Cafe G is closed for repairs from January 29 through February 16, 2026.

We apologize for the inconvenience.

Gold: From Africa to Europe and Beyond

Gold shimmers from every corner of Simone Martini’s altarpiece. Prized by artists for its luster, malleability, and resistance to tarnish, and by patrons for its rarity and intrinsic value, gold honored the kingdom of Heaven and commanded the attention of congregations. As the matrix of Christian paintings, the use of gold surfaces pointed East, deriving authority from the icons of Byzantium, often understood as relics of early Christian antiquity and tangible connections to the Holy Land. But they also pointed south. Forged from the currency of international trade, Simone’s gold surfaces evoked the mines of Africa’s Sahel region, the trans-Saharan trade routes that brought this gold across the desert, and the Muslim empires of the continent’s Mediterranean coast whose ports sent it to Europe.

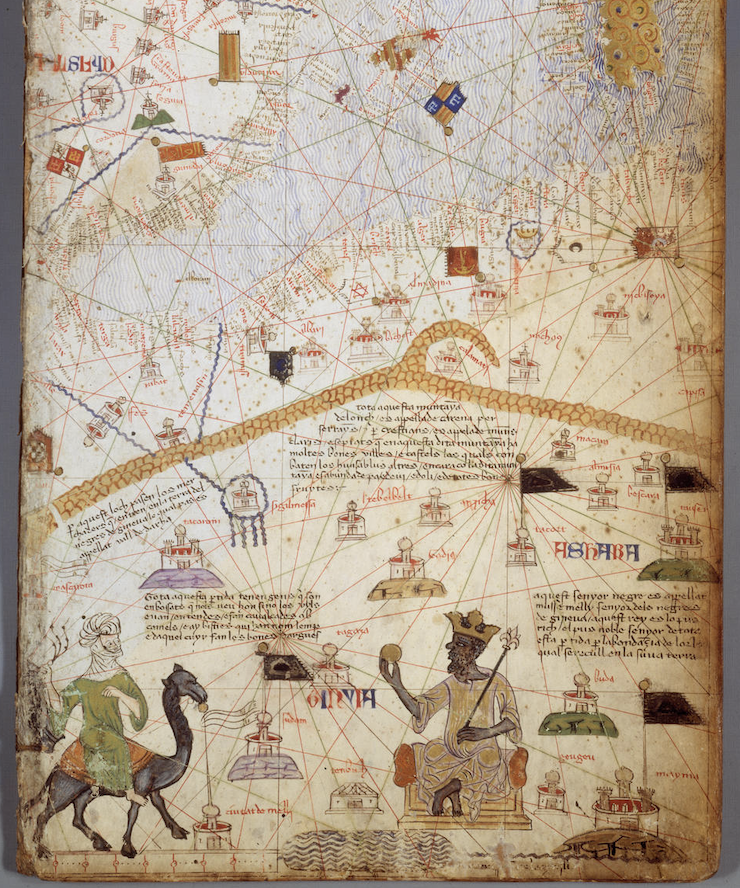

African gold transformed Europe. By the early 1300s, the Empire of Mali was the world’s leading supplier of gold. It exported gold powder and nuggets across the Sahara Desert, through cultural and trading hubs like Timbuktu, to the Muslim empires of North Africa that minted their own coins, or dinars, or sent the raw material onward across the Mediterranean. Malian gold exports revolutionized the economies of Florence and Venice, cities that had readopted a gold standard in 1252. Coins minted in both epicenters of global finance were transformed into gossamer-thin sheets, called gold leaf, which painters purchased for their workshops.

Africa as the land of gold captured the European imagination. In the 1320s, when Simone produced this altarpiece, Mansa Musa, the Muslim emperor of Mali, made his pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca. Observers singled out the epic journey for its magnificence, marveling at his retinue, the sheer number of enslaved people it included, and the vast tributes of gold distributed along the way (so much that it depressed market prices). For Europeans, including the royal owner of this map (at bottom right), Musa represented a new era of transcontinental trade as “the Black lord…the richest, and noblest, lord in the whole region, because of the abundance of gold obtained in his land.” He holds a gold nugget—his prerogative as Mali’s emperor—and carries a fleur-de-lis scepter, the symbol of European royalty.

Gold past and present raises many questions: What does it mean to create devotional images with the currency of international finance? Was too much gold ever deemed excessive, idolatrous, or dangerous to the function of sacred representation? How does the history of mining and the extraction of the raw material—and the environmental and labor implications of mining—nuance the meaning of each painting? We invite you to consider these and other questions as you visit the exhibition.

Africa as the land of gold captured the European imagination. In the 1320s, when Simone produced this altarpiece, Mansa Musa, the Muslim emperor of Mali, made his pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca. Observers singled out the epic journey for its magnificence, marveling at his retinue, the sheer number of enslaved people it included, and the vast tributes of gold distributed along the way (so much that it depressed market prices). For Europeans, including the royal owner of this map (at bottom right), Musa represented a new era of transcontinental trade as “the Black lord…the richest, and noblest, lord in the whole region, because of the abundance of gold obtained in his land.” He holds a gold nugget—his prerogative as Mali’s emperor—and carries a fleur-de-lis scepter, the symbol of European royalty.

Gold past and present raises many questions: What does it mean to create devotional images with the currency of international finance? Was too much gold ever deemed excessive, idolatrous, or dangerous to the function of sacred representation? How does the history of mining and the extraction of the raw material—and the environmental and labor implications of mining—nuance the meaning of each painting? We invite you to consider these and other questions as you visit the exhibition.

Metal of Honor: Gold from Simone Martini to Contemporary Art is supported by the Abrams Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Wagner Foundation, the Robert Lehman Foundation, Fredericka and Howard Stevenson, and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Additional support is provided by an endowment grant from the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Media Partner: The Boston Globe

The Museum receives operating support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, which is supported by the state of Massachusetts and the National Endowment for the Arts.