Guanyin, who across cultures is venerated with different names, including Avalokiteśvara and Kannon, is the Bodhisattva of Compassion. In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a being who can achieve enlightenment but remains on Earth to help others achieve enlightenment. Buddhism originated in India more than 2,500 years ago. At first, bodhisattvas were genderless or represented as male, but later, especially in late imperial China, Buddhists started depicting Guanyin as female. One reason for this gender fluidity is due to the way a bodhisattva has the ability to manifest on Earth in many different forms.¹

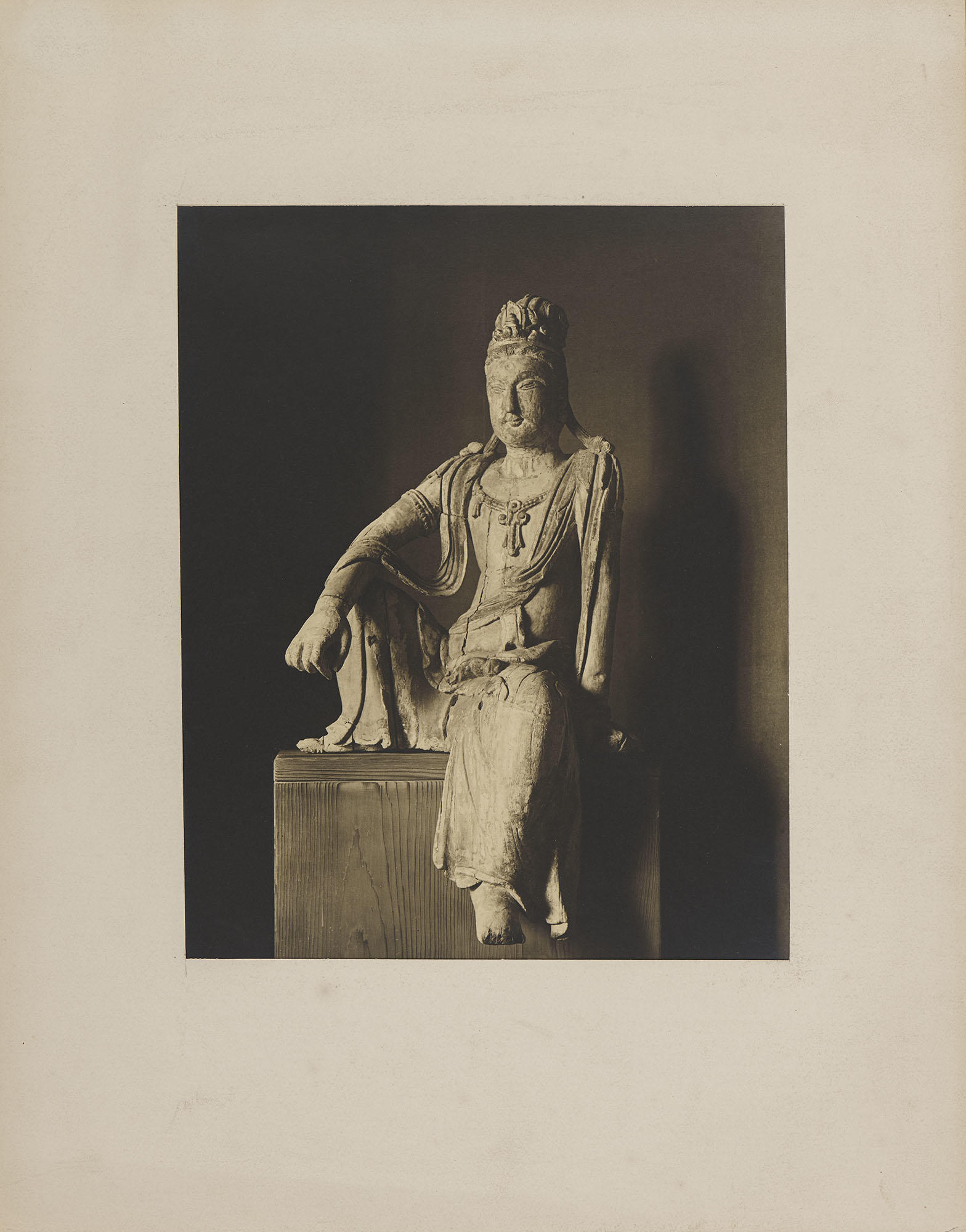

The Gardner’s sculpture of Guanyin is dressed in the rich clothing of an Indian prince, including flowing pants tied with a knotted sash and a gilt-trimmed scarf wound around the body. The figure is further decorated with an ornate gold necklace, bracelets, armbands, and a multi-colored crown depicting the Buddha Amitābha. Guanyin strikes a relaxed sitting position known as the pose of “Royal Ease”. The figure sits with the right arm casually resting on the upright bent right knee, while the left leg hangs down in front, and the left hand rests next to the body to support the figure.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S8w1). See it in the Chinese Loggia.

Chinese, Guanyin, late 11th century–early 12th century. Painted Paulownia wood with remains of gilding: 116.8 x 66 cm (46 x 26 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased the sculpture in 1919 from the New York City dealer, Parish-Watson & Co. Inc and displayed it over the entrance to her Chinese Room, which was a semi-private, subterranean gallery that once exhibited her extensive collection of Asian art.

