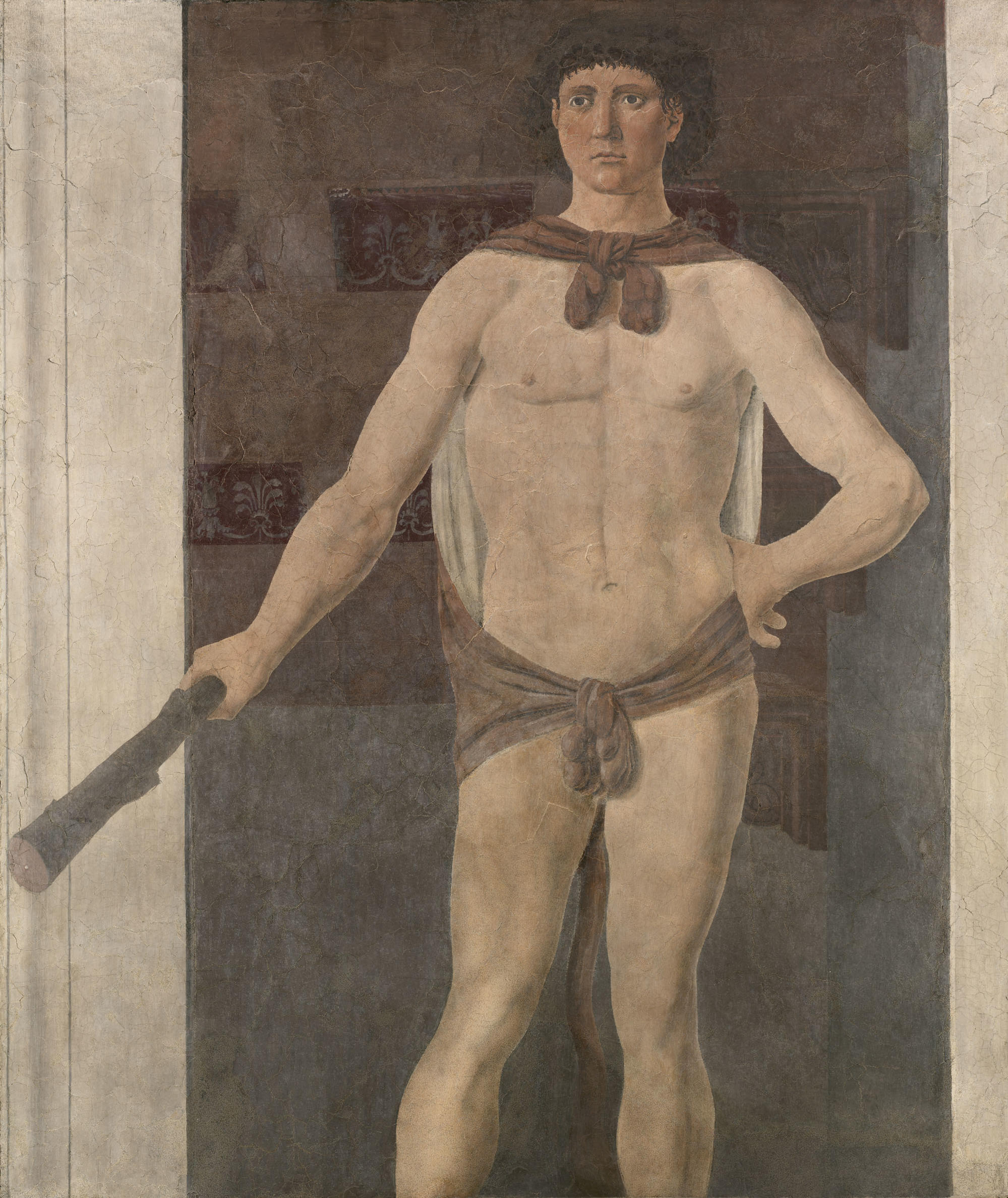

The Renaissance artist, Piero della Francesca, created this image of a youthful Hercules for a wall of his own private home.

Piero della Francesca (Italian, about 1415–1492), Hercules, about 1470. Purchased by Isabella Stewart Gardner from the dealer Elia Volpi, Florence, for 200,000 lire in 1906 (about $864,000 today) through the American artist Joseph Lindon Smith

For some reason, the lower portion of the fresco was missing. But an even greater intrigue eventually surrounded this piece, one that embroiled Isabella in a scandal.

After a decade of acquisitions, Isabella Stewart Gardner's collection was already impressive. But there was always room for more. In 1902, she received a letter from her friend and advisor, artist Joseph Lindon Smith. The Florentine art dealer Elia Volpi had shown him a photograph of Hercules by Piero della Francesca. The fresco—a wall painting on plaster—had been detached from the wall of the artist's house and was now for sale.

