Isabella Stewart Gardner had a life-long love of Italy. But she was certainly not the only one to feel this way; many Bostonians traveled to Italy and were similarly interested in its art, history, and literature. Their visits were facilitated by Anglo-American communities in cities like Rome, Florence, and Venice. Hotels, rental apartments, restaurants, shops, and other institutions catered to the needs of these communities. This allowed travelers and residents alike to participate in a whirl of social activities encompassing teas, musical parties, and salons as well as visits to famous sites, artists’ studios, and attendance at the rituals of the Catholic Church, which these mostly Protestant travelers viewed with both fascination and skepticism.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P33n36). Isabella displayed this watercolor of Rome in the Vatichino.

Unidentified Italian painter, Rome, 1895. Watercolor on paper, 33.75 x 61.5 cm (13 5/16 x 24 3/16 in.)

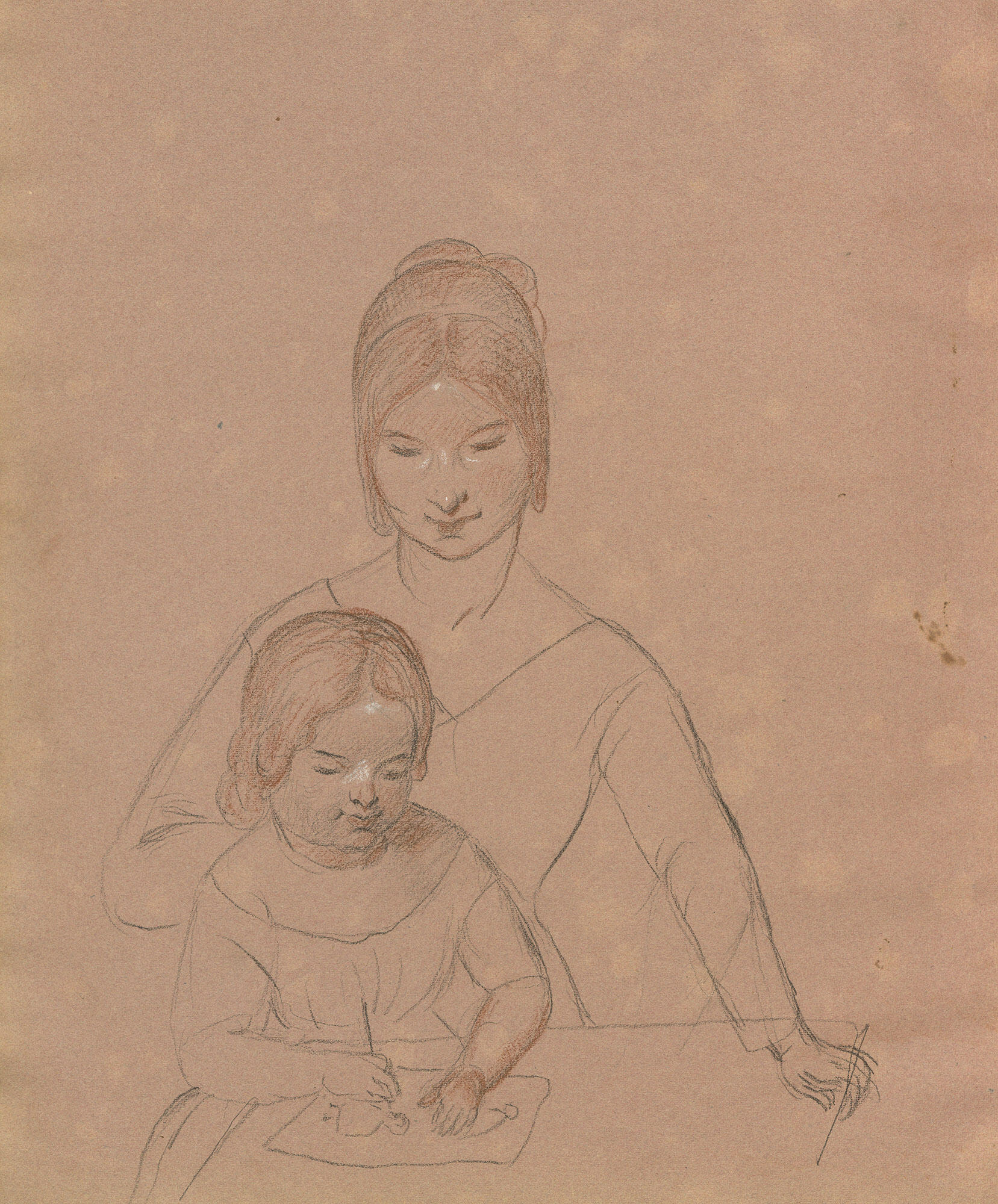

While most Bostonians stayed in Italy for a few weeks or months, some took up long-term residence, and these residents welcomed friends and friends of friends with open arms. For many travelers, a stop in Florence was not complete without a visit to the Alexander family. Francis Alexander had been a successful portrait painter in Boston; in 1836, he married Lucia Gray Swett, daughter of a prominent Salem family who made their fortune in shipping and their only child Esther Frances, then known as Fanny, was born the following year. Francis encouraged Fanny’s artistic ability from an early age, though she never had formal instruction; in one of his sketchbooks he captures her as a child, sitting with her mother drawing. The Alexanders led a life of privilege in Boston, and they befriended many of the most prominent members of society, including the Longfellows, Lowells, Shaws, and Whittiers. But Italy was a powerful draw for Francis and Lucia; he was studying art and she was traveling with her family when they first met there in 1832. So it is not surprising that they decided to move to Florence in 1853.

Wellesley College Special Collections

Francis Alexander (American, 1800–1880), Lucia and Fanny Alexander, folio from a sketchbook, 1840s. Crayon, 39 x 30 cm / 15 x 11.8 cm

Fanny, who adopted the Italianized Francesca, continued creating art in Florence. She focused on capturing portraits of the Anglo-Americans who lived in or passed through the city as well as the Italians her family befriended and details of the countryside around them. Some of their Italian friends were government officials, poets, and patriots engaged in the protracted battle for Italian independence. Others were agricultural workers, seamstresses, straw weavers, and the sick and downtrodden, many of whom became models for her art. Francesca was deeply charitable and sought to better their lives, so she devoted much of her time, as well as the money she earned from selling her art and other funds she solicited from wealthy friends, to assist them however she could.

