Dubbed by American author Henry James “a mighty poet,” Titian remains one of the most celebrated painters in European art. When Isabella began collecting old master paintings in 1891, Titian quickly rose to the top of her list. Landing a great one required a rare combination of fierce determination, timing, and luck. This is the acquisition story behind The Rape of Europa (1562), one of the most influential and iconic Renaissance paintings in America. The purchase of Titian’s masterpiece from an English aristocrat marked the beginning of a new phase in Isabella’s business relationship with scholar and art dealer Bernard Berenson, and made her the envy of every art collector in the United States.

Titian (Italian, about 1488–1576), The Rape of Europa, 1559–1562. Oil on canvas

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See it in the special exhibition “Titian: Women, Myth & Power,” August 12, 2021 - January 2, 2022 or in the Titian Room.

Titian’s Rape of Europa belonged to the 6th Earl of Darnley and hung in Cobham Hall, his palatial home immortalized by Charles Dickens in The Pickwick Papers (1836) and celebrated for an art gallery purpose-built to showcase the spectacular collection of paintings assembled by his ancestors in happier days. Like the rest of the aristocracy saddled with plummeting revenues from their vast estates, he had already sold six of his finest Venetian pictures to London’s National Gallery. Yet this solution proved only temporary. Facing the punishing consequences of new death duties introduced in 1894 as well as the financial drain of an heir who spent money like water, the embattled earl continued selling off the family art treasures to pay his bills.

The Long Gallery at Cobham Hall, Kent, 1904

Country Life Images

The disposal of a painting as important as Europa from a man as proud as Darnley was easier said than done. London’s premier art gallery, Colnaghi and Company, had been trying for over a year to find a buyer. Between 1894 and 1896, the gallery offered it unsuccessfully to two museums for £15,000. Following a rejection from the National Gallery—whether for financial reasons or because their buttoned-up board found the subject too risqué—Colnaghi turned to the National Gallery’s principal competitor, Wilhelm von Bode, director of the newly established Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (now the Bode Museum) in Berlin. Bode, as notorious for haggling as for connoisseurship, made a one-day trip to Britain solely for the viewing at Cobham Hall. To Bode’s dismay, he did not possess the financial resources to meet Darnley’s demands. The obstinate earl’s unwillingness to negotiate, combined with his increasing expectations, left little doubt that the painting’s colossal asking price would only be met by an American collector.

On 19 February 1896, the Colnaghi gallery’s aptly named junior partner Otto Gutekunst (translating literally to “good art”) wrote to Isabella’s principal art advisor Bernard Berenson:

It would be jolly if Europa came to America, Eh?

Berenson did not miss the opportunity to satisfy Isabella’s ambitions for landing an important picture, or what she later called “a whacker.” At £20,000 (about £2.3 million today), Europa must have seemed a comparative steal: “...I am dying to have you get the Europa.... No picture in the world has a more resplendent history, and it would be poetic justice that a picture once intended for a Stewart should at last rest in the hands of a Stewart.” Ever the cunning salesman, Berenson deliberately misspelled the English royal house of Stuart, linking Isabella to its infamous queen Mary I, who married Titian’s patron Philip II. Berenson’s sales pitch played on his friend’s genealogical fantasy that she had descended from royalty.

Isabella leapt at the chance, agreeing to the purchase for £20,000 and setting a new record for any old master painting.

