Sitting proudly on a small table in the Spanish Chapel, over green damask fabric, is a beautiful 17th-century cross inlaid with mother-of-pearl and bone.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S6w1)

Palestinian, Cross, 17th century–18th century in the Spanish Chapel

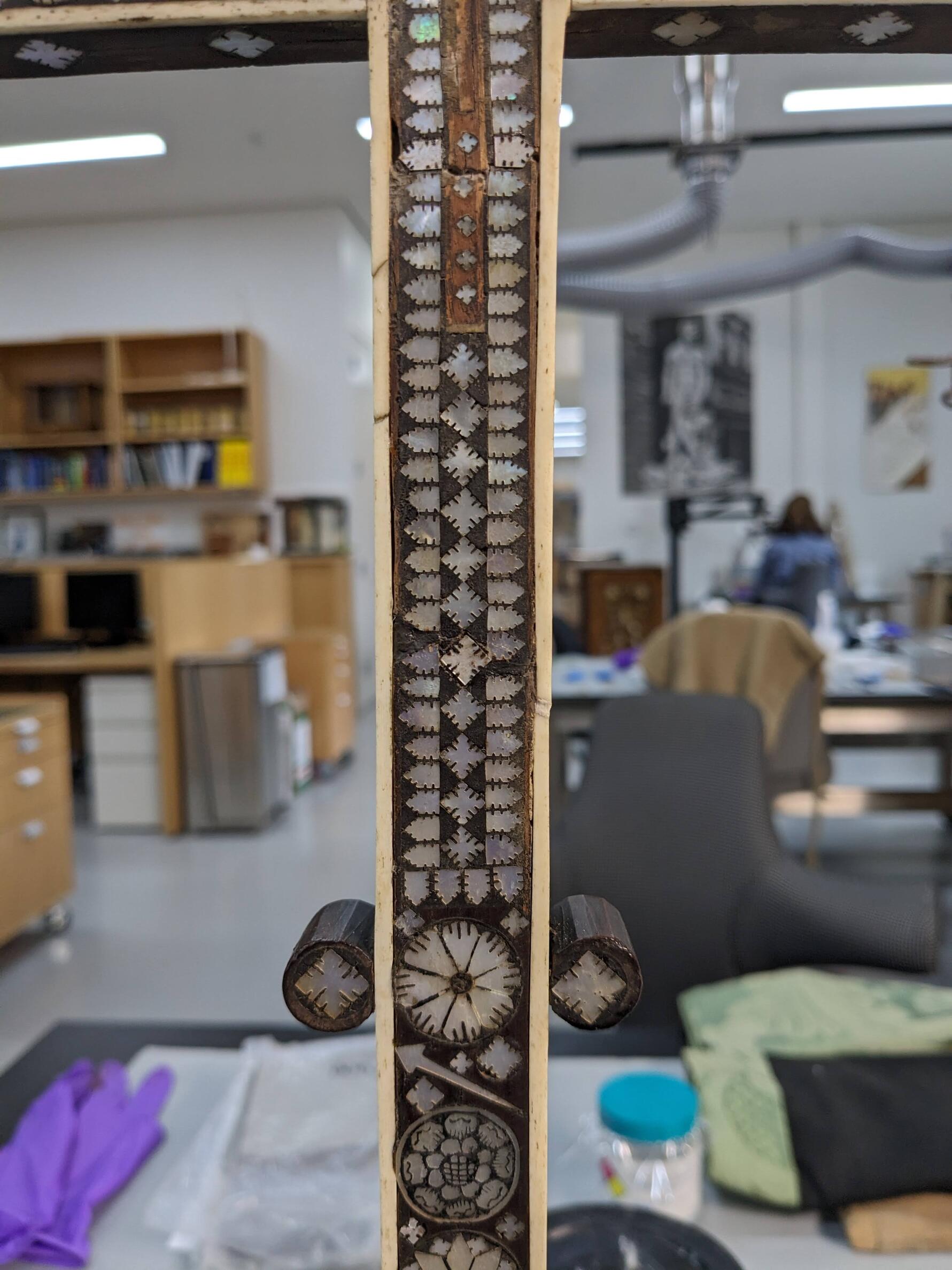

Mother-of-pearl inlay adorn the entire surfaces of this cross in various shapes and sizes creating a dazzling display laden with religious symbolism. For example, on the cross itself, three arrows represent the three nails used to crucify Jesus Christ. The mother-of-pearl tablet on the top of the cross is carved to look like a scroll and engraved with the initials "INRI" (“Lesus Nazarenus Rex Ludeorum'' or “Jesus Christ, King of the Jews”). On the base, a descending dove—the Christian symbol for the Holy Spirit—appears in a half circle surrounded by rays of light. Just below the dove are two crossed arms, one sleeved and one bare, with hands beneath a cross. This is the Franciscan Coat of Arms. The Franciscans are a religious order founded by Saint Francis of Assisi, who emphasized simplicity, humility and care for creation, in the 13th century. With all of this rich decorative detail, the front of the cross practically glows, reflecting shimmering light. Despite its luxurious detail, however, this cross was not in the best condition—its glow had been dimmed by dirt, wear, and older conservation treatments. This blog post highlights the cross’s treatment and—excitingly—describes how amid this treatment, museum staff were able to reattribute its origins, re-cataloguing it as Palestinian rather than Venetian.

