Museums are not simply repositories of art. They humanize the landscape of human events. They connect us to life’s most enduring themes. I have long felt this way about the Gardner, and feel it particularly keenly about a work that will be specially presented at the Museum January 20–February 4, 2024.

I first encountered Steve McQueen’s Lynching Tree (2013) at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) in October 2022. Lynching Tree was unknown to me then and probably like many Americans, I knew McQueen principally as the producer and director of the powerfully affecting film, 12 Years A Slave, not as the highly decorated British visual artist that he is. McQueen was the first Black British producer and director to receive the Academy Award for Best Picture.

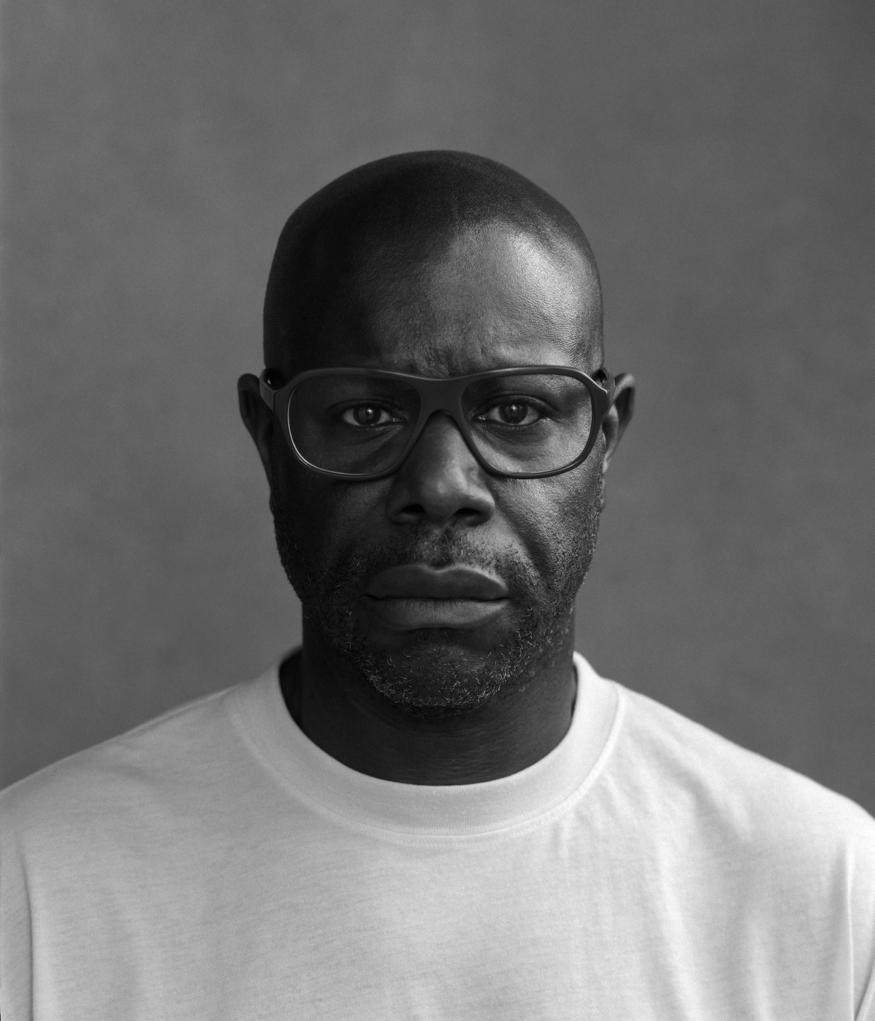

Steve McQueen: Photo by James Stopforth

With family roots in Grenada and Trinidad, McQueen was born near London in 1969. He is the recipient of the Turner Prize (Britain’s highest honor for a visual artist) and the Academy Award for Best Picture for 12 Years a Slave, and was appointed Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) for his contributions to art and public service.

In recent years, the YCBA, now under the leadership of Courtney J. Martin, an acclaimed African American scholar of African American historical and contemporary art, shifted its focus from introducing Americans to British art, history and culture to examining Britain’s role in empire building and slavery.