Wellesley College Special Collections

Francesca Alexander (American, 1837–1917), Pig, 1850s. Pen and ink, diameter: 9.5cm (3.74 in.)

The Alexanders remained in close contact with many of their Boston friends, including the parents of Isabella’s husband Jack. The Gardner and Peabody families, like Lucia, were connected to Salem’s maritime trade, and Lucia’s letters to the couple share gossip about Bostonians in Florence and Francesca’s activities. In May 1863 she wrote, “Between the poor who are in want, and the rich who are invalids, with [Francesca’s] painting and her singing, she is one of the most laborious of the working classes.” Isabella’s in-laws arrived in Florence in 1864 and immediately commissioned Francesca for what would become her largest and most complex painting, a group of three girls—identifiable as local laborers, or contadine, by their costumes—leaving flowers at a roadside shrine to the Madonna and Child.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P17w29). See it in the Short Gallery.

Francesca Alexander (American, 1837–1917), Decorating a Shrine, 1865. Oil on canvas, 125.2 x 93 cm (49 5/16 x 36 5/8 in.)

Although Francesca’s correspondence and other sources indicate that she made a number of paintings, all representing contadine, Italian peasant girls or women, engaged in various activities, the Gardner painting is the most thoroughly documented. Francesca wrote to her friend Lilly Cleveland—the niece of Charles Callahan Perkins, one of the founders of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—to tell her about the Gardner commission.1 She revealed that Mr. Gardner paid more than she had asked, and she used the funds to help Italian friends who were in dire straits due to recent flooding.2 In January 1865 Lucia wrote to tell Catherine Gardner that Francesca was busy painting blooming laurustinus, apparently one of the patron’s favorite flowers, into the scene.3 A month later, Lucia wrote again to report that the painting was completed.4

It could take a month or more for letters to travel across land and sea between Florence and Boston. Around the time the Gardners received Lucia’s letter, they were mourning the death of their grandson, the only child of Jack and Isabella, who died in March 1865. Word of Jackie’s death reached Lucia quickly—an indication of the friendship between the families—and she sent her condolences less than five weeks later. Perhaps hoping to distract the grieving grandparents, she described Francesca’s painting in more detail, revealing that the background is “a literal copy of the view which you will remember, and there are flowers enough to suit you.”5

