On a frosty January evening in 1903, Isabella welcomed the public into her museum for the first time. The artwork was illuminated by the soft glow of thousands of candles and the Courtyard bloomed with flowers in the middle of Boston winter. Isabella held court during this lavish affair and, as the legend goes, served her guests champagne and doughnuts.

As these inaugural visitors celebrated and imbibed in the new and unexpected space, the god of wine and his followers were also present at this first celebration. Tucked between two dolphins above the Courtyard fountain, a solitary dancing maenad had the best seat in the house to witness the festivities.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.011020)

Thomas E. Marr and Son (active Boston, 1910–1942), Courtyard, Fenway Court, Boston, 1902. Gelatin silver print

Maenads, Dionysus, and Bacchanalia

Maenads were the female followers of the Greek god of wine, Dionysus, or his Roman equivalent, Bacchus. In reverence to their god, maenads were known for entering into an altered state of consciousness, known as ecstatic frenzy, through dance and intoxication.

The Gardner’s own life-sized maenad was discovered along an ancient Roman road, Via Praenestina. She belonged to a series of eight maenad reliefs that once decorated the circular base of an unknown monument dedicated to Dionysus. Today, her seven companions are held at Museo Nazionale Romano, forever frozen in eternal ecstasy.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S5s19)

Roman, Dancing Maenad Relief, 50 BCE. Marble, 143.5 x 58.4 cm (56 1/2 x 23 in.)

Cults and celebrations involving this type of worship developed in both ancient Greece and Rome. People of all genders, ages, and classes were drawn to the freedom of the uninhibited veneration of the wine god, culminating in the Roman Bacchanalia. These privately funded festivals came under scrutiny by the Roman Senate, who tried to reform the celebrations in order to assert civil and moral control. However, even under the thumb of the Republic, the festivities persisted.

