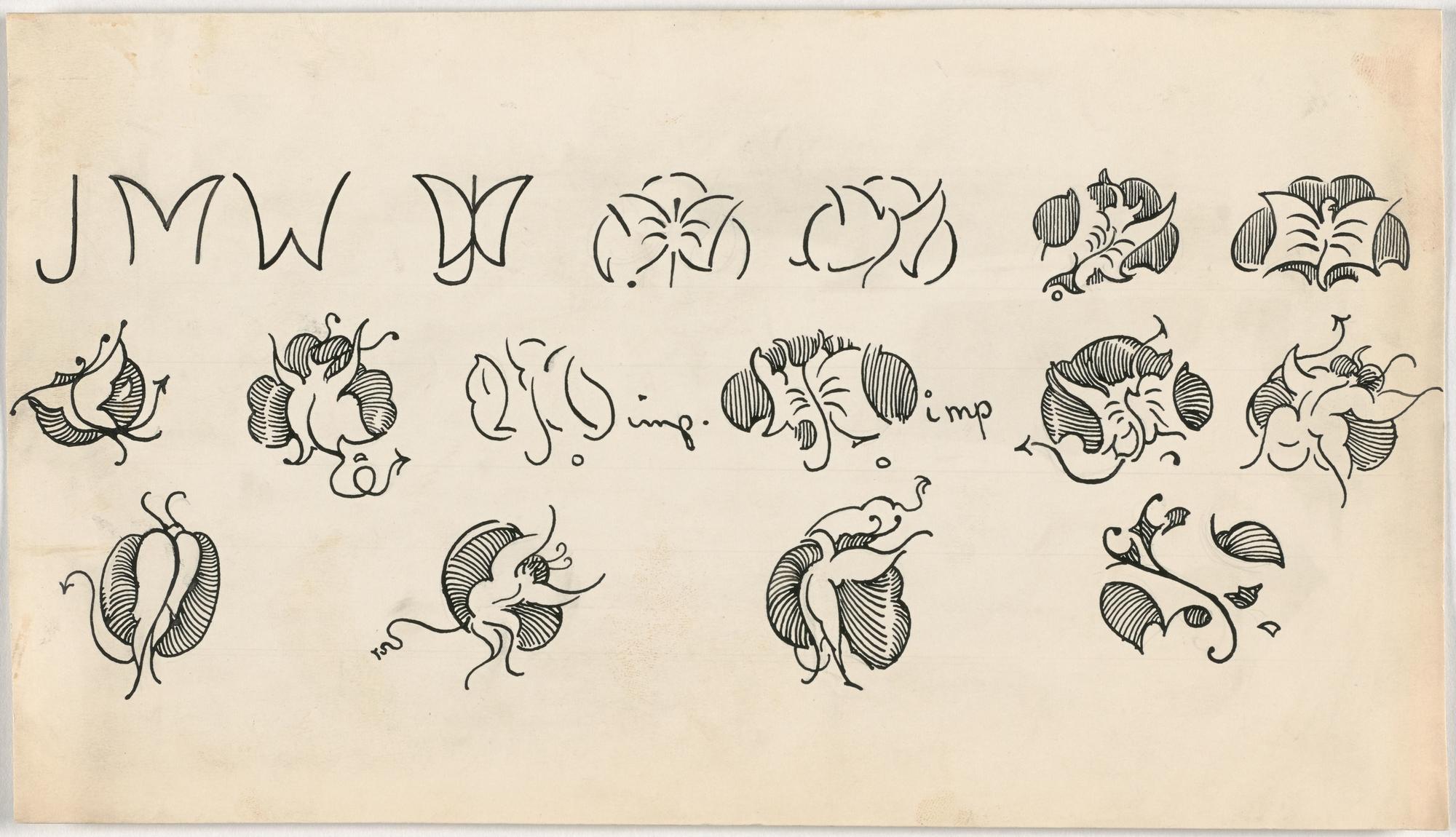

The "Butterfly" in this book's title refers to Whistler's bespoke signature created out of his initials (JMW): a stylized butterfly with a stinger tail. The imagery perfectly defines Whistler: expressing his delicate painting style (the butterfly) and his brash personality (the stinger).