Because the Gardner Museum’s 11th-mid 12th century Guanyin is one of the most important pieces of art in the collection, the Conservation department designed a technical study to learn about the sculpture’s surface decoration layers, wood substrate, and construction method. Multiple analytical techniques were used, ranging from low-tech close examination with a magnifier, to high-tech imaging using CT scanning at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Read on to discover some of the highlights we learned using various techniques!

Close Looking

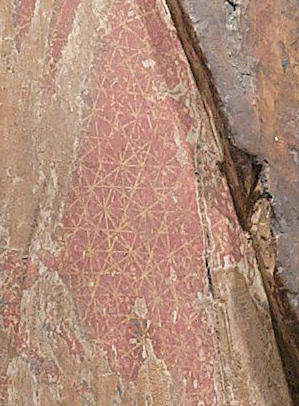

One of the best parts about a technical study is looking deeply at a work of art. To aid in close looking, we use different light sources and magnifiers like an OptiVisor. One of the discoveries from close looking was a fine gold geometric pattern on the back of Guanyin’s pant leg, which was subsequently covered over by a second layer of paint. The geometric pattern was created by cutting thin strips of gold leaf and gluing them down to create the design, a technique often referred to by its Japanese name, kirikane.

Infrared Imaging

Infrared imaging is a non-destructive photographic method that detects carbon-based materials such as charcoal, graphite, and ink that are often below varnish and paint surfaces. The infrared image of Guanyin’s face showed black concentric circles painted on the chin, representing a beard.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S8w1)

Chinese, Northern Song, or Jin dynasty, Guanyin, late 11th century–mid 12th century, infrared image of Guanyin’s face

