Many details of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum theft are well known. In the early hours of March 18, 1990, two men dressed as police officers pushed the Museum buzzer, and stated they were responding to a disturbance. The guard on duty broke protocol and allowed them through the employee entrance. The thieves handcuffed him and a second security guard and tied them up in the basement of the Museum. Eighty-one minutes after they entered, the thieves departed with 13 works of art. What we don’t hear much about is what they left behind. Of those 13 works, five were paintings that were either removed or cut from their frames. These frames have a story all their own.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Dutch Room the day after thieves stole 13 works of art from the Museum, 18 March 1990

For centuries, people commonly reframed paintings as ownership, aesthetic tastes, and decorative surroundings changed. Often art dealers or owners repurposed and altered historic frames to fit a particular painting. But this resulted in unusual or sometimes unintended juxtapositions of different cultures and time periods. These five frames provide a window into late-19th and early-20th century preferences for framing works of art.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

Dutch Room with the empty frames, 2016

The Vermeer Frame

In one of her first major acquisitions, Gardner purchased The Concert by Johannes Vermeer at a Paris auction in 1892. It likely arrived with two very different frames to fit the painting. One is an ornate French frame from the second half of the 17th century. Close examination shows that this gilt frame, with carved flowers adorning each corner and separated by delicately inscribed central panels, was modified to fit the Vermeer. The top and bottom rails are cut down the middle so sections could be removed to create a narrower frame.

The second is in a black ripple molded frame. Ripple molding is a technique that uses a special tool to mechanically carve the appearance of small waves or ripples in the wood. This type of Northern European frame was first produced in the 17th century, aligning it with the date of The Concert. A year after purchasing this rare painting, Gardner’s friend Ralph Curtis wrote to her, “I marvel that you can get on seeing your Vermeer without a proper frame.” However it is unclear which frame he meant. Photographs of the painting in her Beacon Hill apartment in 1900 and subsequent years in the Museum always show it in the gilt frame.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (Marr2040)

Thomas E. Marr (Canadian-American, 1849–1910), The Drawing Room in the Gardners’ Residence, 152 Beacon Street, 1900, showing Vermeer’s The Concert in its French frame

Luckily, Gardner didn’t dispose of the black ripple molding frame. She repurposed it several years later to hold a textile fragment from an armorial hanging in the Early Italian Room. A gold label plate for the Vermeer is still attached to the bottom edge of the frame.

