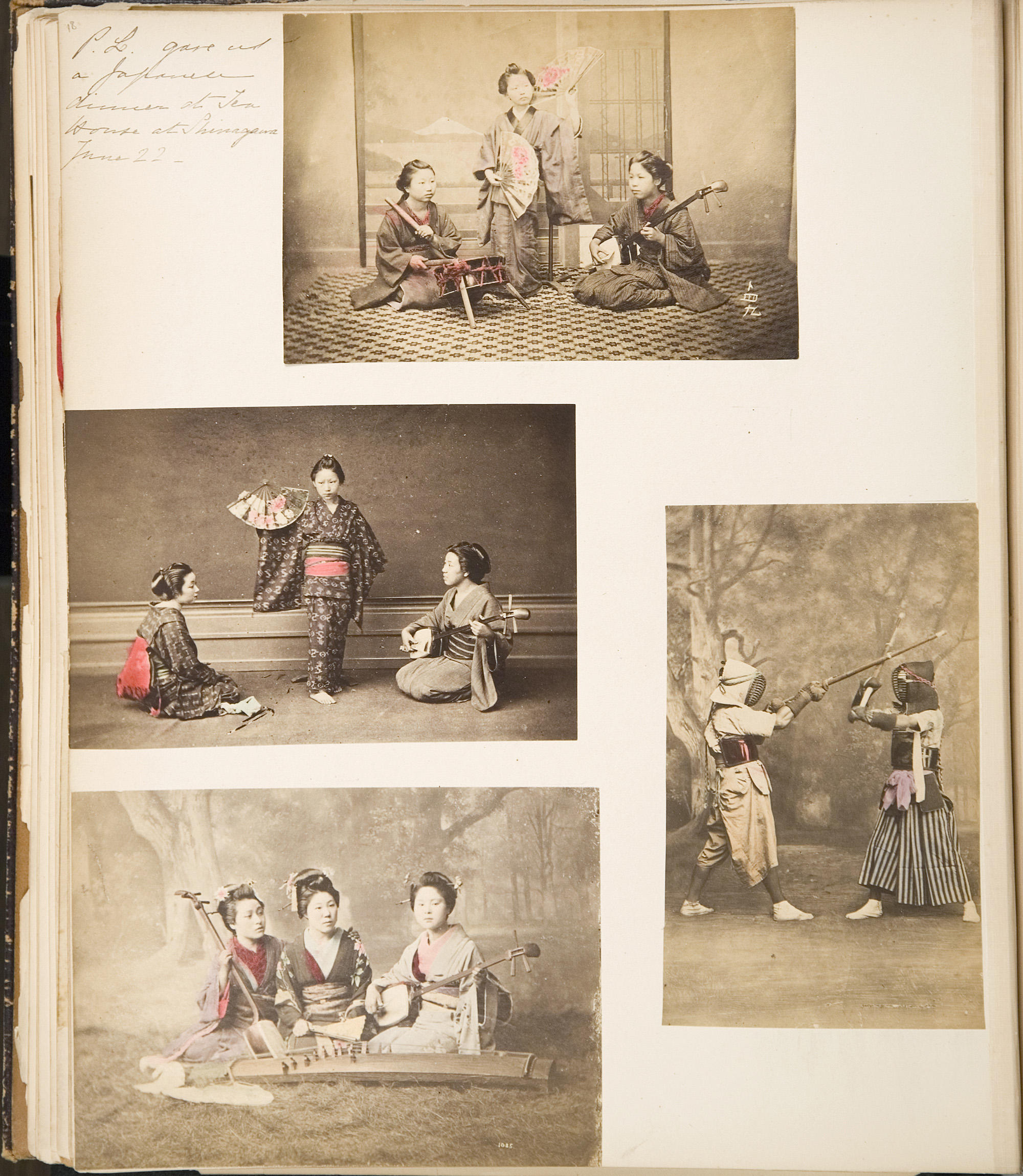

On May 31, 1883, the Gardners boarded a steamer in San Francisco bound for a tour of Asia that would last more than a year. Their itinerary included China, Vietnam, Cambodia and India among other countries, but their first stop was Japan, where they spent three months traveling to different parts of the country. As they explored, Isabella kept travel albums and journals detailing their journey.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840-1924), Travel Album: Japan, 1883, page 19

Isabella would not become a serious art collector until almost a decade after her trip to Asia; however, when the Gardners returned home, they learned they had inherited the Green Hill estate in Brookline, Massachusetts as both of Jack’s parents had died during their year of travels abroad. In addition to displaying a pair of Japanese screens bought on their trip, Isabella also created a Japanese garden at Green Hill, which was certainly inspired by gardens she had visited while traveling in China and Japan.

Photo: Thomas E. Marr & Son (active Boston, about 1875-1954)

Isabella’s Japanese garden at Green Hill, 1901

In 1904, a year after her museum had opened, Isabella was introduced to Okakura Kakuzō, a Japanese scholar of art and culture, through their mutual friend, John La Farge. Okakura had come to Boston to advise the Museum of Fine Arts on their Asian art collections, and would later become their curator of Asian art. Okakura and Gardner forged a deep friendship based on a mutual appreciation of Japanese art and Okakura instructed Gardner in the arts of Asia including the Japanese tea ceremony. He would later give Gardner his own tea set and a copy of his essay, The Book of Tea.