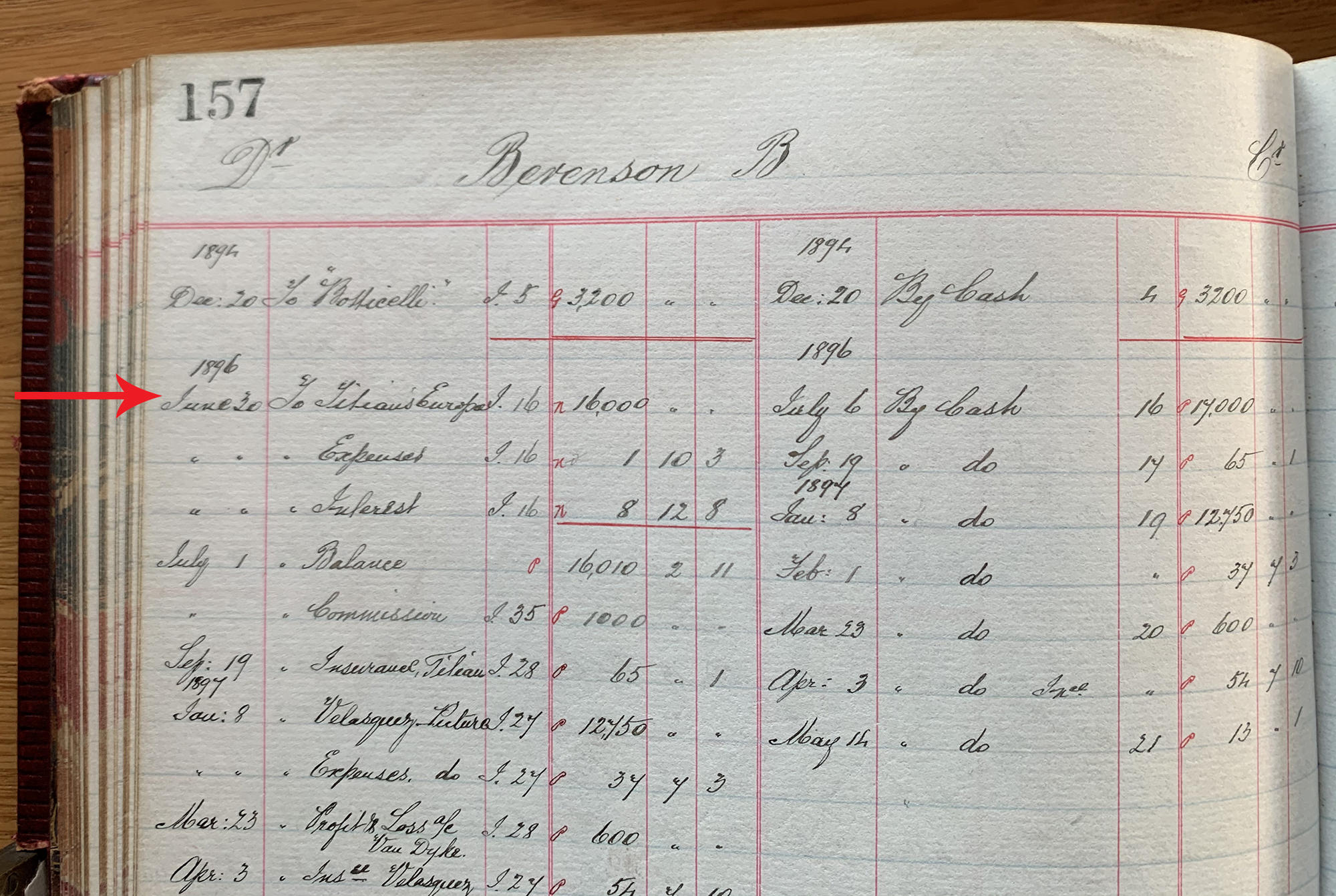

Colnaghi ledger showing the price of Titian’s Rape of Europa, 1896

Courtesy of P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London

As August approached, Gardner and Berenson celebrated their triumph like giddy children. Isabella wrote to him in London, “I am feverish about it. Do come over, just to unpack her and set her up in her new shrine! Do! . . . Shan’t you and I have fun with my museum?”

Isabella, anxious for the arrival of her great Titian, turned to her annual Maine pilgrimage for further distraction. On Roque Island, a remote isle near the Canadian border inherited from Isabella’s husband Jack’s Peabody relatives, she chased seals and “lived in a canoe.” Even these daily diversions, however, could not take her mind off the painting: “we go back to civilization . . . in two days. And then perhaps Europa may arrive!”

Isabella Stewart Gardner and her niece Olga Monks (paddling) in a birch bark canoe named “The Owl” in the Roque Island Maine archipelago, about 1896

Permission of RIGHC

Europa finally slipped into Boston in late August, arriving to empty streets and little fanfare. Isabella installed the painting in pride of place in her home at 152 Beacon Street, in the Red Drawing Room between the fireplace and a large window where it would receive copious natural light (although eventually she brought in an electrician “to arrange for Europa’s adorers, when the sun doesn’t shine”). Berenson’s promises did not disappoint. Breathless, Isabella wrote, “I have no words! I feel ‘all over in one spot’ . . . I am too excited to talk.”

Thomas E. Marr (Canadian-American, 1849–1910, photographer), Titian’s Rape of Europa installed in the Red Drawing Room at 152 Beacon Street, Boston, 1900

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (Marr2062)

As Bostonians returned from their summer holidays, Isabella’s news coursed through the grapevine, and visitors began to pour in. Painters, collectors, and friends came to pay homage as Europa put “adorers fairly on their old knees—men of course.” The response was overwhelming, quickly converting any who doubted its quality or authenticity. Newspapers caught wind of something big. As their gossip columns reported vague hints of a famous Titian bought by an anonymous American, rumors abounded. According to some, Isabella admired Europa from a bearskin rug beneath it, projecting herself into the painting of the Phoenician princess. She relished her masterpiece as much as the gossip, writing to Berenson, “I am back here tonight . . . after a two days’ orgy. The orgy was drinking myself drunk with Europa.”

Titian Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Photo: Sean Dungan

The arrival of Europa renewed Isabella’s commitment to build a collection for the public benefit. Several weeks later, she met with Willard Sears to explore the possibility of converting 152 Beacon Street into a museum with a residential apartment above. While Isabella insisted that he keep the building plans secret, she shared them with Berenson who dreamed of acquisitions for the future museum—nicknamed Borgo Allegro (the happy place). Isabella ended up building her museum in the Fenway neighborhood of Boston and dedicated a gallery, the Titian Room, to her greatest Renaissance painting—The Rape of Europa.

You May Also Like

Buy the Book

Titian’s Rape of Europa

Visit the Exhibition

Titian: Women, Myth & Power

Learn More

Titian Room Restoration