The view, extending across a valley to the Apennine range, would have been familiar to the Gardners from visits to the Alexanders’ home at Bellosguardo, the hilltop enclave popular with Anglo-Americans outside Florence’s walls. Francesca always captured the world around her with great fidelity, so we can assume the shrine, which no longer survives, would have been familiar, too. But she may have made up a detail to make the shrine even more interesting to her sophisticated patrons. The plaque below the holy figures is inscribed with Saint Bernard of Clairvaux’s prayer to the Virgin Mary, rather than a more traditional biblical verse. Although Bernard was not an especially well-known saint at this time, the prayer was familiar to nineteenth-century viewers due to its inclusion in Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (33:19–21), a fourteenth-century text that was exceptionally popular among Italophile Bostonians like the Gardners and Alexanders; Lucia described the 1865 celebrations in Florence marking the 600th anniversary of his birth in one of her letters to the couple.6 Francesca may have added the inscription, knowing it would be appealing to the Gardners.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

Francesca Alexander’s painting Decorating a Shrine, hanging above the textile case in the Short Gallery

Following the death of Jack’s parents in 1883 and 1884, he and Isabella must have inherited Francesca’s painting. It now hangs in the Museum’s Short Gallery, alongside prints and drawings as well as a number of paintings by nineteenth-century artists. Isabella too loved Florence and no doubt would have found the Dante reference appealing. She owned thirteen copies of the Divine Comedy and was one of the few female members of the Dante Society of America; in fact, she received a plaster cast of what was thought at the time to be the poet’s death mask as a gift from them in 1885.7

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (U27e60). See it in the Dante Case in the Long Gallery.

Unidentified maker, Copy after a cast of the "Death Mask" of Dante Alighieri, late 19th century. Plaster, height: 21.59 cm (8 1/2 in.)