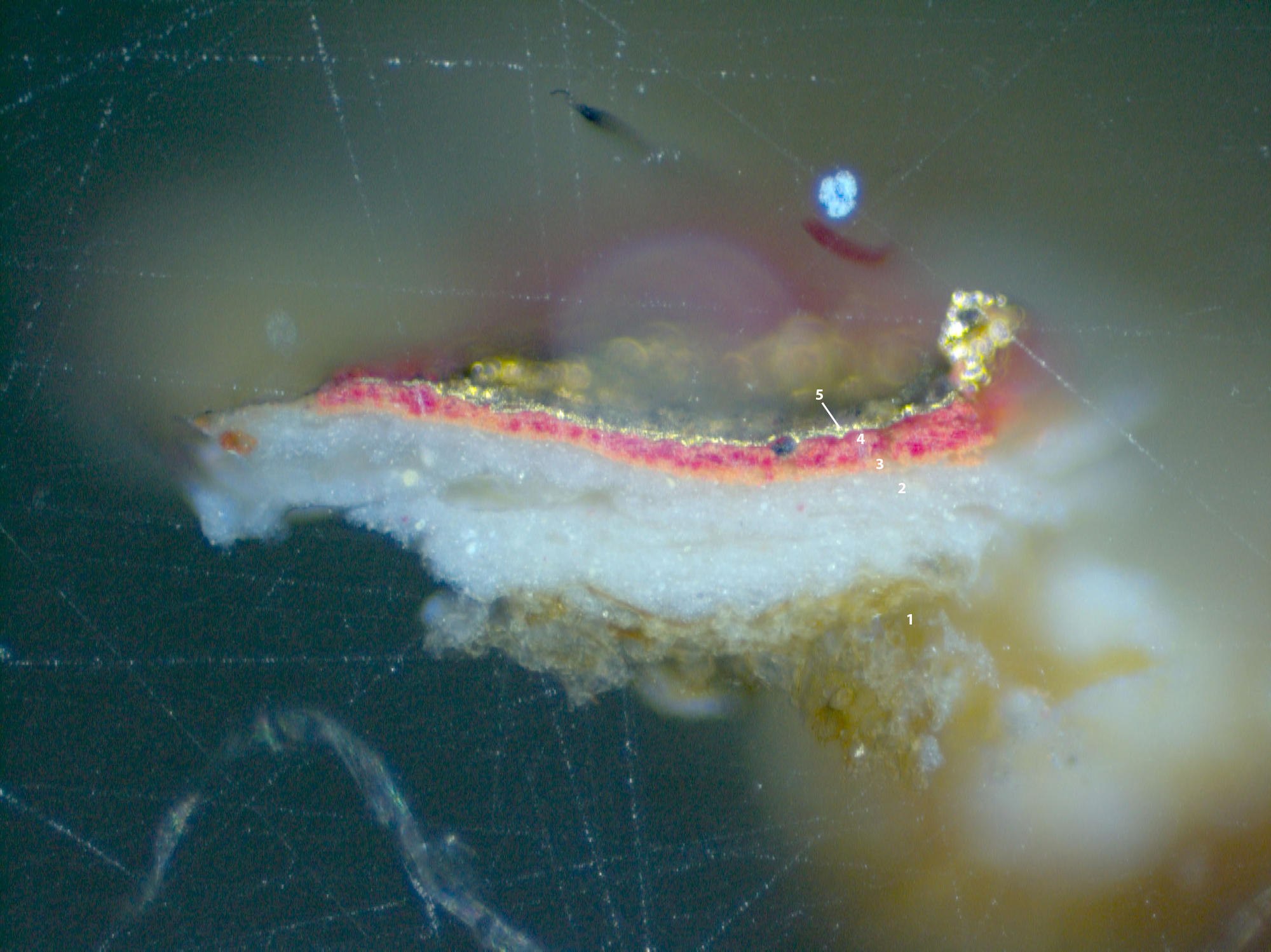

Paint Cross Sections

In general, art conservators try to learn as much information as possible about an object without disrupting any material. However, sometimes taking a small sample, a couple of millimeters in size, can reveal a wealth of information. We removed a tiny paint sample from an area of kirikane decoration on the red pants and mounted it in a cube of resin that was polished to reveal the cross section. We observed the sample under a microscope to examine different layers of paint and decoration. At the bottom there is a small amount of wood. Above the wood there is a thick, sparkly, white layer of ground preparation which makes the surface smooth for painting. Above the white are two distinct layers of paint, orange then red and finally, we see the gold leaf at the top.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S8w1)

Magnified cross section image showing layers of decoration, paint, ground, and wood from the Gardner Museum’s Guanyin

