Isabella Stewart Gardner supported many women artists, authors, and designers. However, only a handful of pictures in the Museum are painted by women. Isabella displayed one of them—The River at Concord by Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts— in the Macknight Room.

In 1915, shortly after the purchase of The River at Concord from Doll and Richards, an art gallery in Boston, Roberts wrote Isabella a thank-you note. Gardner saved her letter and displayed it in a place of honor in the Modern Painters and Sculptors Case in the Long Gallery alongside the correspondence of Cecilia Beaux, John La Farge, and Anders Zorn.

Mr. Turner of Doll & Richards tells me that "the blue § gold landscape" has been sent to you, and I would like to have you know how much pleasure it gives me to feel that you cared enough about the pictures to buy one — It is most gratifying to find appreciation in Boston, and I hope the painting may prove all that you desire.

A Rising Artist

Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts, called Elsie, was born in Philadelphia to a wealthy family. In 1889, the aspiring artist moved to Paris where she studied painting and received critical praise. After nine years in Europe, Elsie returned to America and began exhibiting her work in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York.

Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts Painting in Her Studio, 1903

Concord, Massachusetts

While vacationing in New Hampshire, Elsie met her lifelong partner Grace Keyes, an outdoor enthusiast and athlete—she was the Massachusetts women’s golf champion in 1900. The two women purchased a home together in Grace’s hometown of Concord, Massachusetts.

Concord is an ideal place for work and should you care to run out here sometime it would give me pleasure to show you my studio.

An Outspoken Activist

Roberts’ placid, 1915 landscape belied the turbulence of contemporary events. Elsie—like Isabella—was troubled by the outbreak of World War I in Europe. To raise money for the war effort, Elsie organized exhibitions of local Boston artists in Concord Center. All proceeds went directly to victims of the conflict. She raised enough funds to sponsor an ambulance through the American Field Service (AFS) which ferried wounded soldiers from Paris train stations to hospitals.

Read more about the AFS and Isabella’s sponsored ambulance on the blog.

Isabella Stewart Gardner’s ambulance with the American Field Service, a bout 1916

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Elsie also used her artistic practice to benefit the war effort. She painted pictures of the women of Concord who knit over a thousand mufflers, socks, and fingerless gloves for Belgian refugees living in England. Roberts donated the profits of these paintings to supply wool for the refugees to make their own clothing to wear or sell.¹

Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts (American, 1871–1927), Women Sewing for Belgian Refugees, 1915. Oil on canvas on board, 10 ¾ x 13 ¾”

Permanent Collection, Concord Art, Concord, Massachusetts

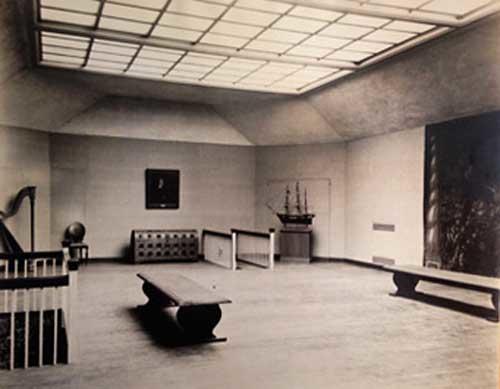

After the War ended, Roberts continued to support the Concord community and local artists. She founded the Concord Art Centre (now the Concord Center for Visual Arts) in 1922 “to promote and advance the visual arts, artists and to sustain a cultural community.”² She purchased the historic John Ball House in the town’s center and hired Lois Lilley Howe—one of the first professionally trained women architects in Massachusetts—to renovate the building for exhibitions of contemporary artists including Claude Monet, John Singer Sargent, and Mary Cassatt.

A Life Turned Legacy

Elsie’s personal and professional successes did not protect her from depression. When doctors advised her to stop painting after a surgery, she was despondent. In 1926, she was diagnosed with psycho-neurosis (probably anxiety or depression). A year later, she died by suicide at her home at the age of 57. Her partner Grace—one of the original Trustees of Concord Art—lived in their shared home until she died in 1950. She received interest from Elsie’s estate of $2 million dollars (about $31 million today) and the principal went to Boston’s Children's Aid Society in accordance with her will.

Just as Isabella’s legacy lives on at her Museum, Elsie’s legacy lives on at the Concord Center for Visual Arts which displays the work of contemporary artists and offers programming to serve the local community. To celebrate their centennial, they are featuring a retrospective exhibition of their founder’s work, “Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts: Artist + Philanthropist 1922-2022” throughout the year.

The author is grateful to Kate James, the Director of the Concord Center for Visual Arts, for her help with this post.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Anna Coleman Ladd: Art Helping Veterans

Read More on the Blog

Sarah Wyman Whitman: Artist and Advocate

Read More on the Blog

Anna Hyatt Huntington: World War I Memorial to the Sons of Gloucester

¹ See Kate James, "EWR and Concord Art's Roots," Concord Journal (November 13, 2014). Accessed at https://concordart.org/history/

² See the mission statement for the Concord Center of Visual Art at https://concordart.org/about-concordart/