Okakura Kakuzō, about 1903

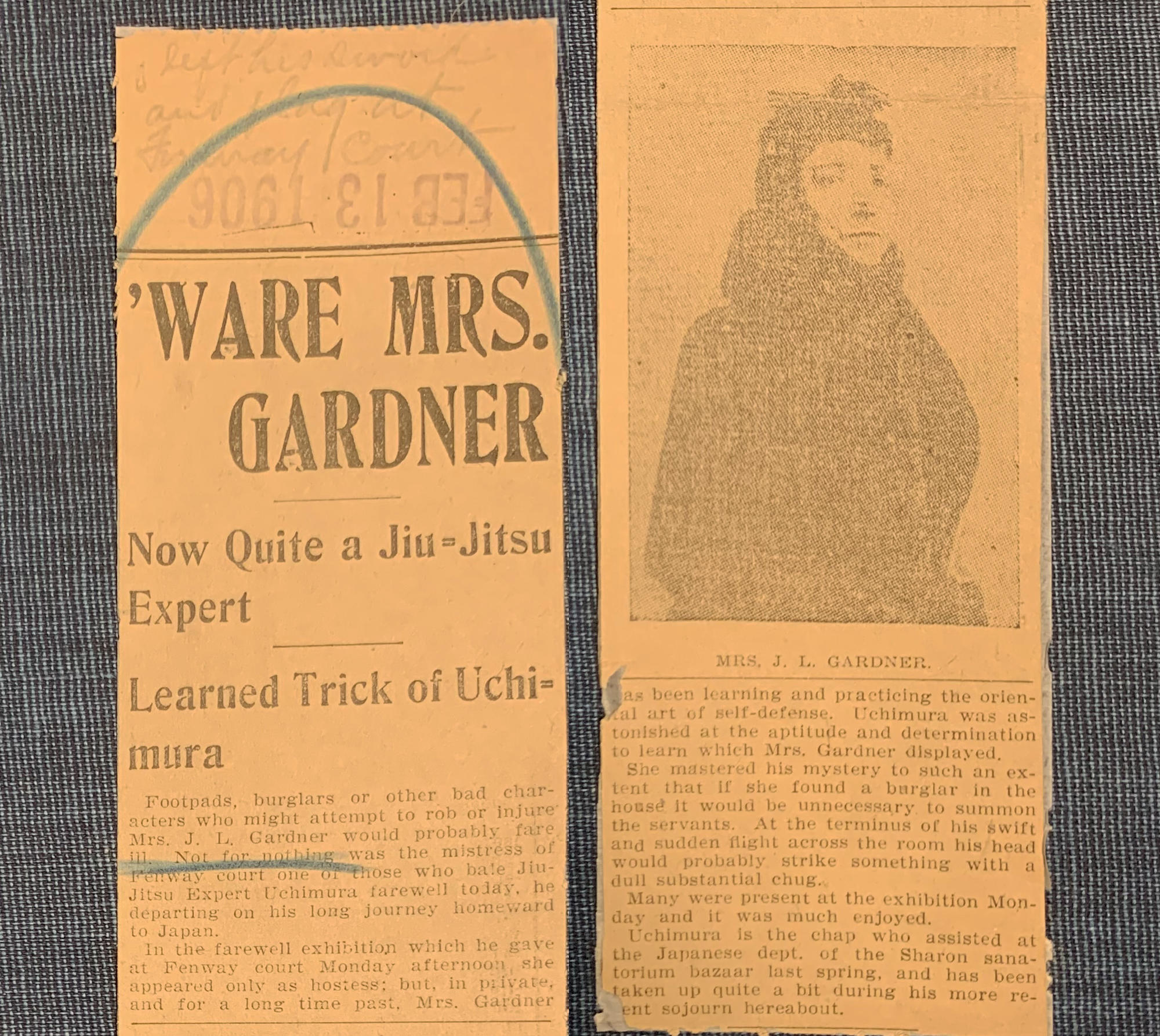

Okakura also introduced Gardner and her circle to other Japanese associates, including an expert in Jiu Jitsu named Uchimura Tengan. Soon Isabella started learning the martial art and newspapers couldn’t resist reporting on her lessons. One article even warned burglars and bad characters to beware of Isabella’s new skills.

“‘Ware Mrs. Gardner—Now Quite a Jiu-Jitsu Expert—Learned Trick of Uchimura,” Newspaper clipping, 13 February 1906

Perhaps in recognition of her interest, Uchimura gifted Gardner an early 19th-century Japanese katana Sword and Scabbard.