Treatment

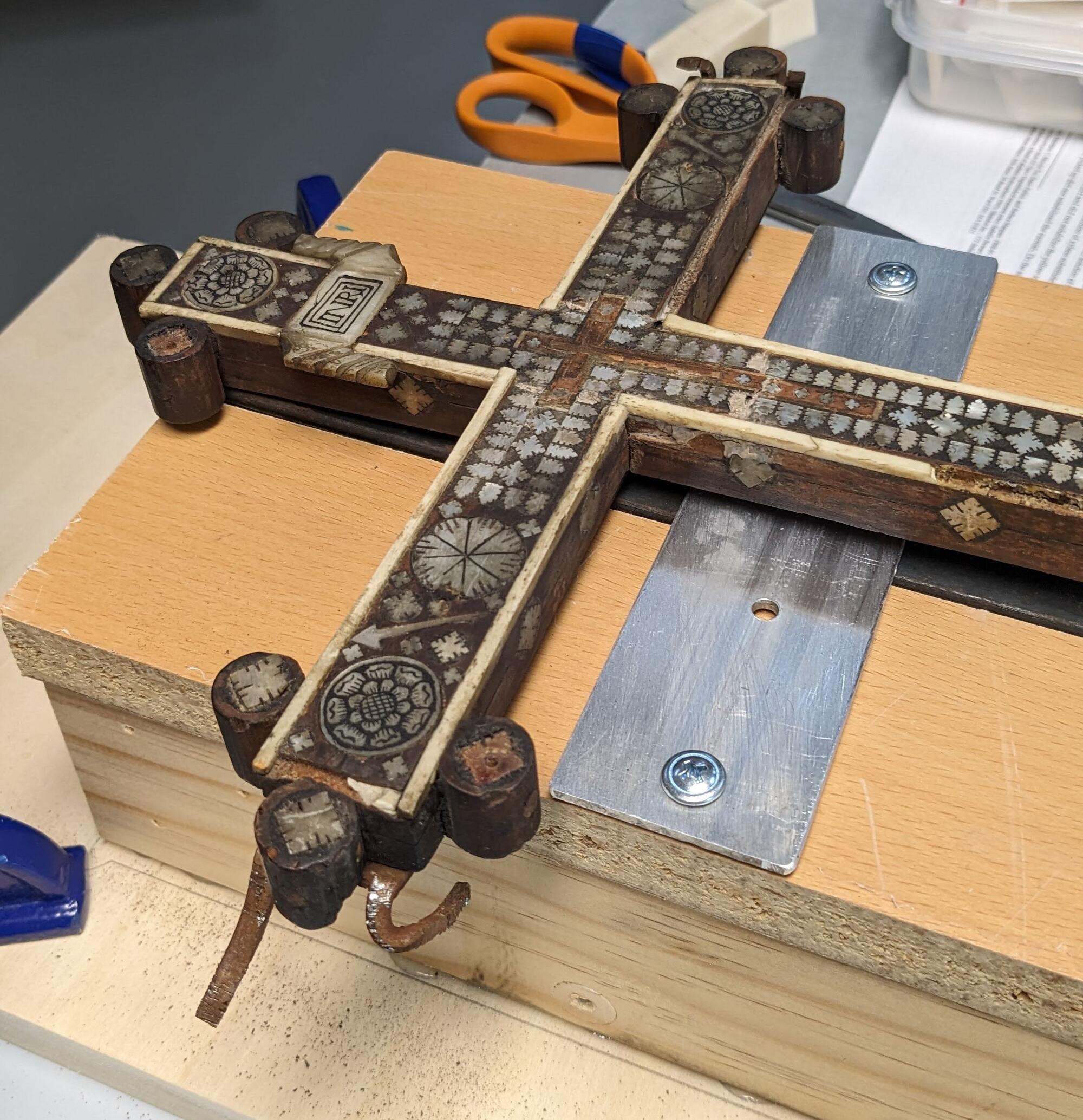

An initial assessment of the cross made several things very clear: it needed to be cleaned overall, there was a break in the middle that needed to be addressed and there were also many areas missing mother-of-pearl and bone inlays. First, it needed to be removed from an old, burdensome mount. Our preparator created a custom jig to secure the cross down while the metal mount was pried away from it. Once the cross was freed, the top half quickly separated from the bottom half—only the mount and old adhesive had been holding it together.

