Each object in the Gardner Museum has a story behind it, though these stories are often hidden. That is by design; Isabella Stewart Gardner wanted visitors to create their own stories and connections rather than be given a clear narrative to follow. It makes visiting the museum—and returning again and again—an adventure full of surprises. When I started as a Gardner Ambassador, I was taken aback, but also happy, to find connections between my military service and a museum best known for its priceless paintings and sculptures. There are letters, photos, and other memorabilia from World War I on display in the Macknight Room. Many of these came from one of Gardner’s closest friends, A. Piatt Andrew.

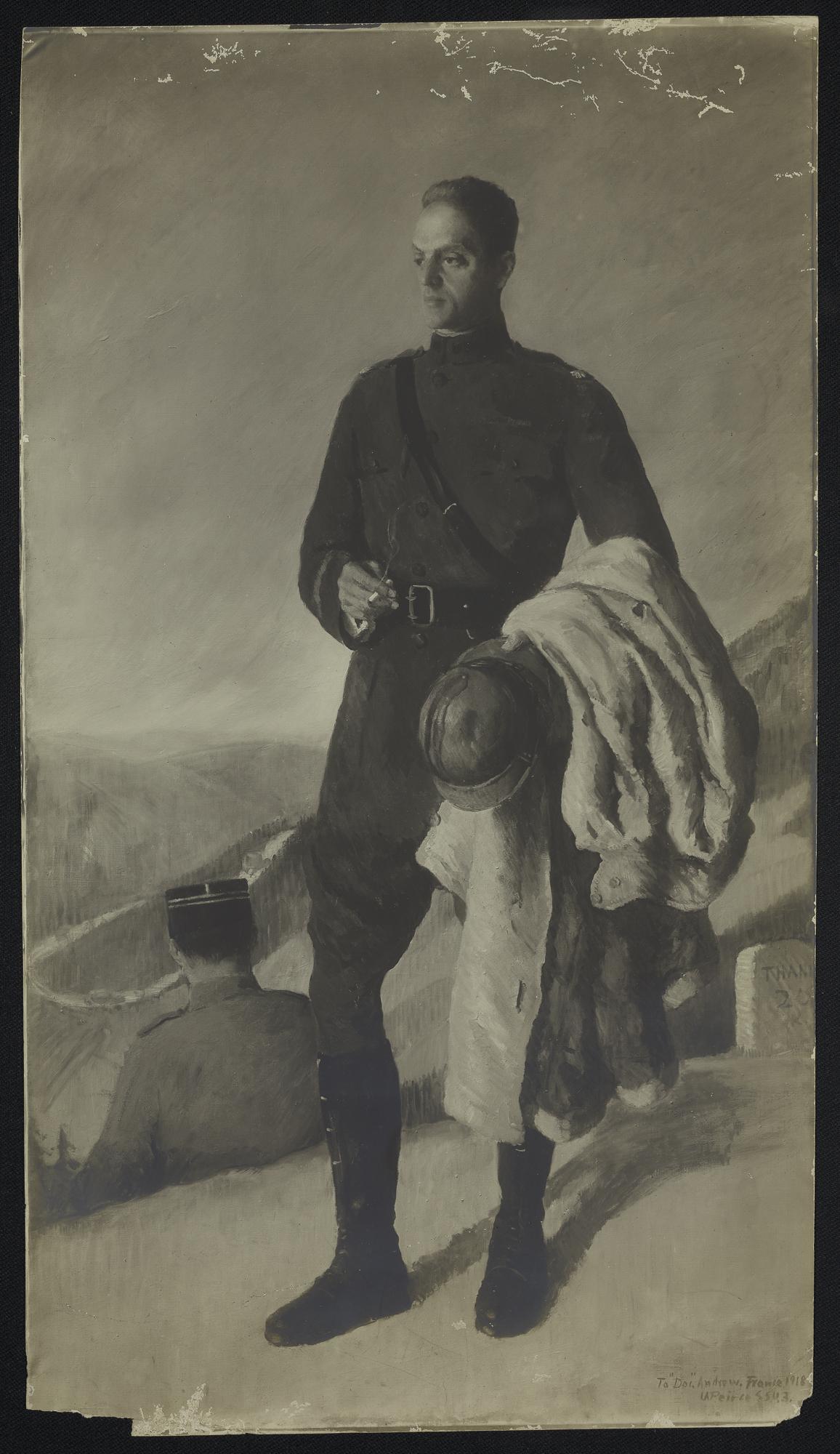

Anders Zorn (Swedish, 1860–1920), Abram Piatt Andrew Jr., 1911. Oil on canvas

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See it in the Blue Room.