Lynching Tree, far removed from the busy galleries and exhibit spaces on the lower floors, was located on the YCBA’s top floor on a long wall off the stairs and elevators. It was the only work of art there because McQueen asked that it not be contextualized or in competition with other art objects.

Lynching Tree is a color photograph mounted in a lightbox that depicts an aged tree with thick, gnarled, sprawling branches. The tree stands in a clearing littered with leaves and grass and is surrounded by bushes and scrawny saplings. The lightbox illumination creates depth and eerie contrasts of the various elements of the natural setting. Ominous, dark shadows lie on the ground. The sky is gray, and an incandescent patch of sunlight spreads out at the foot of the tree.

Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Copyright Steve McQueen

Steve McQueen, Lynching Tree, 2013. Transparency and light-box, 85.4 x 105.09 x 13.02 cm (33 5/8 x 41 3/8 x 5 1/8 in.)

The landscape is neither pastoral nor bucolic. The light captured in the photograph and the light box cast dark shadows, creating a patina of gloom and foreboding. The landscape is grotesque and funereal, evoking disturbance and disorder. Something terrible has occurred here, buried, hidden beneath the blood-stained ground.

One notes that the title of the photograph is not The Lynching Tree, but rather Lynching Tree, signaling this is not a single or particularized event, but rather the rapacious universality of lynching Black people in America. Almost 4,500 Black people were killed in terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950.

While at the YCBA, I sat on a single bench placed about 10 or 12 feet in front of Lynching Tree. I was alone in the gallery, except for MIT Professor Karilyn Crockett, who had led me on a surprise visit to the YCBA. It was a gift, for which I remain grateful. Because there are no other objects or labels on the stark, white walls, the visitor’s gaze is focused on a single work of art without competing distractions. The art singularly engaged me or more properly, we engaged each other in mute conversation.

As I sat there in silence for several minutes, my mind was racing to keep up, to understand what was in front of me. Eventually, I was able to comprehend with a sense of immediacy the unimaginable truths buried beneath—now invisible, but not forgotten. The truth of what I was witnessing, summoned from deep ancestral places of grief and dread, gave way, first, to tears and then, to heaving, convulsive sobs. I was there now. I could see, hear, taste and smell the horror—the shock of what had taken place here. And I thought of my great grandparents, the son and daughter of enslaved parents, who made a meager living on the red clay fields near Little Rock, Arkansas, where important civil rights battles over the soul and dignity of this nation were waged. I thought of Black bodies invisible, unseen. I thought of the people living in this land of plenty who, in the words of Lee Rainwater, author of Behind Ghetto Walls: Black Families in a Federal Slum," are constantly exposed to the evidence of their own irrelevance.” I thought of my work at The Boston Foundation and my commitment to improving lives and strengthening communities. And, most of all, I thought of my own children.

Put simply, McQueen’s Lynching Tree is a remembrance, a memorial, a monument of lives lost, bodies broken and memories of slavery’s brutality that defiled the American landscape that lies right beneath our feet—the terrible and horrific injustice that we could see, if we only we had the courage to do so.

Then, relief came when the docent, who seemed to appear out of nowhere, placed his hand on my shoulder and gave me a box of tissues. “Thank you,” I said without looking up.

As I later learned, Steve McQueen took this photograph on a piece of land now called Magnolia Lane Plantation near 9 Mile Point, along a bend in the Mississippi River outside of New Orleans. The tree is on the location of McQueen’s film shoot, but it is not the primary tree used in the movie. When McQueen learned enslavers had used this oak as a hanging tree, and that the small mounds in the undergrowth of the tree might be graves with no headstones, he decided to reshoot a scene of 12 Years a Slave in this place. In the scene, the enslaved protagonist Solomon Northup, attempting to run, witnesses a group of white people lynching two Black men.

It's what made the scene even more vital and necessary—bringing the past into the present. If this tree had eyes, imagine what it has seen...Just out of respect, we said a few words before we started shooting here.

