For thousands of years, people have had a taste for nasturtiums. The value of this blooming vine as a food, medicine, and work of art has never escaped our appreciation. One of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s favorite flowers, the nasturtium has long symbolized freedom, strength, and independence. Such was her admiration for this colorful blossom, Isabella—a gifted gardener—began growing the vines in her greenhouses at Green Hill, her home in Brookline, Massachusetts. What came next was the creation of a spectacle out of a fairytale that only a true visionary could have imagined.

Hanging Nasturtiums Courtyard Display, 2021

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny PoreThe Nasturtium Tradition at the Gardner

Inside the Courtyard of the Museum, the hanging of the famed cascading nasturtiums is a harbinger of spring. Isabella established this annual tradition in celebration of her birthday on April 14. The unique display of brilliant orange nasturtium vines spilling down from the Venetian balconies of the Courtyard has inspired artists and visitors to her museum for over a hundred years. After a spring visit to the museum in 1913, Frances Brinley Wharton wrote to Mrs. Gardner:

I had such a vivid delight and wonder—and through [sic] it was but the merest glimpses—I have carried away beautiful visions of remembrance— …the golden charm of the young Rembrandt and that sombre Zubaran [sic] with the scarlet nasturtiums at his feet—and best of all perhaps the magical courtyard—with its long walls—[dropping] waters & masses of gorgeous sweet scented bloom—The color, and splendor and magnificence of this whole place.

The History of Nasturtiums

The garden nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus) has traveled slowly across the world to reach these heights of reverence. At different times in history, the nasturtium has been considered a vegetable, an herb, a flower, and a fruit. Indigenous to South America, its natural habitat is the tropical or subtropical montane forests of the Andes mountains. Prized by the ancient Incas of Peru as both salad vegetable and medicinal herb, wildcrafted nasturtiums were used to make tea to treat respiratory infections and as a poultice for cuts and burns.

Hanging Nasturtiums Courtyard Display, 2021

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

Imported to Europe by Spanish conquistadors around 1500, the nasturtium was introduced as a vegetable, along with the potato and tomato. First documented by Spanish botanist Nicolás Monardes in 1565, the nasturtium was noted as reaching England by John Gerard in 1597. At that time, the nasturtium was known to British growers as “Indian Cress” due to its origins in the Americas, then known as the Indies. It received its common name “nasturtium”—which in Latin translates to “nose-twister”—from Renaissance botanists due to its peppery flavor and spicy fragrance similar to watercress (Nasturtium officinale).