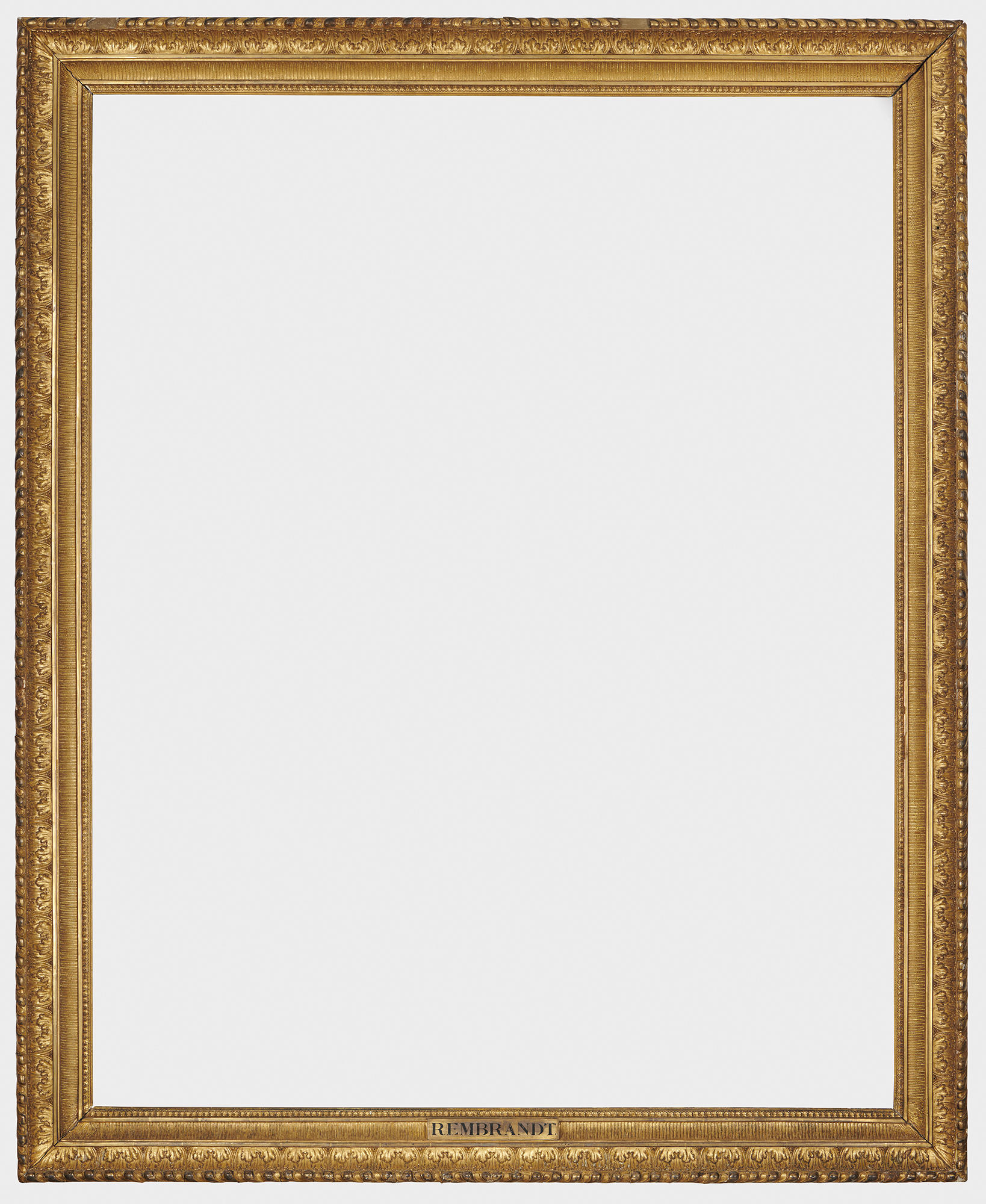

The Rembrandt Frames

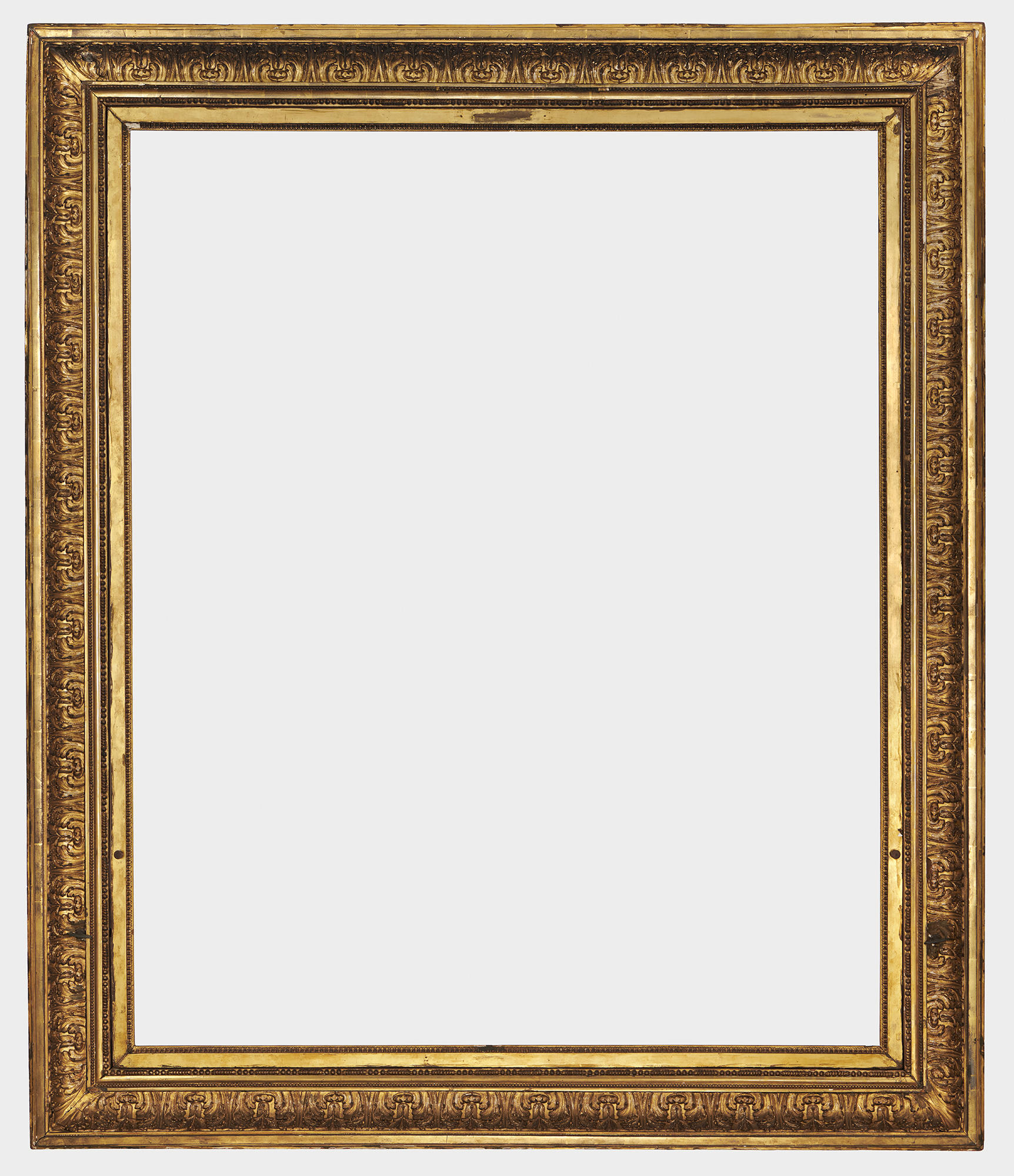

In 1898, Gardner purchased two large Rembrandt paintings through a London art dealer, who likely changed out the frames in advance of selling the 17th century works. While these large frames have several stylistic differences, both have characteristics common to the early-19th century. Each of the frames have multiple bands of ornament over classically inspired molding. The frame for Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee offers a small clue about its history with a label on the back that identifies a frame workshop in London. Like the Vermeer frame, examination of this one also reveals a previous history of alteration and some later modifications. Here it appears someone removed material along the inside edge to accommodate the larger size of this painting.

The frame for Lady and Gentleman in Black, French or English in origin, has distinct holes on the back in the upper and lower corners along the right side. These holes suggest a different orientation and probably secured hardware used to hang a horizontal shaped painting. However, the Rembrandt is vertical. Gardner Museum staff changed this frame once again at a much later date for an entirely different reason. It is one of many frames altered during World War II to allow for quick deinstallation of paintings in case of enemy invasion. Read more about frames during World War II in the blog post, Forever is a Long Time.

