A medieval doorway frames the passageway between the Spanish and East Cloisters of the Gardner Museum. This magnificent portal once graced the front steps of the Maison Seguin, a 12th-century house in La Réole France, located approximately 50 miles south of Bordeaux. Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased the carved sandstone assemblage in July 1916—shortly after the Maison was destroyed—sent it back to Boston, and installed it in her museum. In early 2020, the Gardner’s conservation department repaired the stone and took measures to improve its stability.

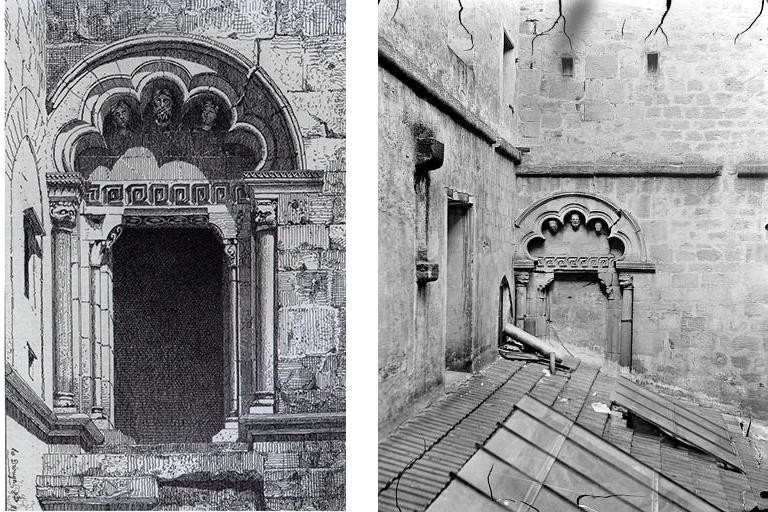

Left: Leo Drouyn (French, 1816-1896), La Réole, 1865; Right: Edgar Mareuse (French 1848-1926), Photograph of Maison Seguin, about 1900

An 1865 engraving and a photograph dating to about 1900 depict the portal in situ at the Maison Seguin. In these early images, you can already see some vertical cracking of the stone segments. In 1989, using the imaging technology gamma radiography, Gardner Museum conservators discovered steel dowels throughout the portal, including two that bridge a vertical crack in the right capital, atop the right column that supports the portal arch. In the 1980s and 1990s, conservators also documented new damage to the portal in the form of horizontal cracks radiating from the location of one of the dowels. Steel pins can corrode, as was likely the case here following exposure to high humidity that the portal endured before climate control was installed. Since corroded metal expands, this could have catalyzed the new cracks in the stone. At the time, conservators chose to focus on consolidating the stone surface of the portal, as they had not yet found a viable strategy to remove or stabilize the steel pins.

French, La Réole, Portal (detail), late 12th century, before treatment

In January 2020, monumental stone conservator Ivan Myjer and I began to examine the portal and create a plan to access the pins. Finding that portions of the stone were loose, we carefully removed the cracked fragments one-by-one, eventually exposing a hefty, six-inch-long dowel. As we had suspected, the dowel had started to corrode and expand, placing increased pressure on the adjacent stone.

French, La Réole, Portal (detail), late 12th century, during treatment

With additional time and care, we drilled into the soft, white setting material surrounding the pin and pried the damaged metal out of the stone cavity. Now that the stone fragments are replaced and the crack lines filled, the capital is more stable, and it appears intact for perhaps the first time in over 150 years.

French, La Réole, Portal (detail), late 12th century, after treatment

You Might Also Like

Building Isabella's Museum

How Isabella Stewart Gardner turned a stretch of marsh into a world-class museum

The Spanish Cloister

The Spanish Cloister reaches its crescendo in one of the Gardner Museum’s most iconic paintings

East, North, and West Cloisters

The red brick Romanesque-style Cloisters that surround the courtyard on the Museum’s ground floor provide a quiet frame around the dramatic four-story courtyard