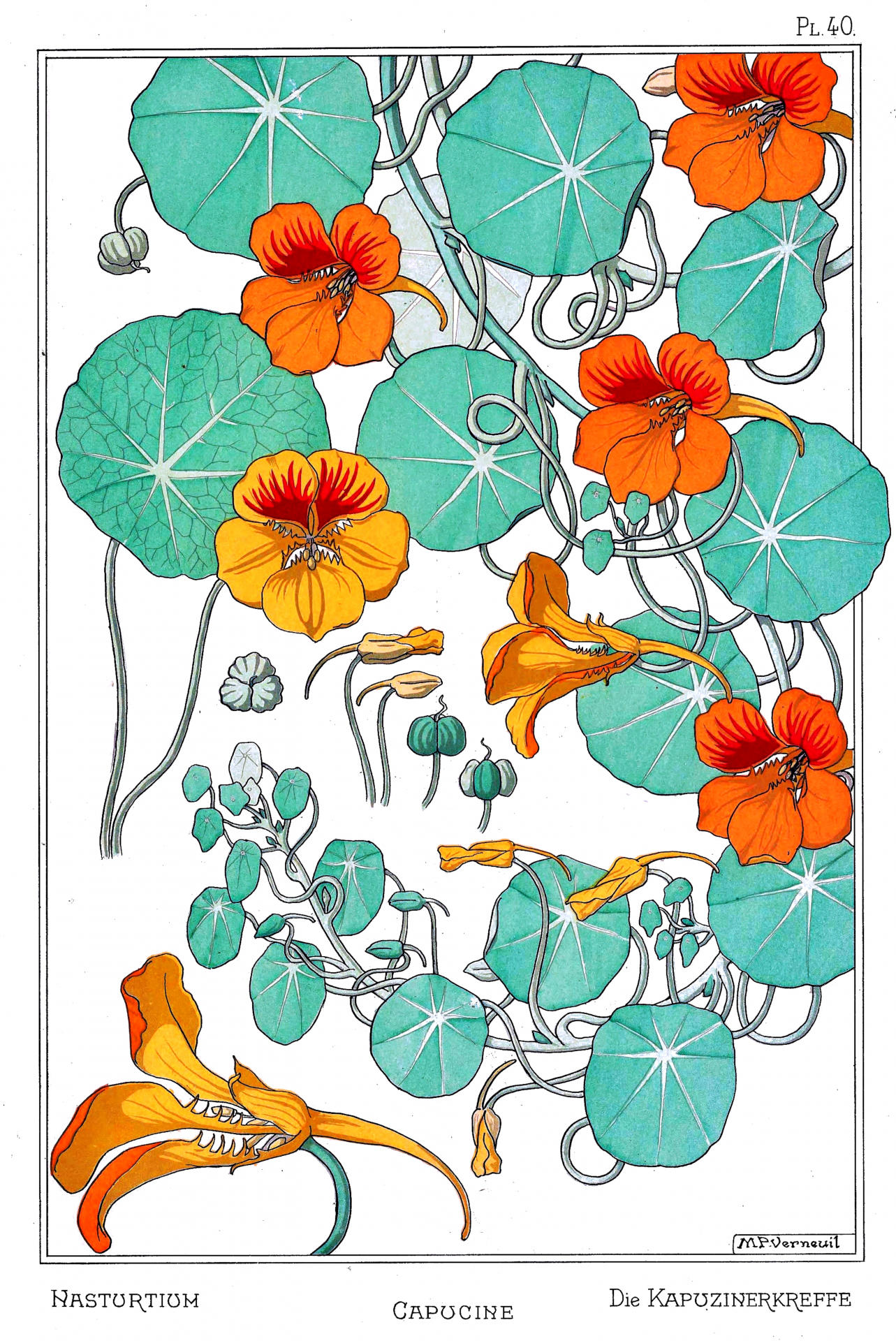

Maurice Pillard Verneuil (French, 1869 –1942, lithographer), Nasturtium from Eugene Grasset's Plants and their Application to Ornament, Paris, 1897. Lithograph with pochoir (stencil)

The nasturtium was one of the first New World plants to become popular in European flower gardens. The original nasturtium species to reach Europe (Tropaeolum minus)—a small yellow flower—is now rare. The more vigorous species, Tropaeolum majus, was introduced in the 1600s and gained adoration for its dark orange flowers, large rounded leaves, and climbing habit. It became especially popular as an ornamental after its display in the flower beds of King Louis XIV at the Palace of Versailles. This royal exhibition sparked the appreciation of the nasturtium as a work of living art.

Hanging Nasturtiums Courtyard Display, 2021

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

Nasturtiums came to North America with European immigrants as early as 1759. Thomas Jefferson first recorded planting nasturtiums in 1774, along with watercress, celery, and radicchio. He used the young, peppery leaves and flowers in salads and pickled the seeds and buds like capers. By 1782, Jefferson included nasturtiums in his lists of ornamentals. His gardening mentor, Bernard McMahon, first sold nasturtium seeds in the United States as an edible plant in 1803.

During the Victorian era, nasturtiums were just as popular for use in bouquets and table arrangements as for preventing scurvy. High in vitamin C, iron, and manganese, all parts of the plant above ground are edible and beneficial. With antiseptic, antifungal, and antibiotic properties, nasturtiums have been used as a traditional medicine for a multitude of purposes. During World War II, the pungent seeds were ground up and used as a substitute for black pepper which, at the time, was much more expensive and in short supply.

Jan Voerman (Dutch, 1857-1941), Nasturtiums, About 1894. Opaque watercolor on canvas

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See it in the Blue Room.

While traditional, single nasturtium flowers have five petals, there are also doubles and semi-doubles. The first semi-double was identified outside a Mexican convent in the 1920s. Seed distributor John Bodger cultivated and sold this variety named ‘Golden Gleam’ to the American public, and it became one of the most popular nasturtiums ever developed. All the rage during the Great Depression, the seeds cost five cents a piece. Nasturtiums from the ‘Gleam’ family are grown at the Museum to this day.