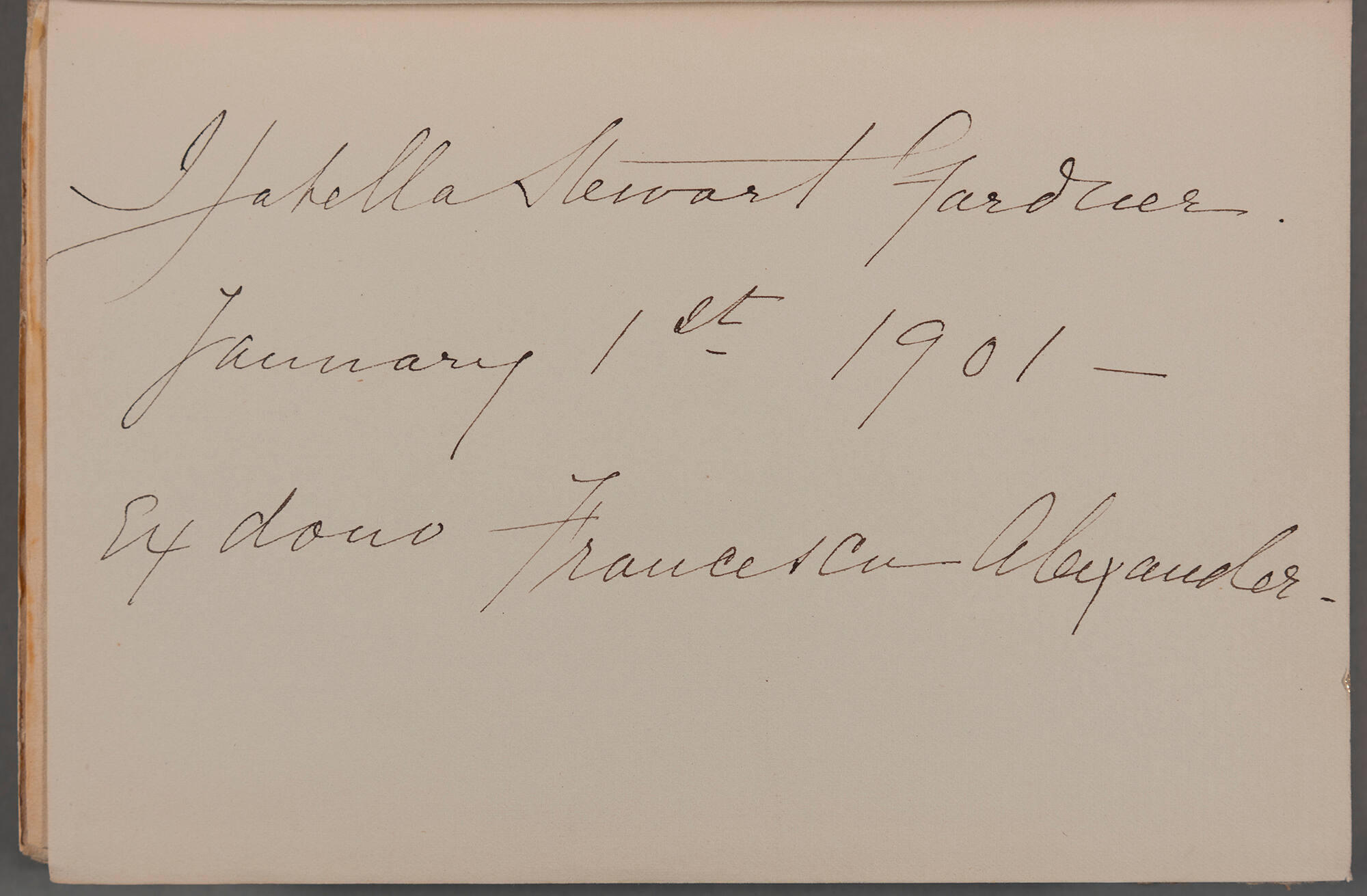

Jack and Isabella also acquired books by Francesca and Lucia. Francesca’s books described her Italian friends and translated the stories and songs she learned from them. John Ruskin met Francesca and her mother when he was in Florence in 1882; he was captivated by Francesca and her art. He purchased two of her manuscripts and shepherded them to publication, ensuring wide readership and acclaim. Isabella gave Jack a copy of Francesca’s Roadside Songs of Tuscany (1884) for Christmas 1884, and they also had copies of The Story of Ida (1883) and Christ’s Folk in the Apennine (1888). According to an inscription in Isabella’s hand, Francesca gave her a copy of Hidden Servants (1901) the year it was published. It isn’t signed—which was Francesca’s habit when she directly gifted copies to friends—so this copy may have been sent to Isabella by the Alexanders’ Boston-based financial managers, Charles and Alfred Bowditch, who helped facilitate these kinds of arrangements for the women. Bowditch probably also sent Isabella a copy of Lucia’s collection of translated saint stories entitled Libro d’Oro (1905); a printed card still in the volume states that it was from Mrs. Francis Alexander.

Each of these books is pristine; the bindings are solid and the pages seem virtually untouched, except for a tiny pressed flower in the pages of Christ’s Folk. But Isabella must have read them, as did so many in her social circle; Francesca’s stories about her Italian friends were well known. In a letter to Isabella in 1887, the Florence-based author Violet Paget, who wrote under the pseudonym Vernon Lee, described meeting a destitute Italian family and taking an interest in the two little girls. Violet helped put the girls in a convent school, a place “under the Invocation of Miss Alexander’s Santa Zita,” a reference to the Lucchese saint Francesca wrote about in Roadside Songs.8

**Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, Professor of Art, Wellesley College is the author of The Art and Life of Francesca Alexander 1837-1917 (2025)

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Isabella and the Dante Society

Read More on the Blog

Isabella’s Bookworm Friendship with Vernon Lee

Explore the Museum

The Short Gallery

Notes

1Letter from Francesca Alexander to Lilly Cleveland, 1 November 1864. John Ruskin Collection, New York Public Library.

2Letter from Francesca Alexander to Catherine Peabody Gardner, 10 November 1864. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.006384)

3Letter from Lucia Alexander to Catherine Peabody Gardner, 17 January 1865. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.001858)

4Letter from Lucia Alexander to Catherine Peabody Gardner, 17 February 1865. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.001859)

5Letter from Lucia Alexander to Catherine Peabody Gardner, 25 April 1865. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.001860)

6Letter from Lucia Alexander to Catherine Peabody Gardner, 25 April 1865. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.001860)

7Dakota Jackson, "Isabella and the Dante Society," Inside the Collection (blog), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2 November 2021, https://www.gardnermuseum.org/blog/isabella-and-dante-society

8Letter from Violet Paget to Isabella Stewart Gardner, 21 February 1887. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.004335)