As the threat of invasion loomed over U.S. coastal cities in the early 1940s, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum took extraordinary measures to protect its priceless collection during World War II.

In 1941, the Gardner Museum joined a group of six Boston-area museums to form the Committee for the Protection of Valuable Objects to share information on the protection and evacuation of museum collections. This committee became part of the Planning and Technical Division of the Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety. Despite being part of a state-backed committee, the Gardner Museum faced a unique challenge: unlike other museums, its collection is always on display with no large-scale storage space readily available.

Finding a Hiding Place

Evacuating the Museum's collection became a necessity after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war on the United States by Germany and Italy in December 1941. After searching for a temporary storage space in museums farther west, Museum director Morris Carter secured a solution closer to home: a private citizen offered their garage in Center Harbor, New Hampshire, as a repository. This was no ordinary garage though: it was part of a large estate owned by Mr. and Mrs. Ernest B. Dane, prominent Boston-area art collectors and philanthropist.

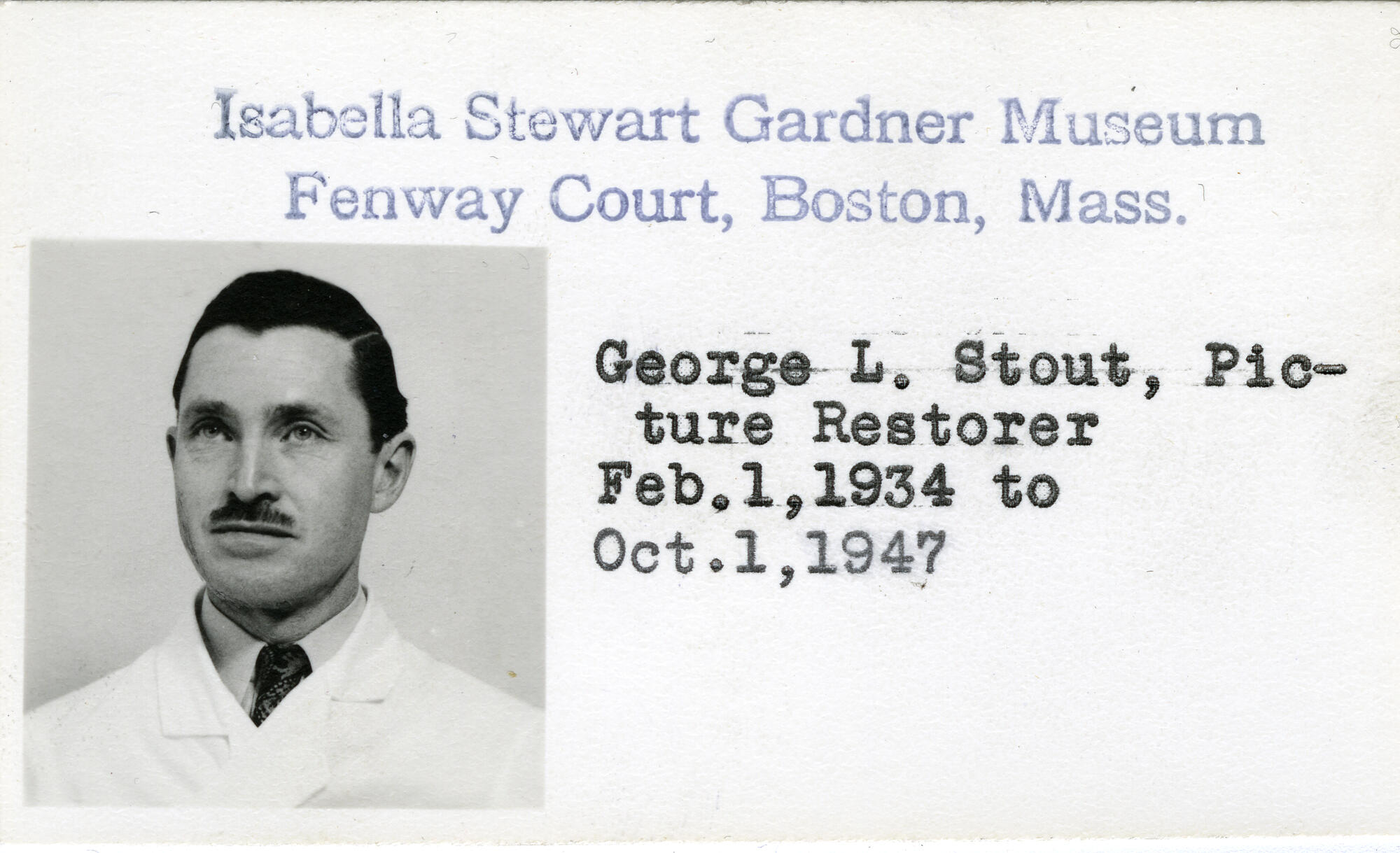

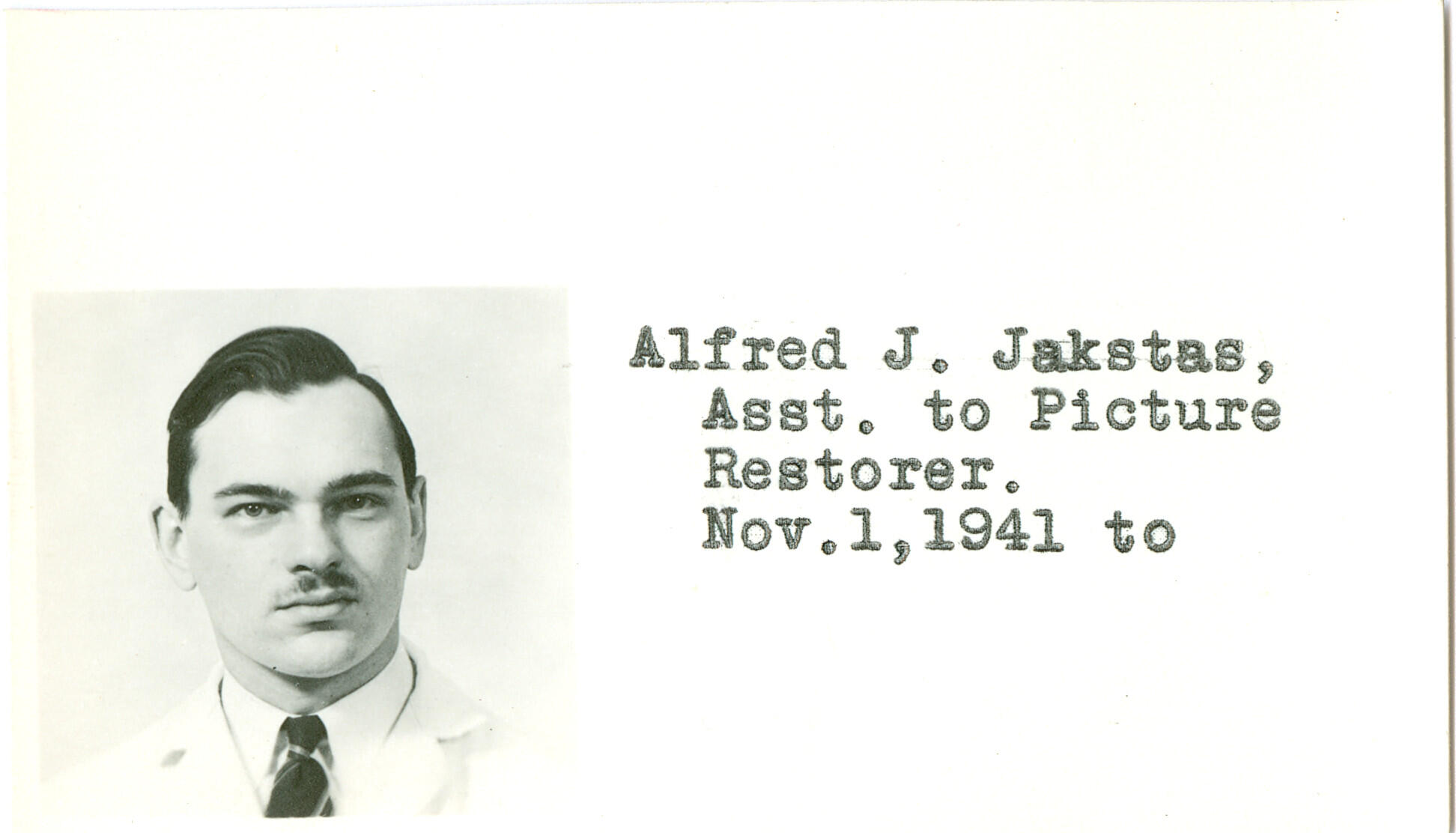

Carter worked closely with Gardner conservators George Stout and Alfred J. Jakstas to outfit the garage with appropriate storage racks, climate control, and security measures (including a great dane dog!) to ensure the art would be safe for however long it might need to remain hidden. The Danes were sworn to secrecy and only a select few people at the Museum knew the exact location of the repository.