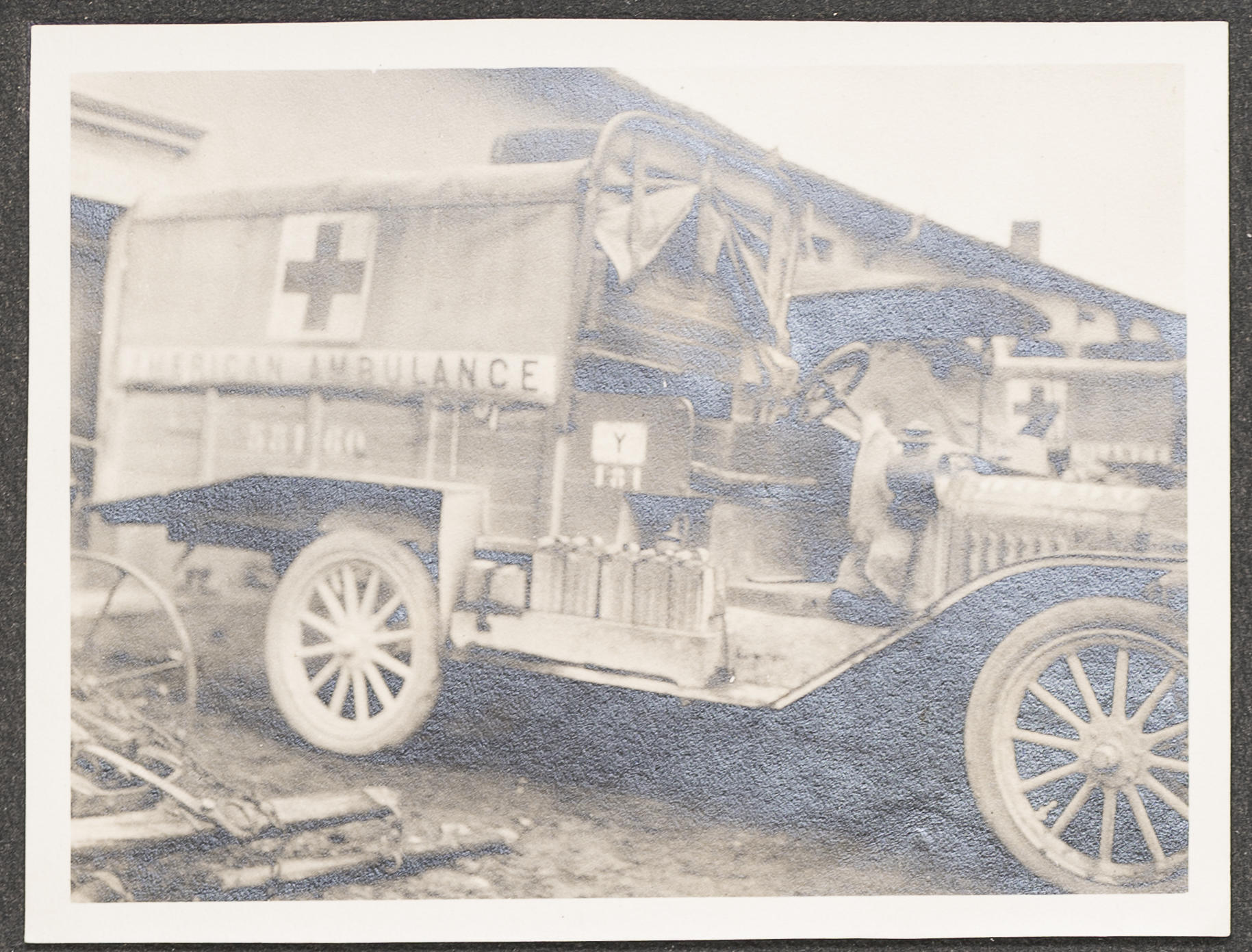

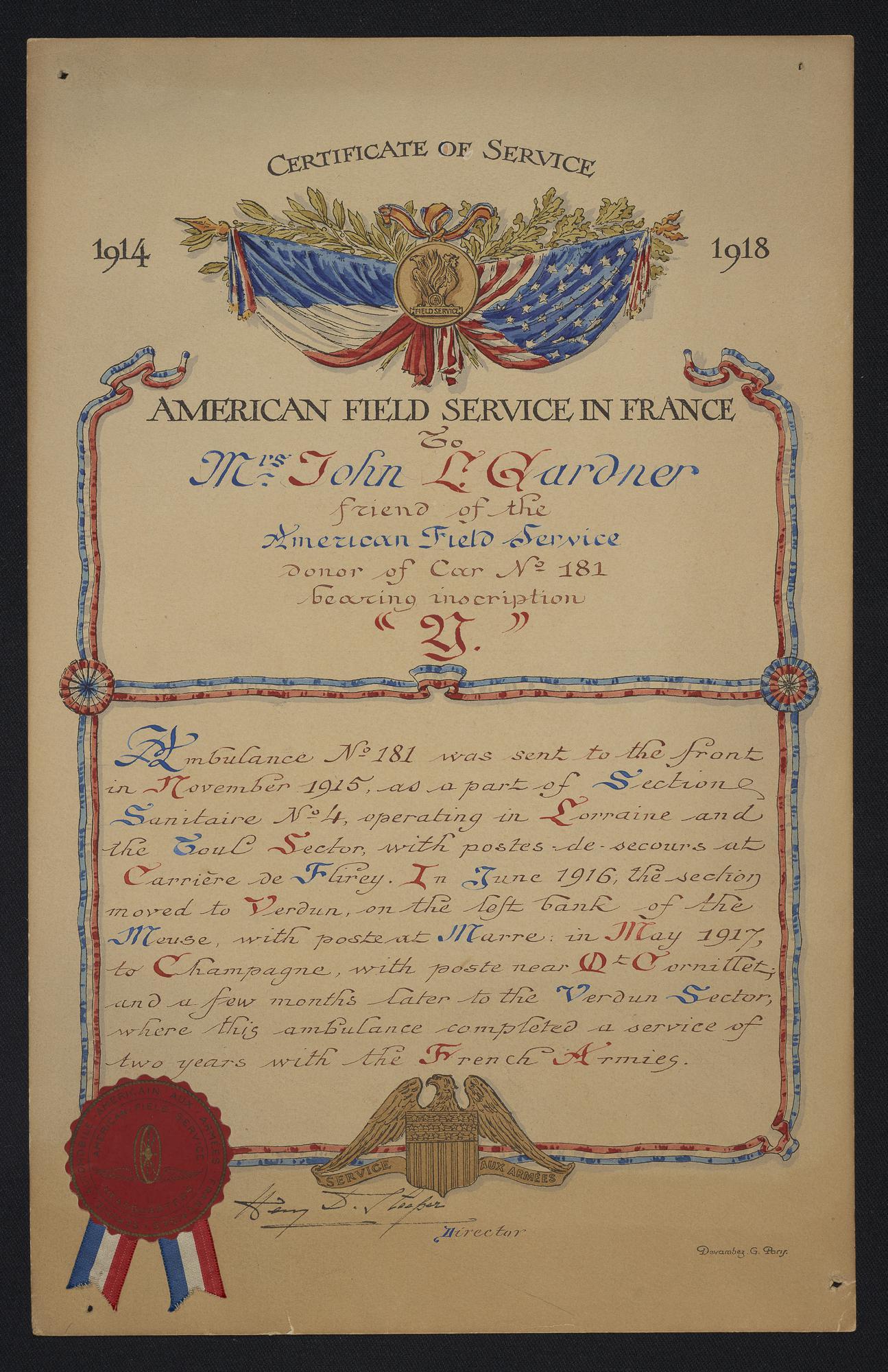

Andrew, who went by APA, was one of the hundreds of American volunteers to support the Allied efforts in WWI before the United States officially entered the conflict. In 1914, he left Massachusetts for France. Shortly after his arrival he co-founded and began his service as an ambulance driver in the American Field Service (AFS). This charitable organization was dedicated to funding and running ambulances to transport injured soldiers and civilians to the American Military Hospital. It was funded by private donors, one of which was Isabella herself. She sponsored an ambulance named “Y” after her nickname “Ysabel,” a reference to Isabella I of Spain.