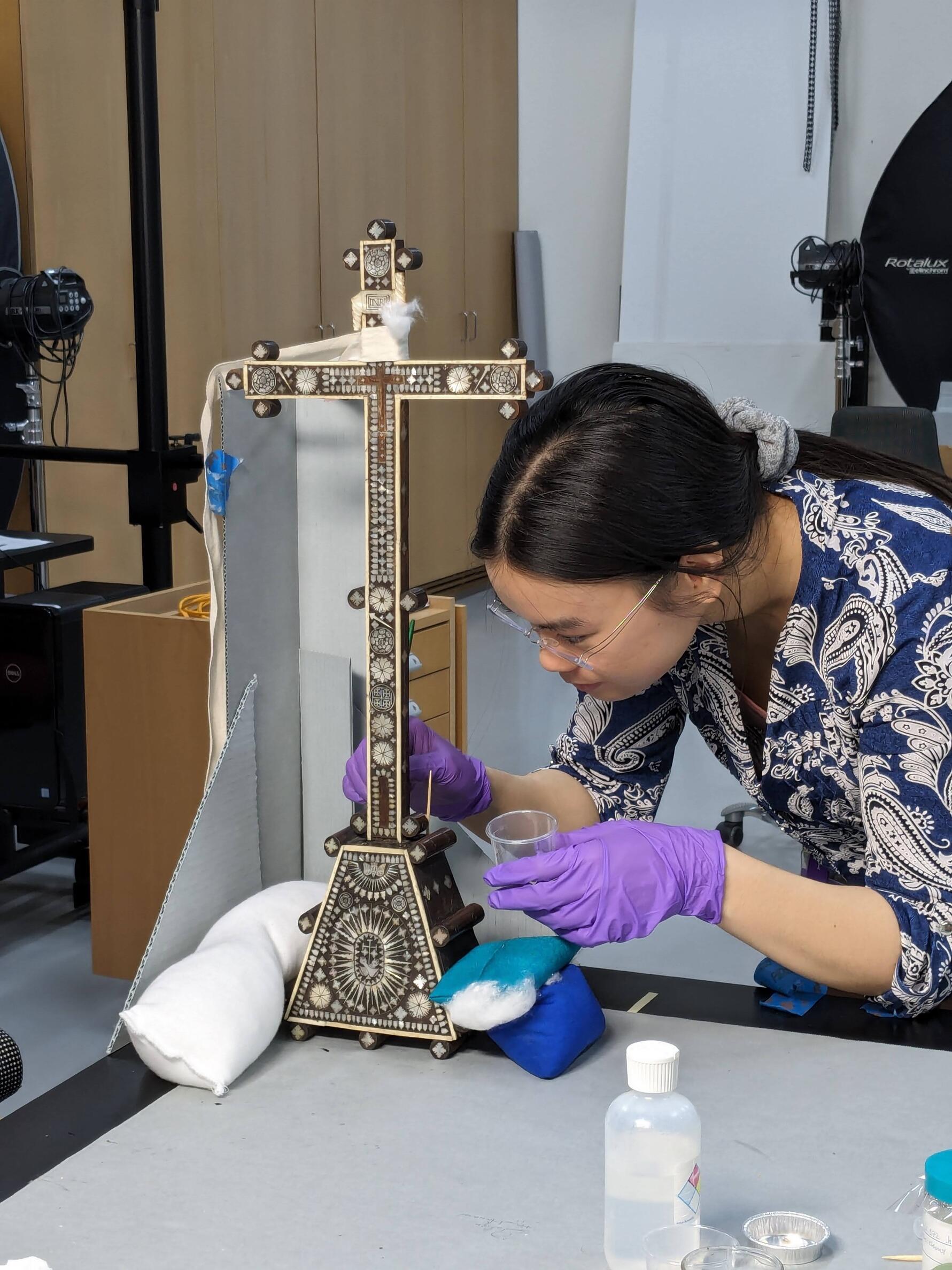

Now that the entire object could be accessed, it was dusted with the use of a soft brush and vacuum to remove surface dust and dirt. The mother-of-pearl inlays, bone edges and some areas of finished wood were cleaned with tiny cotton swabs dampened with saliva. As odd and antiquated as it may seem, saliva contains enzymes that break down organic compounds which makes it perfect for gently breaking down dust, dirt, and grime. Saliva cleaning is a proven conversation method!

Some of the larger decorative areas contain a thin metal border, and on the base of the cross, a section of the metal trim below the mother-of-pearl rays of light was straightened with a pair of tweezers wrapped in a thin film to avoid causing any damage to the metal. It was then reattached to the base with a conservation-grade acrylic resin.