Lynching Tree is a truth-teller. It is emblematic. It calls on us to look history square in the face and not turn away—but rather see a thing as it truly is in itself—so that we might, if we have the courage to do so, first acknowledge and then, seek to repair the harm that has been done. There are untold stories in the landscape, and, in some parts of the country, there are organized and even government-sanctioned efforts to erase these stories, to obliterate them from our history.

For several weeks, my Lynching Tree experience stayed with me. Thinking that I wanted to approach a Boston museum to host an exhibit, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum came readily to mind. The Gardner would provide what I had experienced at Yale: an intimate setting—one where Lynching Tree wouldn’t be swallowed up by competing exhibits. Moreover, the Gardner’s famed Courtyard could be, as they say, usefully in conversation with McQueen’s natural setting.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

Courtyard

Isabella Stewart Gardner has created a series of intimate spaces within her galleries that invite close looking at specific, emotive works. Specifically, the Gardner staff reminded me that these intimate spaces include, for instance, paintings placed on desktops with a chair in front of them, such as Christ Carrying the Cross by the circle of Giovanni Bellini in the Titian Room. You can see similar arrangements in the Raphael Room, Dutch Room, and Tapestry Room. Though these spaces were designed for historic art, I knew there were other spaces within the Museum that could create contemplative moments for contemporary art.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The Titian Room, showing the contemplative installation of the Circle of Giovanni Bellini’s Christ Carrying the Cross

In addition to thinking about the Gardner’s particular setting, I thought of its groundbreaking programing—like the Larger Landscape Conversation, Black Landscapes Matter, which I had attended. The panelists interrogated Black landscape and the dissonance between beauty and horror in the settings of former violence and the ability of nature to hold memory.

Courtesy of Ally Schmaling, on behalf of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Panelists Kofi Boone, Walter Hood, and Sara Zewde hosted by the Gardner's Ruettgers Curator of Landscape Charles Waldheim in the Larger Landscape Conversation “Black Landscapes Matter” in Calderwood Hall, 10 March 2022

I contacted Peggy Fogelman, the Museum’s Norma Jean Calderwood Director, to see if the Gardner would consider hosting Lynching Tree as an exhibit. Happily, her curatorial staff and she quickly agreed that a special viewing offered an opportunity to show the work and host critical conversations about the legacy of slavery in the United States. The exhibition’s timing was determined to align with the lender’s and artist's agreement as well as the Museum’s exhibition schedule, which is typically planned 3–5 years in advance. Due to the Gardner’s prior exhibition commitments to artists and institutions, it would have had to wait almost five years if it wanted to show McQueen’s piece for a three-month run. Therefore, the Gardner leaned into the urgency of this presentation, given the importance of its theme. A decision (with which I agreed) was to exhibit it sooner rather than later, and to figure out how best to do that within an exhibition schedule established years in advance. When the work was exhibited at the Yale Center for British Art, it was installed by itself for a period of 4 weeks—the Gardner’s installation is 2 weeks. I am enormously grateful to Peggy and her remarkable staff for accommodating this special presentation.

While I knew about the Gardner’s physical spaces and programming when I approached them about showing this work, I was interested to learn recently that Isabella was friends with people who advocated against the violence of lynching. She honored her friend, the activist John Jay Chapman (1862–1933), in the Museum in the Crawford/Chapman Case in the Blue Room, just steps away from where Lynching Tree will be exhibited. In 1912, on the one-year anniversary of the lynching of Zachariah Walker in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, Chapman gave a speech, "A Nation’s Responsibility," at Coatesville, in which he called lynching "one of the most dreadful crimes in history" and said "our whole people are...involved in the guilt.” It feels fated that McQueen’s work will appear within feet of an installation dedicated to Chapman.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The Crawford/Chapman Case in the Blue Room, 2022

Ultimately, Lynching Tree exemplifies that art is not the exclusive provenance of a few, but rather it is a life-affirming possession of the many. I am grateful that Boston audiences will get to experience it in this Boston setting.

You May Also Like

Special Exhibition

Steve McQueen: Lynching Tree

Audio Guide

Courtyard Meditation

Learn More

Contemporary Art at the Gardner