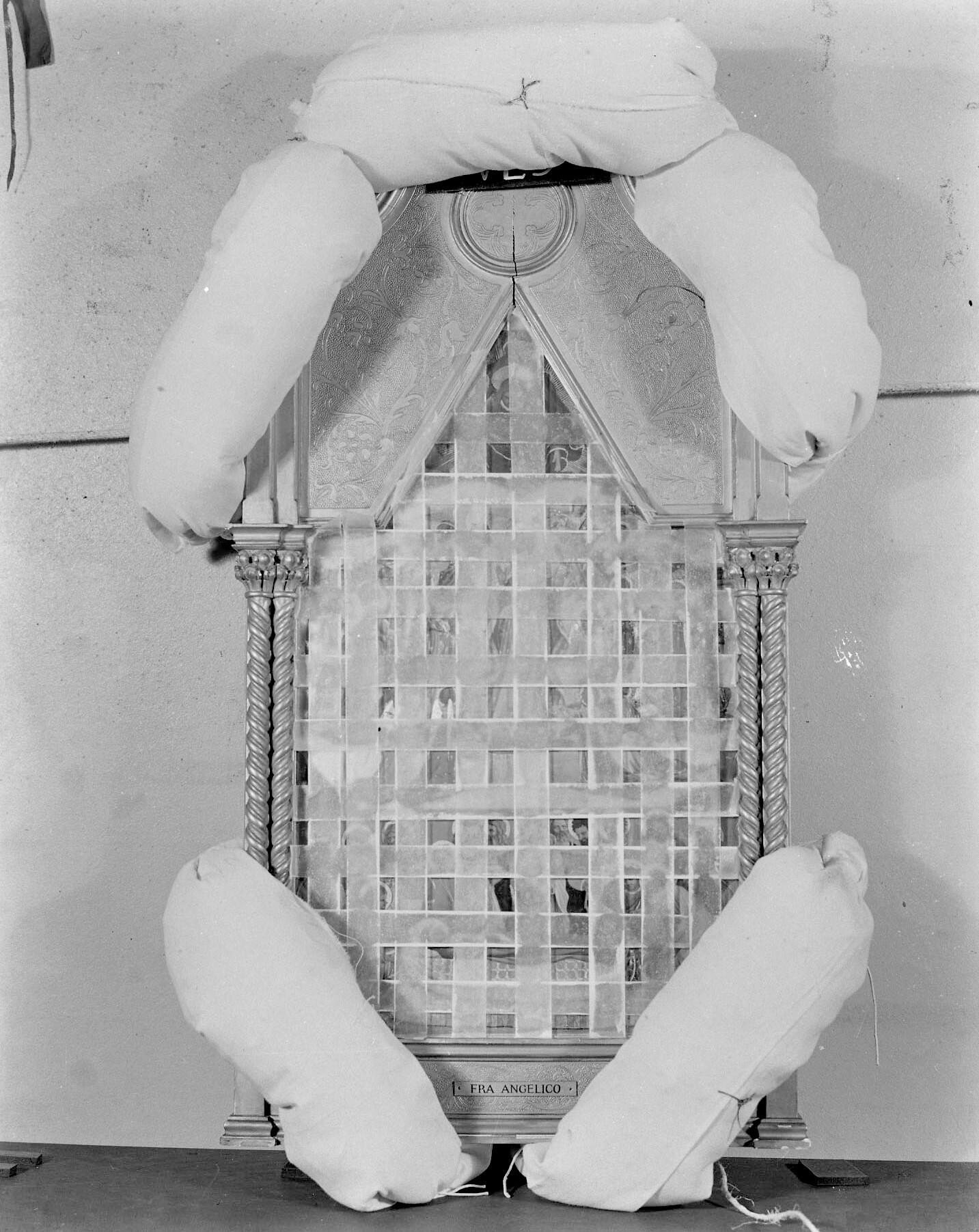

On March 2, 1942, ninety-five paintings and nine stained glass works were discreetly sent to New Hampshire. This included Titian's Rape of Europa, Vermeer's Concert, multiple Rembrandts, Botticellis, and the largest of all, John Singer Sargent's El Jaleo. The artworks were packed under the supervision of Stout and transported by truck, accompanied by two armed detectives from the William J. Burns International Detective Agency. Smaller objects such as silver, glass, books, and ceramics were stored onsite in the Museum's basement.

