Cafe G is closed for repairs from January 29 through February 16, 2026.

We apologize for the inconvenience.

Isabella Stewart Gardner’s induction into the Hispanic Society in 1911 reflected more than a fascination with Spain alone. Her enthusiasm for Spanish speaking cultures also found expression closer to home in the art of Mexico. In 1871, long before she began to collect the works of celebrated European painters, Isabella attended a sale of Mexican art in Boston.

Title page of the auction catalogue of Rare Original Paintings, Collected in 1861, from the Convents and Churches of Mexico….Leonard & Co. Auctioneers, Boston, 12 January 1871

The auction house offered “the noble pictures of Mexican masters” purchased from convents and monasteries dissolved by the Mexican government a decade earlier. In America, Mexico’s art was little known and the auctioneer reassured prospective buyers by citing its popularity at home: “Rich Mexican connoisseurs who have bought European works abroad, pay as high or higher prices for choice works of the native masters. For three centuries art flourished under the powerful stimulant of a rich church treasury and the fame of an admiring nation.”

For a mere thirteen dollars, Gardner bought a pendant pair of portraits attributed to the eighteenth-century Mestizo painter Miguel Cabrera (1695–1768) and installed them in her home at 152 Beacon Street. They now hang in the Museum’s Vatichino.

They depict Don Diego Caballero and his wife Doña Inés, a wealthy Spanish couple who owned the largest sugarcane plantation in New Spain and profited from the abundance of enslaved labor exploited by colonial settlers. In 1600, they founded a convent in Mexico City dedicated to Santa Inés. Intended for poor girls without dowries, it housed thirty-three nuns including the Caballeros’ nieces, as well as a number of orphans.

Gardner’s paintings of the convent’s founders are probably local copies after originals by Baltasar de Echave Orio (about 1558–about 1620).