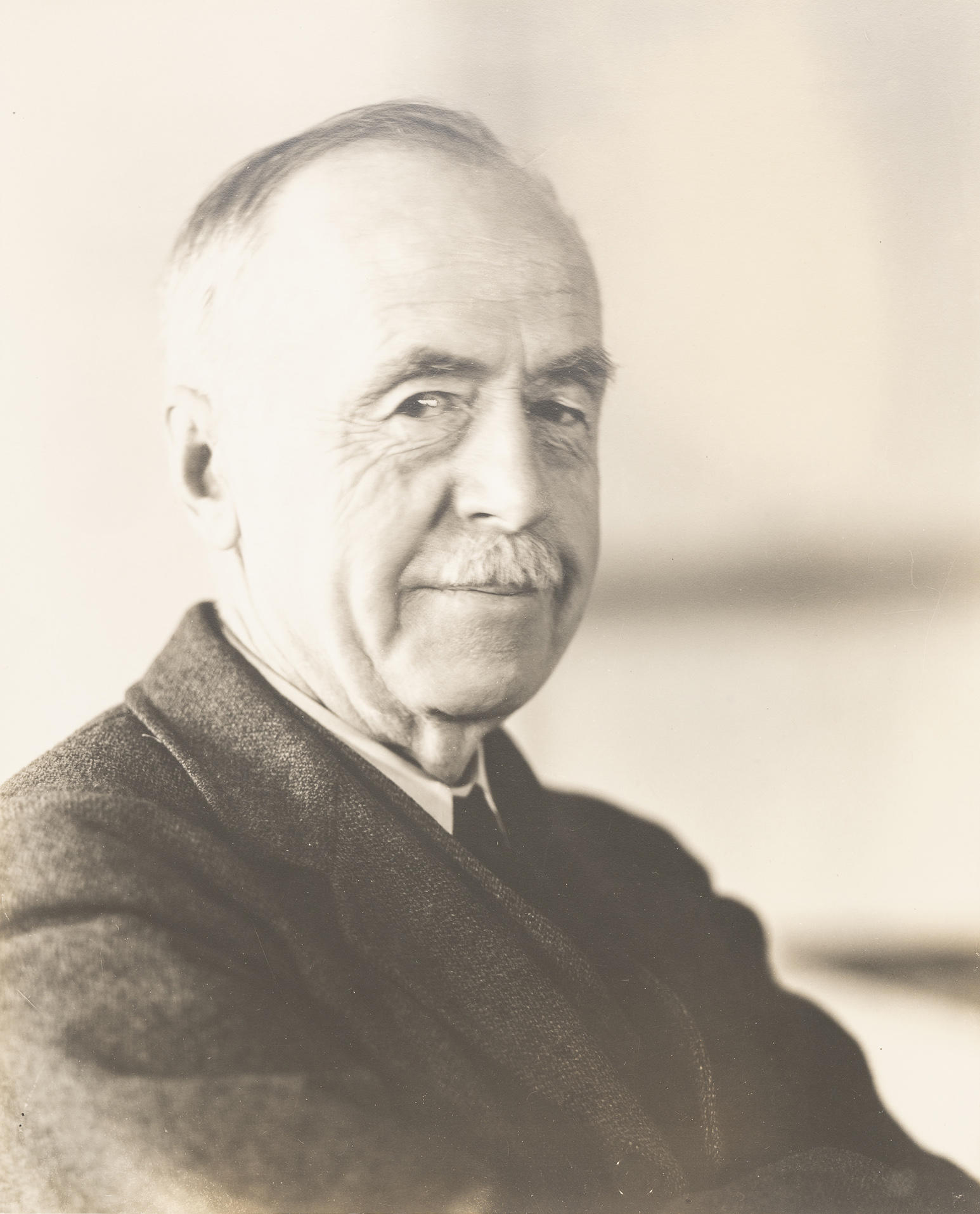

Gardner had a high opinion of Joseph Lindon Smith and his eye for art; Smith was a successful painter and shared Gardner's love of travel and discovery. Having spent time in Italy, he knew where to look and who to ask. Art dealers showed him works of art, knowing that he may be looking on behalf of Gardner and her growing collection in Boston.

The moment Gardner saw the black and white photo of Hercules, she knew she had to have it, writing to Smith, “buy instantly… and hurrah boys if I get it!” But matters of state halted the process: Italy changed its regulations on the sale and export of artworks. Along with many other works intended for Gilded Age collections in America and Europe, Hercules was stopped from leaving Europe.

For five years, the only image Gardner had of Hercules was a watercolor reproduction. The artist faithfully captured even the cracks in the four-hundred-year-old fresco. Elia Volpi had commissioned this watercolor and had it sent to Gardner to demonstrate—in the era of black and white photography—what the classical hero looked like in full color.

Watercolor of Piero della Francesca’s Hercules, about 1903

Joseph Lindon Smith wrote in a letter to Isabella’s regular agent in Paris, Fernand Robert, “Volpi has repeatedly written to and seen the various Ministers responsible for this law, and has done his best to have our picture taken off the list—giving as one excuse the fact that negotiations between him and me had already been begun…”

Gardner’s delay was one sign of the winds of change sweeping the art world. European citizens previously willing to profit from the sale of their artistic heritage suddenly embraced an emerging movement to “save” works of art for their countries. When Gardner’s American contemporary Henry Clay Frick bought a portrait of Queen Christina of Sweden by Hans Holbein in England, news of the sale provoked a public outcry, satirized in this Punch cartoon and dramatized in a short story by writer Henry James. Outraged English citizens donated money to a public fund to match Frick’s price, ultimately saving “their” painting for the nation.

A greedy Uncle Sam tries to abduct the painting of Queen Christina and bring her to America

The purchase of Gardner’s Hercules, by contrast, ultimately went through at the end of 1906. But due to costly US import taxes, it remained in Europe. Gardner’s friend Emily Chadbourne offered to store Hercules in her home in London, and Gardner agreed. When Chadbourne returned to the US in 1908, she illegally imported the painting by including it with her “household goods.” This was done without Gardner's knowledge, or so she claimed. Customs officials later discovered the undeclared artwork. The incident caused a scandal in the press, and Gardner paid a steep fine.

An article on the Chadbourne affair, “Government May Bring Civil Suit,” Boston Globe, 22 August 1908

Bringing the painting to Boston was a Herculean effort, and one that showcased the loyalty of Gardner's friends and supporters. In the end, her “indefatigable search for art treasures” made her the first collector who managed to bring a painting by Piero della Francesca to America.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Explore the Collection

Creating the Titian Room

Explore the Museum

Visit the Early Italian Room

Explore the Collection

Giorgio Vasari (Italian, 1511–1574), Musicians, about 1545