The same London dealer sold another Rembrandt painting (later reattributed to Rembrandt’s student, Govaert Flinck) to Gardner in 1900. Like the others, Landscape with an Obelisk probably arrived with a frame Isabella liked. The frame appears to be French and, while it likely dates to the late 19th century, it copies a 17th century style, aligning more appropriately with the time period of the painting. These reproduction style frames were popular with dealers and collectors around the turn of the 20th century.

Lingering Mysteries

The night of the theft, these four frames sustained minor damage when cast aside. Presumably the thieves were trying to make the Dutch paintings easier to transport. In another gallery one floor down, the thieves found Chez Tortoni in the Blue Room. The small 19th century Manet painting had a French 17th century gilt frame. Unlike the frames from the Dutch Room left on the floor of the gallery, the thieves left this frame on the opposite side of the Museum in a Security office. No one knows why they discarded this frame in that location—or removed it from the painting at all given its small size. It is one of the many lingering mysteries about the night of the theft.

The Museum repaired all five frames and returned them to the gallery walls as place holders in the hope that the stolen paintings will, one day, return to them.

The author would like to thank frame conservator Andrew Haines for his help with this post.

You May Also Like

Learn More

The Theft

Explore the Museum

The Dutch Room

Learn More

George Stout and Protecting the collection during WWII