In 1915, Isabella Stewart Gardner opened the only gallery in her Museum dedicated to a contemporary artist—the Macknight Room. Named after watercolor painter Dodge Macknight, the first-floor gallery is one of the only lasting public memories of the painter once known as Boston’s “king of Impressionists.”1 Not well known today, Macknight’s work fell out of favor as tastes changed— some critics referred to his vivid watercolors as “Macknightmares.”2 Isabella, however, respected and admired his work and the Macknight Room preserves a moment when he was on top of the Boston art world.

Photo: Sean Dungan

The Macknight Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Dodge Macknight’s Early Life and Training in Europe

Before Dodge Macknight became part of Gardner’s circle, he braved the path of other aspiring American artists at the end of the nineteenth century. Born in Providence, Rhode Island on October 1, 1860, William Dodge Macknight tried his hand at scenic painting, opera design, and teaching before traveling to Paris in search of artistic training.3 When Macknight crossed the Atlantic in the winter of 1884, he was ill-prepared with no French language skills and little professional experience. Near penniless (in true bohemian spirit) and without a portfolio, Macknight took a gamble and entered Fernand Cormon’s studio to learn academic painting.

Courtesy of Vose Galleries, Boston

Dodge Macknight, late 19th century

Although Macknight eventually found Cormon’s studio too conservative, his time in the studio introduced him to experimental painters, including Eugene Boch, John Russell, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Emile Bernard, and Vincent Van Gogh.4

Finding His Style and Return to the States

Amidst the increasing popularity of Impressionism, Macknight struggled to find his own artistic identity. However, by the beginning of the 1890s, Macknight found success rendering dazzling daylight and natural beauty in exuberant watercolor with paintings like The Bay, Belle-Île. Here, he dragged rich jewel-toned pigments over an over-wetted surface to capture depth and dimension on the water’s surface.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P11s33). See it in the Macknight Room.

Dodge MacKnight (American, 1860–1950), The Bay, Belle-Île, 1890. Watercolor on paper, 38 x 38 cm (14 15/16 x 14 15/16 in.)

Around this same time, Macknight met and married the governess of his friend John Russell. He and his new wife, Louise Queyrel, moved to Spain and had their first and only son, John Macknight. In 1897, facing tensions between the United States and Spain in the lead up to the Spanish-American War, the Macknight family found a home in East Sandwich, Massachusetts. Over the next few years, Macknight’s colorful views of New England and persistent self-promotion catapulted him into fame.

Were I Titian or Velazquez I would invite you to my studio and allow you to pick up a paint brush (the kings and queens used to amuse themselves then, did they not?)

Over the next few decades, Gardner and Macknight grew closer, and she became his most significant patron alongside collector Desmond Fitzgerald. Macknight and Gardner shared a love of travel, particularly to Mexico and Italy. Gardner visited Northern Mexico in the 1880s, and exchanged letters with Macknight during his journeys South in 1907, 1908, and 1909. The artist found the sun-drenched landscape both transformational and vexing, writing to Gardner in 1908, “What a fool a man is to try and paint la Nature! I believe I would laugh Ha! Ha! If the joke wasn’t on me. Curse the man who invented greens! How can you paint a green that is full of orange and red and violet and blue?”

