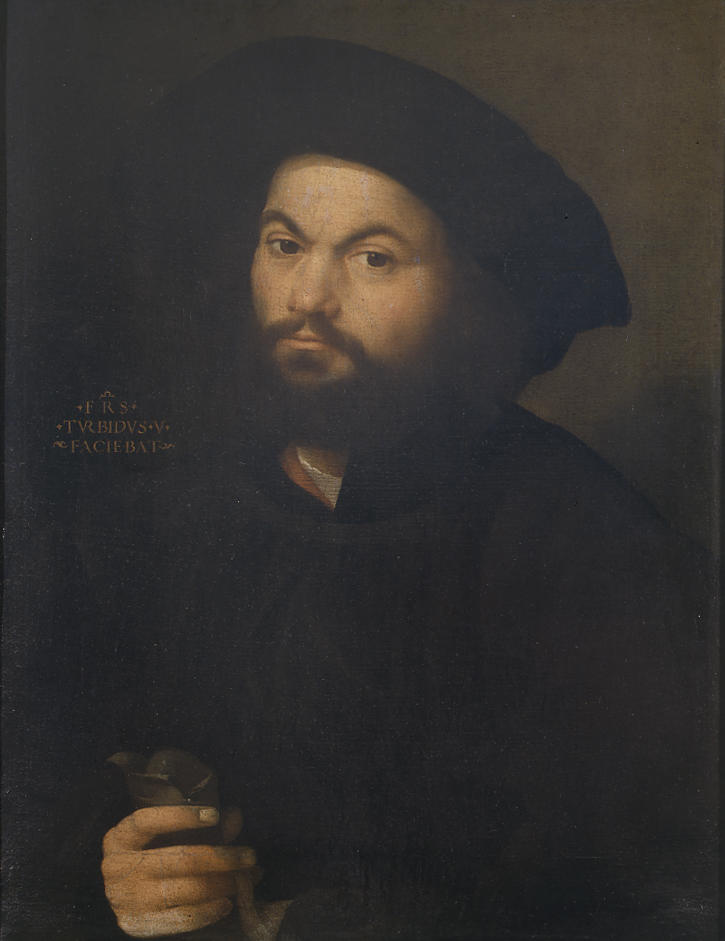

His name – Francesco Torbido, called Il Moro – tells us a lot more. In Italian, the word torbido means “cloudy.” Francesco also went by a nickname, “the moor.” Although the term technically describes North African Muslims in Spain and Italy during the Middle Ages, Renaissance Italians used this word colloquially to describe dark skin color, Black African heritage, or both (Moro was also the surname of a Venetian noble family, but Francesco was not among their members). Combining the words torbido and moro, we can deduce that Francesco was likely mixed race, the child of one white parent and one black parent. Where might his Black parent have originated? His father’s name was Marco di India or “Marco from India.” On Renaissance maps, “India” was often used to identify Ethiopia, although the term could also refer to sub-Saharan Africa more generally. Marco was sometimes even referred to as “Francesco d’India”.

Could this be him? Some people even speculate that this signed painting to be his self-portrait.