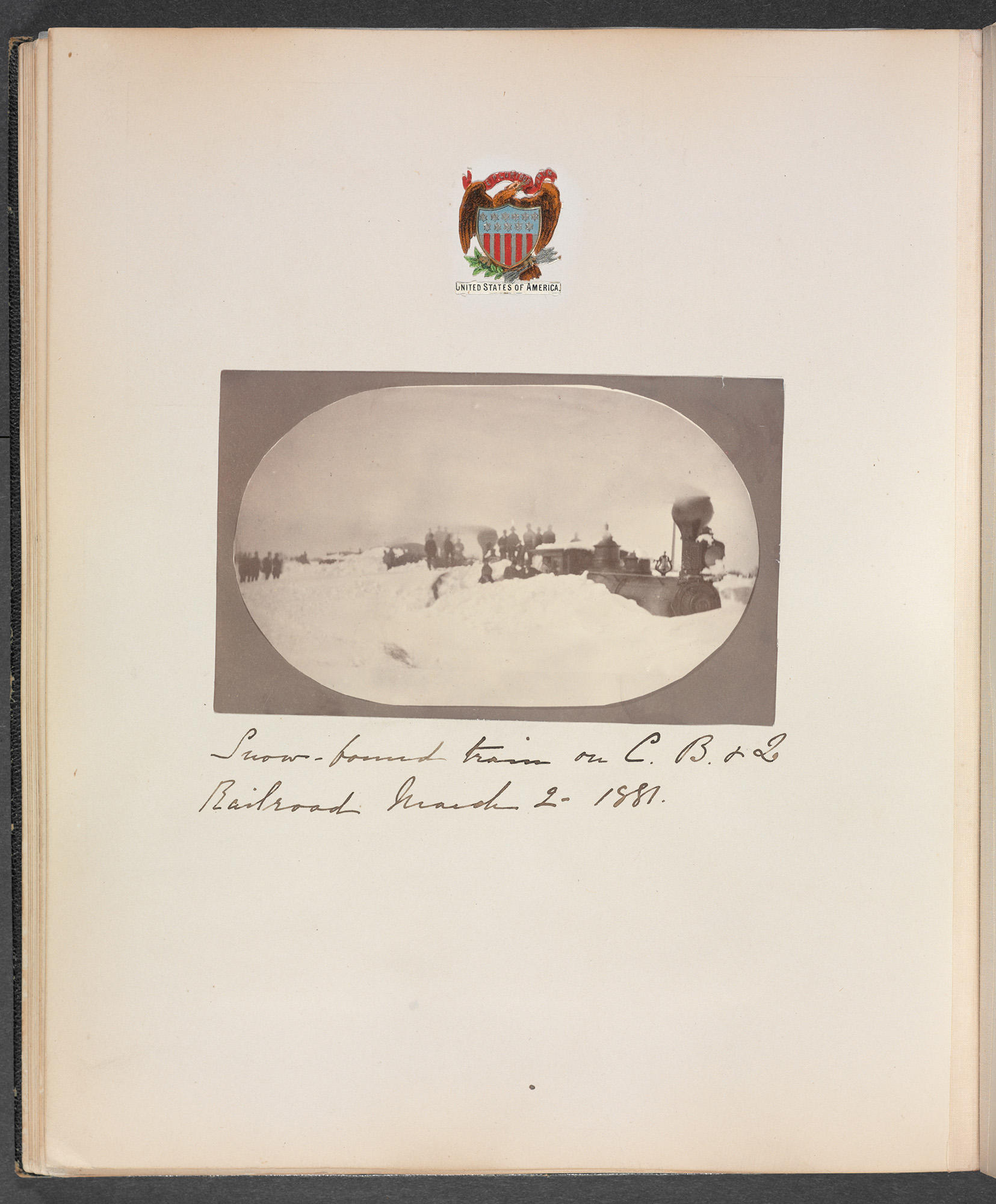

A decade after the auction Gardner made it to Mexico herself. In the spring of 1881, she and her husband joined a group of friends on a train journey across the American West. Isabella commemorated the trip in a travel album, including a map of their route made by her husband, Jack.