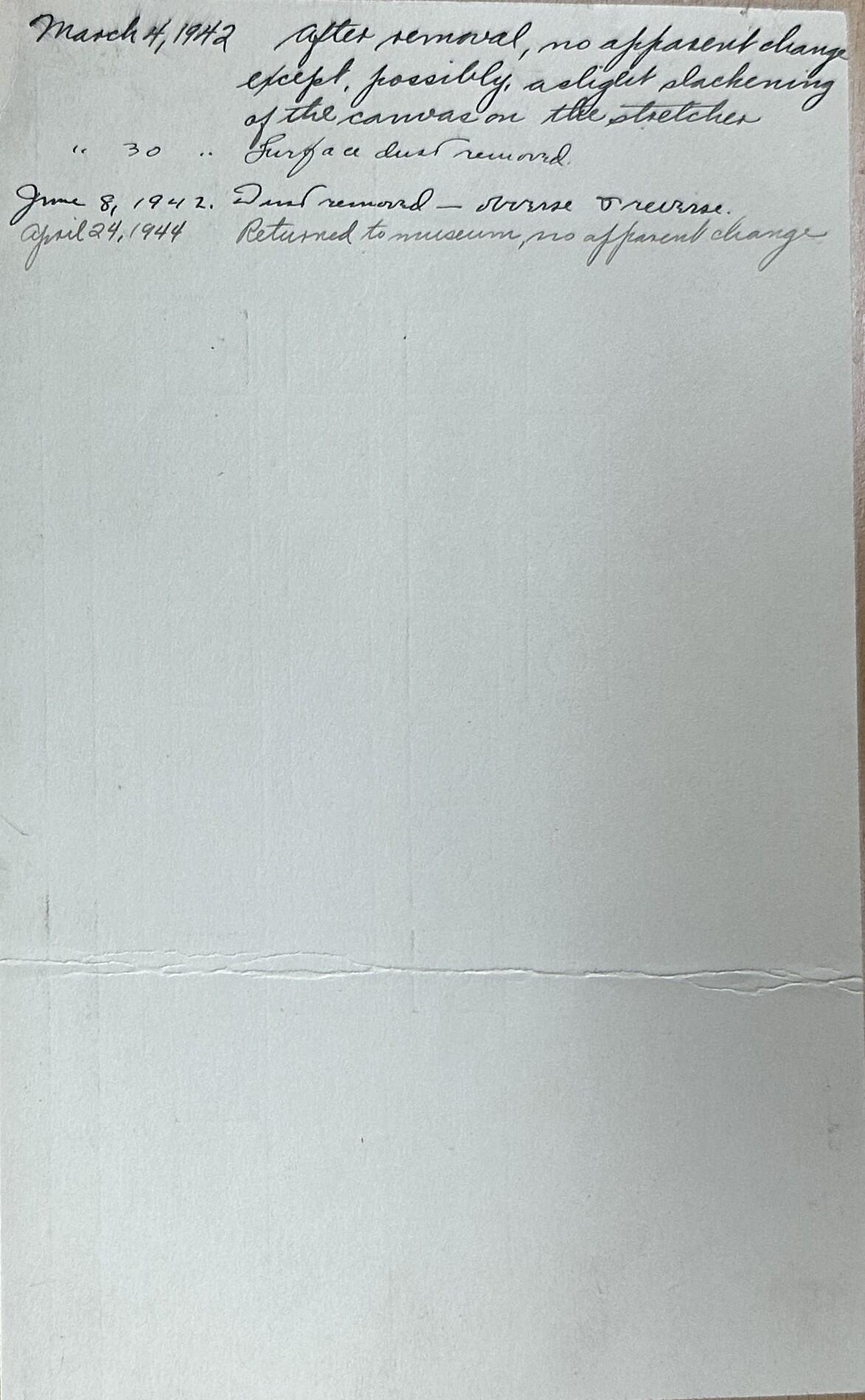

Each evacuated artwork received an evacuation card to document its condition, which could be compared with subsequent examinations during and after their time in storage to see if any damage or deterioration had occurred.

The Show Goes On

Despite the empty walls, the Museum remained open to the public. Visitors could still enjoy the building's architecture, furniture, the Courtyard's flowers, and musical performances. In the Museum's 1944 annual report, Morris Carter documented that despite the ebb and flow of visitor attendance over the preceding years, music seemed to be the chief lure.1 To fill the empty spaces in the galleries, the Museum's photographer, Joseph Brenton Pratt created life-size black and white photographs of the missing paintings to be hung in their place.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC2014.2.1)

Joseph Brenton Pratt (American, 1908–1998), Photograph of Johannes Vermeer's The Concert, 1941. Gelatin silver print, 72.5 x 64.7 cm (28 9/16 x 25 1/2 in.)

The artworks' stay with the Danes in New Hampshire was relatively short. In 1943, the Museum's trustees decided that everything could return to the Museum, a process that concluded in the spring of 1944.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

