Most Americans today associate Labor Day with a three-day long weekend that marks the unofficial end of summer before children go back to school. However, Labor Day was established to celebrate the social and economic achievements of American craft workers, artisans, tradesmen, and laborers. The holiday is rooted in the plight of American workers who advocated, and often fought for, workers’ rights that ensured safety, dignity, and fair wages. Americans honor the fruits of this effort by celebrating leisure and togetherness. The spirit of this tradition shapes how we celebrate this holiday today.

The history leading up to the incarnation of the holiday started when the labor movement began to influence policy. By the mid to late 1800s, workers organized and used strikes to ensure protections, rights, and wage increases–and they refused to work until their demands were met. By 1887, states such as Massachusetts made Labor Day a state holiday, officially recognizing tradesmen and laborers’ efforts in a post-Industrial Revolution society.

Federal status didn’t become a reality until the Pullman strike in 1894. Railroad union members brought most train service west of Detroit to a halt for several months, causing major disruption and upheaval nationwide. On June 28, 1894, in a move to mollify labor unions, President Grover Cleveland signed into law Labor Day as a federally observed holiday celebrated on the first Monday in September.

Labor Day parade on Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., 1894

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

In cities like Boston, labor unions celebrated the newly minted holiday with parades and picnics, which are the same types of festivities still seen today. But a national holiday did not stop organized workers from their effort to change policy. The people who labored to build Isabella Stewart Gardner’s museum–years after the holiday was federally established–are part of this history.

Building the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

After the death of her husband, Isabella purchased land in the Back Bay Fens of Boston and broke ground in June 1899. Carpenters, bricklayers, stone masons, and others brought Isabella’s vision to fruition brick by brick, column by column. It was a labor-intensive job for many of the Italian and Irish immigrants who constructed the Museum, working long hours for little pay.

Architect Williard Sears also didn’t anticipate Isabella playing such an active role in overseeing much of the construction, oftentimes insisting the workers redo their work. This challenge, coupled with the shaky climate around union workers’ rights, was a recipe for contention.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (New York, 1840 - 1924, Boston), Fenway Court During Construction, 1900-1901. Gelatin silver print

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.009293).

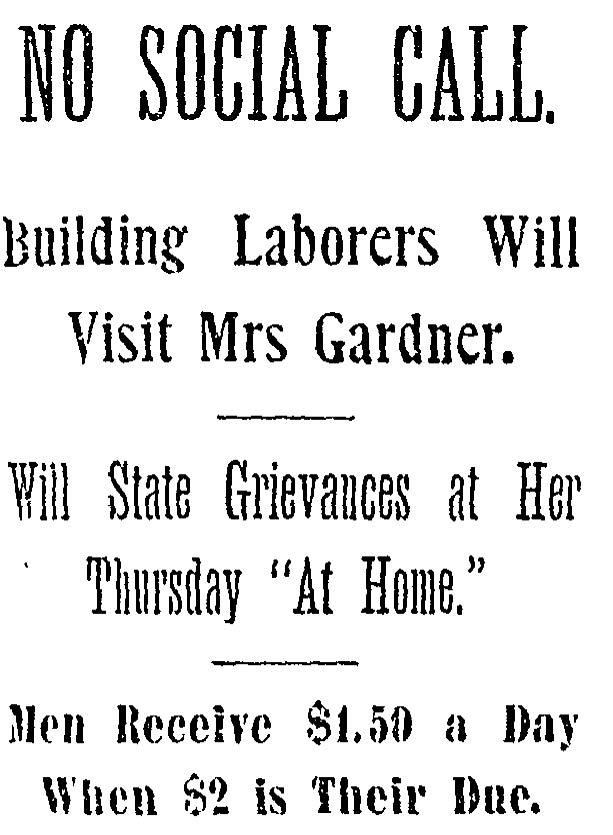

As the Palace was built, carpenters held twenty-one strikes across the state throughout the year 1900 alone. The Boston Daily Globe reported on May 13, 1901 that a delegation of building laborers were planning to state their grievances to Isabella “at home” on that upcoming Thursday. Their chief complaint being they only received $1.50 per day when they should be receiving $2. They alleged that the difference of 50 cents was going “into the pocket of a middleman.” It is not clear if they staged such a protest at Isabella’s home, but it was reported that Isabella would not meet with them. According to a letter from her attorney to the union’s business agent, “she has nothing whatever to do with employing the workmen or paying, and has no right or inclination to interfere with the matter in any way whatever.”

Article headline from Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), May 13, 1901, pg. 1

ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe

Almost two years after construction began, on July 2, 1901, the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners and the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters declared a strike to demand that carpenters who worked in Boston, Brookline, and Cambridge get an eight-hour workday at $2.70 a day. A newspaper reported that workers walked off of Isabella’s job site when their demand for wages and a shorter work day was not met, impacting the construction of Isabella’s museum.

The strike affects the Back Bay palace of Mrs. Jack Gardner, which has been the scene of so many labor disputes during the last season. The carpenters employed presented their demands, but the contractors refused to grant the shorter work day and the men promptly walked out.

Records state that Isabella was “considerably annoyed” by this disruption, but we don’t know her true sentiments toward the labor groups and their cause, or if the men actually succeeded in getting the compensation they demanded. Despite the turmoil and union workers’ strikes, construction continued as planned.

The Palace, A Labor of Love

Not all the men working on Isabella’s museum were disgruntled, in fact, many executed the project with dexterous enthusiasm. One skilled laborer, Teobaldo “Bolgi” Travi, was so passionate and meticulous with the luxurious materials that Isabella appointed him as a supervisor. He eventually became the Museum’s first caretaker and protector. The first director at the museum, Morris Carter, expressed that Bolgi fiercely protected Isabella’s collection and took care of the building with “affectionate supervision.” Bolgi’s personal story echoes the same passion and vigor that Isabella had in her vision.

To this day, we continue to learn more about the history of the people involved in the building of the Museum’s great structure. We recently came to learn about another construction worker named Generoso Cataldo, thanks to a recent visit by his descendants. According to his grandson, Cataldo was between 22 and 25 years old when he worked on the Museum construction site—a single man probably renting a room somewhere nearby and happy for the steady work. His grandson and great granddaughter visited the Gardner and generously shared their connection to the Museum’s history. The man on the far right in this photograph taken by Isabella is perceived to be Cataldo. His part in the building of the Museum is now part of his family legacy.

Skilled workers like Bolgi and Cataldo involved in the construction of the Museum are an integral part of the history and culture of the city. They are just as important as the Gardner’s collection itself. Labor Day is just one way to celebrate the efforts and struggles of workers, immigrants, and talented laborers dedicated to the building of the Palace. Thanks to the many hardworking individuals, this labor of love–as Isabella intended–continues to awe and inspire for “the education and enjoyment of the public forever."

We are interested in telling more stories about people like Bolgi and Cataldo who helped to build and maintain the Museum. Please email archives@isgm.org if you have any stories or documents related to people who have worked at the Museum over the years.

You May Also Like

Building Isabella’s Museum

Read More

New Meets Old

Read More

BOLGI: THE FIRST CARETAKER AND PROTECTOR OF THE ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM

Read More on the Blog