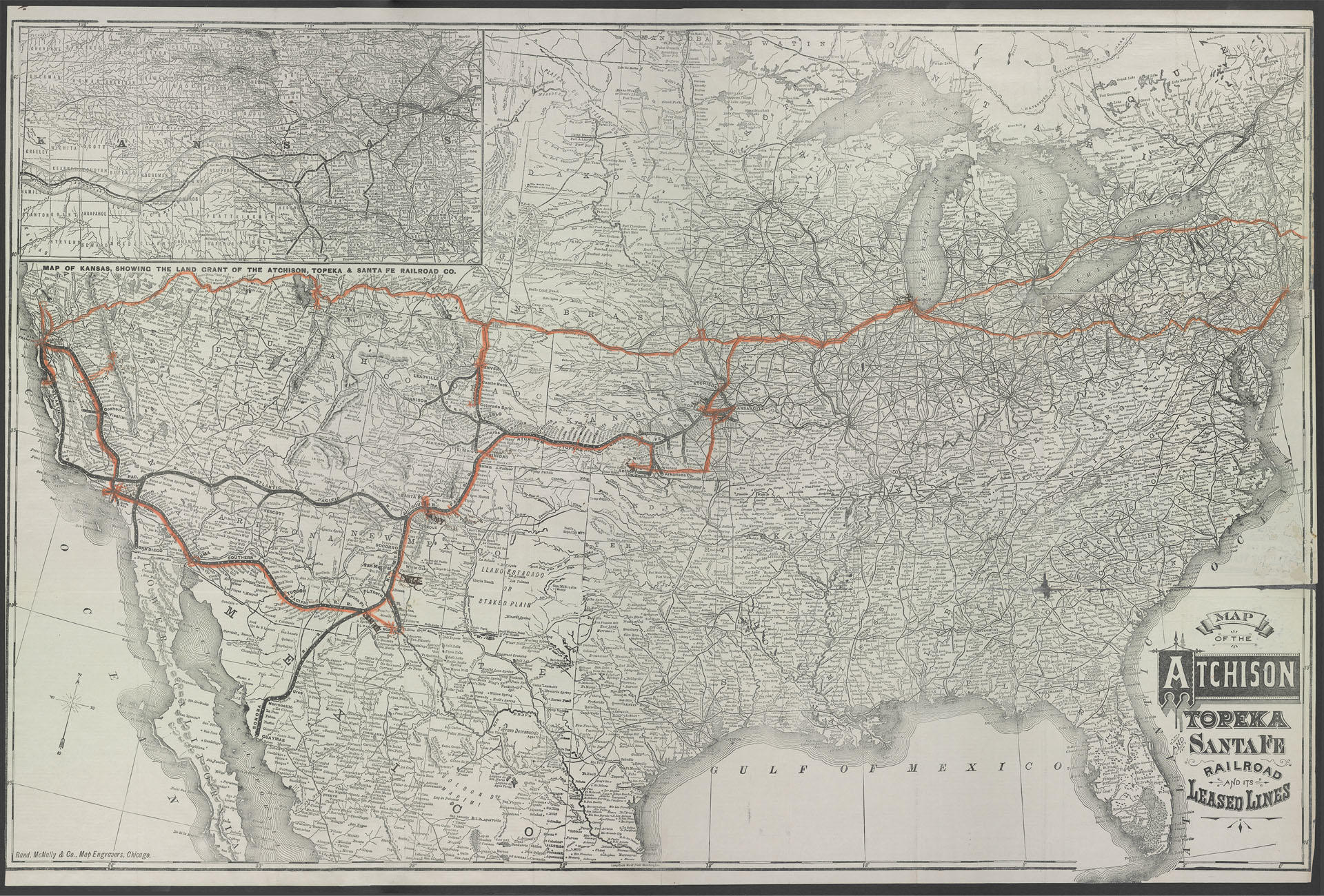

Rand McNally & Co., Map of the Atchison Topeka Santa Fe Railroad, about 1881, showing the Gardners’ route through the United States and Mexico, from Isabella’s travel album (v.1.a.4.1)

It began in snowy Chicago and continued south. On April 2 they left El Paso, Texas and drove into Mexico, fording the Rio Grande four times. No photographs survive, but Isabella recorded the brief excursion in her album and celebrated the event by pasting a souvenir into the book: a copy of the country’s emblem, a golden eagle perched on a prickly-pear cactus devouring a rattlesnake. Jack returned to Mexico several years later, but this remained Isabella’s only visit.

