“Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,” begins “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882), published in the January 1861 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, one of the leading literary magazines of the time. Americans (not just children!) listened and heard, making “Paul Revere’s Ride” one of Longfellow’s most frequently cited poems.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f508-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

John Steeple Davis (American, 1844–1917), Paul Revere's Ride, 1900. Photogravure

Isabella Stewart Gardner must have been delighted when, on November 12, 1902, Charles Eliot Norton (1827–1908), Professor of Fine Arts at Harvard University and a friend of the poet, offered her what he claimed was “the original ms.” of Longfellow’s poem, along with three other manuscripts, by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Felicia Hemans, and James Russell Lowell. She paid $1,500 for the lot (about $55,000 today) and displayed Longfellow’s poem in the Crawford / Chapman Case in the Museum’s Blue Room.

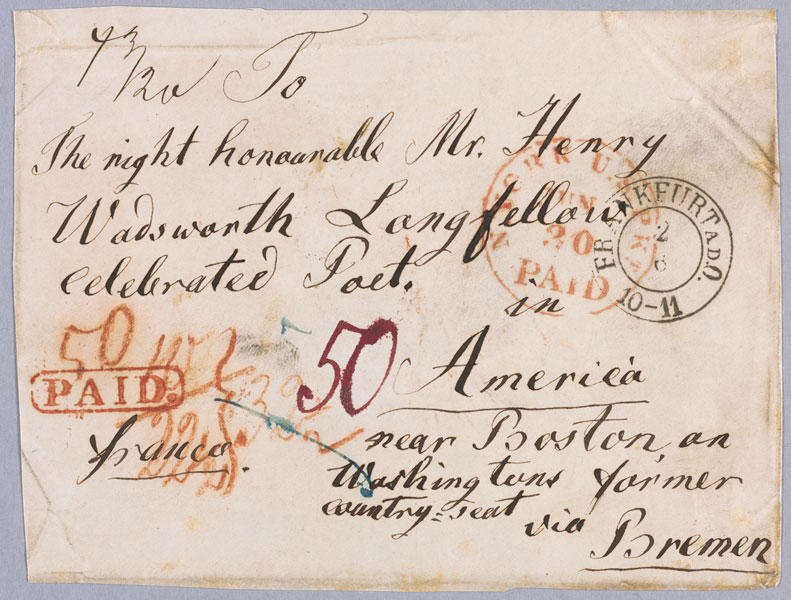

As it turns out, that was money well spent. Longfellow, likely the only poet in history to be able to quit a professorship at Harvard because he was making more money writing poems, became so famous that letters addressed to “Mr. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Celebrated Poet, in America, near Boston” would reach him without any problem. But his success was hard-earned, the result of painstaking craftsmanship. The Gardner manuscript sheds light on the hard work he put into his poetry.

Houghton Library, Harvard University. Longfellow Papers MS Am 1340 (198)

Envelope addressed "To the right honourable Mr. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow celebrated Poet,” from a scrapbook, 1842

Written on the eve of the Civil War, at a time when the (so imperfectly united) United States were falling apart over the issue of slavery, Longfellow’s poem hit a nerve. His recreation of the story of the Boston silversmith who, on April 18, 1775, rode through the night to warn the militia in Concord of the arrival of the British troops served as a reminder of the promise on which the country was founded. Longfellow’s editor James T. Fields, realizing the poem’s potential, arranged for it to run on the front page of the Boston Evening Transcript on December 18, 1860, two days before the new issue of The Atlantic Monthly hit the bookstores. A steady stream of reprints in other newspapers followed. By November 1863, when Longfellow inserted the poem’s final version into his collection Tales of a Wayside Inn, American readers would have been well familiar with it.