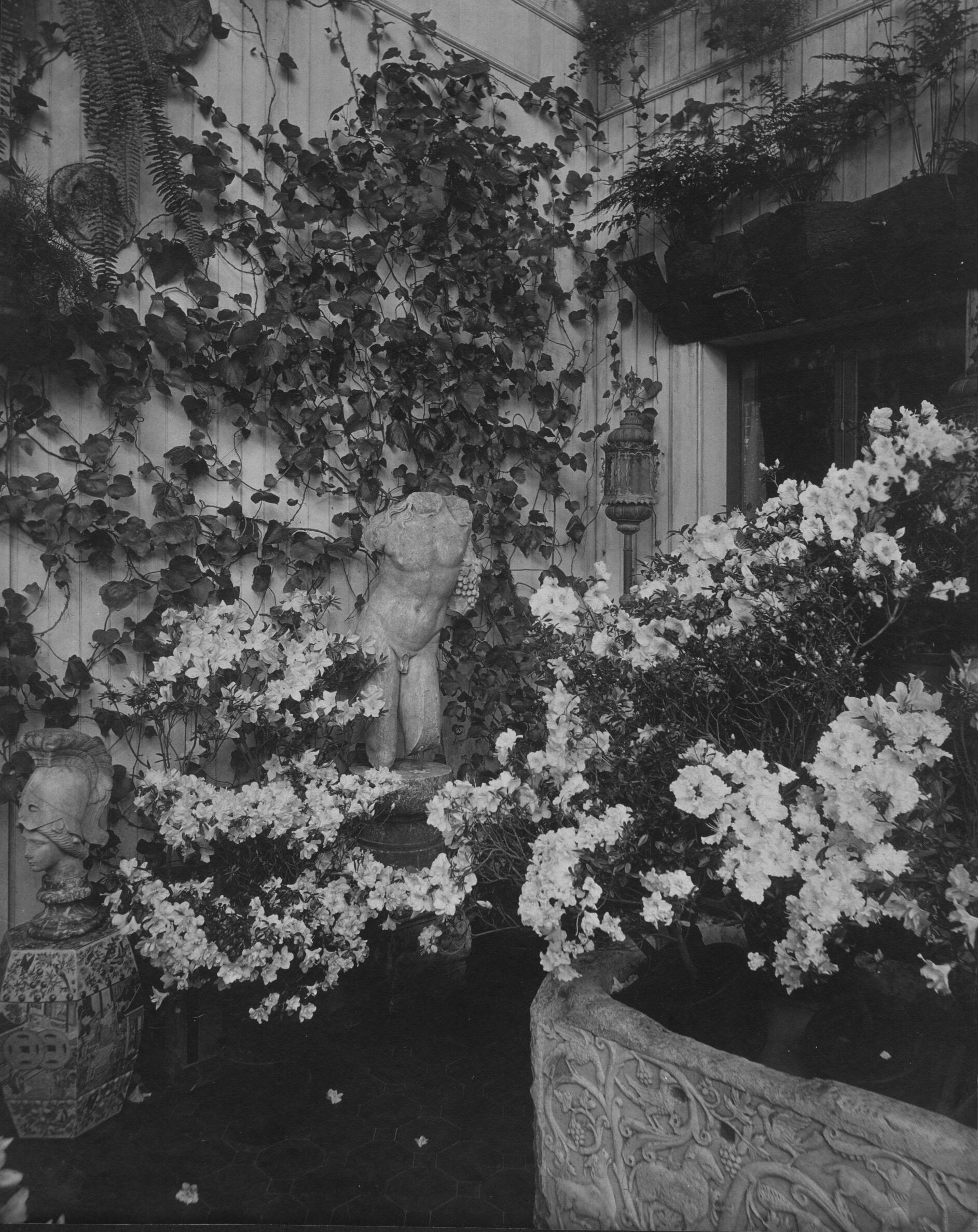

Isabella & The Wine God

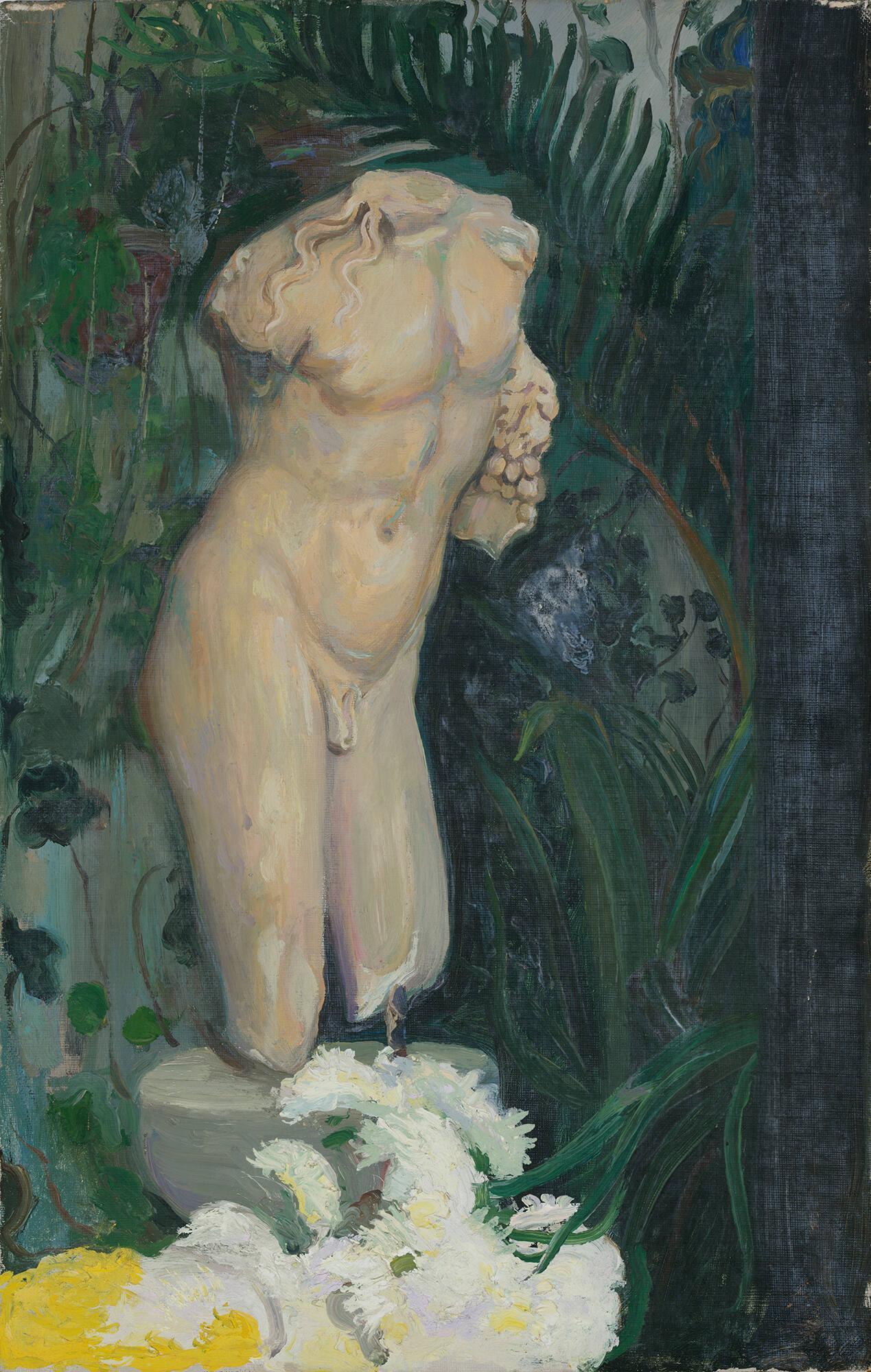

The first of Isabella’s incarnations of the wine god, a Torso of Dionysus, appears in the Conservatory of Green Hill, her Brookline residence, in 1900, set against a backdrop of lush vegetation. He entered Isabella’s collection as the “Borghese Bacchus,” suggesting he came from the collection of the Borgheses, an Italian noble family from Rome who were prolific art collectors and patrons. However, this provenance is unconfirmed.

When the torso was moved to the Museum, Isabella displayed him in three different gallery spaces before moving him to his permanent perch along the windows in the Chinese Loggia.

With grapes tucked neatly under one arm, the youthful god is sensually sculpted. Long, flowing hair drapes over both shoulders, and his lithe torso is both soft and defined. In 1902, young artist Andreas Martin Andersen was invited to the Museum, where he painted the sculpture with a broad palette of colors, further defining the subtleties of its form.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P33w12)

Andreas Martin Andersen (Norwegian, 1869–1902), Dionysus Torso at Fenway Court, 1902. Marble, 128.3 x 38.7 x 34.9 cm (50 1/2 x 15 1/4 x 13 3/4 in.)