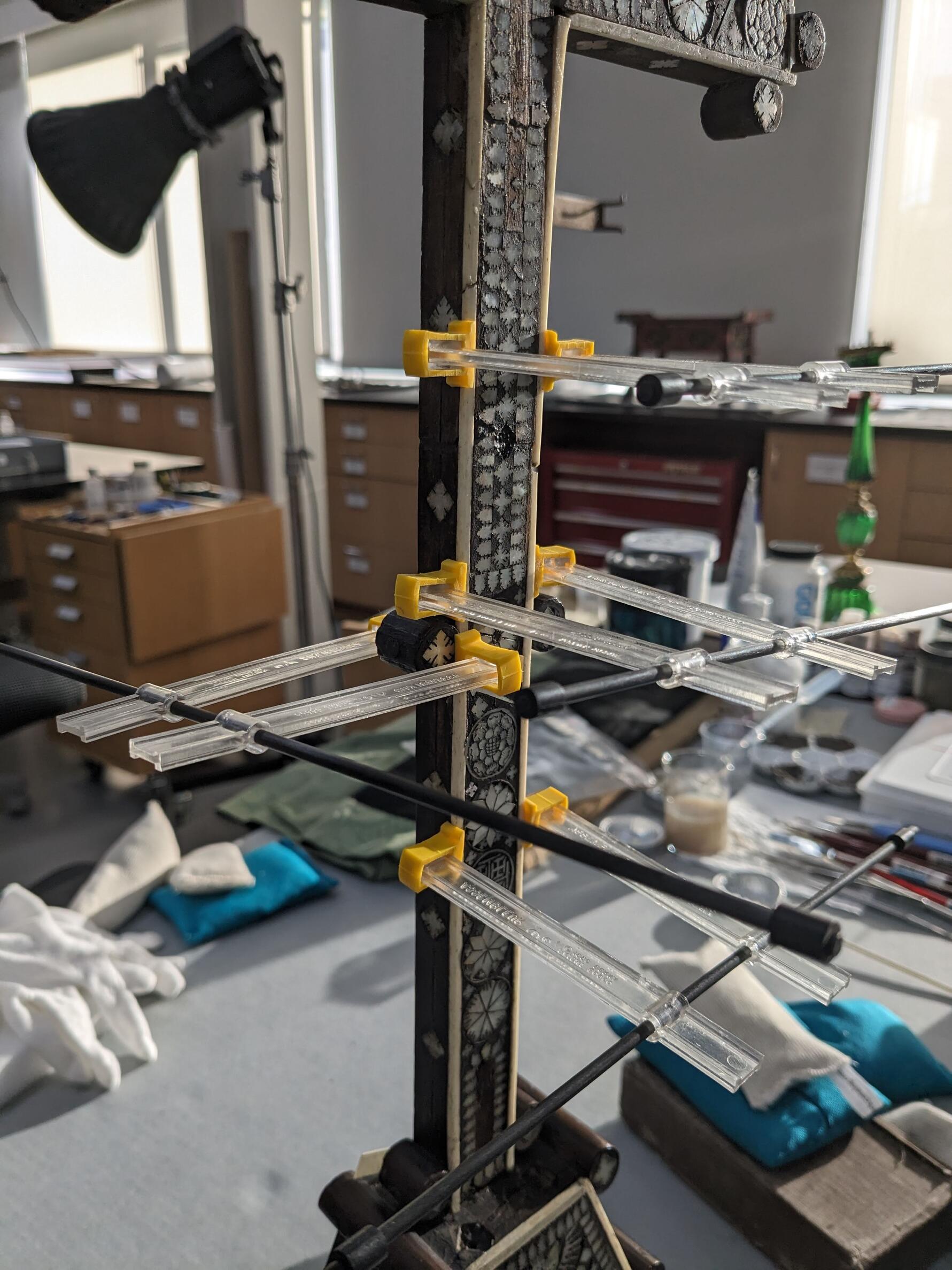

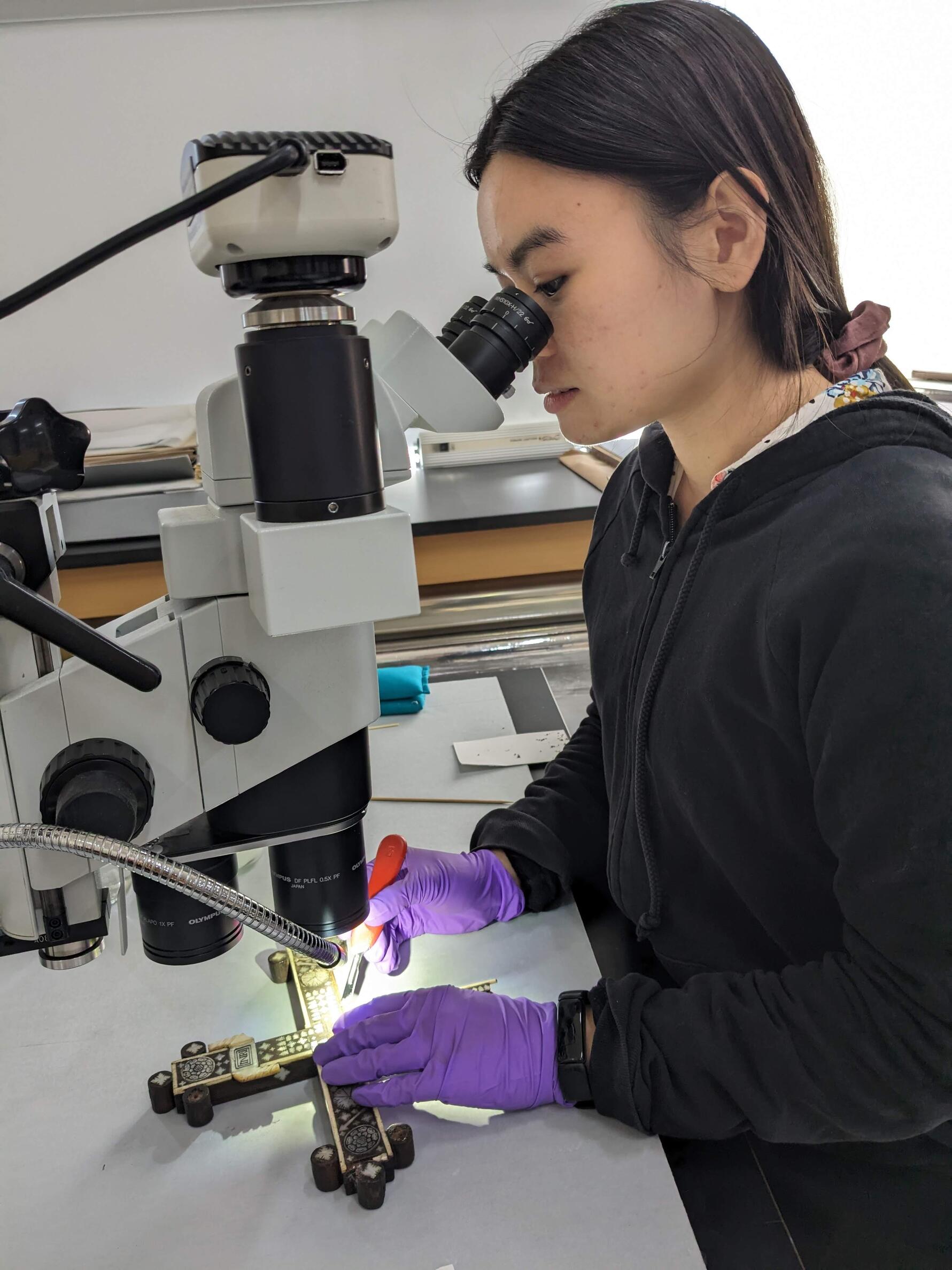

In areas of loss, leftover old, deteriorated adhesives needed to be removed before applying new adhesive for aesthetic and structural repairs. The old adhesive was softened with a water-based gel and then removed mechanically with saliva (very multi-purpose!) on dampened cotton swabs, a bamboo skewer, and a scalpel under a microscope.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S6w1)

Victoria Kitirattragarn, Conservation Technician, removing the old adhesive on the cross with a scalpel underneath magnification of a stereo microscope

Oh Mother of Pearl!