Artistic Inspiration

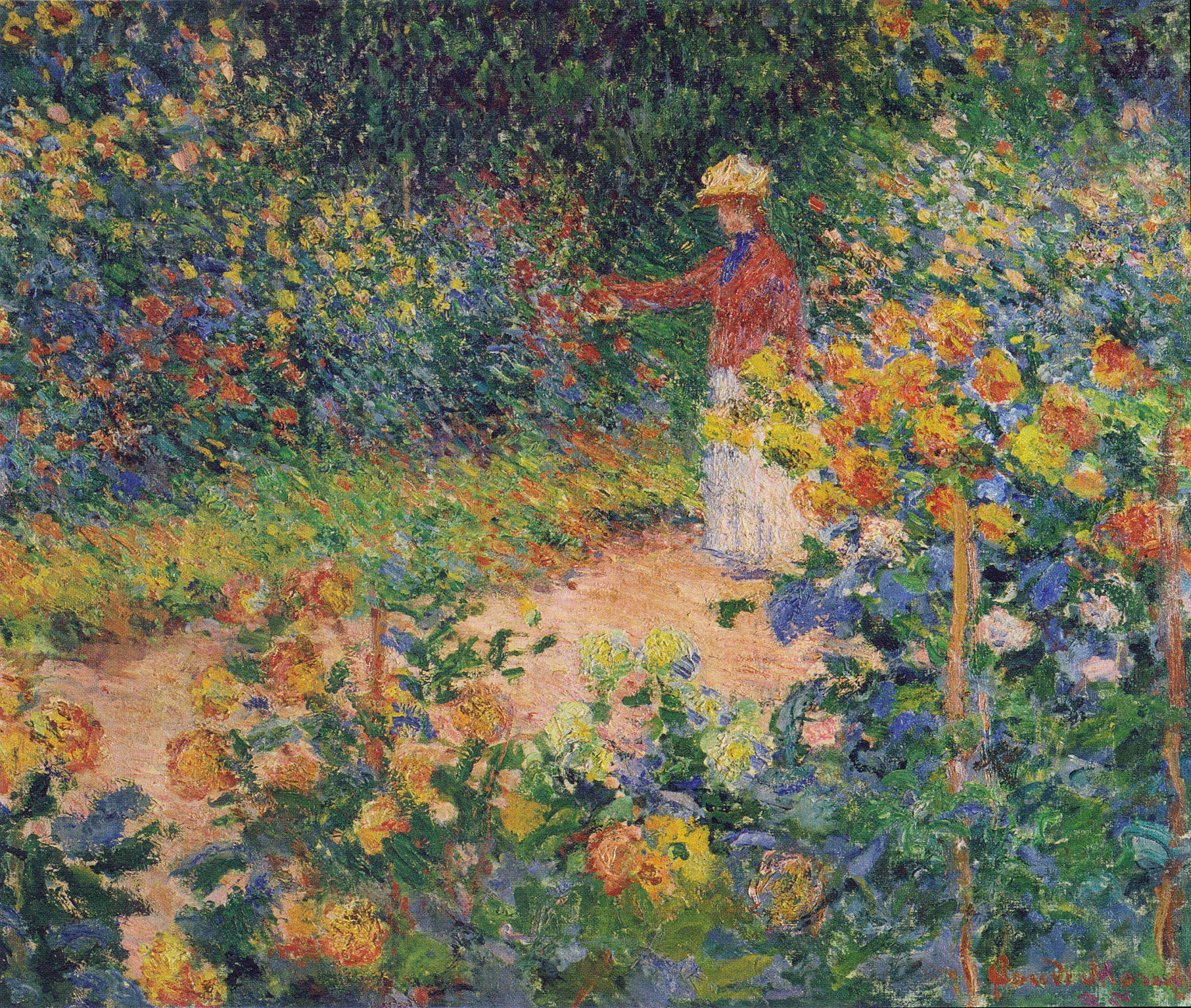

Both delicate and bold, the nasturtium has been a beloved subject of artists since the Victorian era. The nasturtium’s shape, color, and habit have inspired artists of all mediums –notably Tiffany glass, Moorcroft pottery, William Morris’ textiles, and Claude Monet, who grew nasturtiums annually along the walk of his gardens at Giverny.

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926), In the Garden, 1895. Oil on canvas

Bührle Foundation, Zurich, Switzerland

In the spring of 1919, Isabella Stewart Gardner’s grand nasturtium display was captured by artist Arthur Pope during one of his visits to the museum. His painting Nasturtiums at Fenway Court can be admired in the Museum’s Macknight Room. [Read more more about it in the blog post “One Hundred Years of Nasturtiums.”]

Arthur Pope’s Nasturtiums at Fenway Court, 1919, in the Macknight Room

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The nasturtiums make their divine—yet fleeting—appearance in the Courtyard for about three weeks each April. It takes nine months to grow nasturtium vines to lengths that would rival the locks of Rapunzel. Our team of horticulturists at the Gardner Museum is honored to carry on this tradition "for the education and enjoyment of the public forever."

You May Also Like

Nasturtiums: A Gardner Tradition

Learn More

Gift at the Gardner

Shop Nasturtiums

Installing the Nasturtiums

Watch a short video