Kinai Nanadai (Japanese, active Echizen, 19th century), Sword and Scabbard, early 19th century, before 2019 treatment

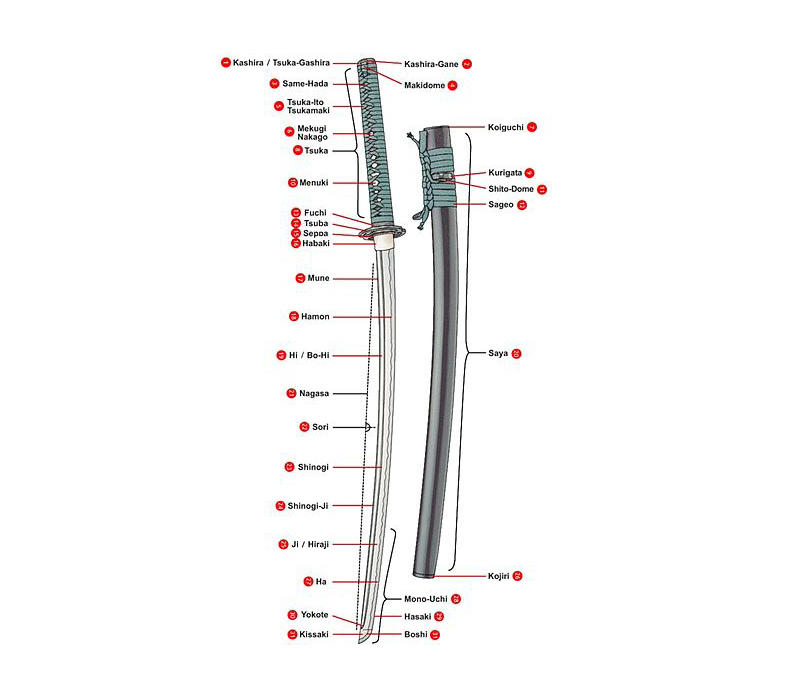

The sword has a long, curved steel blade that may have taken days or even weeks to craft, according to traditional techniques of Japanese blade-forging. The fabrication of Japanese katanas are intricate and each component has its own precise name.

Courtesy of Wikipedia under a GNU Free Documentation License

A diagram of a katana and koshirae with components identified

Like most katanas, the wooden hilt of Gardner’s sword is covered with stingray skin, which is both decorative and has a bumpy texture that may have provided additional grip. The hilt is also wrapped with a dark blue silk cord in a decorative pattern that exposes diamond-shaped patches of the white stingray skin underneath. Unfortunately, at some point in the sword’s past, the hilt broke and the top four inches snapped off just above the end of the steel tang.

Kinai Nanadai (Japanese, active Echizen, 19th century), Sword and Scabbard, early 19th century, before 2019 treatment, detail of the broken hilt

When the hilt broke, a piece of the blue silk cord also went with it, while another section of the blue silk cord appeared to be missing.

Luckily, the broken section of the hilt fit back together well and the splintered wooden core provided plenty of surface area for gluing the pieces back together. When the object was brought into our Conservation Lab, we were able to reattach the hilt section with fish glue and then wrap the joint tightly with stretch wrap, which provided even pressure all around the repair while the glue dried.

Kinai Nanadai (Japanese, active Echizen, 19th century), Sword and Scabbard, early 19th century, during 2019 treatment, detail of the hilt repair

With the hilt firmly reattached, we were able to clean the dirty stingray skin with tiny cotton swabs and deionized water. Notice how much cleaner and brighter the diamonds on the left side are compared with the right!

Kinai Nanadai (Japanese, active Echizen, 19th century), Sword and Scabbard, early 19th century, during 2019 treatment, detail of the stingray skin

The next step was to reposition the existing blue silk cord and use thin entomological pins to hold the existing blue cord in the proper position. We reattached the separated cord piece using Japanese tissue paper made from kozo fibers that was painted blue to match, and adhered it in place with a small amount of an acrylic resin adhesive, which retains its flexibility when dry.

Although the scabbard was in good shape, its white silk cord was frayed and missing about half of its original length. We decided to get a new white silk cord of the proper length from Japan so that it could be properly tied in a traditional knot. We put the original cord into storage where it can be accessed by future researchers.

Kinai Nanadai (Japanese, active Echizen, 19th century), Sword and Scabbard, early 19th century, during 2019 treatment, detail of the scabbard knot

The newly conserved Sword and Scabbard are back on view and can be admired in its original place in the Vatichino gallery. The Vatichino is a space where Gardner kept personal souvenirs, mementos and gifts commemorating her travels and friendships. What a perfect place to reflect on her early trip to Asia and the friendships that blossomed at home!

Kinai Nanadai (Japanese, active Echizen, 19th century), Sword and Scabbard, early 19th century, after 2019 treatment

You Might Also Like

Read More on Inside the Collection

Travel through China with Isabella in this blog post

Explore the Collection

Okakura Kakuzō (Japanese, 1862–1913), Letter to Isabella Stewart Gardner from 253 Marlborough Street, Boston, 12 February 1906

Explore the Collection

Isabella Stewart Gardner (American, 1840-1924), Travel Album: Japan, 1883