There were large and small areas where pieces of mother-of-pearl were missing entirely. To fill in these areas of loss, I decided to use a material to imitate mother-of-pearl rather than using the material itself. First, real mother-of-pearl is very difficult to shape and cut and, second, the imitation pieces will be easily identifiable by future conservators, even if virtually undetectable to viewers, in case the object needs to be treated again.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S6w1)

The Palestinian cross during conservation treatment with arrows indicating where there is mother-of-pearl loss

The replacement mother-of-pearl pieces are made of layers of handmade Japanese paper that was painted with acrylic paint and mica pigment powder. The painted paper was then covered with various films to adhere and imitate the signature shifting optical properties of real mother-of-pearl. The replacement inlay pieces were cut out from this painted Japanese paper/film sandwich into the proper shapes and attached to the object with a conservation-grade acrylic resin. The areas in-between the mother-of-pearl pieces were filled with a toned synthetic filler.

Bone fragments, saved in storage, were reattached with conservation-grade acrylic resin and missing bone edges were filled with strips of toned holly wood.

The Big Break

It was time to address the elephant in the room—this cross was still in two pieces! A decision had to be made about how to reattach the pieces. After consulting colleagues, it was clear drilling in shallow holes and inserting pegs to connect the two halves together would provide the best long-term stability.

Both cross pieces were laid horizontally with support, and a wooden sleeve was inserted over the break edge. The sleeve guided the drill bit to create three precise shallow holes in the broken parts of each half. Then using a combination of bamboo pegs and adhesive, the pieces were reattached together. It’s like the break was never there! Lastly, the cross was straightened by adding adhesive to its join on the pyramidal base.

Once the adhesive set, the cross was ready to go back to its original location in the Spanish Chapel—radiant as ever.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S6w1). See it in the Spanish Chapel

Palestinian, Cross, 17th century–18th century, before and after the 2023–2024 treatment