Revelers Gathering Grapes

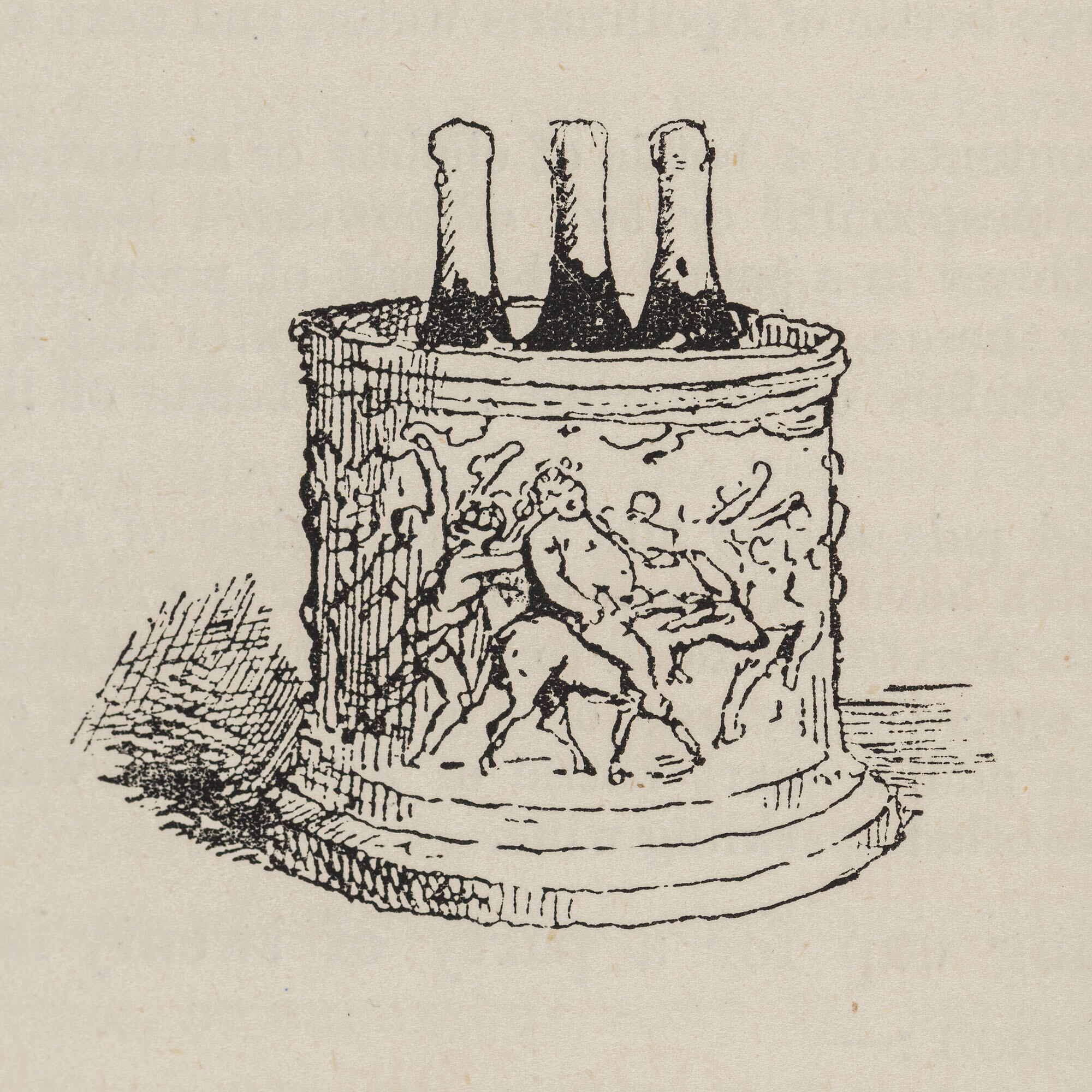

In the northern end of the West Cloister, the Farnese Sarcophagus commands the space with a masterful, high relief narrative of grape-harvesting maenads and the famously mischievous, and nude, companions of Dionysus—satyrs.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S12e3)

Roman, Farnese Sarcophagus with Revelers Gathering Grapes, about 225. Marble, 163.2 x 62.2 x 26.7 cm (64 1/4 x 24 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.)

Satyrs were the male counterparts to maenads in the mythical retinue of Dionysus. They were minor deities commonly depicted as intoxicated and extremely lustful, with animal-like features, such as horse ears or tails. The satyrs on this Roman sarcophagus are relatively tame and less provocative compared to earlier Greek depictions. Their youthful, human-like appearances paired with the graceful, grape-harvesting maenads creates a pastoral, yet teasing, narrative.

It was common to find these Dionysiac motifs on Roman sarcophagi, as the harvest of grapes and making of wine was seen as symbolic for the cycle of life. They also served as a reminder to embrace each day and live life to the fullest.

Silenus

A final, important member of the thiasos, or ecstatic entourage of Dionysus, was an old satyr named Silenus—the wise, wine-loving tutor and companion to the god. Silenus is considered older than the rest of the satyrs in the retinue. He is often depicted as bearded and bald, carrying fruit, a goblet, or a wineskin. Since his wisdom is often linked to his extreme inebriation, it is common to find him being carried by satyrs or on the back of a donkey.

Silenus has a strong presence in the Gardner’s collection, with figures easily identified by his commonly associated symbols. On opposite corners of the Farnese sarcophagus, there are examples of a bearded Silenus holding a basket of fruit on his head, perhaps in anticipation of a feast to celebrate the harvest. One floor above in the Raphael Room, a small statuette of Silenus greets visitors on the center table as soon as they walk in. He carries a wineskin over his shoulder, leaning with its weight.

Worship of Dionysus and Bacchus endured through antiquity, but declined during the Middle Ages. However, the god himself never disappeared entirely. Renaissance and Mannerist artists continued to find inspiration in his form and legend—an inspiration that persisted through to the modern era.

On this day, National Wine & Cheese Day, may we also be inspired by Dionysus' legacy and live life to the fullest. Cheers!

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Secrets of the Farnese Sarcophagus

Gift At The Gardner

Medusa Face Wine Stopper

Treat Yourself

Café G