Library of Congress, John Davis Batchelder Collection

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882, author) and Ticknor and Fields (1854–1868, publisher), Tales of a Wayside Inn, frontispiece, 1863

Not everyone was a fan, however. Longfellow’s seeming disregard for historical fact—Revere never even reached Concord—has irked many readers. But Longfellow’s poem isn’t a history lesson. If anything, it’s a lesson about history, about what history feels like, what it sounds like. In a poem set almost entirely in the dark, we hear everything, from the “tramp of the feet” of the British in Charlestown to “the hurry of hooves” as Revere’s horse speeds away to the rooster that crows in Medford. Longfellow didn’t know what audiobooks were—but if they had existed in his time, he would have loved them.

Courtesy National Park Service, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Poems and Prose, in the H.W.L. Dana Papers (LONG 17314)

Illustration of “Paul Revere's Ride,” 1923–1949

The poem’s conclusion asks everyone to perk up and listen, and it’s easy to imagine what Longfellow’s readers, agonizing over slavery, would have heard in those lines:

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

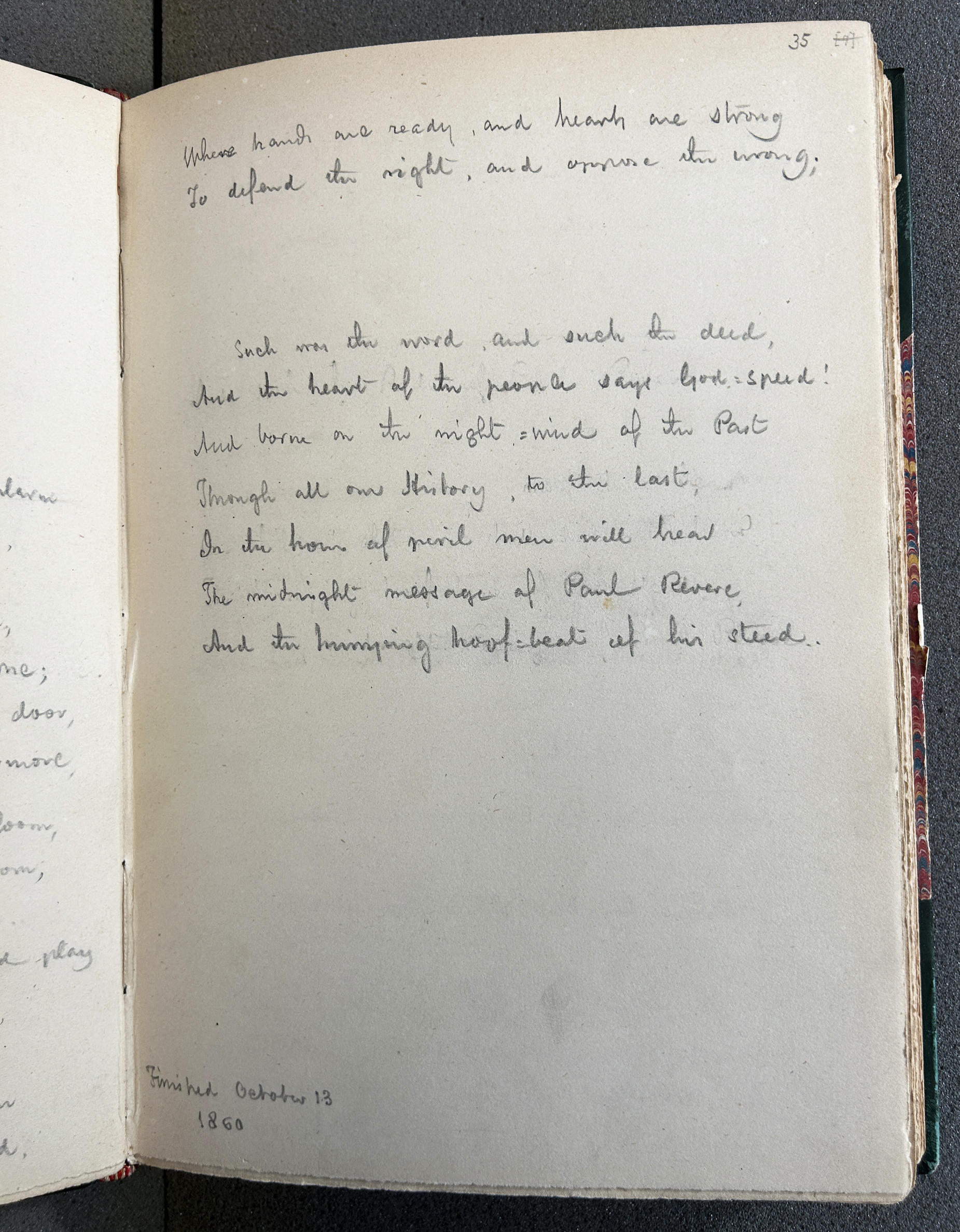

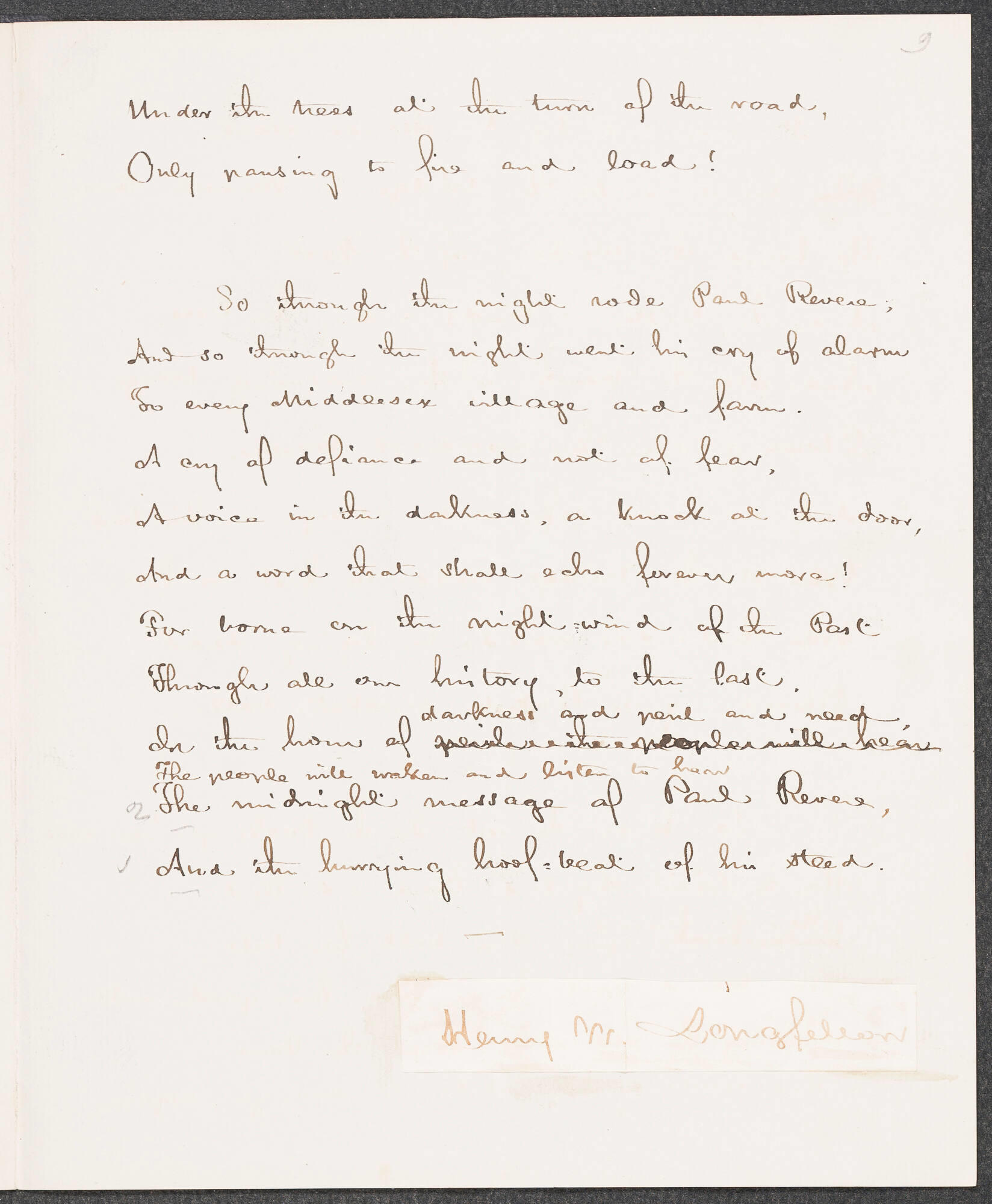