Location, Location, Location: Research and Reattribution

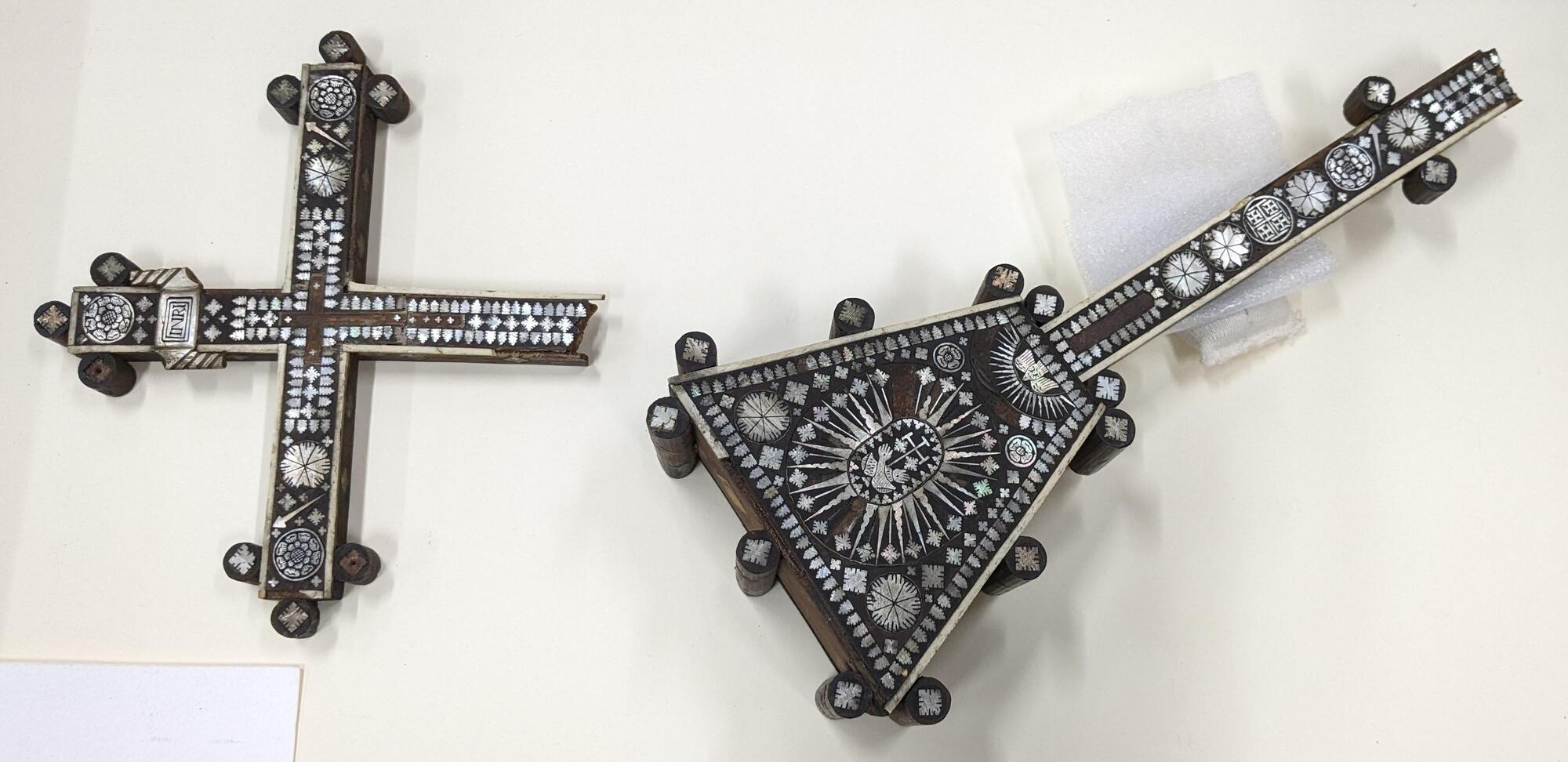

While the treatment was steadily progressing, so was some very interesting research! This object, and a similar, smaller cross in our collection, were originally cataloged as being Venetian because Isabella purchased them in Venice in the late 1800s.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S6w1) and (S33s73). See them in the Spanish Chapel and the Vatichino.

Two Palestinian, Crosses, 17th century–18th century. Carved wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl and bone, left: 59.7 x 25.1 x 8.9 cm (23 1/2 x 9 7/8 x 3 1/2 in.) and right: 40.2 x 15.9 cm (15 13/16 x 6 1/4 in.)

However, we were contacted by colleagues—both a curator and a conservator—from the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) who had been in Boston to visit the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) to conduct research and close examination on an exceptional model of the Holy Sepulchre, which was made in a Franciscan workshop in Bethlehem in Palestine. Looking at the materials and decoration of our crosses, they were convinced that they came from the same workshop that made the models. These objects are not, in fact, Italian, but rather Palestinian!

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (2016.91)

Probably Jerusalem, possibly Bethlehem, late 17th or early 18th century, 29.8 × 49.5 × 58.4 cm (11 3/4 × 19 1/2 × 23 in.)

While the stylistic and material similarities seemed clear, we wanted to gather more evidence to back up this attribution. First, we identified the bone used for the decoration as camel bone—a strong indication that these objects are from the Middle East. Furthermore, with the help of colleagues from the AGO, we contacted the Smithsonian to use a wood identification technique, Direct Analysis in Real-Time Mass Spectrometry (DART-MS). (Fun fact: this analysis technique is frequently used by the U.S Fish and Wildlife to identify illegal timber that is being transported into the U.S.) This allows us to identify the wood of the cross without taking large samples.

Using wood samples gathered while repairing the break in the cross, this technique identified all the wood samples as olive wood (Olea sp.). We know workshops in Bethlehem used mainly olive and some pistachio wood, so this is another strong piece of evidence that the cross is Palestinian. The chance to repair the cross and use conservation techniques to reattribute its origins is a wonderful example of how curatorial and conservation research can work together to uncover hidden stories about Isabella’s rich collection of objects.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Treatment of Mother-of-Pearl, Bone and Wooden Cross

Explore the Museum

Spanish Chapel

Read More on the Blog

Beger Sølv- The Gardner’s Hanseatic Beaker