Scanning Electron Microscopy

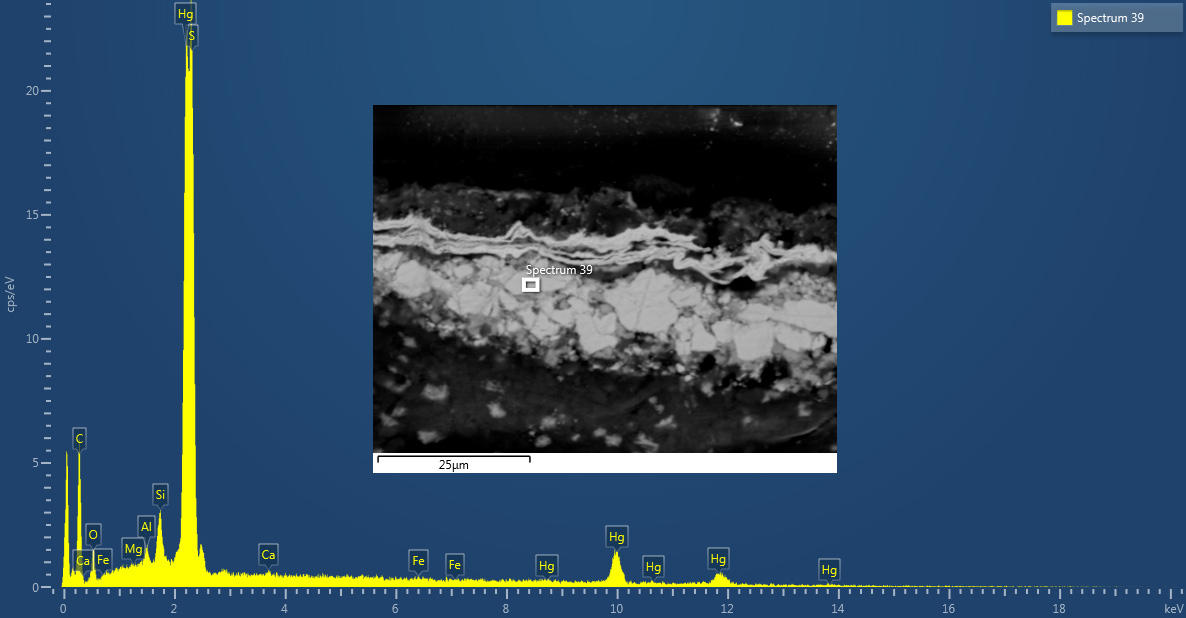

We also collaborated with Richard Newman, Head of Scientific Research at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to carry out scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SEM allows you to see at much greater magnification than a regular light microscope. For instance, the scale bar at the bottom of this SEM image of the same paint cross section shown above is 25 micrometers, which is about the size of a white blood cell! At the top of the image there are a bunch of wavy lines, which are actually the thin layers of gold leaf that have been repeatedly folded, making it thicker and therefore easier to cut and handle for the kirikane decoration.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Elemental spectrum with peaks for sulfur and mercury with an inset highly magnified black and white image of the paint cross section sample from the Gardner Museum’s Guanyin

SEM analysis can also give elemental information. Analysis of the red paint layer revealed the presence of the elements sulfur and mercury, which are characteristic of the red pigment, vermilion.

Wood Sampling and Radiocarbon Dating

We also wanted to learn about the wood used to create the sculpture. Previous wood analysis carried out in 2016 identified it as Paulownia wood. Paulownia is a fast growing tree that is native to China and has a characteristic hollow pith in the center. It is a light-weight wood that is soft and easy to carve. Many other Guanyin sculptures have also been carved out of Paulownia wood.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Underside of the Gardner Museum’s Guanyin sculpture showing the growth rings of the Paulownia log and the hollow pith center

To confirm the date of the sculpture, we used radiocarbon dating, also sometimes called carbon-14 dating. Radiocarbon dating is a scientific method that can accurately determine the age of organic materials based on the decay of the carbon-14 isotope. We sent two samples to the University of Georgia’s Center for Applied Isotope Studies, one sample was from the innermost tree ring and the other was from the outermost tree ring. The date we received is really the date that the tree was cut down, but we assume that the carving of the sculpture would have happened soon thereafter. The results came back with a date range of 1090-1150 CE which aligns well with the 12th century date based on art historical context.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