After being appointed Inspector General of the AFS in 1915, APA met with French Captain Aimé Doumenc to argue for American presence on the front lines. Up until this point, France had prohibited foreign internationals from entering into combat zones. The two agreed to a trial of APA’s proposal that American ambulance drivers would pick up injured soldiers from the front lines, leading to an overwhelming success. This led to the AFS operating under the purview of the French Army Command until it was absorbed by the U.S. Army Ambulance Service in 1917, when the U.S. officially entered the conflict. During this transition from a volunteer-based service to a government-based one, APA was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army.

Francois Antoine Vizzavona (Italian, 1876–1961, photographer), Waldo Pierce’s Portrait of A. Piatt Andrew in his AFS uniform, 1918–1922

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.009228)

Despite the distance, stress, and wartime responsibilities, APA continued his correspondence with Isabella throughout the war. During his time in France from 1914 to 1919, he sent numerous letters and postcards to her. He even sent his friend a pencil made from a bullet shell that he received from a French soldier in 1915.

Not only did APA stay connected with old friends while in France, but he made new ones. One might not expect participation in stressful war efforts to serve as a breeding ground for friendships; yet, according to correspondence from APA this happened several times. Over four years of letters, there are consistent mentions of friends both new and old. He even ends one letter from 1915 by remarking, “I am very well and never so happy, with a lot of new and already established friends.”

These letters and postcards, when presented as a whole, create less of an account of war and more of a travelogue. In some letters he gushes about his love for Paris and records the effects of the war on the city. In others he describes the beautiful scenery he encounters while driving through the Vosges mountains and Alsace, which were the sites of some of the fiercest fighting. This isn’t to say that his service was without its struggles and grief, but rather that his role as an American volunteer insulated him from the danger and trauma that most soldiers experienced.

APA’s volunteer role was one typically filled by men, though there were women ambulance drivers during WWI. There was a lot of pushback towards women drivers due to the gender norms of the time. The numerous sexist barriers to service included, but were not limited to, doubts about whether they could drive as well as men or handle the physical demands of the job.

It’s interesting to compare both APA’s experiences and the women drivers’ experiences to my own. About a century after these women served, I enlisted in the U.S. army as a motor transport operator (a truck driver). The amount of sexism, though unfortunately still present, had greatly decreased. While I did have to perform tests to make sure that I could operate vehicles and carry heavy equipment, these tests had gender neutral standards; all truck drivers had to complete them.

Unfortunately, in addition to the sexism they faced at the time of their service, women are often omitted from WWI-centered media and analysis. Though there have been efforts in recent years to provide more focus on women’s contributions, these haven’t been as effective as one might hope. The norm is still a pattern of minimization and omission, which has extended to Isabella herself. Though there was initial recognition of her financial contributions to the AFS during and just after WWI, this part of her story only appears rarely in more recent discussions and analyses of her accomplishments and contributions.

American Field Service (founded Paris, 1915), Certificate of Service for Ambulance 181, “Y,” 1918

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.009194). Isabella kept this certificate in her desk in the Macknight Room

Comparing these omissions in Isabella’s story with the glorification of APA’s wartime service prompts questions about continued sexism in how we tell the histories of war. Nonetheless, in the museum, where Isabella could establish her own stories and histories, she made sure to include clues for attentive visitors about her participation in World War I. Similar to other aspects of the museum, it was a way to center a woman’s perspective. It was a forward-thinking action on her part because she preserved momentos of her wartime efforts alongside those of her friends with military service. Though our experiences are different, I appreciate being able to see these traces of history and connect them with my own.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Anna Coleman Ladd: Art Helping Veterans

Learn More

Gardner Ambassador Program

Read More on the Blog

Ned Gourdin: An Exceptional Bostonian