But these lines didn’t just materialize out of thin air. They were the product of endless revision. Norton told Gardner that he was selling her the poem’s original manuscript, but that was only somewhat true. The very first draft of “Paul Revere’s Ride,” written in pencil, is now at Harvard’s Houghton Library. But (as hasn’t been clear until now) the manuscript purchased by Gardner was used for the printings in the Boston Evening Transcript and The Atlantic Monthly. Here is the ending of the poem in the Gardner manuscript as Longfellow had first copied it from his pencil draft, substituting “people” for “men”:

In the hour of peril the people will hear

The midnight message of Paul Revere,

And the hurrying hoof-beat of his steed.

But then he really got going, crossing out several words and adding an entirely new line:

In the hour of peril the people will hear darkness and peril and need,

[The people will waken and listen to hear]

The midnight message of Paul Revere,

And the hurrying hoof=beat of his steed.

Longfellow’s revision piles up the emergencies (“darkness and peril and need”), thus making Revere’s message seem more urgent. At the same time, the line he inserts (“The people will waken and listen to hear”) creates a pleasant sense of completion, referring the reader back to the poem’s beginning.

But something was still awry and editor Fields knew precisely what. In a letter to Longfellow of November 13, 1860, he proposed reversing the last two lines. And lo and behold, Fields’s faint pencil marks appear next to the last two lines in Gardner’s manuscript—a “1” next to the penultimate line and a “2” next to the last. Fields’s intervention changes the rhyme scheme, but the poem now ends, with a flourish, on the word “Revere”:

In the hour of darkness and peril and need

The people will waken and listen to hear

2 And the hurrying hoof=beat of his steed,

1 The midnight message of Paul Revere.

The poem’s final version in 1863 amends “hoof-beat” to the more realistic-sounding plural “hoof-beats,” and “his steed” becomes “that steed,” creating a subtly alliterative echo with “beat” and enhancing the internal near-rhyme “beat / steed.” But everything else remains the same.

These are not the only improvements in Gardner’s manuscript. My favorite among them involves the description, earlier in the poem, of the rickety ladder Revere’s friend uses to hang his lanterns—warning signals for Revere who’s waiting on the opposite shore—in the belfry of the Old North Church. In the pencil draft, Revere’s friend is climbing “Up the light ladder, slim and tall,” which Longfellow, in the Gardner manuscript, changes to “Up the light ladder, slender and tall.” The additional syllable in “slender” makes the line wobble a bit. In the 1863 version, Longfellow achieved perfection. Here the friend goes up “By the trembling ladder, steep and tall”: it’s not only the ladder that’s shaking here but also Revere’s friend!