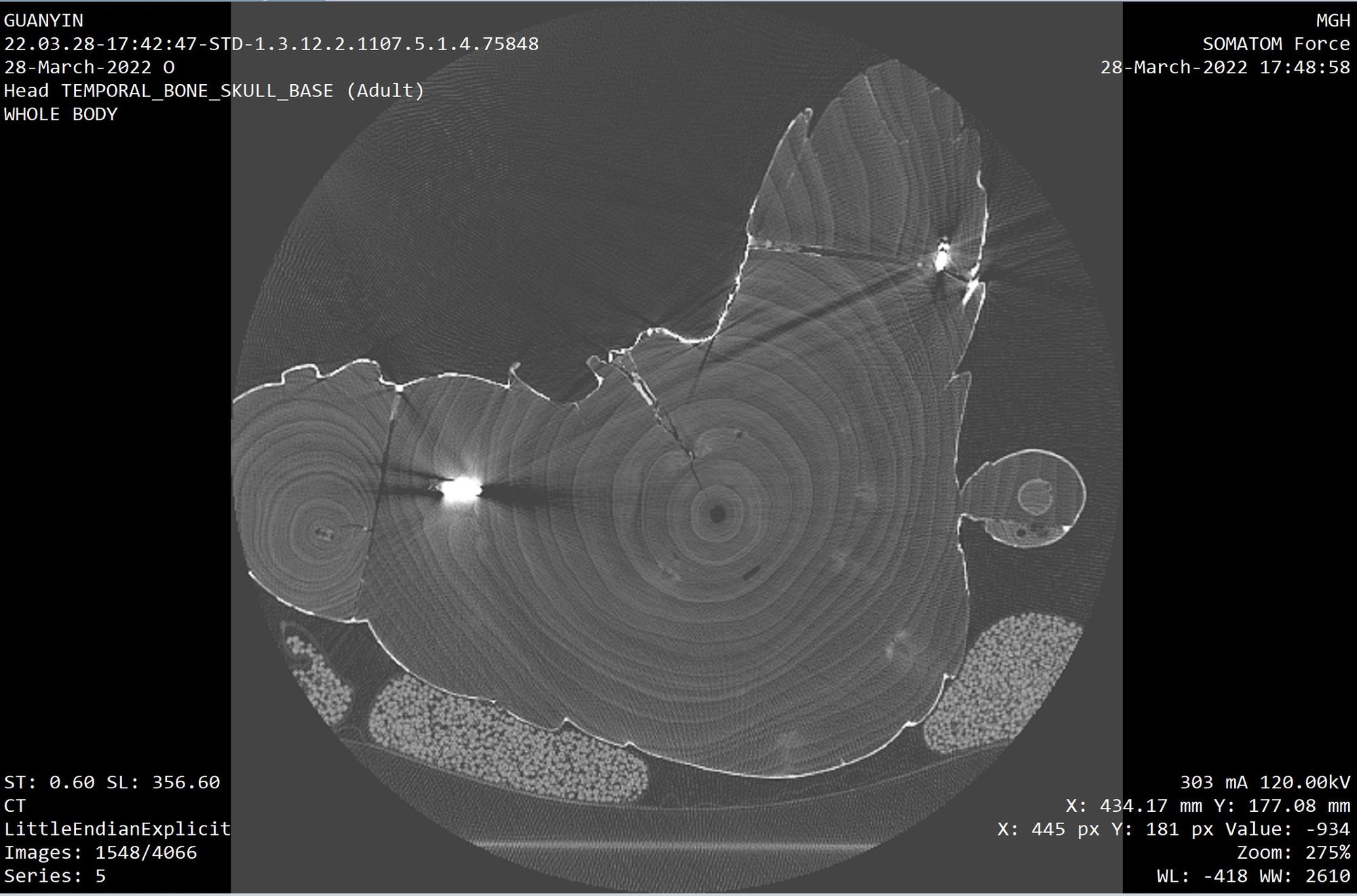

Computed Tomography Scan

We transported Guanyin to MGH for a computed tomography (CT) scan! A CT scan is a non-invasive procedure that takes many X-ray images from all different angles as the patient (or sculpture) passes through the machine on a motorized table. A computer reconstructs all the individual images into cross-sectional images or slices. These images can be viewed as slices or put together into 3-D models. We hoped to find out if there were any hollowed out cavities inside Guanyin and about the construction method used to attach the different pieces of wood. It was not uncommon to place ritual objects or sutras inside of Buddhist sculptures, but we did not find cavities inside Guanyin. In terms of construction, most of the wood pieces were attached with iron nails (some extremely large) and wood dowels, instead of woodworking joinery techniques. We also learned that the head, neck, torso and left arm that extends straight down are all carved from one log.

Hopefully you have enjoyed learning about some of the discoveries we’ve made about the Gardner’s Guanyin sculpture as well as understanding some of the tools and techniques that conservators use when they are studying art.

You may also like

Read more on the blog

Listening, Learning, Mediating: Isabella’s Journey with Chinese Art

Explore the Collection

Chinese, Votive Stele, 543 CE

Read more on the blog

Isabella in China

¹ For more, see Yuhang Li, Becoming Guanyin (University of Columbia Press, 2020).