Anyone entering the rooms of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is at once struck by the opportunity of discovery. The shadowy rooms are full of enticing paintings, furniture, and ancient works of art. By contrast, the views out of the Venetian Gothic style windows are of a courtyard filled with flowers and sunlight, reflected off the pink and white stucco walls.

When I visited in April 2025, these walls were partly smothered by the fresh green trailing tendrils and brilliant oranges of nasturtiums, harbingers of spring on a cold winter day. On turning back inside to the rooms, it takes a while to focus. The lighting is subdued, mostly given out by elaborate chandeliers, wall brackets, and standing candlesticks, all made of wrought iron, a number tactfully fitted with electric lamps. The atmosphere evoked is that of a 19th century collection, rather than a modern museum—exactly the ambience Isabella Stewart Gardner aspired to.

Consulting Curators, Jane Geddes, Professor Emerita, University of Aberdeen and Marian Campbell, former Senior Curator of Metalwork, Victoria and Albert Museum at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston in the Spring of 2025

Earlier in the 19th century, one of the wealthiest French art collectors and archaeologists, was Alexandre Du Sommerard (1779–1842). His large apartment was in the medieval palace known as the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris. There he lived surrounded by his vast art collection of medieval and Renaissance artifacts. At the time of his death, he had gathered together more than 1,500 objects, which now form the Musée de Cluny. A painting of a crowded room in the Du Sommerard collection captures the shadowy atmosphere of a 19th-century intellectual's ideal interior space, filled with rich textiles, Gothic furniture, and historic objects.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris (Inv. No. 15814). Photo: Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Louis-Vincent Forquet (French, 1803–1869), Cabinet de M. Sommerard, 1836. Oil on canvas, 81 x 100 cm. (31 ⅞ x 39 ⅜ in.)

The rooms of the Gardner Museum have intentionally low light levels to preserve the collection, although they also echo the atmosphere of the past. From remote antiquity until the nineteenth century, the principal source of night-time lighting in most houses was from the fire. However, the largest and grandest houses and churches used a wealth of lamps, rushlights, and candlesticks. Most of these were set into holders made of wrought iron, hammered into shape by a blacksmith.

Working with Iron

Iron was ideal for the purpose, as it is sturdy yet heat resistant. The very core of the earth is made up of molten iron, accounting for around 35% of earth’s weight. Iron is a material of paradoxes: strong and hard when cold yet soft and malleable when red hot. Glowing red, or white hot, it has a plasticity that is in amazing contrast to its extreme rigidity when cold. When polished it becomes a lustrous grey. Otherwise it can be painted or gilded. As long ago as 2800 BCE, humans had mastered the technique of heating the iron ore with charcoal at a temperature of about 2200 degrees Fahrenheit (1200 degrees Celcius). At this heat, a blacksmith can work the iron on an anvil quickly to shape the metal during the brief time that it remains malleable.

