Under the shelter of the atrium, a quartet of Australian tree ferns anchors the corners of the Gardner Museum’s Courtyard mosaic. Absent the winds and storms of their native habitat, they thrive, though pot-bound and still. Deprived of the humidity they crave—as the environmental needs of the art collection are paramount—horticulturists must tend to their thirst. The tree fern’s capacity to thrive for decades under glass is evidence of its extraordinary resilience.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

Tree fern in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2024

Ferns have long captured our imagination, inspiring folklore of enchanted forests. The reason for this association with magic is quite innocent. Before understanding reproduction by spores in the 18th century, people assumed fern seeds must be invisible and, therefore, grant invisibility.

We have the receipt of fern-seed, we walk invisible.

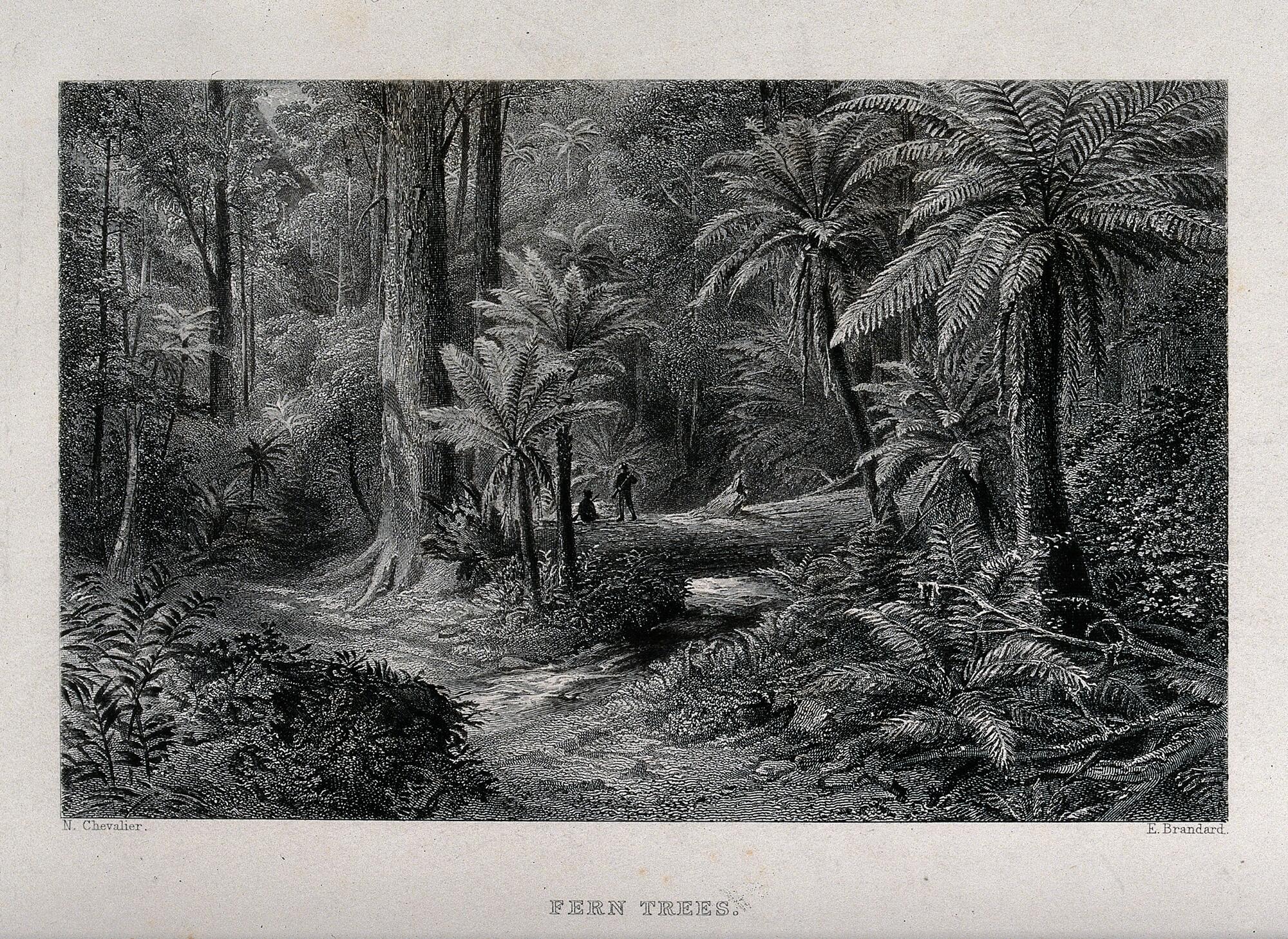

Wellcome Collection (20961i), https://wellcomecollection.org/works/aa6jssus

Edward Paxman Brandard (British, 1819–1898), after Nicolas Chevalier (1828–1892) Tree-Ferns in an Australian Forest with Two Hunters in the Distance, about 1873. Engraving