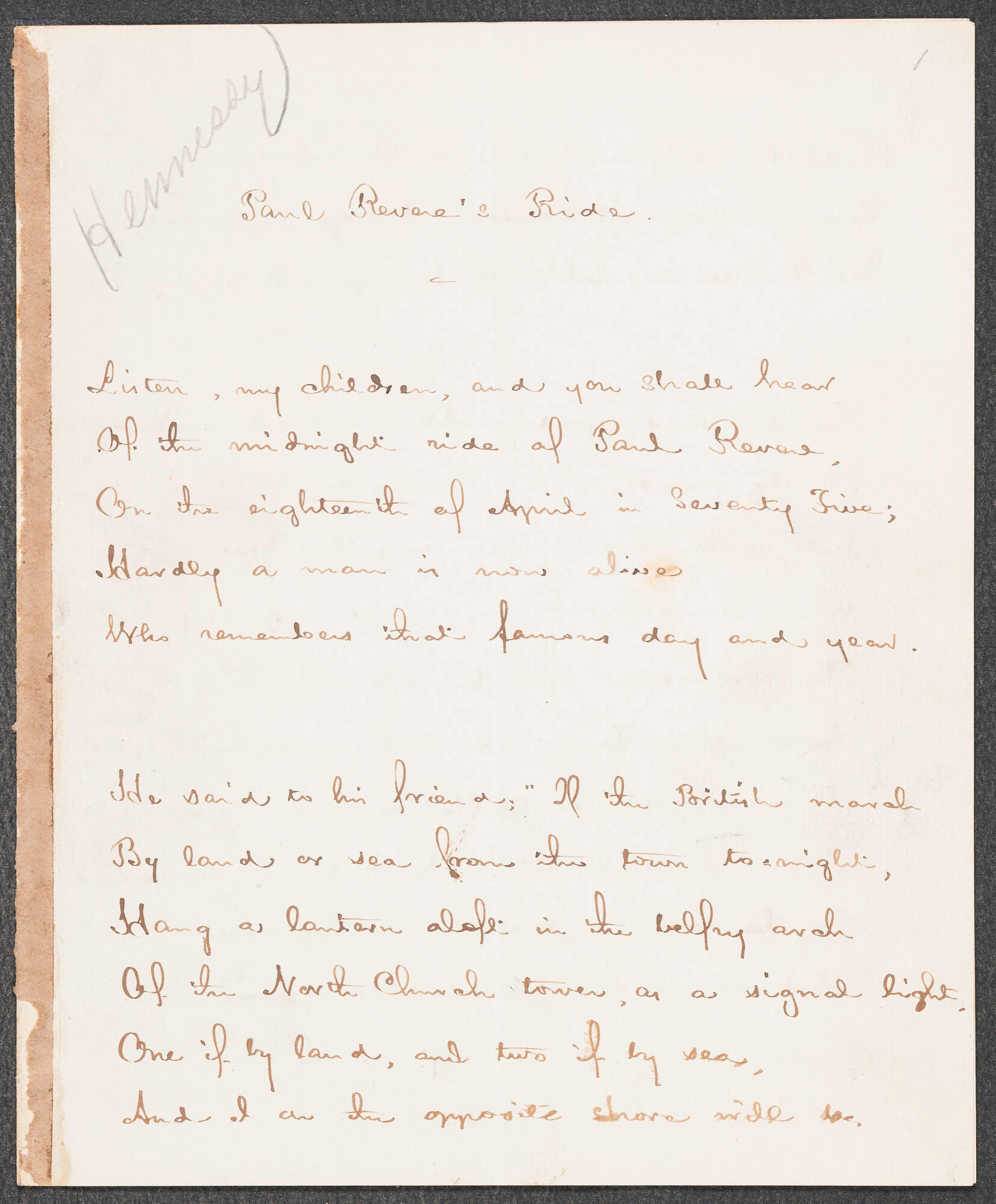

One final clue confirms the role that Gardner’s manuscript played between the original pencil draft and the final print version. Written diagonally across the top of the first page of Gardner’s manuscript appears the name “Hennessy”—a reference to the poem’s “compositor,”: the person who typeset Longfellow’s poem for The Atlantic Monthly. Hennessy’s name can also be found on other Atlantic submissions, such as James Russell Lowell’s poem published in August 1858.

Incidentally, a “James Hennessy, compositor,” Irish-born and fifty-two years of age, is listed in the United States Federal Census of 1880 as living at 8 Gay Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with his wife and six daughters. If this is indeed the same Hennessy, he would have been thirty-one when he worked on Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride.” If Mr. Hennessy’s traces have mostly vanished in the sands of time, Gardner’s manuscript preserves his part in making “Paul Revere’s Ride” available to so many generations of readers or—to stay within the image Longfellow would have preferred—listeners.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

The Story Behind Porsha Olayiwolas Poetry

Explore the Museum

The Fifteen Cases

Watch a Short Video

Isabella as Book Collector and Reader