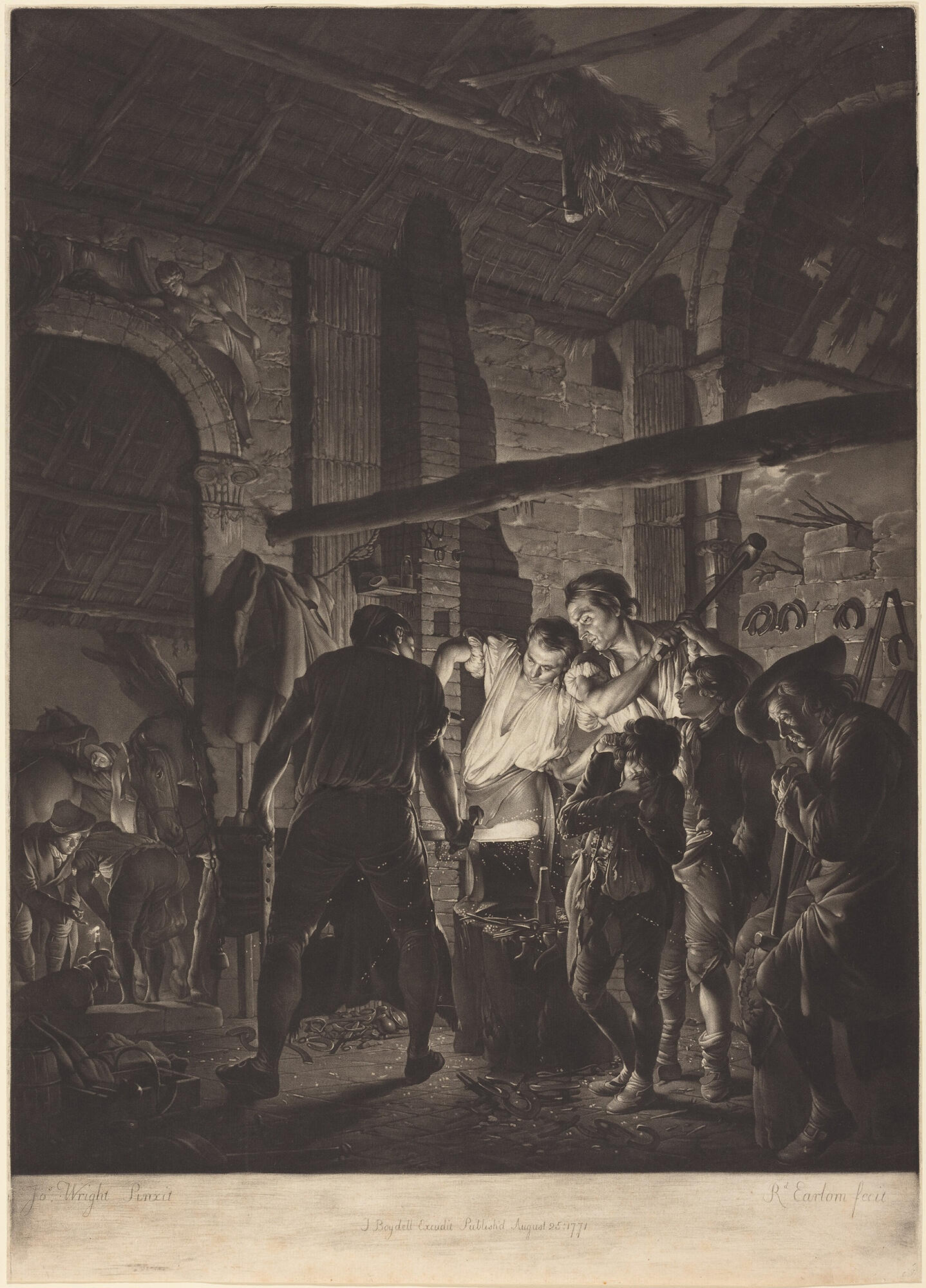

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Paul Mellon Fund (2001.96.6)

Richard Earlom (British, 1743–1822), after Joseph Wright (British, 1734–1797), The Blacksmith's Shop, 1771. Mezzotint, State i/ii, 61 x 43.9 cm (24 x 17 5/16 in.)

Lighting by Oil

Oil lamps were one of the oldest forms of lighting. At their simplest all that was needed was a floating wick and a container for the oil, usually extracted from fish livers. Early examples of containers often consisted of a plain iron dish with a spout at the front for the wick, and another dish beneath to catch the drips. Called crusies in Britain, they are better known as Betty or Phoebe lamps in North America. Very widely used until the nineteenth century, their design probably goes back at least to the middle ages. Being undecorated and of fairly uniform shape, they are timeless and impossible to date. The Gardner Museum has a fine example of a double crusie lamp in the Tapestry Room.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (M19s16). See it in the Tapestry Room.

American or Northern European, Double Crusies, 17th century–19th century. Wrought iron, 9.1 x 15.2 x 8.9 cm (7 1/2 x 6 x 3 1/2 in.)

Lighting by Candle

Medieval candlesticks consisted of spikes or prickets on which candles were impaled, but by the 15th century these prickets were superseded by the socket-type of holder. Standing candlesticks—sometimes very ornate and with many candle-holders—allowed light to fall over a much wider area, and were probably used in large houses and churches starting in the middle ages. A tall pair of Italian torchères decorated with leaves, grapes, and birds can be seen in the Long Gallery.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (M27w60.1-2). See them in the Long Gallery

Northern Italian, Pair of Torchères, 19th century. Wrought iron, height: 183 cm (72 1/16 in.)

In contrast to its Italian cousin, the distinctive style of the Spanish standing candlestick in the Gothic Room combines elaborate Gothic-revival tracery, a delicate branching pattern, with elements of embossed work known as ‘plateresco’. The tracery panels have extra fastening holes, indicating they may have been taken from another object and reassembled in the 19th century. The wear on the bottom suggests it may have been outside at some point.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (M30s35). See it in the Gothic Room.

Spanish, Torchère, 19th century (with 15th century elements). Iron, height: 146.7 cm (57 3/4 in.)

Candles supported in wall-brackets, known as sconces, were also in use from the middle ages until the 19th century. Churches, cathedrals, and great halls—like the Long Gallery at the Gardner—needed the greater illumination provided by chandeliers, suspended from the ceiling, some able to hold two dozen or more candles.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (M27c2). See it in the Long Gallery.

Unknown, Chandelier, 19th century. Cast bronze or brass and wrought iron

The Premier Lighting Specialist: Edward F. Caldwell & Co.

Decorative ironwork is notoriously hard to date, since it can feature many styles and often shows little wear. Many of Isabella’s purchases date to the 19th century, their design sometimes historicist versions of medieval or 18th century styles. There are rather few records about which dealers were providing her with lighting. It seems likely that she acquired more than is recorded from an American manufacturer, the great lighting specialist of the era, the firm of Edward F. Caldwell & Co.

Smithsonian Libraries, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The Pine Showroom at Edward F. Caldwell & Co., 38 West 15th Street, New York, 1920s

Edward F. Caldwell & Co. of New York City, was the premier U.S. designer and manufacturer of electric light fixtures and decorative metalwork from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. Founded in 1895 by Edward F. Caldwell (1851–1914) and Victor F. von Lossberg (1853–1942), the firm’s production of highly decorative work focussed on custom-made lanterns, chandeliers, ceiling and wall fixtures, many designed for electricity, then a novelty. Their commissions for major public buildings included work for the Boston Public Library. The objects made by Caldwell & Co. took the form of a wide variety of historic styles, since many of their wealthy and established clientele preferred traditional designs. Isabella must have been one of many; Caldwell designs can be found throughout the Museum.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (M21s9.1-6). See the set of six in the Dutch Room.

Edward F. Caldwell & Co. (active New York, 1895-1959), Sconce, about 1900. Gilded iron

Next time you visit the Gardner Museum, take a moment to notice the fixtures made of iron. In the words of the influential medieval writer, Bartholomaeus Anglicus, and author of the most popular encyclopedia of his day, De proprietatibus rerum (“On the Properties of Things”):

Iron is more useful to man than gold.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Shedding Light on the History of Lighting

Read More on the Blog

Fire-breathing Dragons on the Decorative Ironwork

Read More on the Blog

Imperial Crane and Turtle Box