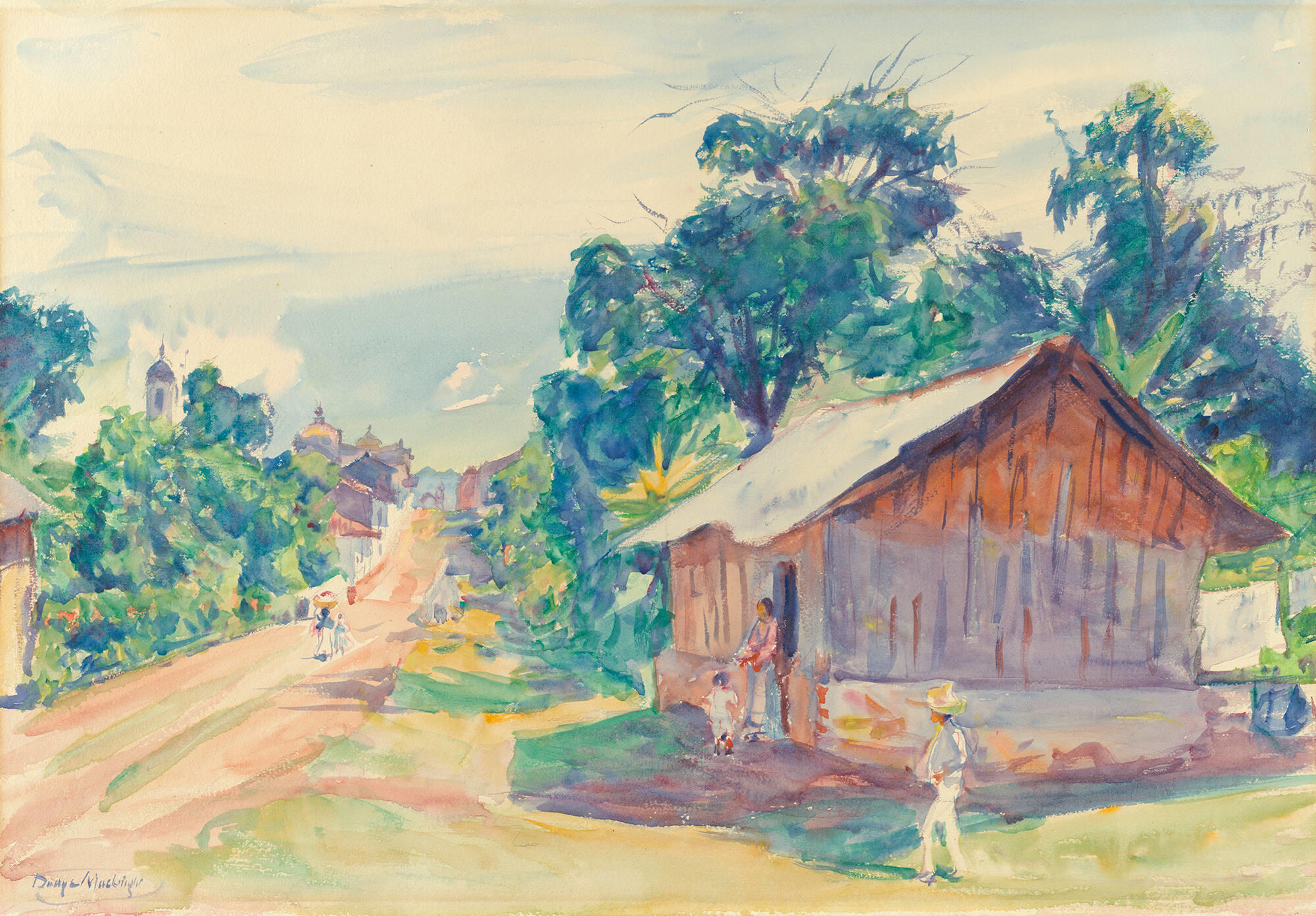

Gardner bought The Road to Córdoba, Mexico from his 1907 trip, hanging it on the south wall of the Macknight Room.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P11s30). See it in the Macknight Room.

Dodge MacKnight (American, 1860–1950), The Road to Córdoba, 1907. Watercolor on paper, 37 x 55 cm (14 9/16 x 21 5/8 in.)

Dodge Macknight’s Rise and Fall

Boston art critics praised Macknight’s paintings from Mexico, Jamaica, Newfoundland, Algeria, and beyond. The success of these pictures was two-fold: Macknight marketed himself as an avid, celebrity explorer, and he appealed to the armchair-explorer sentiment of Boston’s upper class. His paintings lent both the lively spirit and the cultured knowledge of worldly exploration to his patrons without the effort or discomfort of braving the landscape.

By the early 1920s, Macknight was at the height of his fame. In 1923, more than half the paintings exhibited at his longtime gallery Doll & Richards sold in less than twenty minutes, and the line down Park Street made headlines.5 But the death of Isabella Stewart Gardner, one of his major patrons and close friends, began an abrupt wind-down in Macknight’s production, and the death of his only son in 1928 ended the artist’s painting practice altogether.6 Macknight retreated to his garden in East Sandwich, and critical attention to his work dwindled shortly after.

Photo by Sean Dungan

The Macknight Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

His contributions to Boston’s history and American landscape painting, however, survive through the room his friend and patron Isabella Stewart Gardner dedicated to him. Today, the Museum embraces Isabella’s legacy of cultivating talent and supporting artists with an acclaimed Artist-in-Residence program, exhibitions, and programs.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Isabella Stewart Gardner and Mexico

Learn More

Contemporary Art

Read More on the Blog

American Impressionism and a Piano Trio

1"Mr. Macknight's Watercolors at Doll & Richards's," Boston Evening Transcript, 22 March 1902.

2A. E. Gallatin, American Water-Colourists, (New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, 1922). Gallatin also names Whistler, Homer, Sargent, Cassatt, Hassam, Marin, Demuth, Burchfield, and Walter Gay in his pantheon of American watercolor painters.

3Desmond Fitzgerald, Dodge Macknight: Water Color Painter, 6-7. Martin Bailey, “A Friend of van Gogh: Dodge Macknight and the Post-Impressionists: Despite Being Widely Admired in His Lifetime, the American Artist Dodge Macknight Is Now Largely Forgotten.

4Martin Bailey Reconstructs Macknight’s Life in Europe in the 1880s and 1890s, Revealing New Information about His Famous Friends, Including Van Gogh and Sisley,” Apollo (London, 1925) 165, no. 545 (2007), 28.

5“Half Of Exhibit Sold in 20 Minutes,” The Sandwich Independent, March 28, 1923.

6Notes on Dodge Macknight by Marise Fawsett, Box 2, The Archives and Letters of Marise Fawsett (1911-2006), Cape Cod historian, Sandwich Historical Commission Archives, Sandwich Public Library, Sandwich, MA.