In 1897, shortly after purchasing Titian’s Rape of Europa, Isabella Stewart Gardner wrote to her friend, the art historian Bernard Berenson, “The electrician has come to arrange for Europa’s adorers, when the sun doesn’t shine. You have no idea how difficult it is to arrange light satisfactorily.”*

The Drawing Room at Isabella Stewart Gardner’s home on Beacon Street in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood, 1900, showing Titian’s Rape of Europa

Photo: Thomas E. Marr & Son (active Boston, about 1875–1954)

By the time she opened the Museum six years later, Gardner had given up on attempts to use electricity and chose instead to deliberately install many of her works next to windows to capitalize on the ample, natural light. As she had located Fenway Court in an undeveloped neighborhood, she also ensured that no building would cast her museum in its shadow.

For instance, she ultimately installed Fra Angelico’s radiant Dormition and Assumption of the Virgin next to a window in what is now the Early Italian Room, even if it meant distancing the painting from the gallery’s entrance. The effect of sunlight dancing off of the gold and bright colors was more important to Gardner than placing this valuable piece in a prominent location.

Early Italian Room showing Fra Angelico’s Dormition and Assumption of the Virgin

At night, Isabella combined lighting technologies of the past and present. Electric lighting illuminated her apartment on the top floor of the Museum, but she relied on candles and fires to dazzle visitors in her galleries—much to the enjoyment of some and frustration of others, who wrote to her about having trouble seeing paintings under these conditions.

Tapestry Room showing a French Fireplace, 1338–1365

Photo: Sean Dungan

Despite the obvious need for light in the galleries, too much light can also be dangerous for individual artworks. Light can cause fading, discoloration, and other permanent damage. Bright light over a short period of time may cause as much harm as a low light over a long period of time. And the use of fire and candlelight is simply not safe—even Gardner understood the harmful effects of light, and would only open her galleries for limited amounts of time. When closed, she had the Museum’s windows shaded. In the summer, the glass Courtyard roof was painted over to prevent unnecessary exposure.

Fabric from the walls of the Raphael Room showing light damage

In 1925, the year after Gardner’s death, the Museum introduced regular public hours. Staff hung curtains in the windows to reduce light and heat when the galleries were open. Electric lighting was the next logical evolution, beginning with the electrification of candle fixtures. Then as now, the Museum works to achieve a balance between conservation requirements and visitor experience.

Gardner’s personal installations pose an additional challenge to providing adequate lighting. For instance, she installed light-sensitive works, like watercolors and textiles, next to less sensitive paintings and sculpture. Uniquely, her will requires that the arrangement of art in her museum remain unchanged, “for the education and enjoyment of the public forever.”† Thus, we are often obliged to keep the overall light levels at a minimum in order to preserve all of Gardner’s carefully chosen works of art.

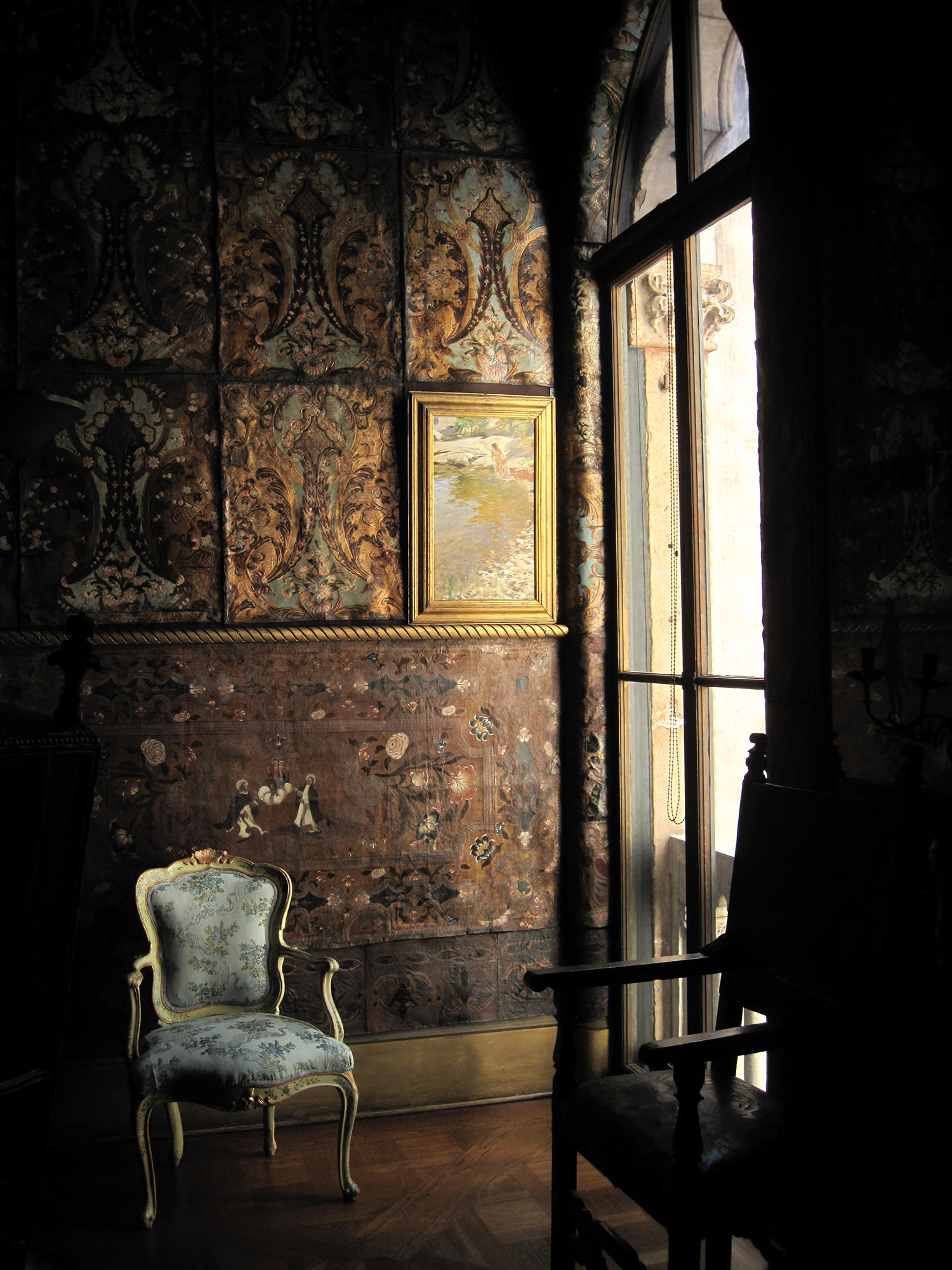

Veronese Room showing Anders Zorn Morning Toilet and leather wall coverings

Photo: Joseph Saravo

Thanks to modern technologies, the quality of light will continue to improve throughout the Museum. Upgrading and improving lighting fixtures and arrangements is a current project, and we continue to undertake a range of conservation campaigns, from the cleaning of individual works of art to the refurbishment of entire galleries. We hope that you visit the Museum in the near future to see these galleries in a whole new light.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Learn More

Creating the Titian Room

Learn More

Conservation at the Gardner

Learn More

Turning Back the Clock: The Raphael Room Textiles

*Isabella Stewart Gardner, Letter to Bernard Berenson, 1 January 1897. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

†Will and Codicil of Isabella Stewart Gardner, 9 May 1921, probated 23 July 1924, Suffolk County, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Clara L. Power, Assistant Register.