Learn More with the Recommended Reading

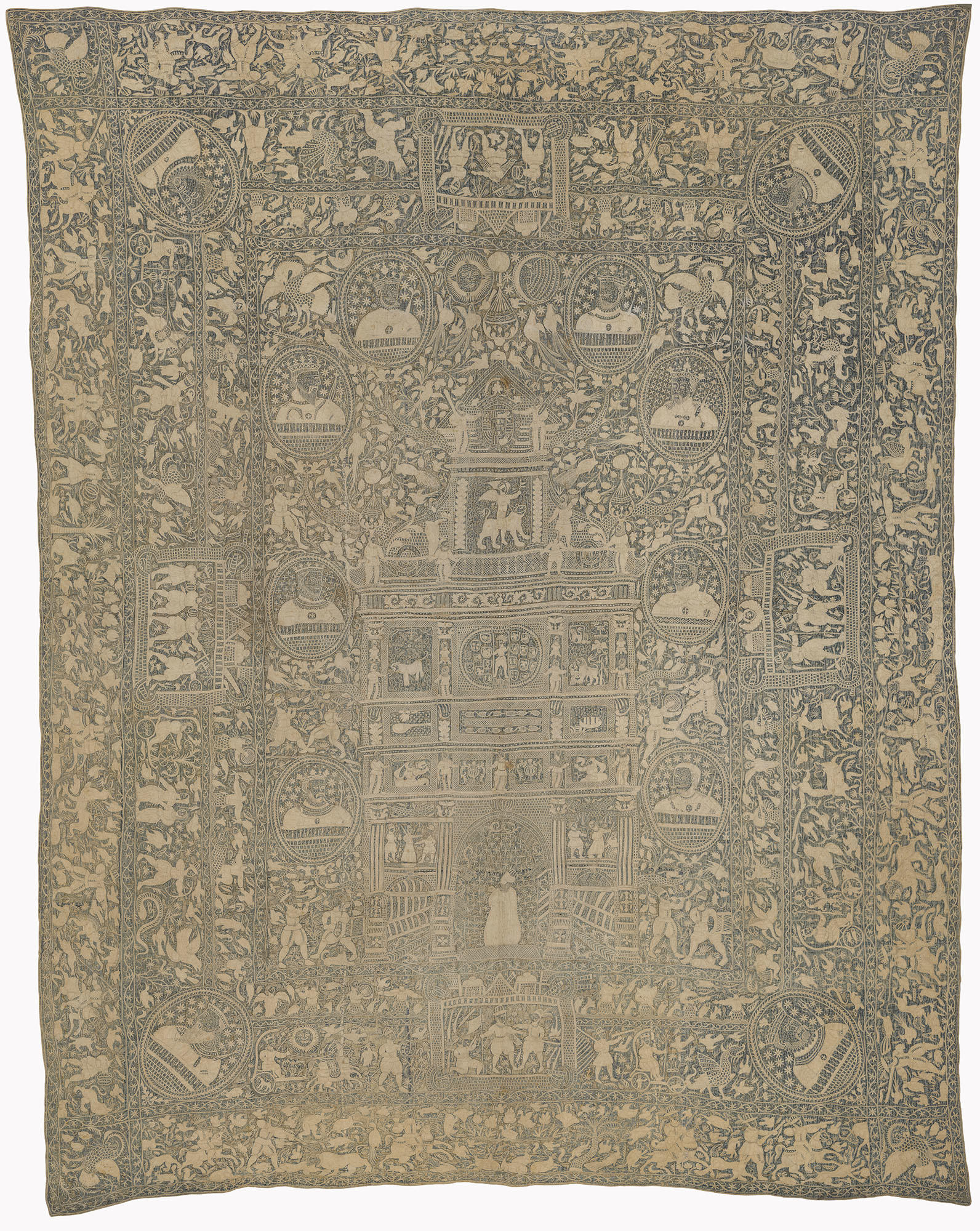

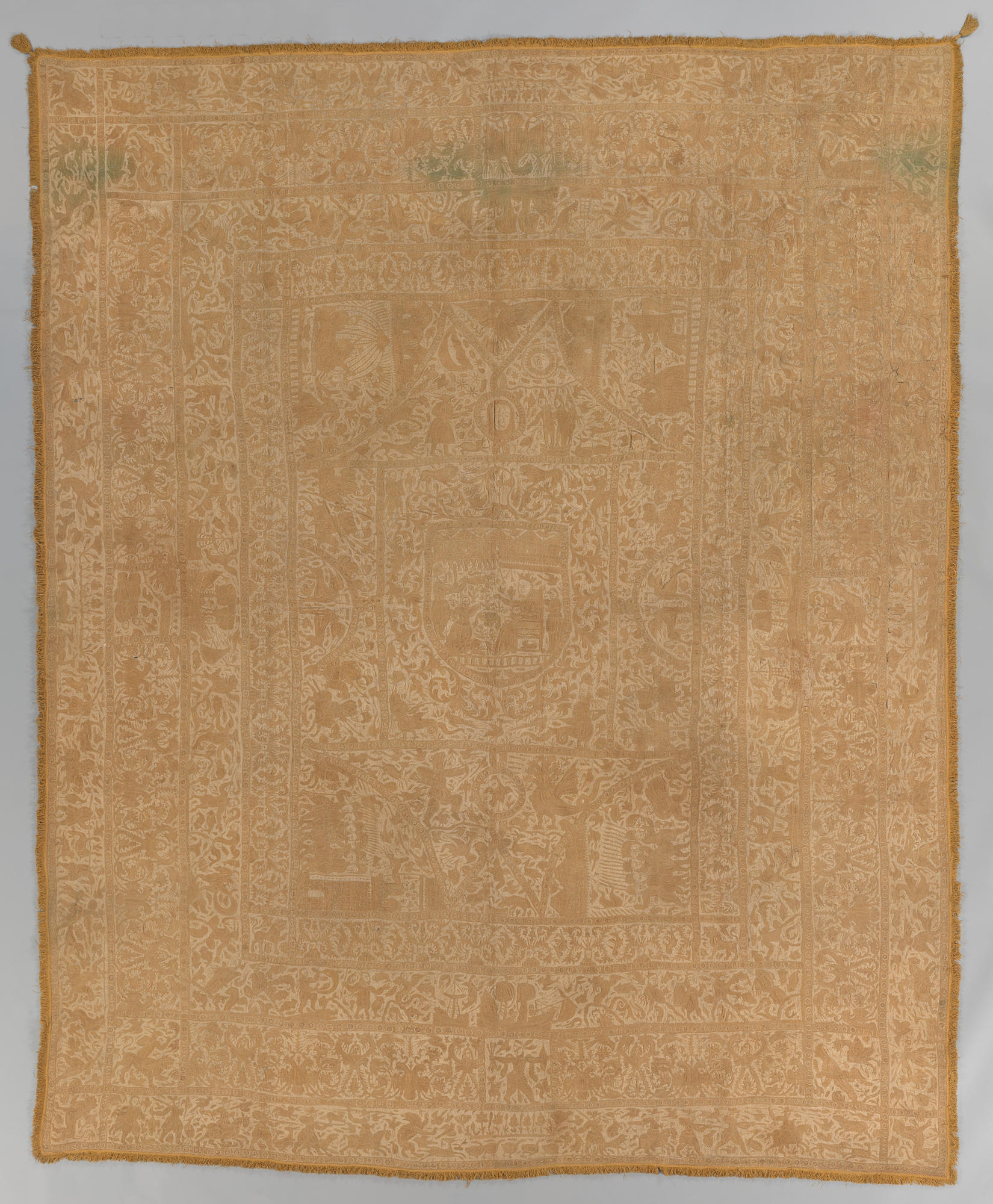

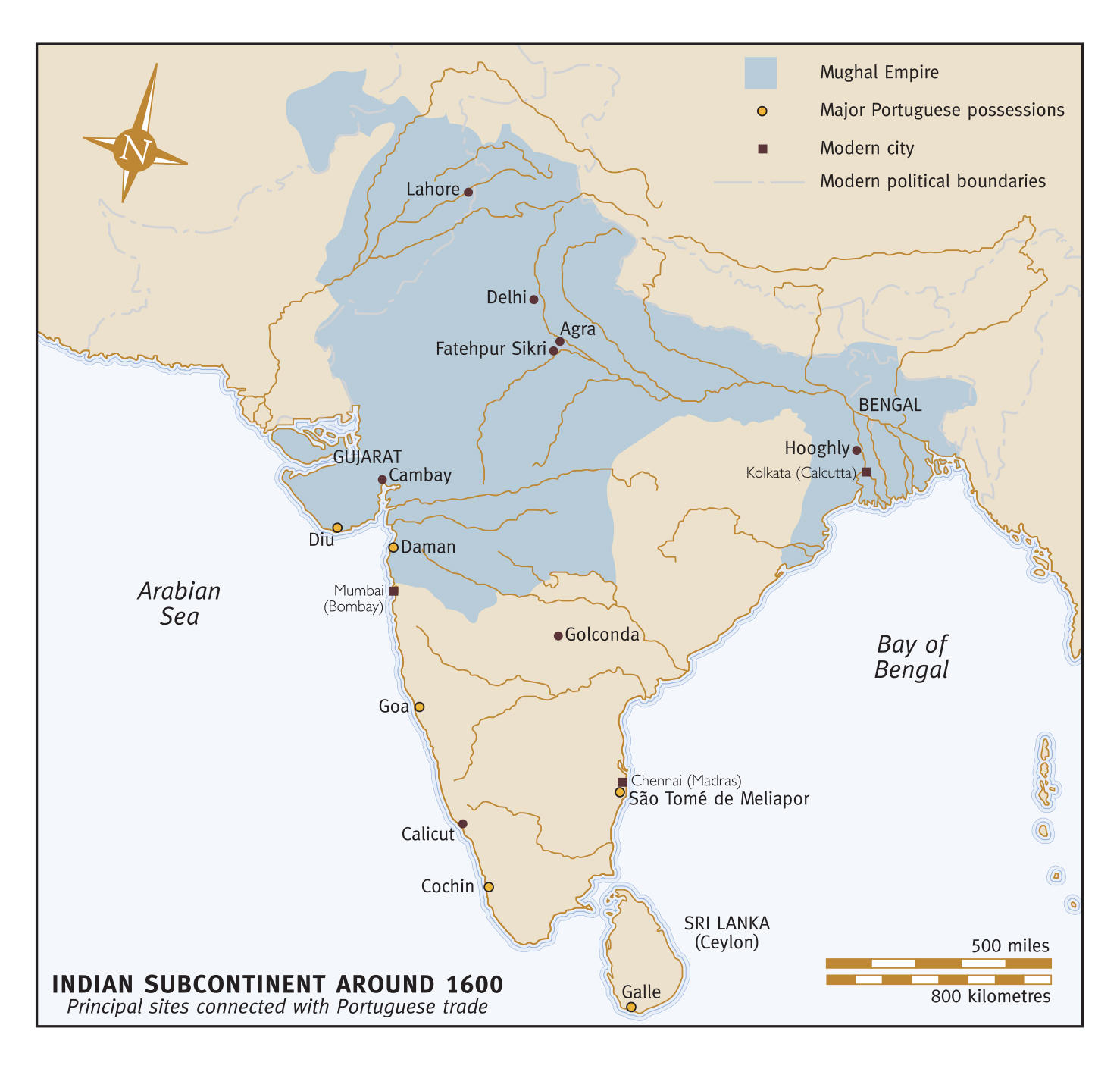

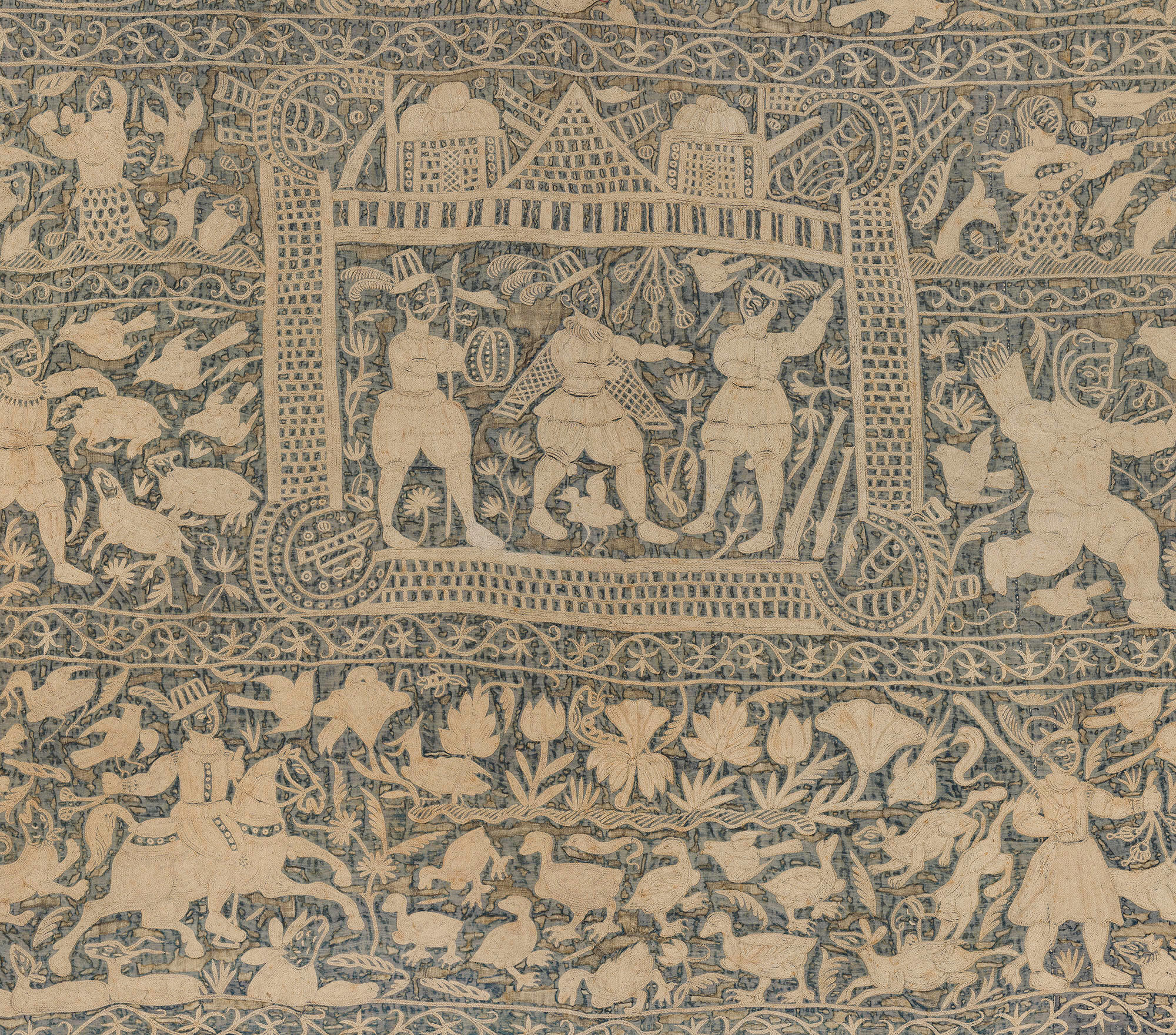

Pedro Moura Carvalho, Luxury for Export: Artistic Exchange between India and Portugal around 1600. Exh. cat. (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2008).

Especially the entries by Carvalho and conservator Tess Freddette on the Gardner colcha.

Pika Ghosh, Making Kantha, Making Home (University of Washington Press, 2020).

John Irwin and Margaret Hall, Indian Embroideries (Calico Museum of Textiles, India, 1983).

Barbara Karl, Embroidered Histories: Indian Textiles for the Portuguese Market during the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Gmbh & Co, 2016).

Darielle Mason, ed. Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection and the Stella Kramrisch Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Yale University Press, 2010).