The Prehistory of Tree Ferns

Long before humans walked the Earth, ferns have graced the path. Indigenous to every continent but Antarctica, ferns have flourished since the continents were one and have evolved to survive the darkness of the forest understory. Tree ferns are true ferns, not trees. The trunk is not woody tissue but a solid accumulation of rhizomes. Species of tree ferns can grow 80 feet tall and live hundreds of years. The lacy tree fern—Sphaeropteris cooperi—is native to the humid rainforests of eastern Australia. Its fossil record stretches back to the Late Jurassic period, around 150 million years ago. The pulp of the trunk—a good source of starch—was food for dinosaurs and later, aboriginal peoples.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

Cross section of a tree fern trunk in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2024

Collecting Ferns

Tree ferns first reached the United Kingdom in the 19th century aboard ships returning from Australia. The trunks were used as weights to prevent the movement of more precious cargo in heavy seas. The dense hairs of the downy trunks were used to stuff pillows and mattresses. Once discarded on the damp British soil, some trunks began to grow new fronds, reaching for the sun. Because of its resilience, the tree fern found a place in lush captivity. Victorian heated conservatories—known as ferneries—were designed to embrace the tropical flora collected from distant lands.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Jenny Pore

A quartet of tree ferns in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2023

A stroll through the woods evokes an air of reverie that can be habit-forming. Ancient Egyptians first brought potted ferns and palms into their homes and tombs over 5,000 years ago. The desire to adopt a plant from the wild has only deepened with time.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.008377)

American, Brookline, Fern, late 19th century. Gelatin silver print

The Industrial Revolution fostered advances in glassmaking and indoor heating that enabled the cultivation of tropical houseplants in temperate climates. Yet the fumes from coal fires and gas lanterns were hard on delicate plants. In 1829, Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward used a glass container of damp soil to study the sphinx moth. Water vapor condensed on the glass, fell back on the soil, and created a constant humidity that allowed a fern spore to germinate. Ward had created the Wardian case—the blueprint of the terrarium. Fern collecting spread across the social spectrum during the Victorian fern craze—Pteridomania. Wealthy plant collectors like Isabella could afford heated shade house conservatories in order to grow large majestic trees. In the greenhouses of her estate at Green Hill, Isabella cultivated a variety of tree ferns.

Tree Ferns at the Gardner

Tree ferns are among the few plants resilient enough to withstand the filtered light of the atrium year round. The last quartet of tree ferns prospered in the space for over 30 years. When they were replaced by the next generation in early 2024, the tree ferns had stretched to reach the palace’s second story, towering over the ancient statues of the Courtyard. Cut from their pots, the trunks were laid out to freeze through the winter and were harvested as a growing medium for our orchid collection.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo; Jenny Pore

Towering tree ferns in the Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2021

Our current tree ferns had been waiting for their turn in the Courtyard for the last 10 years. The living collection is primarily cultivated in our Museum’s nursery, with 10,000 square feet of growing space under glass. This is where Gardner horticulturists nurture the permanent collection and propagate for the seasonal displays that keep the Courtyard garden in perpetual bloom.

Isabella Stewart Gardner traveled the world in search of treasures for her museum. She stipulated in her will that the installations she created would stay in place forever. Yet while the galleries are frozen, the flora of the Courtyard is always changing. The foliage plants that grow perennially among the marble sculptures are works of art themselves. A living fossil of the primeval forest, the tree fern is a tether through time. In a four-story terrarium in Boston, gossamer fronds unfurl in the still of the palace air.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

The Spirit of Violets

Explore the Museum

Seasonal Courtyard Displays

Read More on the Blog

The Auspicious Arrival of the Jade: Herald of Good Fortune