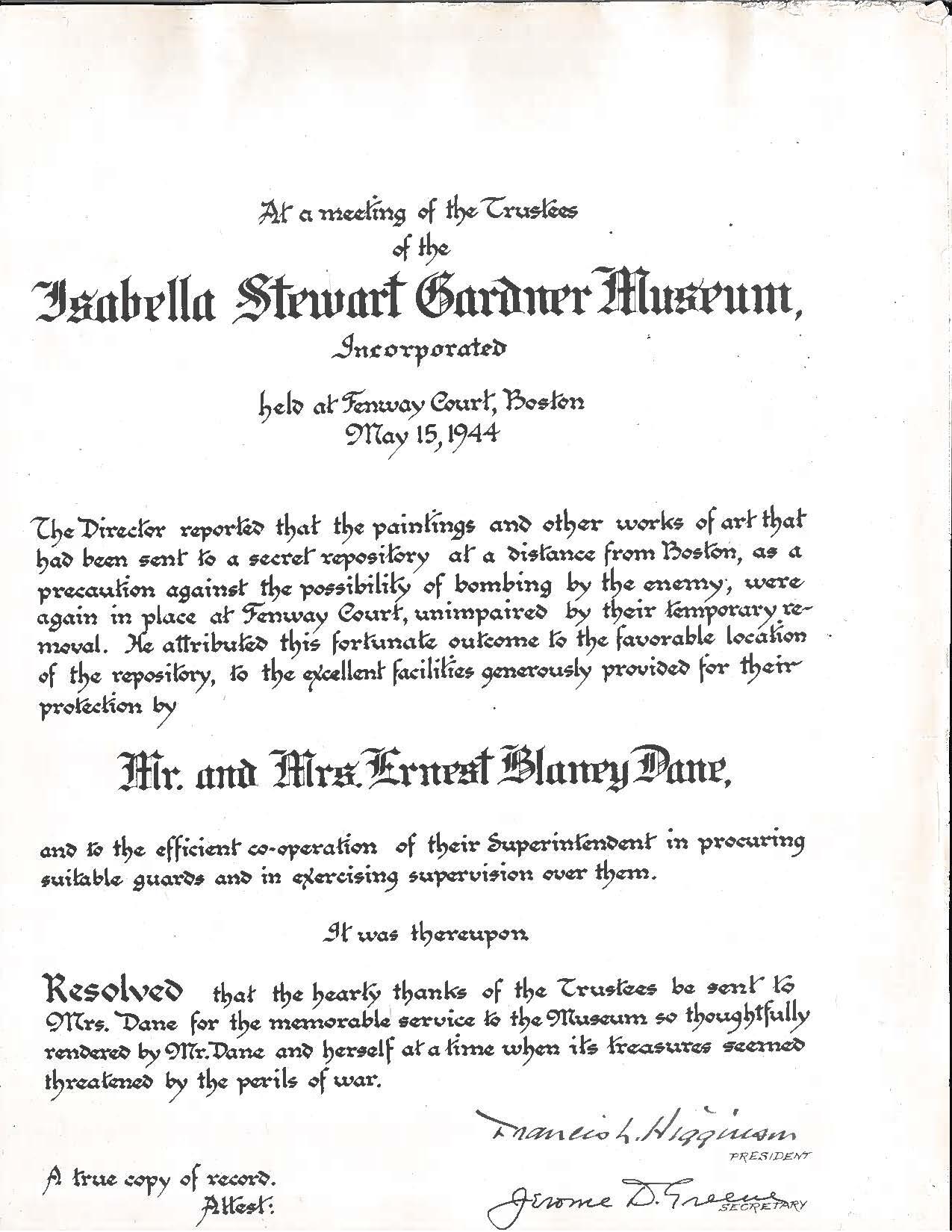

Copy of a certificate issued to Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Blaney Dane to commemorate their cooperation in the safeguarding of the Museum's collection during WWII.

A Lasting Legacy

As early as 1942, George Stout was petitioning the American government to take action against the damage being done to the art and buildings of Europe, stating:

To safeguard these things will show respect for the beliefs and customs of all men and will bear witness that these things belong not only to a particular people but also to the heritage of mankind.

Stout officially joined the war effort in 1943, leading the Monuments, Fine Art and Archives program (MFAA), more popularly known as the Monuments Men and Women, to recover and protect artwork and architecture throughout Europe. The preparations he was involved in at the Gardner acted as basic training for this monumental task. In 1955, he became the second director of the Gardner Museum.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

View of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1946.

Although calamity ultimately did not befall the U.S., the story of the Gardner's efforts to protect its collection is a testament to the dedication of those who work to preserve art and culture during times of global conflict. They refused to close the doors despite threats from abroad, ensuring the Museum remained a place of sanctuary and solace when the public needed it most.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Forever is a Long Time

Explore the Museum

Music at the Gardner

Read More on the Blog

Preserving our Colorful History: The Soisson Window

Notes

1Morris Carter, The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Incorporated, Twentieth Annual Report (Boston, 1944), p. 25.