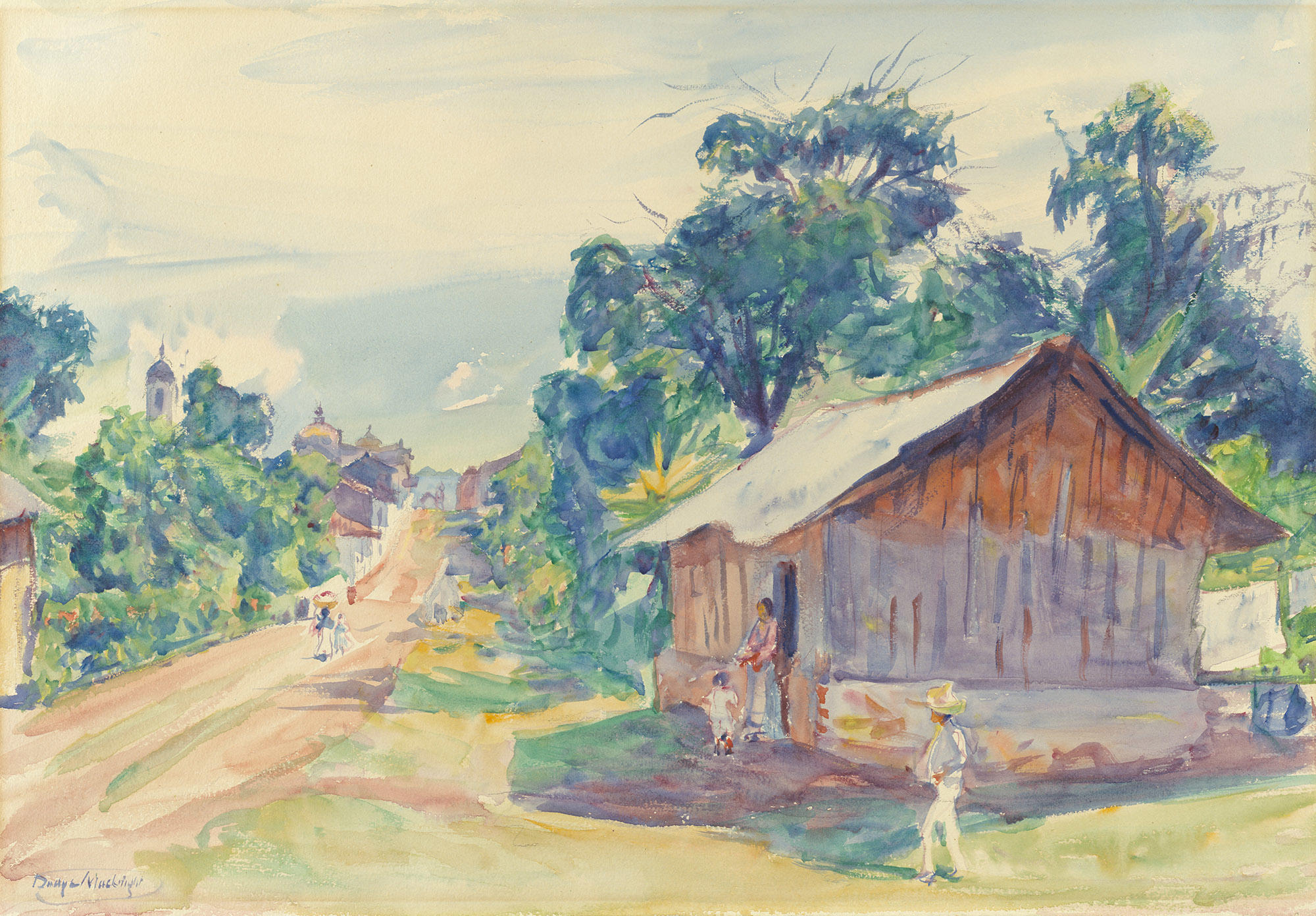

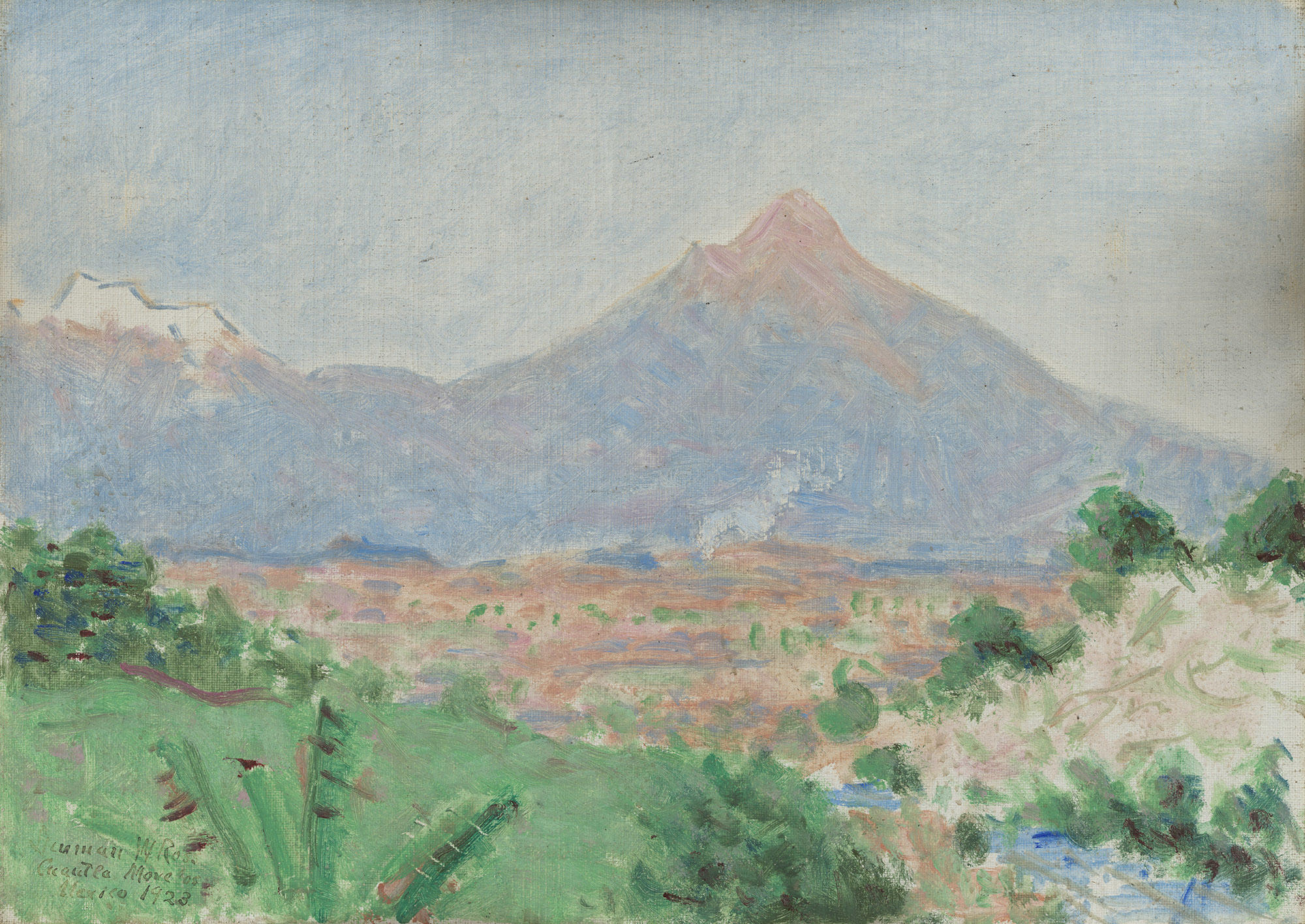

Several of Gardner’s friends and acquaintances decided to see Mexico for themselves, following in her footsteps. One invited Isabella to join him at the 1896 World’s Fair in Mexico City (not ultimately held), writing, “It would be an original experience… Come on, and let us see queer things.” But she had already been. Dodge Macknight, the philosopher Denman Waldo Ross, and photographer Carl Lumholtz all visited Mexico, one of whom may have given her the charming pen wiper in the shape of a sombrero in the Tapestry Room. Both Macknight and Ross recorded their journeys in paintings, two of which are preserved in the Museum.

Thanks to Dodge Macknight, Gardner was able to enshrine her fascination with Mexico at the very heart of the museum in the Spanish Cloister. Brightly painted Mexican tiles line its walls. Macknight purchased this group of 2,000 tiles directly from the church of San Agustín in Atlixco and sold them to Gardner.

Called talavera, the tin-glazed earthenware of the Puebla region was produced in the seventeenth century by local craftsmen who combined indigenous Mexican images with Spanish methods and motifs. They feature animals, floral motifs and figures from Indigenous and Christian histories.

Photo courtesy of Julie Featheringill

Tiles from the Church of San Agustin, Atlixco, Puebla, 17th century, in the Spanish Cloister

Not only did she cover the Spanish Cloister with Mexican tiles and install the portraits in the Vatichino but she originally hung in the Museum’s private stairway a set of sixteen mammoth plate photographs of the American West and Mexico by William Henry Jackson.* Gardner’s collecting of Mexican painting and pottery reveal another example of her cutting edge tastes. Long before an established market for it existed in America, she was already leading the way, pioneering a new field of collecting for others to follow. Gardner’s determination to make Mexico a part of her museum persisted throughout her life.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Read More on the Blog

Isabella and the Hispanic Society

Explore the Museum

Spanish Cloister

Read More on the Blog

A Tiny Sombrero

*donated by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum to the Boston Public Library in 1973