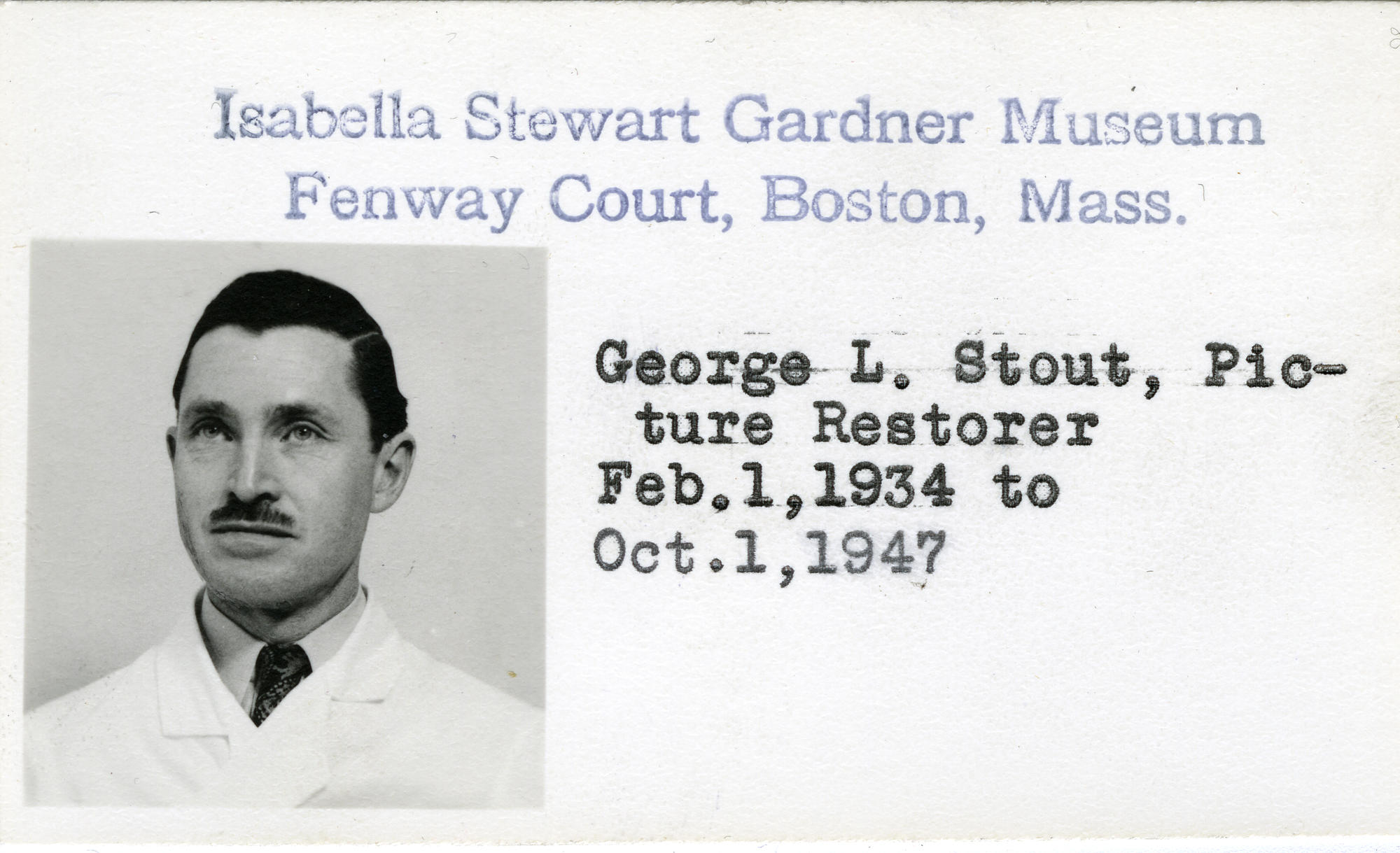

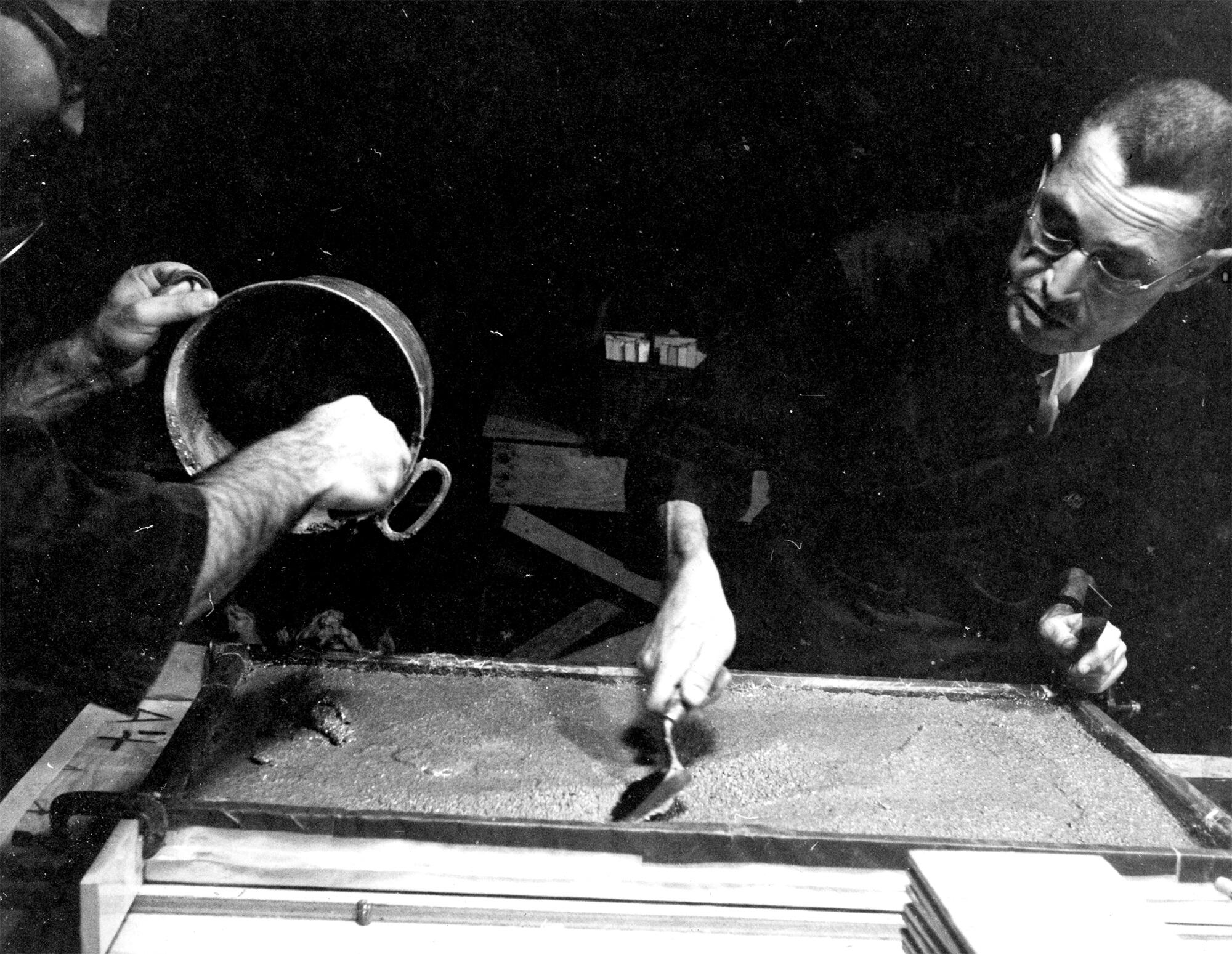

George Leslie Stout was born in 1897 and grew to be a man of many skills. In addition to being a painter, teacher, and avid traveler (much like Isabella Stewart Gardner herself), Stout was also a pioneer in uniting science and the arts. As a World War I veteran and Navy reservist, he returned to active duty at the start of World War II, where he worked to recover art and artifacts stolen by Nazis from hiding places like salt mines and churches. Stout performed these missions under a newly-formed unit called the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section, also known as the “Monuments Men.” Settling in Cambridge in the twenties, he obtained a master’s degree at Harvard, and in 1955, he accepted the post as the Gardner Museum’s second director.